We spend a week driving around the perimeter of Florida, sleeping only in towns named after planets—Venus, Jupiter, Sun City. We rack up a thousand miles on our rental car and see many children along the way. None of them strikes me as attractive, and I say as much to Patti. (I add that I also found most of the wives I saw unappealing, too, but that didn’t make me like mine any less.) Patti disagrees with me, saying that she thinks most of the kids are cute in one way or another.

I wonder how she felt about their fathers?

We get a big carton from Phyllis stuffed with a dozen outfits, shoes, blankets, all destined for the Peanut. She apologizes for her largesse but says she couldn’t resist.

Our chart claims that this week the Peanut is the size of a large banana; I pick one out of the fruit bowl and we dress it in one of the new outfits. He already looks like me, though yellower.

Thanks to manipulative ads in Parenting magazine, I want to figure out how much money to put away for college. If I can figure out how much and where to sock it away, we can start now toward the $10 billion a year it will cost when the Peanut is 18.

According to the books, PL should have been able to feel the baby moving around by now, and so we start to wonder why she hasn’t. Is it still in there? Several times, Patti has sworn she can feel the Peanut’s heartbeat and I have pressed my ear against her tummy but never hear more than borborygmus as her dinner squelches through her small intestine. One morning, however, she reports a whole new feeling, a real stirring or flopping about, high in her abdomen. The Peanut is still at home.

Every time I see Patti, she is still pregnant. I think about the baby quite often, not constantly, but she is always pregnant. It’s more and more obvious too, a hard little droop. When she leans back it just looks like an ex-jock’s tough solar plexus gone to pot. She says that she can’t really suck it in and that seems scary to me, this alien thing inside her, dictating what she can and can’t do with her own body. The fact that he moves around and she can feel it spooks me, too. He has a will of his own, quite separate from his mom’s (God, that’s weird to even type out… “his mom”), a separate person inside of her. When we haven’t gotten around to eating dinner until late, he starts to move about, protesting, a mini subcutaneous tantrum, telling us to eat, both of us.

One of the books in the precariously tall stack by Patti’s bedside suggests a Pavlovian experiment, that we play a piece of music on a regular basis, a piece which the Peanut will be able to hear inside the womb. Then, after he is born, we can play the same piece and it will soothe him.

I suggest that we play the Sex Pistols or the Plasmatics or maybe a recording of a screaming fight. That way he will grow up being soothed by the sound of violence and rise above it. Maybe a tape of my former boss, Marvin, squawking at me while he eats an egg salad sandwich.

We have both been pretty irritable for the past few days. I am starting my first shoot at my new job and have terrible heartburn which has metastasized in my mind from gas to an ulcer to end-stage stomach cancer. Patti has been finishing up a project for her British client and organizing her tax stuff.

We finally get around to discussing our foul moods and Patti tells me she been terribly worried that the cramping pain in her abdomen is so localized on the right side of her abdomen because there’s some sort of tumor on her ovaries, a fear she has had for years.

Of course, I get all rational.

I point out her ovaries aren’t located there, that we have already established that the cramping is due to the stretching of ligaments suspending her uterus, that though mittleschmertz means “middle pain,” it is always on one side or the other, and that everyone reacts to these things differently, that if she had uterine cancer, she probably wouldn’t have conceived and that we would have seen the massive tumor during the sonogram. I pound her into submission with reason and hate myself for not having a better way too soothe and support her. I’m so male.

We’re seeing the doctor tomorrow morning, so this is just the typical pre-Garberian knot that we tie ourselves into each time.

At my new employee benefits meeting, I learn about the cost of health insurance, etc., then call PL and make the mistake of saying that we should probably opt for Plan B.

“What’s the difference? What is Plan B?”

“We get broader coverage as long as we agree to go to a specific group of doctors rather than any old one.”

“Uh-huh.”

“I used to have option C but I’m going to change it.”

“Why? What’s option C?”

“You have a huge deductible but lower monthly costs. I’ve always had it since I was single because I hardly ever go to the doctor. See, if I do go, it’s fairly expensive per visit but I still have cheaper coverage if something dire happens and I end up in the hospital.”

There is silence on the other end of the phone, and then I hear hard breathing.

“Why are you crying?”

“Oh, nothing.”

“Come on.”

“It’s just that, if you weren’t married to me…”

“Yes, what?”

“…You’d have more money and freedom and… Are you sure you want to be married? Don’t you wish you could avoid all this trouble and still have option C?”

“It’s a little bit late to worry about that. I’ll see you tonight.”

God.

Patti is excited to have discovered that my shirts fit her perfectly, so I guess we’ll be dressing alike through the spring. I can’t believe I have the proportions of a pregnant woman. I’ve got to get back to the gym.

Dr. Garber’s receptionist gives us a copy of the lab report from our amnio. It contains a Xerox of a fax of the map of the Peanut’s chromosomes, which will come in handy if he is ever arrested for murder or something. Patti asks if we could get an original of the map “so we can frame it.” I suppose that compared to the SATs and his driving test, the Peanut’s first passing grade on an exam is fairly significant. The receptionist, who surely must have seen it all before, acts like our request is unusual.

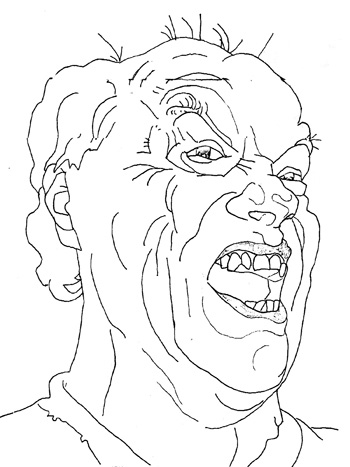

As Dr. G. reviews the results, PL asks her why there is a note that describes the sample as ‘bloody.’ Was she hemorrhaging internally or something? No, that’s a standard result when they jab a big damned needle through the placental wall. Well, what about the fact that the sample only grew 13 instead of 15 sets of chromosomes? Is he missing part of his DNA and will he come out looking like a Cro-Magnon man, dragging his knuckles along the sidewalk? No, that’s no big deal at all, all his genes are intact. Then PL asks her about her “tumor” and the doctor replies, “Nope, the ovaries won’t work. You will have to find something else to worry about.”

She really is a good and sensitive doctor; not overly protective but quick to reassure whenever we are freaking out about something. She gives us a lengthy talk about how young doctors have become overly dependent on all the technology available and how it prevents them from dealing with a patient as a whole, living person. Then she recommends Stacy Allen, a midwife (such a medieval term, like “yeoman” or “pillory”) who will teach us birthing technique. She combines two different techniques we’ve read about in our many textbooks (it will be on the final!): Bradley and Lamaze. Apparently Dr. G spent two years in Paris with Lamaze and concluded that much of it is brainwashing. She prefers Stacy’s hybrid technique.

She tells us more about what to expect when the big day arrives. At the hospital, the same nurse will stay with us, one-on-one, through a 12-hour shift and I will get to stay there overnight. (Maybe we can all get matching PJs!)

Mike Kahan is now in my gym. Jerk. A good excuse not to work out.

Everyone’s a damned expert. PL goes to the dentist (she has to have her teeth cleaned every three months because of the increased blood flow and chance of inflammation) and the hygienist tells her a bunch of horror stories including the trauma of her own very recent miscarriage. She also tells her to drink lots of tap water because it’s overflowing with fluoride that goes right into the Peanut’s teeth buds as they develop. The enzymes in his saliva will actually incorporate fluoride and he’ll never have any cavities. Then he can put hygienists out of work. Yay.

We are going to middlename our boy “Tea” because we love it so. Not your medicinal jasmine or chrysanthemum nonsense but hearty pint cups of good black English char with lashings of milk and sugar. Unfortunately, Pregnant PL has to cut back on our drug of choice. Decaffeinated tea is like mouse piss so she is going without all together. Every so often, she does break down and swills a hearty double bagger; perhaps this will turn the Peanut into some sort of freak but more likely he will just be born with the rest of the family’s addiction to the holy bush. We must start shopping for a mini teacup soon.

For the first time, I feel the Peanut’s little kick. I put my hand on Patti’s stomach and then feel a little prod as he hoofs me from within. What a little goon! Then we play a game where PL jabs her stomach and he kicks back. After three rounds or so, he seems to go to sleep. Or to have a concussion.

We moved an awful lot when I was a child. Each time our belongings would be shipped in a big crate to our next destination. Anything that wasn’t vital didn’t make the cut and so our memorabilia is down to a hardened core.

Pipsi takes us down to her storage area in the basement of her apartment building. An old battered tin trunk, originally Pakistani, holds our baby clothes. There is a tiny dress that belonged to Pipsi, sewn by her grandmother when she visited India in the 1930s, accompanied by my great-grandfather and two huge German shepherds. Pipsi gives us some of my baby clothes, a blanket, and some tiny Pakistani shoes with curled toes.

We rent a movie called The Paper, thinking it’s a comedy about journalism. Toward the end of the picture, one of the characters, who is terribly pregnant, starts to hemorrhage. As the medics roll her out the door, her husband comes home, terribly late from work. She is rushed to the hospital, chaos, questions, a dash to get her anaesthetized, blood, carnage, Caesarean, etc.

I go pale in the darkened living room and then realize Patti, too, is shaken and teary. We console each other and talk about how neverending the fear is, the dreams of disaster that seem to be the emotional price we must pay to bring a little baby safely into the world. As usual, the more disasters I foresee, the more reassured I am that none will occur. The bad things that happen to me are never the ones I’m looking out for.

So many of Patti’s clothes don’t fit. Her pantyhose cut deep incisions around her abdomen. She struggles to get into her skirts and leaves them unzipped.

She is excited to have discovered that my shirts fit her perfectly, so I guess we’ll be dressing alike through the spring. I can’t believe I have the proportions of a pregnant woman. I’ve got to get back to the gym.

Each night Patti’s lower back kills and the tendons and nerves deep in her buttocks need a good rubbing. She is crabby in the evenings sometimes (but I’m sure I am, too) and, after a couple of weeks of insomnia, is starting to snooze properly again.

She just bought a new book on nutrition and I got agitated when I realized how little food we have in the house, particularly good food. It seems very slovenly to me to have bare cupboards. What will we do when the kid shows up and we have no food? Will he just live out of bags from McDonald’s and hotdogs from the street? Oh, shut up.

I’m hanging out with a colleague when he gets a call from his mother and tells her about his wife’s horrific problems. The gist of it involves sonograms, no heartbeat, further tests, renewed attempts and other grim reminders of how dreadful reproduction can be. He is roughly the same age as I am and it hits me profoundly how lucky Patti and I have been that, so far, our tribulations are all our own invention.

That’s how so many lessons about this pregnancy come to me, sudden bursts of awakening, epiphanies that reveal joy or some profound new sense of myself or my marriage or that the fact that we are bringing a whole new human life into the world or how much fun it will finally be when the Peanut pops out.

They’re the sorts of emotions you usually only run into in Rodgers and Hammerstein numbers.

Jack. As cool as Nicholson, as tough as Palance, as adventuresome as London, as innovative as the Ripper.

We need a rocker. Not Chuck Berry, something more solid and comfortable. We decide that it would be cool to get an unfinished piece and then paint and decorate it ourselves, and so we go to a place in SoHo that specializes in raw furniture. They all suck, too rickety or uncomfortable.

I get a catalog from a company that makes Shaker furniture, classic designs in maple or oak. I could buy a kit, assemble it, weave the seat out of rushes, then sand and finish it with a dozen hand-rubbed coats of varnish.

I also consider a workshop in South Carolina—you fell a tree with an axe, then build a chair out of raw wood, all with hand tools. It takes a week of solid work.

Patti suggests we just go to the baby store and see what they have in stock. We’ll do that next weekend.

Miranda wants to host a baby shower for Patti, a surprise because Patti says she doesn’t want one. She doesn’t want to bring her friends into her pregnancy or make them feel obliged to bring us gifts. Miranda thinks she’s ridiculous and is going to throw the party at Pipsi’s house in July.

My mission, should I choose to accept it, is to break into Patti’s Filofax and cull a guest list.

I step out of the shower and Patti says, “Can you imagine that what’s in my stomach will look like that in 30 years?”

“Disappointing, isn’t it?” I reply.

Patti’s sister has sent us all her old pregnancy books. I flip through Meditations for Mothers. There are only two pages on fathers. One says new dads are very needy. The other says they feel, and are, incompetent. Meditate on that, sucker.

I’ve been trying to read The First Twelve Months of Life but the author veers back and forth from dry lab reports to patronizing pap, assuming the reader is either a clinician or a hopeless moron. Deb has recommended Touchstones by T. Berry Brazelton, which seems far more modern and sensible.

Since I have been able to feel the Peanut moving, books on the baby after it’s born seem a lot less theoretical. When I read Spock on the cruise, it was like studying a software manual without ever having seen a computer. Now I am much better at visualizing all the changes and behaviors we can expect.

I tell Patti that I can’t really imagine the baby calling me “Daddy” and that, seeing as there is such a small difference between that and what the rest of the world already calls me, perhaps we can be known as “Mommy and Danny.”

She rolls her eyes and says, “This baby better be ready for some real weirdness.”

Sometimes when the Peanut kicks, you can see a little bump in her stomach like a Jiffypop when the kernels start to plump. I am expecting to see a little fist punch out before long, separated from the world by just a layer of skin.

Our house is a fucking mess. We have stuff all over the place in piles and must get some of it out of here. I get home at seven and we plan to make some headway. A few weeks ago, PL did a bunch of research on storage places but now the growing clutter has swallowed up her list. While she looks around for it, I pick up the Yellow Pages. The only storage facilities I can find are down on Canal Street or up in the West 20s, too far away. Then I spot one just a block and a half from our apartment and we decide to check it out tomorrow.

Then Patti gets upset.

“I can’t believe I did all that work then I lost those stupid fucking notes.”

“But it’s OK. We’ve got a place now.”

“No, I did all this work and then you just pick up the Yellow Pages and find a place in just a couple of minutes.”

For the rest of the evening she remains pretty pissed and then, just before bed, she disappears into the bathroom for a solid hour. When she finally comes out, her eyes are red and it’s obvious she’s been crying. She goes off about the mess the house is in, how overwhelmed and tired she feels, how she won’t be able to look after the baby, how will she find work…

Fortunately, I keep my mouth shut and eventually all the lava pours out.

We can breathe again. We’ve rented a storage space (four feet by eight by ten—similar to my first apartment, only with a doorman) and started to move our stuff on a borrowed dolly.

We cut quite a figure as we trundle down the road, me pushing this handcart heaped high with our belongings and Patti and her big belly waddling alongside carrying her purse.

Shit out, shit in. We rent a giant Taurus and head to IKEA in New Jersey. We buy chests of drawers, rugs, shelves, glasses, and a bed for Houndy. It takes three elevator loads to get it all up to the nursery. I have to snap at Patti to stop her from lifting huge planks and boxes and then we spend the next two days and nights assembling cunning Swedish chests and cursing over missing bolts and scraped knuckles.

Dinner with Pipsi, and the ghost of my father joins us. After three and a half decades of estrangement, Pipsi and Keir have begun corresponding. She shows me a recent letter, a response to the news of the Peanut’s impending arrival. He says that he knows nothing about “the mother” (he didn’t come to our wedding) and asks if she is English. He also revealed that his father, Clifford Horace, used to call my grandmother “Jack.” Strange.

I hand the letter back and say, “That’s all very nice but I am still pretty ambivalent about Keir even knowing about the baby. Why did you tell him?”

“I think he has a right to know he’s going to be a grandfather,” she replied.

“Fine. He can know about it but I don’t think he has any sort of right to any sort of real connection to the baby. That’s what I wanted to have with him and he rejected it. It’s like he has this idea that he has some biological right, you know? He thinks that it all makes his behavior excusable no matter how cavalier he is. He can hold me at arm’s length, vanish for years, be totally self-centered and it’s all fine because nurture is irrelevant. It kills me. He has this sort of ‘I gave at the office’ thing; he contributed DNA. It’s like adoption turned on its head. A lifetime of love and care and sacrifice and teaching doesn’t mean shit compared to the fact that he once had sex with you.”

“I don’t like that kind of talk.”

“Well, it’s true. And it’s like if I acknowledge or encourage his connection to the baby, I’m just encouraging his twisted viewpoint into another generation.”

I don’t know if she gets what I’m saying. Since she reestablished contact with Keir and decided that he’s a marvelously brilliant and eccentric guy, she is quick to defend him. Secretly, I think she has some fantasy that his relationship with Sue is on the rocks and that there’s a chance that she and he could hook up again. I just find it ludicrous. In any case, we often find ourselves on opposite sides of the Keir issue.

My father had nothing to do with my life for most of it. When his own father died a few years ago, he decided to come and visit me in New York and see if I was OK. After a couple of days, he made it clear that he thought I was far too American and urban and careerist. There were no bones about it: My life was somehow wrong and I should be more like him—terribly English and cynical and misogynistic. I have always felt so rejected and so weird about it. I’ve spent maybe a total of 15 days with him since I was four and yet he feels he can judge and condemn me as he does. It’s bullshit.

Our conversation moved to a discussion of Pipsi as a mother. She said that she was so weirded out by the idea of being pregnant that she didn’t do much in the way of prenatal care or spend much time thinking about what it would be like when she had a baby. She just couldn’t believe she had gotten herself into this predicament. Only Keir’s mother, Nana (or “Jack”) was able to get her to snap out of it, to realize that not only was she pregnant but that she was soon going to have a baby and must start taking better care of herself.

She confessed that she didn’t have much in the way of a philosophy of parenting; she only knew to avoid what her parents had done, i.e. the horrors of boarding school.

I had to ask. “So why did you send me far away when I was nine?”

“Well I had too much to handle and I thought it would be a good experience for you to live in Pakistan with your grandparents. Besides, that way I could finish my thesis faster.”

“What was the rush?”

“I don’t know. In fact, when I handed it in, my adviser pointed out that I had just voided the rest of my grant. I could have put my dissertation in a drawer and lived for six months for free.”

“Great.”

“So do you think it was such a bad thing, your going to Pakistan?”

“I dunno. In some ways it was good, an important experience. It just seems a less than ideal solution to the situation. I always felt that you and Miranda and Mike Kahan developed some kind of bond during that time that always excluded me, ever after, like I wasn’t a part of the original cast somehow.”

“I don’t think I was really fully formed at that point, I was only 30.”

“I guess.”

PL asks me to switch sides of the bed with her. She is supposed to sleep on her left side so as to take the strain off her heart and as a result she is always faced away from me. I agree, and we both sleep better than we have in weeks.

Pipsi calls. She’s worried about coming to our place or dinner for fear of a “sighting” of Mike Kahan.

I’ve decided to do some sewing. When I was in college, I made myself a shirt out of some wild fabric, broad stripes of brown, orange, mustard, and red. I couldn’t figure out how to make proper buttonholes so I used Velcro to fasten the front. The first and only time I wore it, my date said, “I didn’t know you got a job at Burger King.”

This time I am making mini-overalls from a Butterick pattern and some barnyard animal fabric we bought a few weeks ago. I can handle the cutting out part fairly well and then spend the rest of the evening reading the instruction manual for the sewing machine and unjamming the bobbin. Patti, the home economics major, darts around the edge of my project like a sheepdog guiding a herd but I keep backhanding her away. If this kid is going to dress funny, I want all the blame.