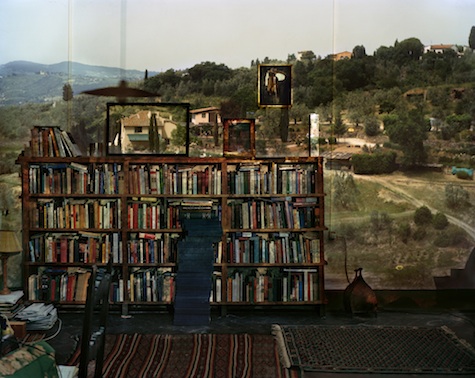

in Room With Bookcase, 2009, courtesy Abelardo Morell

When I recently moved to New York to live with my partner, Dustin, I introduced 22 boxes of books to the one-bedroom railroad apartment in New York’s Hell’s Kitchen, where he’s lived for 19 years. Dustin built over 70 feet of bookshelves for me and in just one day I filled them, feeling, afterward, mixed pride and shame at the size of my collection. Which still didn’t quite fit on the shelves.

Dustin built one more shelf. And another. I filled these also. Now all of the books are off the floor and out of boxes, and the shelves he built fit beautifully into the room. The books do not overwhelm, but this is because they are all on shelves. There’s really no extra space, which is to say, any new books mean that soon the books may overwhelm us. Three, or perhaps 10 new books, much less the 30 I can easily acquire per season, could take us into crisis.

My books have moved with me from Maine to Connecticut to San Francisco to New York, to Iowa to New York to Los Angeles to Rochester to Amherst and now to New York once again. I’m a writer, also the child of two people who were each the ones in their family to leave and move far away, and the result is a life where I’ve moved regularly, and paid to ship most of my books so often I’m sure I’ve essentially repurchased them several times over. Each time I move, my books have grown in number. Collectively, they’re the autobiography of my reading life. Each time I pack and unpack them, I see The Phoenicians, a picture history book my father gave me as a child, and will never sell; the collection of Gordon Merrick paperbacks I shoplifted when I was a closeted teenager, stealing books no one would ever let me buy. The pages still retain the heat of that need, as does my copy of Joy Williams’s Breaking and Entering, bought when I was a star-struck college student at the Bennington Summer Writers’ Workshop 20 years ago. Each time they were all necessary, all differently necessary.

In the life of a New Yorker, a new book is a crisis the exact size of one new book. I spent three hours scrutinizing the shelves for weak links that could go to the used bookstore, projecting either into the past—When had I read this book and why?—or the future—Would I ever read this again, or even read it?—and filled three bags. I held my two mass-market paperback editions of Joan Didion’s Play It As It Lays, bought at Church Street Books in San Francisco in 1990—one to own and one to lend—and after all this time, put the second into the bag. The one remaining now a reminder that I once had two.

It’s time, I told myself on the subway uptown afterward, to consider the e-book.

I had resisted. Partly for the obvious reason: I love books. I remember how it felt when I found copies of Derek Jarman’s Dancing Ledge and David Wojnarowicz’s Memories That Smell Like Gasoline and Close to the Knives on Dustin’s shelves in the first days of our courtship. We never discussed whether it was OK for us to have doubles of those because we know better than to ask each other about it. A lover’s e-reader just doesn’t give off the same feeling of secrets and possible belonging in the way a bookshelf can. E-books will never be rare books or limited editions. It just isn’t the point of an e-book.

The device I’d been using to check for news now had something inside of it that helped me make sense of the news for myself, the apparently killer app called “the novel.”I wrote back in 2007 that I felt the Kindle needed to be sexier to succeed, and in the intervening years some of what I’ve asked for has come to pass. It no longer looks like an intercom from the ’80s, for example—this strikes me as a big improvement—and the price has steadily come down. But after taking my books to the store, I still didn’t feel ready to get one, either. I did, though, feel the responsible way to face my book problem was to at least begin with the Kindle app on my phone. If I could use my phone to obsessively check for news updates every hour, I could at least try to read a book on it. I downloaded the app with the lowest of expectations, and as I perused the store, decided to begin with 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, something I’d never read before, and that was also free on the Kindle—thus, an easy test.

I opened it on my next subway ride downtown. It began with approximately two paragraphs of the book, lit up on the screen of my phone. I tapped the side of the screen and it flew to the next three paragraphs, and so on. A few minutes passed and I observed that I was reading peacefully. It was both an entirely new reading experience, like I had a secret that fit inside the palm of my hand, but it was also familiar: In the fifth grade I was taught to speed-read on a machine that projected sentences onto a wall at high speeds, sentences in the white box of a screen, flashing in a dark room.

Moments later, I got off the train. That went well, I decided, and slid my phone back into my pocket. And then I drew it back out, turned the app on, and kept reading as I walked, something I taught myself to do as a child when I lacked the patience to put a book down in order to walk to school.

Nicholas Carr’s book, The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains, made a big splash this year, presenting an elegant argument about the way we’re being disarrayed. The problems are structural, he argues: This is our brain; this is our brain on the internet. One favorite quote: “Once I was a scuba diver in a sea of words. Now I zip along the surface like a guy on a Jet Ski.” Yes, I thought. Me too.

When his book appeared, I’d more or less accepted that this had also somehow happened to me, my brain remapped by the internet. But now with my phone-sized e-reader that sometimes took calls, now that I was walking and reading again the way I did as a child, reading fiction, not news, I noticed during the Gulf oil spill I no longer cared quite as much about the latest shitty thing happening in American politics that was out of my control (and that also made me feel paralyzed by it). Instead, there I was on the train, reading about a giant glowing non-gasoline-burning submarine and wondering why the scientists who borrowed inspiration from science fiction never thought of using that as a tech model.

This, of course, is what fiction is for. The device I’d been using to obsessively check for news updates now had something inside of it that helped me make sense of the news for myself, the apparently killer app called “the novel.” But it also made me question whether the internet had really been the problem.

I was someone who either couldn’t send a letter at all, or would exchange enormous illustrated manila envelopes full of letters, photos, and personal zines.One part of those low expectations, one part of that shame in the “mixed pride and shame” from earlier, was that as I unpacked, I noted how many books I hadn’t read. I had low expectations for reading on my phone partly because I had low expectations for myself, having moved with many unread new books. These were not like the stories from my past on my shelves, and with each day they became more like half-remembered might-have-beens, like those old phone numbers I used to find in my wallet when I was single. I was never going to call them and could no longer remember why I even would.

Part of the blame fell, ironically, on a life of writing and teaching writing, where I spent hours in front of sentences every day. Like any academic, I had the reading I needed to do for my research, the reading to prepare for class, the reading and the editing of student writing. Reading for pleasure seemed too much like going back to work. But of course, there was also the internet.

There was no sign in my first experiences that it would become a problem. I used my first email address during my last semester at grad school in 1994 to send just one email to a friend that said, “What do I do with this?” This friend was Choire Sicha, who went from editing Gawker to co-founding The Awl. We knew nothing then of what would come, is the thing, and I don’t think we would have believed you either, if there was a way for you to have told us back then. I was someone who either couldn’t send a letter at all, or would exchange enormous illustrated manila envelopes full of letters, photos, and personal zines. It may be we wanted blogs back then but didn’t know how to say so.

At that point, my computer was something I used only to write—a typewriter with a big electric sheet of paper called a screen, the size of a large paragraph and lit by glowing green letters. By 1996, I had AOL, email, chat rooms. By 2000 I had a color screen. In 2001 discovered I could throw the I Ching or have my Tarot cards read online, I had an author site made for my first book, and I was shopping on the web. Spring of 2002 was when I discovered most, if not all, magazine editors/literary agents/publishers wanted submissions handled electronically. In 2003 I got an Xbox with the online subscription, and in 2004 I began blogging and going on dates found on the internet. I gave up AOL and became a Gmail user. In 2005 I watched my first television show on iTunes, in 2006, I joined Facebook, and in 2007, Twitter. 2008 began with an invitation for me to be a Hulu beta tester.

By 2010, my typewriter with the electric sheet of paper was gone, a quaint, barely remembered thing. My computer was now a door to something chthonic, a screen that allowed me not just to write, but to send and receive mail, watch TV, movies and porn, get omens about my future, shop, make new friends, keep up with old ones, find love and sex—it was no longer just a writing instrument by any stretch of the imagination. And this was a disaster. But honestly, it was nothing like the disaster next door, which is to say, the decline in my reading for pleasure. None of this compared to the intensity of what I think of as my vigil.

I could call it an internet addiction, but I’d be skipping the part of it that began in 1999, when I went from feeling like I lived in a country with a marginal but vocal fundamentalist Christian community to feeling like my country had become an open-air mega-church that I’d accidentally wandered into. I remember, in 2005, swearing at the television in my mother’s house on a visit home, when Diane Sawyer, on Good Morning America, announced she wanted to talk about “faith.” It felt like Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale was coming true, the country I thought I lived in replaced by a place I’d never want as my home.

If you were to ask me what I thought I was doing in checking news sites on the internet as many as eight to 10 times per day, starting with the election in 2004, I would tell you I thought I was keeping myself safe. Especially late at night, I felt like I was on night watch for the forces that would eventually put George Bush back in power one more time. It felt like a vigil.

I’d always read the news as a part of my writing ritual: wake up, go to the newsstand, buy the Times, the Post, the Daily News, get coffee and a bagel, sit down with the papers, read until an un-definable click occurred and I started writing. But a newspaper in your hand is a quiet thing, even when it’s a tabloid. When I gradually switched over to getting my news on the web, it was like walking into Internet Fight Club, with articles headlined to incite arguments from anonymous commenters who left thousands of angry, misspelled, and misinformed comments for others, also leaving the same, and each side returning to leave more, driving traffic. Reading the Times/Post/Daily News no longer elicited the click. Now, reading it online, it was the readerly equivalent of listening to cats on meth.

“You’ve just confirmed for me the value of the pen and paper,” my editor said drily, and I laughed nervously as I retapped my notes.I would get my coffee, go online to read news instead of buying my papers, and two hours later still be clicking through and not clicking in in that way from before. There was something I both wanted to think about and didn’t want to think about, and it appeared on the glowing screen in the form of an argument, the terms of which were unresolved, and would never be resolved, and will go on until all of us collectively realize what we lose by even having it—this argument being the intensely divided politics of our age, which pose as participation, and are just a pickpocket’s ruse.

I wasn’t distracted, not exactly. It wasn’t the same as not being able to pay attention. It was about too much attention, about not feeling safe if I looked away. I was like the patient who, when the pain meds wear off, slams the button until the morphine kicks in again. I was reading the news and when it was too painful, going to look at anything else—affluence, gossip, porn, horoscopes, status updates—trying to figure out what was happening, was there a way to stop it, or a way to feel hope, or even just to feel, and with each click I believed I increased my chance of seeing the way out by reading more and more. But the more I saw, the more I was lost, and the way out was not there.

In the end, Susan Sontag’s essay “The Novelist and Moral Reasoning,” published shortly after her death, described my problem more than Carr’s book did:

By presenting us with a limitless number of nonstopped stories, the narratives that the media relate—the consumption of which has so dramatically cut into the time the educated public once devoted to reading—offer a lesson in amorality and detachment that is antithetical to the one embodied by the enterprise of the novel.

In storytelling as practiced by the novelist, there is always—as I have argued—an ethical component. This ethical component is not the truth, as opposed to the falsity of the chronicle. It is the model of completeness, of felt intensity, of enlightenment supplied by the story, and its resolution—which is the opposite of the model of obtuseness, of non-understanding, of passive dismay, and the consequent numbing of feeling, offered by our media-disseminated glut of unending stories…. (“Time exists in order that it doesn’t happen all at once … space exists so that it doesn’t all happen to you.”)

To tell a story is to say: this is the important story. It is to reduce the spread and simultaneity of everything to something linear, a path.

To be a moral human being is to pay, be obliged to pay, certain kinds of attention.

With all my news reading, I thought I was being a moral person. Instead it made me something of the opposite. It makes sense to me then that the way out was accidental. Even a little ridiculous.

Shortly after the move, Dustin and I left for a week in Maine with my extended family—each year, my brother, sister, their spouses and kids, and my mom and my stepdad all converge for one week in the summer. My family is pretty wired, and the number of smart phones and computers grows each year. The summers previous saw the innovation of putting the kids in front of DVDs and iPhones to play videos or watch games. This year my brother unpacked four iPads, one for him, his wife, and for each of his kids, and I observed how they used them to watch videos, shop online, read email, and check blogs on the porch of our island house as the sun set and the fireflies came out.

Like many, I’d been curious about the iPad, but also skeptical. It seemed entirely impractical to use for work, but I quickly saw that was the point: I could use it for play. I could get all of the activities I needed to get off my computer, and turn it back into my writing instrument. If I could read magazines on the iPad, I could reduce the amount of print in our apartment as well. When we returned to New York, I received a check I didn’t expect and watched myself go to the Apple store and buy it.

Much of what I love about books, and about the novel in particular, exists no matter the format.For a time, the iPad made everything worse. It was too easy to check social media, for example. When Dustin began feeling like an internet widow as I walked through the apartment, silently moving from device to device, we set rules on usage, which included talking to him again. The iPad then quickly disappointed: A visit to Hulu asked me to pay for something I could watch for free on my computer. My current print magazine subscriptions did not transfer to the iPad—I would have to either repurchase my magazines, an unpleasant idea, or switch to the iPad-only version, and at only a slight discount compared to the print-subscription rate. Meanwhile, my subscriptions to Granta, Harper’s, and The New Yorker, for example, provided me with online access to their archives through my computer in a way the apps, for now, can’t. The Huffington Post app was a relief—no comments!—and then an update provided the angry squadrons I’d been happy to avoid. One afternoon, I even tried to use the iPad for work, and the result was a sad gaffe in my editor’s office when I erased notes I’d been taking during our meeting with a single accidental swipe of an “undo” button I didn’t know was there. And there was no “undo” for the undo button.

“You’ve just confirmed for me the value of the pen and paper,” she said drily, and I laughed nervously as I retapped my notes.

The e-book was a reason, meanwhile, for buying an iPad—with an iPad, I could use iBooks, the Kindle app, or the Nook app, offering more choice than a dedicated reader. Also, the iPad’s color screen mattered, not just for reading magazines but for comics, too. While I hoped to save even more space in the apartment, reading them this way just happened to be amazing, like reading comics on a light board with pages that moved frame to frame and could never wrinkle or bleed. But I still hadn’t bought one e-book. After a two-week digital comics binge, I finally downloaded and opened the Kindle and Nook apps. I purchased Justin Cronin’s The Passage, a page-turner perfectly suited to the e-reader’s rapid page sweeps. By the end of the book, I was used to reading this way, and I’d put off, for one more day, the crisis of adding even one more book to the apartment. When I immediately downloaded Jennifer Egan’s A Visit From the Goon Squad next, I didn’t just enjoy reading it, but also saw it as a win. There have been unexpected domestic discoveries: The iPad is perfect for reading at night next to someone who’s asleep, both the book and the flashlight I hid under my covers as a kid. When I need to get water or go to the bathroom, I can use it to see where I’m going in the dark and not wake Dustin by turning on a light. I’m still prone to creating the need for a new bookshelf, with a recent purchase of eight physical books in a single store visit, but I’ve also put 12 books into what Dustin and I now call “the devices.” We both see this as a victory.

Many ponderables remain regarding the e-book. At a personal level, I am someone who has read books in poor light for decades without hurting my vision (despite what my mother claimed), and I’m keeping, well, an eye on that—the iPad gives me headaches in ways reading on paper never did. As a writer and former bookseller, I understand the e-book’s imperfections and limits, and monitor the arguments that it will end publishing or save it, and potentially kill bookstores, which would kill something in me, if it were to happen. But I also believe that the book as we know it was only a delivery system, and that much of what I love about books, and about the novel in particular, exists no matter the format. I’ve lately been against what I see as the useless, overly expensive hardcover, and I admit I enjoy the e-book pricing over hardcover pricing. Still, I’ll never replace the books on those shelves, and there’ll always be books I want only as books, not as e-books, like the new Chris Ware, for example, which would be pointless on an e-reader. This really is just a way for me to have more.

A month ago I picked up the iPad and found underneath a copy of Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, by Rebecca West. I’d stolen it from my brother years ago and it was one those books I’d never read, a giant Penguin paperback with pages soft and feathery from age and use. For years, I liked to hold it and flip the pages like a deck of cards and put it back down. It’s 1,158 pages long, beginning, as I discovered that day, with West resting in a hospital after surgery in 1934 and being shocked by the news of the murder of the king of Yugoslavia in Marseilles. I kept reading into her record of the way this news drove her to go to Yugoslavia, the subject of the book. I recognized West’s crisis, too—an early 20th-century version of my own. When I paused to make coffee, I admitted to myself I had finally started reading the book. But also, I was reading again in the way I’d always known, previous to the internet, previous to the vigil. I wanted to cheer a little but I also didn’t want to disturb it either, and so instead I kept reading, which was perhaps the only right way to celebrate this. If I had in fact remapped my brain with my e-reader, which I suspected, the map I’d found had led me back here.

The world remains beautiful and terrible at the same time, and either way, I know it doesn’t care what I think or feel about it. There are things to do to help others, and there are things that may never change. But if I learned anything from all of this, it’s my first, oldest lesson as a reader: There is always going to be a book that saves you. There is also a new lesson: You do not know how it will get to you.