The man walked with a limp and a cane and couldn’t stand quite straight. He made his way slowly, deliberately to the front row of the auditorium in the London Transport Museum, a custom-made fluorescent yellow vest over his dark blazer.

Printed on the vest were various facts and figures of the Bethnal Green Tube station disaster: 173 people killed on the stairs the night of March 3, 1943; death in all cases by asphyxiation, there were no bombs; largest civilian accident of WWII.

He’d come to hear me speak on the topic, the subject of my first novel. He sat down and looked up at me on the stage. To say his expression was skeptical would be an understatement. I am a relatively young American novelist. He is Alf Morris, one of the accident’s oldest survivors.

My first novel is labeled as and widely considered to be historical fiction, but I can honestly say I never thought of it that way, not in all the years it took me to write it.

Although it is based on a historical event, it was not until after the events of 9/11 that I began to think the accident at Bethnal Green might be something I could write a story about. I was thinking a great deal then about disasters, about communal loss, about how we attempt to publicly reckon and eventually commemorate tragedy. I was following in the press the demands for an independent investigation into 9/11, and as I wondered what would happen, I found myself pulling out my notes on Bethnal Green. It seemed to me there were parallels: A community had been deeply shocked and wanted an official investigation to tell it what had happened. Though the scale of the tragedies is different, in both instances a great deal of hope—for explanation, reform, even redemption—was placed in the inquiry and report-writing process. That is what interested me. The inspiration was always contemporary.

I find it hard to define exactly the difference between fiction and historical fiction. When is the cutoff date? Who decides? Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, published in 1951, is set during WWII but is not generally described as historical fiction. Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, published in 2006, is based on political events in 1960s Nigeria, but is referred to as historical fiction. In the simplest terms, let me say that there seem to be books about which one is compelled to use the terms “epic,” “sweeping,” “grand”—dare I say, “historical.” Let’s put The Invisible Bridge by Julie Orringer in this category, and Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall. Then there are books that are arguably “historically imagined” (a term I prefer) about which one would not necessarily use those words. Here I would put Girl With a Pearl Earring by Tracy Chevalier and almost everything by Penelope Fitzgerald, including The Beginning of Spring (my favorite).

I always wanted my novel to be in the latter category.

Here’s an analogy: movies and after-school specials. Calling a movie an after-school special seems to broadcast something lacking about it. The same thing happens when a book is described as historical fiction. Thus my dislike of the term.

During my talk at the London Transport Museum I didn’t look at Alf much. In truth, he was largely obscured from my sight by the podium, but even if he hadn’t been I would have avoided his gaze. I was in London for a week for the UK launch of my novel and I’d already endured several days of questioning about it. One radio host began the interview by asking if I’d been scared to take on the mythology of the Cockney East End. He said, “My God! It would be like me trying to write a novel about Brooklyn!”

Other interviewers asked if I’d considered writing the story as nonfiction. I was asked if I’d interviewed survivors. It was suggested several times that it was a daring move to take a true event and mix it up with fiction. Oddly, I found myself in the position of defending the very premise of historical fiction, which turns out to be one thing when you’re talking to writers, editors and other literary folk (when the “fiction” is always stressed), and quite another when you’re facing a survivor. Suddenly, the “historical” is all-important. I met a woman, Sandra Scotting, who is the secretary of the Stairway to Heaven Memorial Trust, an organization trying to raise money for a permanent memorial at the site. In 1943, Sandra’s mother held her baby nephew in the crush at Bethnal Green and didn’t know until the next day that he’d died in her arms. Sandra’s not particularly interested in the fictional parts of my novel, and who would blame her?

It seems fiction is fine unless a subject is raw—then we think nonfiction is required.

Often I found myself explaining that there was a foundation of truth upon which my novel was built. I gestured with my hands: firm, smooth motions to show the foundation; little swirling, twirly circles to suggest the fictional aspects. And yet time and again, these words and ridiculous gestures reassured my questioners, while inside I cringed, knowing my book was actually about how impossible it is to ever establish the absolute truth of any tragedy. In one interview, I was asked how I felt about my book becoming the definitive account of the accident, and I actually blurted out, “Oh, but I hope it won’t!”

On March 3, 2011—the 68th anniversary of the tragedy at Bethnal Green—I attended a commemorative service held in a church across the street from the site of the crush. The ceremony included a few hymns, a brief homily, an update on the work of the Stairway to Heaven Memorial Trust, the Lord’s Prayer. At the end, the names and ages of the victims were read out one by one. It was extremely moving, and whether it was all the questioning I had endured that week or the fact that I hadn’t slept well for days, I felt weak with doubt. What was I doing there? If I’d attended this service while I was trying to write the book, I’m certain I would have lost confidence. I had made the story mine while writing, but the people filling that church had had their lives changed by it, and the chasm between us never felt greater.

As the crowd filed out in a procession to lay flowers at the entrance of the station, I stayed back on the steps of the church and watched.

Two weeks after returning from London, I attended another tragedy’s commemoration: the 100th anniversary of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. This fire, which occurred on March 25, 1911, claimed the lives of 146 people and is credited with changing America. It inspired more legislation—fair labor laws, better building codes—than any other accident in U.S. history. Many books have been written about it, and it has been publicly commemorated for years.

And yet: A large display of flowers was nearly misdelivered over confusion about the correct address of the building, even though there was already a growing pile of bouquets in the right spot. A man in the crowd asked where the fire had occurred and someone pointed confidently to the wrong building; a few bystanders thanked him and nodded, while a few others remained silent, their expressions revealing they didn’t think much of the misinformation: purple and black bunting marked the correct building across the street. Members of Local 79 had made signs with the names and ages of the fire’s victims, and this was a moving sight: big, strapping construction workers holding signs with young girls’ names:

Annie

Miller

16

Sonia

Wisotsky

17

But it was a cold day and as the ceremony wore on, some of the union workers left. As they did, they handed their signs to other people in the crowd. I got one. It said:

Beckie

Reines

18

The man who handed it to me explained, “These two people were both 18 when they died in the fire.”

I checked later, just to be sure. Beckie Reines was one person.

A New York Fire Department truck sat idling on Greene Street for much of the ceremony, a 9/11 memorial emblem on its door. To see the giant screen broadcasting the day’s events, I had to look over the truck, a hook and ladder that lost 9 people on 9/11, the names listed right there on the truck’s side door. I wondered about Sept. 11, 2101, and the commemoration that will likely take place that day. In a hundred years—or, frankly, this coming September, when it’s the 10-year anniversary—will someone say 9/11 was a conspiracy job, or the work of a Jewish cabal, while a portion of the surrounding crowd listens and nods?

Near me was a woman who was the author of a book about the Triangle Shirtwaist fire. She was pressed into the front row of the general viewing area, right up against the barrier, her book under her arm. She’d arrived early and was the first to notice a couple of elderly people—wearing pins on their coats showing a picture of the ancestor lost in the fire—who should have been in the VIP seating. She immediately mobilized a small portion of the crowd, called over a police officer, and before long we’d opened the barrier and let them through. She kept shaking her head and saying, “I know. I know. I wrote a book about it.”

I guess I’m missing the gene others seem to have that makes them worry, when they read a novel, about what is true.

I never asked whether her book was fiction or nonfiction. I did notice, however, that while the ceremony that day included song, narrative poetry, and many fact-heavy speeches, it did not include any fiction. Neither did the service at Bethnal Green. Why is that? What is it about nonfiction that makes it right for a rally, while fiction feels more appropriate for private contemplation?

It seems fiction is fine unless a subject is raw—then we think nonfiction is required. We want facts. In his prefatory note to A Quiet American, Graham Greene wrote, “This is a story, not a piece of history.” It’s fascinating he felt he had to say that. As long as nothing appears to be outlandishly wrong—and often a decent author’s note reveals the research and intentions behind the book—I am happy to believe the story I’m reading might have been. Compare Dave Egger’s Zeitoun and Tom Piazza’s City of Refuge. Both books are about Hurricane Katrina, one nonfiction, the other fiction, both positively bursting with truth. Which you read depends on your preference as a reader, but one is no less true than the other.

The other day the writer Tayari Jones said on NPR, “When it comes to memoir, we want to catch the author in a lie. When we read fiction, we want to catch the author telling the truth.” I guess I’m missing the gene others seem to have that makes them worry, when they read a novel, about what is true. I am the kind of reader more likely to pick up Katharine Weber’s Triangle than Triangle: The Fire That Changed America by Dave Von Drehle, and after I read it I would understand that I’d learned something about the tragedy and how it changed lives. If I wanted to know more history, I might turn to nonfiction first, but what nonfiction account can truly claim no bias, no author’s hand?

The day of the Triangle fire commemoration, there was a loud-talking man who seemed to feel the crowd was gathered for his benefit. He talked so much I don’t see how he could have heard much of the rally, but what he did hear—a bit of a poem that told the story of the elevator man who went up again and again to save a total of 150 workers—inflamed him and he dismissed it as “the NPR treatment kind of crap. A marionette performance set to music. Yeah, I need that like I need a case of jock itch.” I doubt he’s going to read a novel about the fire. But others stood solemnly, listening to the poem, and I think that, like me, they were thinking about the bravery required to take an elevator up 18, 19 times to a burning floor in a tall building. Those are the novel readers.

At the conclusion of my talk at the London Transport Museum, Alf Morris stood up. There was to be a question-and-answer period but he raised his hand, stood up, and before anyone officially called on him, he began to tell his story. On the night of March 3, 1943, Alf was a 12-year-old boy playing with his cousin in Bethnal Green. They ran to the shelter when the alert sounded and were in the crush on the stairs. His cousin died; Alf survived because a warden was able to pull him out by his hair. Mistaking my grimace for a smile, Alf said, “I can assure you it is no laughing matter, young lady.”

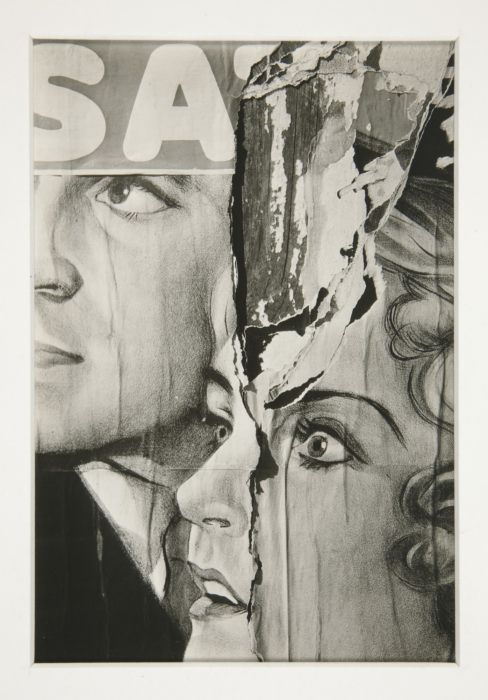

He’d come with facts and figures on his vest, in his head, and in his hand. He held up a map that proved, he said, the authorities were hiding another entrance that could have been used and might have prevented the disaster. “I don’t know about your story,” he said, gesturing at the blown-up cover of my book on the screen behind me, “but when you think of the people, all those people who died…” He lowered and shook his head. His point was loud and clear. A story doesn’t bring a single one of them back. But as Alf talked, his tone a bit argumentative, expressing his opinion about the causes of the disaster, he illustrated my point too. Tragedies are full of stories. Every version is different.

At its best, fiction helps us understand how we feel about the facts we think we know—the facts we think we’ll never forget, but do. “Fiction must stick to facts,” Virginia Woolf wrote, “and the truer the facts the better the fiction.” In the lobby after the event, Alf’s wife bought a copy of my book, and Alf shook my hand. He thanked me for my donation to the fund for the permanent memorial. I wanted to say more to him, but couldn’t find the words. He walked away and I signed a book for the next person in line.

I tried, I could have said. I tried to understand what this tragedy did to your life.