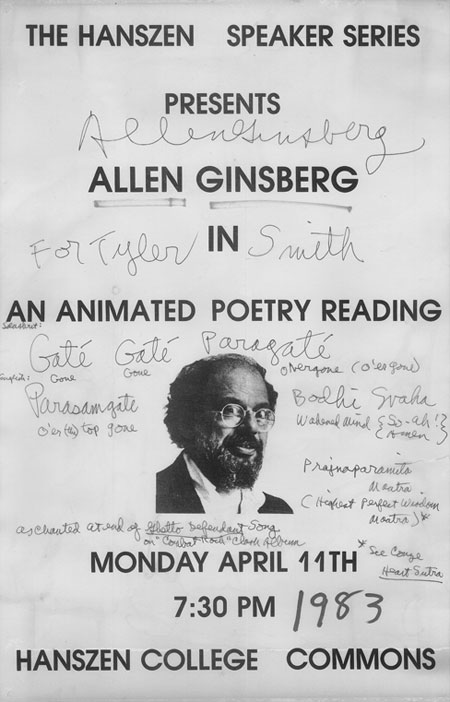

I was nine years old in 1983, when my father, a professor at Rice University, invited Allen Ginsberg to Houston to give a poetry reading with the promise of financial assistance from the dean of humanities. Ginsberg asked for a $300 honorarium and economy airfare, which must still rank as one of the greatest entertainment bargains of the modern era.

I wasn’t along for the raucous trek to the airport to extract Ginsberg. Initially, my father insisted the welcoming committee be a “class operation”—just he and the dean of humanities—but word of the poet’s itinerary got out amongst the students. (We lived on the Rice campus, my parents serving as “masters” to one of the residential colleges. From what I could tell, masters were responsible for talking down drug-addled students and assuring them their parents would not disinherit them if they switched majors from mechanical engineering to French.)

“Goddamnit, you’re going to get the boy high!” roared my mother, as throngs of Beat poetry enthusiasts, adjunct professors, incapacitated English majors, and sundry other ne’er-do-wells spilled into our house.

“Richard, get this merry band of walking felonies out of our living room and into some kind of van, please!” My father did his best to herd the felons toward the curb.

I asked my mother what the big deal was. After all, we’d had a few dignitaries in our house. The world-renowned and often-nude China expert Joseph Needham (see Simon Winchester’s The Man Who Loved China) stopped in for some video games and a lecture. James Dickey oozed onto a dais, began to read the emcee’s introductory comments, raised an eyebrow, and danced a mazurka into the proctor’s wife. We’d had our share of eminence, but this, my mother’s nervousness told me, was different.

Hours later, my father led the dean and Ginsberg—minus the throngs of deviants—through the front door. All three appeared worn. There were brief introductions between Ginsberg, my mother, and me. He shook my hand. I liked to squeeze as hard as I could to show I was strong when I handshook. Ginsberg played along until he pretended I’d hurt him.

“Oooh, macho. A vise-like grip.” The first thing I remember about Ginsberg is that he didn’t talk like people I knew, like people from Texas.

“Tippecanoe and Tyler, too,” he said, referring to my name, “Have you heard that one, little one, little man?”

“Yes,” I said. “My dentist says it to me every time I’m there. He has hairy arms and smells like smoke.”

“Bad medicine,” said Ginsberg. I noticed there was food in his beard.

Ginsberg said he knew Silverstein, said the man was “fucking crazy…maybe don’t tell your mom and pops I said that word.”

By traditional standards, or at least those of a nine-year-old boy, Ginsberg was ugly. But it was a serene homeliness, like a gentle troll, or Yoda, but with bigger ears. His hair was inherently wild, and it became even more so as he raked his stubby fingers through it in perpetual agitation. He was also a prodigious sweater and pushed his glasses back up his slippery nose every few seconds, only to have them succumb to grease and gravity as soon as he made the adjustment.

Sitting in the living room, Ginsberg and I bonded over our mutual love for The Clash, although my primary attraction to the band was the army fatigues the members wore in the “Rock the Casbah” video. I put on a fashion show for Ginsberg, in which I played Combat Rock out of my ghetto blaster, dressed in fatigues from an Army surplus store-cum-saloon in Galveston. My prized possession of the moment was an old plastic Kalashnikov that made a machine gun-like rata-tat-ratatat-ratata and while I paraded around in front of Ginsberg, I fired my gun into him, which he seemed to enjoy, indulging me with spot-on death rattles and war cries. I was even more thrilled to learn Ginsberg had been enlisted by The Clash to chant the Heart Sutra on “Ghetto Defendant.” Before my bedtime he read to me from Shel Silverstein’s Where the Sidewalk Ends. Our favorite poem was “Captain Hook.” He said he knew Silverstein, said the man was “fucking crazy…maybe don’t tell your mom and pops I said that word.”

“It’s OK. They say ‘fucking’ all the time.”

“Beautiful.”

The following night, after Ginsberg’s poetry reading (why would I want to go to that?) a group of students eager for him to impart morsels of omniscience were forced to wait outside my room while we played video games on my Atari 2600—I destroyed Ginsberg at Frogger, but he eviscerated me on Combat. In a lame attempt at armistice he explained something about angles of trajectory and mathematics, but I went supervoid. He said he’d never played Combat before, but nobody is above suspicion.

Of course, it wasn’t all Atari, Shel Silverstein, and The Clash. After the third day, Ginsberg’s residence in our home took on a quotidian routine. My mother, Ginsberg, and I would wake up early in the morning and sit around the dining room table, eating Cheerios.

“I’m sorry we don’t have better cereal, Allen,” I said. “I always ask for Cocoa Puffs. My mom and dad never get it for me.”

“Well, there’s always the teeth to think about. Lisa, pass me the sugar if you would.” My mom passed the sugar and Ginsberg went back to some stack of papers, Mom went back to the crossword, and I back to my Boy’s Life. Ginsberg was especially moved when I read aloud the account of “Scouts in Action” in which some kid fell out of a motorboat, was caught up in the rotors, then somehow rescued by a Boy Scout using his Boy Scout skills, which included a bandanna.

“Yeowch! Thank God for the Boy Scouts, eh? Tyler, you’re a Boy Scout?”

“No, I was a Webelo.”

“Huh?”

“It’s before Boy Scouts. But I got kicked out.”

“Bastards,” said Ginsberg. “Why?”

“I hit Jason Yost at the Scout Jamboree because he said my mom’s garlic bread tasted like fart bread.” I noticed my mother smile.

“You don’t do that, man,” said Ginsberg, shaking his head. In retrospect, I like to consider that Ginsberg meant that you don’t call somebody’s mom’s garlic bread fart bread, ever, but it does occur to me that he may have meant you don’t punch people. But, for most of the day, Ginsberg went off doing things with my father and a knot of giddy academics and hangers-on. I went about my business, eager for Ginsberg’s return.

However, the final morning of his visit, trouble came to paradise. Ginsberg asked my father and me to join him in yoga and meditation. Ginsberg took his Hinduism very seriously, and in our living room gave us a short but impassioned lecture about the importance of yoga as we began the process.

Before Ginsberg could utter the opening lines of his mantra, and assume the proper meditative posture, my father and I began to chortle uncontrollably. Our guru was not at all amused, and promptly stormed out of the living room, leaving us on the floor in hysterics.

My father assured me that we’d be forgiven—a true sign of yogi-like compassion from our resident Beat poet. But it was not to be. My father suggested I go and apologize, which I did, at which point Ginsberg grimaced, urinated on himself, clutched his hand around my shoulder with violent force, and fell to his knees.

An almost imperceptible snort by my father (or was it me?) and that was all it took. Blasphemous paroxysms of laughter echoed throughout the Toyota Carina.

As it turned out, he was in the process of passing an enormous kidney stone. Nine-year-olds know nothing of kidney stones, so I ran up to my room, leaving Ginsberg in an awkward heap on our kitchen floor. I felt a tangle of emotions: betrayal, guilt, a sense that I’d blown it with this cool, hideous man, at whose feet all the world seemed to kowtow. I was crushed. Mad at myself for not taking things a little more seriously.

A battery of physicians arrived at our front door and attended to him on my trundle bed. Ginsberg convalesced quite quickly and by that afternoon was well enough to shout on the phone to someone in Mexico about a grapefruit and a KrazyStraw. Later that evening, it was time to drop our poet off at the airport. Ginsberg remained silent nearly the whole ride until, perhaps as a last-ditch effort to put the cosmos in order, suggested gruffly that my father and I accompany him in a mantra. He began:

Gate Gate,

P?ragate P?rasamgate,

Bodhi Sv?h?!

We nearly made it. An almost imperceptible snort by my father (or was it me?) and that was all it took. It was over. Blasphemous paroxysms of laughter echoed throughout the Toyota Carina as my father and I chanted our own unfortunate mantra: “We’re soooo sorry.” Disgusted, Ginsberg alighted himself from the family car, muttering, “You have a lot to learn about the perfection of wisdom, both of you,” grabbed his bag, and disappeared through the revolving doors of Houston Intercontinental Airport. I never wanted to feel the way I felt right then ever again: A witness to my own guts, crippling my dimensions like a constrictor…all for what? For a pinch of juvenile folly thrown into the grinder of boys.

I felt the way I felt right then again, 25 years later, as I waited outside an Austin yoga studio in the scorching heat of my girlfriend Mary’s Honda Civic with the windows up—a penance paid in my own private Nakara. A vision of Ginsberg appears before me. “You have a lot to learn about the perfection of wisdom,” he mutters again, exhausted. There are Cheerios in his beard.

Since the Ginsberg incident, I’ve grown up enough to be philosophical about things. I’ve been to college, I’ve read Ginsberg, I’ve had the luxury of perspective. This luxury often serves as an egress, an escape from both physical and metaphysical functions I know I just can’t handle. But sometimes you can’t just be philosophical about things. You have to do them.

I am petrified of yoga. Everybody’s of course gone bananas for it, but it takes me out of my comfort zone. When I think of yoga, all I can think of is disappointing Allen F’ing Ginsberg. Then I think it won’t be long before I’m the one passing kidney stones and urinating on children and all they’ll be able to write about is that they were peed on by a guy who wrote about being peed on by Allen Ginsberg—it’s too many degrees of separation to make a dent, poor kids. Confront the fear.

Before I agreed to tag along at Mary’s yoga class, I felt obliged to explain to her a few things she already knew: a) I am inflexible and cramp easily and b) what happened with Ginsberg.

I calmed my nerves before the class by doing some warm-up mental exercises—taking two Xanax.

Nevertheless, Mary was excited. “You’ll kill two birds with one stone. The yoga will take care of your creaky bones and you’ll exorcise the dharma demons.”

“What’s the difference between dharma and karma?” I ask, deflecting Mary’s valuable and inspirational advice.

“Dharma is inherent,” Mary explains. “Everybody has some degree of it, like HPV. Karma’s what you do about it. That’s the complete idiot’s guide version, anyway.” I am only marginally assuaged by the fact that “The Complete Idiot’s Guide” is a copyrighted expression. I don’t like confronting the fear. I thought I was supposed to Howl, baby. I try.

I calmed my nerves before the class by doing some warm-up mental exercises—taking two Xanax. Arriving at the yoga studio, the faithful are welcomed by this bit of existential doggerel, penned by some groovy mystic named Do Hyun Choe:

Stillness is what creates love.

Movement is what creates life

To be still, and still moving—that is everything.

For those of us prone to snicker at certain fallacies of quantum mechanics, a mention of “Schrödinger’s yogi” will get you no laughs at the yoga studio. Crickets. Trust me. But, on my oath, I did my best to act with some semblance of decorum in the midst of folk keen on integrating their mind, body, and spirit. In fact, I love the idea of yoga, of a metaphysical synthesis. Ginsberg, like Mary, was onto something.

I placed my mat next to Mary’s. We are met by a yogi called Blythe who greets everybody kind of creepily, in a voice you’d expect to belong to Asmodeus, King of the Nine Hells, right before he eats your soul—soothing, but toothy and affected. Blythe also glistens.

I whisper to Mary, “I think our yoga instructor is a high-level demon, not that you care.”

“Even more reason to do exactly what he tells you,” Mary whispered back, with more than a hint of annoyance.

First, we begin with the child’s pose, a basic yoga maneuver, albeit one I can’t perform. The aim of the child’s pose is to get you focused on breathing, as you essentially sit back on your heels, lay your torso on the ground, arms above your head, and contemplate life. Tremendous in theory, but in my case, this elementary contortion topples me over like a late-stage inebriate. The specter of Ginsberg shakes his head, I feel the constrictor, but I try. Mary looks at me tenderly, either because she feels sorry for me, or she’s just happy I’ve agreed to take part in an activity that means very much to her.

This look will change dramatically as we are then told by Blythe to do something called Surya Namaskar, or a sun salutation. This procedure is a series of 12 movements specifically designed to cripple anyone with fully developed vertebrae. As we are instructed to leap backward into high plank, I hit the floor with a dramatic thud, and, in my panic and embarrassment scream, “For those about to rock, we salute you!” I have shed my Clash and my fatigues, for the most part. When I am upset and embarrassed, AC/DC puts me at ease. But now I want to shoot my toy Kalashnikov in the air in frustration at my deliberate fraudulence. What an incorrigible dilettante. What a failure of mind/body mechanics. Somewhere the solar deity is hiding in a closet, pretending it is night.

Mary, Blythe, and the class participants all recoil in horror as I writhe around the cork floor like a maniac, ululating in heavy metal death throes.

“Tyler, wait in the damn car if you can’t be serious.” I have already scooped up my yoga mat and begun to charge across the hypotenuse of the studio toward the exit, bowling over sun-saluters, water bottles, and hemp yoga bags crammed with Upanishad cookbooks and magical oils filled with the meaning of life. Yoga is a disaster. I knew it would be. Would Mary be able to forgive my latest transgression against cosmic unity? I hoped so. Ginsberg most certainly did not.

He once wrote, in a poem entitled “Is About”:

Who cares what it’s all about?

I do! Edgar Allen Poe cares! Shelly cares! Beethoven & Dylan care.

Do you care? What are you about

or are you a human being with 10 fingers and two eyes?

Existence is serious business. This is what Ginsberg was trying to tell us. One cannot perfect wisdom, and to snicker and scoff at the yogis and the patchouli and the energy stones, and often things involving leotards or holding hands with strangers in a hot room that smells like Asmodeus’s armpit is to presume a kind of perverse perfection of a perverse kind of wisdom. I want to be through with juvenile folly and silly death. What is poetry, but liquid yoga? What is love, but sitting in a blazing hot Civic, hoping to see Mary emerge from the yoga studio with the grin that starts at her forehead and works its way down?

On the long drive home, I agree to tag along to her tai chi session next week.