1. ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ (1963)

The first track on the Beatles’ inaugural album, Please Please Me (1963), ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ explodes with a sense of urgency and abandon equaled only by the opening strains of ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand,’ the song that would prefigure the group’s triumphant first visit to North America in February 1964. Composed by McCartney and Lennon in the McCartneys’ living room while playing hooky, ‘I Saw Her Standing There’ bespeaks the same teenage amalgam of hopeful romance and ready acceptance that marks the band’s other works of the era: ‘Well, she was just 17 / You know what I mean / And the way she looked / Was way beyond compare.’ Lennon later observed, ‘We were just writing songs á la the Everly Brothers, á la Buddy Holly, pop songs with no more thought to them than that—to create a sound. And the words were almost irrelevant.’ Indeed, the song’s lyrics merely revolve around a kind of innocuous optimism—but, as an audibly excited McCartney counts off the beginning of ‘I Saw Her Standing There,’ it signals the ushering in of a new sound that would forever change the face of popular music.

2. The ‘middle-eight’ on ‘And I Love Her’ (1964)

With a knack for crafting ‘middle-eights’—the eight-bar refrains that characterize their songwriting in the early 1960s—the Beatles were already searching for new musical vistas as early as A Hard Day’s Night (1964). With ‘And I Love Her,’ the band easily assumes a stirring Latin beat. Ornamented with Harrison and McCartney’s flamenco-like guitar arpeggios, ‘And I Love Her’ swells with the rhythmic intensity of Ringo Starr’s bongos and Harrison’s intermittent claves.

For McCartney, this song is nothing short of a watershed moment. His enormous catalogue of romantic melodies and ballads finds its origins in ‘And I Love Her,’ and a line can be drawn from its composition to the emergence of such classics as ‘Yesterday,’ ‘Michelle,’ ‘Let It Be,’ and ‘The Long and Winding Road.’

3. George Harrison’s sitar accompaniment on ‘Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)’ (1965)

On Rubber Soul (1965), the Beatles effectively signaled the expansion of their musical horizons via Harrison’s well-known experimentation with sitar music—the exotic, microtonal flavor of which would adorn such Beatles tunes as ‘Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)’ and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’s (1967) ‘Within You, Without You.’

In ‘Norwegian Wood,’ Harrison’s sitar lines accent the flourishes of Lennon’s haunting acoustic guitar. But they also provide a curious palette for Lennon’s confessional lyrics about an extramarital affair. As with ‘I’ll Be Back’ and ‘I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party’ from Beatles for Sale (1964), ‘Norwegian Wood’ represents a significant departure from the watery love songs that accounted for the band’s initial parcel of hits. The lyrics themselves—far from underscoring love’s everlasting possibilities—hint at something far more fleeting, even unromantic: ‘She asked me to stay and she told me to sit anywhere / So I looked around and I noticed there wasn’t a chair.’

4. ‘A Day in the Life’ (1967)

Fans and critics alike often refer to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band as popular music’s first ‘concept’ album. In truth, though, the Beatles’ notion of a fictitious ensemble peters out after ‘With a Little Help from My Friends,’ the album’s second track. The concept ‘doesn’t go anywhere,’ Lennon later remarked. ’But it works ’cause we said it works.’ Most significantly, Sgt. Pepper saw the Beatles erasing the boundaries that they had been challenging since Rubber Soul and Revolver. ’Until this album, we’d never thought of taking the freedom to do something like Sgt. Pepper,’ McCartney observed. ‘We started to realize there weren’t as many barriers as we’d thought, we could break through with things like album covers, or invent another persona for the band.’ And with ‘A Day in the Life’—the album’s dramatic climax—the Beatles virtually re-imagined themselves as recording artists. Filled with variegated sonic hues and other assorted sound effects, the song contrasts Lennon’s impassive stories of disillusion and regret with McCartney’s deceptively buoyant interlude about the numbing effects of the workaday world. The song’s luminous, open-ended refrain—‘I’d love to turn you on’—promises a sense of interpersonal salvation on a universal scale. Yet Lennon and McCartney’s detached lyrics seem to suggest, via their nuances of resignation and unacknowledged guilt, that such a form of emotional release will always remain an unrealized dream. As the music of the Beatles and a studio orchestra spirals out of control and into oblivion, that thundering, massive piano chord punctuates and reverberates within the song’s unflinching melancholic ambiance.

5. ‘I Am the Walrus’ (1967)

Inspired by Lewis Carroll’s nonsensical poem ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter,’ ‘I Am the Walrus’ opens with Lennon’s Mellotron-intoned phrasings, meant to replicate the monotonous cry of a police siren. As the song’s spectacular lyrics unfold—‘I am he as you are he and you are me and we are altogether’—Ringo’s wayward snare interrupts the proceedings and sets Lennon’s intentionally absurdist catalogue of images into motion. While an assortment of cryptic voices and diabolical laughter weave in and out of the mix, Lennon’s pungent lyrics encounter an array of ridiculous characters—from a ‘crab locker fishwife’ and a ‘pornographic priestess’ to the ‘expert texpert choking smokers’ and Edgar Allan Poe himself. When ‘I Am the Walrus’ finally recedes amongst its ubiquitous mantra of ‘Goo Goo Goo Joob,’ the song dissolves into a scene from a BBC radio production of Shakespeare’s King Lear. Described by Ian MacDonald as ‘the most idiosyncratic protest song ever written,’ ‘I Am the Walrus’ features Lennon’s most inspired verbal textures, as well as the Beatles’ greatest moment of musical diaphora: in one sense, ‘I Am the Walrus’ seems utterly devoid of meaning, yet at the same time its songwriter’s rants about prevailing social strictures absolutely demand attention.

6. Side two of the White Album (1968)

These nine tracks, from ‘Martha My Dear’ through ‘Julia,’ illustrate the White Album’s stunning eclecticism—the true measure of the album’s resilience. McCartney’s baroque-sounding ‘Martha My Dear,’ with its crisp brass accompaniment, meanders, rather lazily, into Lennon’s bluesy ‘I’m So Tired.’ Lennon later recalled the song as ‘one of my favorite tracks. I just like the sound of it, and I sing it well.’ Written during the Beatles’ famous visit to the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s retreat at Rishikesh during the spring of 1968, McCartney’s folksy ‘Blackbird’ imagines a contemplative metaphor for the civil rights struggles in the United States during the 1960s. The sound of a chirping blackbird lightly segues into Harrison’s uncomfortable but unforgettable political satire, ‘Piggies.’ The song cycle continues with McCartney’s countrified ‘Rocky Raccoon,’ a track that shifts, rather astonishingly, from the disquieting universe of cowboys, gunplay, and saloons into a gentle paean about nostalgia and loss. Ringo’s ‘Don’t Pass Me By,’ with its barrelhouse piano chorus, abruptly steers the sequence into the sudsy world of the beer hall. Originally entitled ‘Some Kind of Friendly,’ the song became a number-one hit—why not?—in Scandinavia. One of McCartney’s finest blues effusions, ‘Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?’ explodes from the embers of ‘Don’t Pass Me By’ and brilliantly sets the stage for the side’s final two numbers, ‘I Will’ and ‘Julia.’ A soothing melody about the tenuous argument between romance and commitment, ‘I Will’ remains one of McCartney’s most memorable experiments in brash sentimentality. Arguably his most powerful ballad, Lennon’s ‘Julia’ memorializes the songwriter’s late mother while simultaneously addressing his spiritual deliverance at the hands of ‘ocean child’ Yoko Ono, his newfound soul mate.

7. The guitar lick at the end of ‘Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Monkey’ and the piano melody on ‘Sexy Sadie’ (1968)

A moment of pure excitement and adrenaline, the guitar riff at the conclusion of ‘Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except for Me and My Monkey’ accentuates an otherwise peculiar song about social politics with the bruising panache of rock-and-roll. A rhythmic burst of high-octane modulation, the guitar phrasings exemplify the breadth of the band’s now-extraordinary musical prowess. As Lennon’s acidic lullaby to the Beatles’ experiences under the Maharishi’s dubious tutelage, ‘Sexy Sadie’ bears mention for its salacious lyrical contents alone: ‘We gave you everything we owned just to sit at your table / Just a smile would lighten everything.’ In terms of sheer artistry, though, the song reveals the band in full aesthetic throttle. As McCartney’s tinkling piano phrases spar with Harrison’s bristling guitar, ‘Sexy Sadie’ maneuvers effortlessly through chord changes and one harmonic shift after another. When the song finally ascends to its closing musical interchange, the Beatles’ instrumentation and Lennon’s spellbinding vocal coalesce in a breathtaking instance of blissful resolution.

8. George Harrison’s guitar solo on ‘Something’ (1969)

Harrison comes into his own on Abbey Road, the Beatles’ magnificent swan song: the unbridled optimism of Harrison’s ‘Here Comes the Sun’ is matched—indeed, surpassed—only by ‘Something,’ his crowning achievement that none other than Frank Sinatra would call ‘the greatest love song of the past 50 years.’ For much of the song, Harrison’s soaring guitar—his musical trademark—dances in counterpoint with McCartney’s jazzy, melodic bass, weaving an exquisite musical tapestry as ‘Something’ meanders toward the most unforgettable of Harrison’s guitar solos, the song’s greatest lyrical feature—even more lyrical, interestingly enough, than the lyrics themselves. A masterpiece in simplicity, Harrison’s solo reaches toward the sublime, wrestles with it in a bouquet of downward syncopation, and hoists it yet again in a moment of supreme grace.

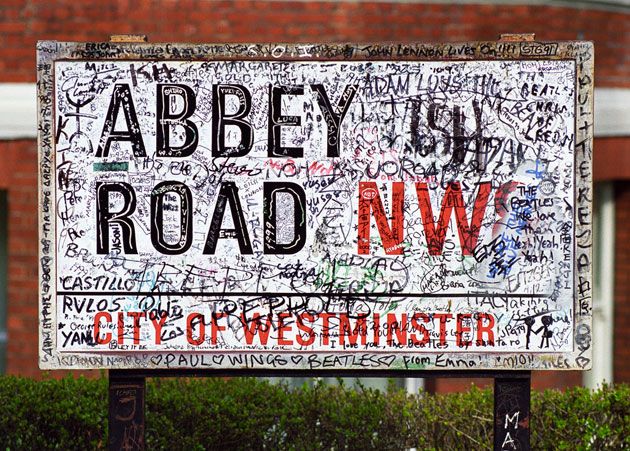

9. The Abbey Road medley (1969)

The medley that concludes Abbey Road and, with that, the band itself, essentially consists of an assortment of unfinished songs. Beginning with ‘You Never Give Me Your Money,’ McCartney’s plaintive piano strains give way to Lennon and Harrison’s dueling rhythm guitars. As Harrison later observed, the song ‘does two verses of one tune, and then the bridge is almost like a different song altogether, so it’s quite melodic.’ The lyrics bespeak the tragedies of misspent youth and runaway fame: ‘Out of college, money spent / See no future, pay no rent / All the money’s gone, nowhere to go.’ The song’s bluesy guitar riffs segue into the chorus of a children’s nursery rhyme: ‘One, two, three, four, five, six, seven / All good children go to heaven.’ Later, in ‘Golden Slumbers,’ McCartney resumes the medley’s earlier themes with a deft reworking of Thomas Dekker’s four-hundred-year-old poem of the same name. As the medley progresses toward its symphonic conclusion, the song’s bitter nostalgia—‘Once there was a way to get back homeward / Once there was a way to get back home’—yields itself to a larger realization, in ‘Carry that Weight,’ that we inevitably shoulder the past’s frequently irredeemable burden for the balance of our lives. In ‘Carry that Weight,’ McCartney acknowledges his own culpability in the Beatles’ dissolution, yet his rather humbling, self-conscious lyrics extend an olive branch to his increasingly distant mates: ‘I never give you my pillow / I only send you my invitations / And in the middle of the celebrations / I break down.’ From ‘You Never Give Me Your Money’ through ‘The End,’ his lyrics impinge upon the inherent difficulties that come with growing up and growing older. Only the power of memory, it seems, can placate our inevitable feelings of nostalgia and regret—not only for our youthful days, but for how we lived them. Appropriately, McCartney concludes the medley with, in Lennon’s words, ‘a cosmic, philosophical line’: ‘And in the end the love you take / Is equal to the love you make.’

10. ‘You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)’ (1970)

Recorded by the band in 1967, completed by Lennon, McCartney, and the Beatles’ faithful roadie Mal Evans in 1969, and released as the B-side of ‘Let It Be’ in 1970, ‘You Know My Name (Look Up the Number)’ is a uniquely comic moment in the group’s discography. ‘We had these endless, crazy fun sessions,’ McCartney fondly recalls in Mark Lewisohn’s The Beatles Recording Sessions (1988). A pastiche of lounge-style vocal stylings and Monty Pythonesque humor, the song features the late Rolling Stones guitarist Brian Jones on saxophone, Lennon playing the maracas, and Harrison on the xylophone. From its soul-pounding blues introduction to the song’s swanky samba refrain, ‘You Know My Name’ is propelled—in unforgettably comic fashion—by Lennon’s hilarious falsetto vocals and the dappled chorus of grunts and mumbles that mark the tune’s sizzling conclusion. In its own peculiar way, ‘You Know My Name’ brilliantly captures the spirit of the Beatles’ remarkable pop-musical career: their personality, their willingness to experiment—to whatever results—and their irrepressible humanity.