Like estate sales or cat burglary, Peter Ross’s photographs of William Burroughs’s possessions provide a glimpse into the material world of someone we thought we knew. In the interview below, Ross explains how the pictures (see here for the complete collection) explore the myth of the man through a selection of weird, touching, and often unexpected possessions found in Burroughs’s windowless New York City apartment, preserved since his death in 1997.

Photographer Peter Ross (his series on spiritualists was featured here in January 2008) lives in Brooklyn. He makes photographs, usually portraits, for designers, corporations, agencies, publishers, and for himself.

How did you end up photographing William Burroughs’s stuff?

William Burroughs lived for many years in the former locker room of an 1880s YMCA, on the Bowery in New York City. The almost windowless space was known as The Bunker. When he died in 1997, his friend and mine, John Giorno, kept the apartment intact, with many of Burroughs’s possessions sitting as they were. Part of the space is now used for Buddhist teachings, and the apartment is a wonderful mix of Buddhist wall hangings and pillows and carpets and Burroughs’ personal furniture and collections.

Is the room still intact?

His bedroom is as he left it, with all his stuff in place. Giorno looks after it, and occasionally houses visiting artists and friends and Buddhist teachers who come to teach in the main area of the space.

Did these objects go back to their home after being photographed?

I spent my day going through the room and removing items to photograph on a backdrop that was set up in the kitchen, on Burroughs’s dining table. I would then return the objects to his room.

How did you choose what articles you wanted to photograph?

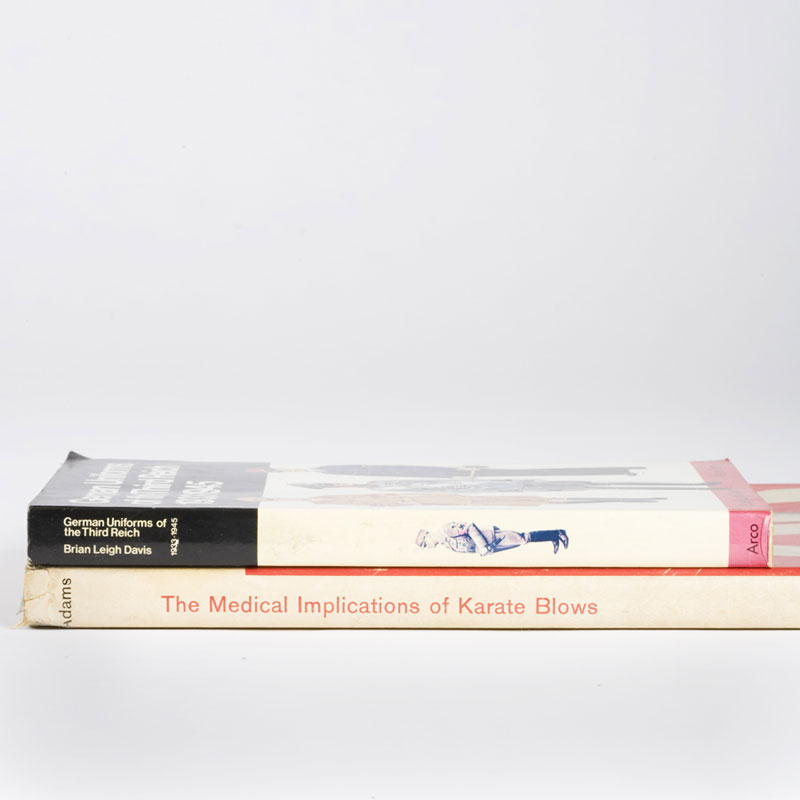

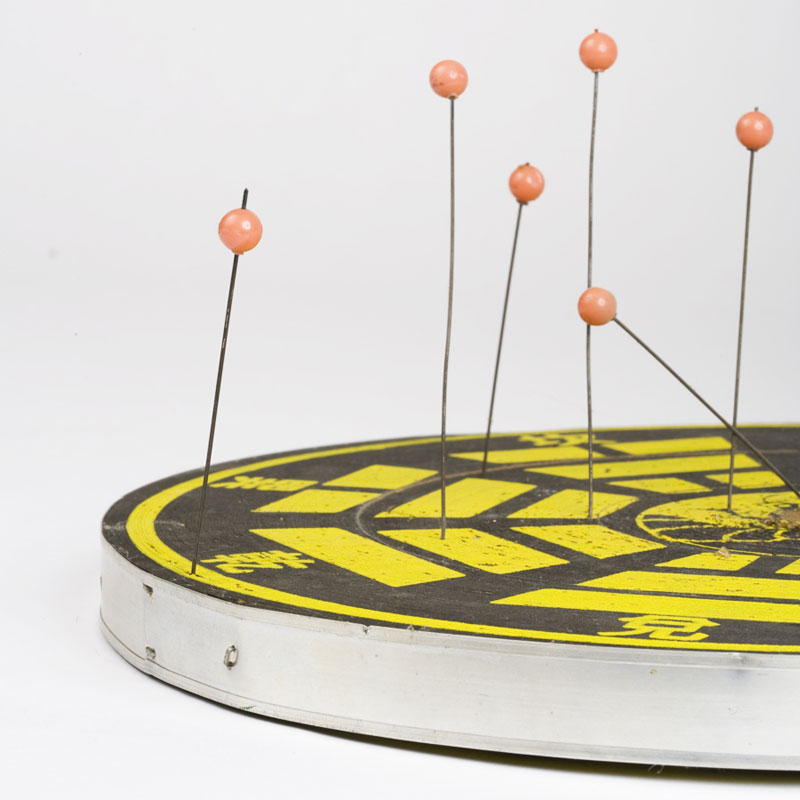

Most of the items just jumped out at me. How could I pull a book titled Medical Implications of Karate Blows out of a stack and not photograph it? Or the typewriter with his name on it? The blow darts and board that hang on the wall in his bedroom?

Well, how did you decide on the angle for each photograph—why the bottoms of the shoes, for example, instead of the tops?

I challenged myself to try and find what was unique to the items. I was looking for something historical and specific to their owner, and short of that I was pushing for an off-kilter angle or placement.

Shoes are just shoes, but only one man wore the holes into the bottoms of this pair. Just think of where these shoes have been, the conversations they have witnessed. These shoes likely have met many of my heroes of New York’s 1970s and ‘80s culture.

Was photographing each piece out of context an attempt to separate the stuff from the man? Should the pieces tell their own story?

I think it’s interesting that I know where these items sit and what those rooms look like. I know the lighting, the stillness, and the thick concrete walls, but the viewer does not. The viewer’s imagination is put into play with each image. That might not have been the case if these pictures included their physical surroundings.

I’m trying to look at these photos and separate the stuff from what I already know or think I know about Burroughs. But, blow darts, nunchucks, The Magical Art of Karate—it does seem appropriate for a man who shot his wife playing William Tell. Were you surprised? Did the nature of the things Burroughs had in his possession at the end of his life make sense to you?

I never met the man, and so I have no way of knowing what these items meant to him. Many seem representative of the ‘‘myth” of the man, and seem appropriate to the public image we all have of him. But I have no idea if he was a lover of pinwheels, a collector of old quilts, or a compulsive shoe shiner. Maybe John Giorno knows. Maybe no one does.

I have a sense that this stuff couldn’t have existed at the same time as an iPhone or even a digital camera—it seems very much from another era. Do you feel like this is just because Burroughs was old, or is there something else going on?

Well, I bet I’ll go through half a dozen iPhones in the time it would have taken Burroughs to resole those shoes. That makes me feel greedy, wasteful, and self-indulgent. Maybe I’d be better off keeping the modern world out. Maybe we all would. Let’s all just grab our nunchucks, put on our shoes and hat and walk the streets of Manhattan.

“Stuff” really is the perfect word to describe this collection. But what makes this “stuff” rather than belongings, or possessions, or effects? What does our stuff say about us, or Burroughs for that matter?

“Stuff” seems appropriately random and irreverent, although I don’t really mind what we call it. I use my grandfather’s ‘stuff’ in my daily life to eat, to keep time, to store clothes. These acts keep him with me. But to you, it’s just stuff, not memories. These items certainly tell a portrait of what interested this man, although none of us can know to what extent. Maybe I chose items that just played to his public image, the one in my head? Why didn’t I shoot his couch, or bedside lamps, or dining chairs?

If you could walk away with one item of Burroughs’s stuff, what would you take?

The shoeshine kit. My shoes are a mess.

How does the work compare to other projects you’ve done—your portraits or your photographs of brains, for example? Could it be said that these are portraits of the objects?

I’ve spent a lot of time trying to find the right balance between people’s inner and outer identities, their common peacefulness. And the anonymous decades-old brains are a shared portrait of all of us. But these items are very specific to one man, and a man with a public identity at that. His portrait has been made over and over, and it exists inside many heads: the man in the suit, in the city or the country, wearing a hat, serious, maybe holding a rifle, or talking to Mick Jagger. This is as close as I can ever get to that man.

I tried to find something unique in each object, regardless of its history or ownership or curation. I love the brittle paper of the magazines, the shapes of the various bullets, and the textures and colors of the quilt.