Captain Mike Smith of Beaufort, N.C., piloted the Challenger shuttle that exploded shortly after launch from the Kennedy Space Center on Jan. 28, 1986. He fought in Vietnam as a fighter pilot, earning the Distinguished Flying Cross, and clocked 200 days of flight time in a career that led him to become a Navy test pilot and N.A.S.A. astronaut. Born the day Hitler committed suicide, as the Soviets raised the victory banner above the Reichstag, and going on to pilot a shuttle with the space race over and the Soviet Union’s power waning, Smith lived the Cold War’s entirety. He was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

It’s an honor to share my name with Captain Mike Smith. I also share it with a head coach of the Atlanta Falcons, a Canadian actor, a managing director of Columbia Records U.K., and 2,635 other people in the U.S. and U.K.—and that’s not even counting the 43,328 Michael Smiths who don’t officially shorten their name. As a group, we share a powerfully straightforward name that reveals little—but as a writer, I have different needs. In short, I thirst to give a more distinctive crown to my writing.

I’m not looking for an aesthetically minded costume change, just a little distinction from other Mike Smiths, especially the evil Mike Smiths. After I began writing I was asked twice if I was the Mike Smith who writes things like “They hate you because you’re white.” It’s embarrassing to be confused with that Mike Smith. My ordinary name should be a blessing, a digital disguise, and a foil to curious Googling, but the more it plagues me, the more I feel a change is in order, something deeper and more meaningful.

Some join the French Legion in search of a new identity. Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, the Venuezuelan revolutionary and murderer responsible for a deadly 1975 raid on the O.P.E.C. headquarters in Vienna, was assigned the nom de guerre Carlos by a leader of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. ‘The Jackal’ was appended to the name by a Guardian reporter when a copy of Frederick Forsyth’s novel The Day of the Jackal was found in a flat Carlos rented in London. The Guardian were incorrect that the book was his, but the name stuck and received added notoriety when Carlos was featured in the novel The Bourne Identity as the world’s most dangerous assassin, and later in Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six.

Unlike Carlos the Jackal, control of Mike Smith’s future authorial identity is my own. Unlike Carlos the Jackal, I can decide how I want to present myself to the world. I don’t even need to commit atrocious crimes to do it—a pen name ought to be enough. Not something to hide behind, but something to really get behind.

As Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum moved west, her name did too. She rinsed the color from a wonderful name to become the monochromatic queen of concrete and steel as Ayn Rand, hiding her name to protect her family in the Soviet Union from persecution following the publication of her work. Thankfully, I don’t need to shelter my family or reassert my heritage and identity; I live under the same United Kingdom as my name implies. I don’t want a name that speaks a different language, just an English one warped distinctive.

Like Rand, Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski anglo-scythed his name to become Joseph Conrad, while Charles Lutwidge Dodgson chose to lead us down the rabbit hole as the more welcoming and pleasant Lewis Carroll. Their changes create simple and uninvolved names: quick, glass-clear, and glass-smooth. My name is short and uninvolved but it’s jagged, finger-snap quick, and too mundane to stand alongside words I want to be anything but.

Respect for simplicity and for truth are good bearings to set as I seek a name, remembering that pen names are not devices to please.It’s tempting to follow Archibald Leach across the Atlantic. He was raised in a troubled and unhappy family in Bristol, England, and left for life in the circus, travelling to America with the Bob Pender stage troupe. When the troupe left, he stayed on to pursue a stage career. Later assuming that the success of Clark Gable was in large part due to his initials, he took the stage name Cary Grant, having tried out the name Cary Lockwood for a while.

I’d happily be pulled across the Atlantic for good, but considering how unhappy U.S. custom officials were with how light my luggage was when I visited last, further explaining a false name and my intention to take American jobs wouldn’t help my chances of getting in or being allowed very long. A pen name may cause more problems than it solves, but those who have assigned themselves new identities and found new luck with new names make me want to change my name even more, and start afresh.

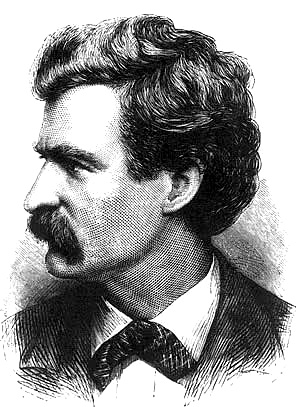

Samuel Clemens took the name Mark Twain as he traveled on the Mississippi. It was a simple change that at face value seems uninspiring, but the name masks an inner strength and power, not obvious to all, but revealing to those who know its origin. Clemens took the name from a mariner who used it to sign reports of the Mississippi River’s condition. For steamboats to safely sail, sailors would measure a river’s depth with a rope knotted at one-fathom intervals, calling out each “mark” as it broke the water: mark one, mark twain, and so on. Twain explains the name as “a sign and symbol and warrant that whatever is found in its company may be gambled on as being the petrified truth.”

The name carries something living in a body strong with truth. Respect for simplicity and for truth are good bearings to set as I seek a name, remembering that pen names are not devices to please. Twain’s crown of petrified wood is grander than gold.

Eric Blair adopted the pen name George Orwell to avoid his parents’ social embarrassment by the publication of Down and Out in Paris and London. In the book, Orwell tells of drinking a lot of wine and washing a lot of dishes as a plongeur in Paris, and how he tramped around southeast England trying to understand the nature of vagrancy and poverty. His pen name combines the patron saint of England, George, with his most beloved English site, the Orwell river near his home.

When I follow the same formula, I become a cheap lawyer who likes cheap puns (David Dart). But at least we’ve established some ground rules.

As any good writer would, I sat down and began writing to friends, asking for help coming up with a distinctive name that embodies truth, transparency, and carries an inner strength, but isn’t too quirky. I don’t want to be the one wearing the crown upside-down.

Friends were no help. Mike Pedal was accurate for the cycling bit (I enjoy cycling), but sounded made up—I imagine each introduction would cause a stranger to cringe. Pete Fence was a suggestion with merit, but at two syllables it buzzes along the ground and then sinks back into the mud. Smith Michaels sounded a little too much like a pen name—so it’s honest—and Smith as a first name was intriguing. But it’s back to front—like backwards clothes, unbearably uncomfortable. But I’d take it over Cyril Bunting, another suggestion, any day. Cyril Bunting is a clown who tattoos a tear on his face for each year since he got fired from the circus. It’s no writer’s name. None of these are.

A prison psychologist broke the deadlock during a long two-hour session, and the consultation may prove to be the best money I never spent. We passed the two hours on a delayed train from London to Exeter. After having sat silent for the previous hour, neither of us reading our books, just staring at other people reading their books, no scenery to see through windows at night but our own reflections, the stopped train gave us a reason to talk.

I already had a middle name, I just hadn’t thought to use it.The psychologist said she worked with two prisoners who share my name, so she sympathized with my quest to find a pen name and suggested that instead of a fake nickname, or cool alias, I should invent a unique middle name to distinguish myself.

But I already had a middle name, I just hadn’t thought to use it. It’s written on my credit card and my driving license. When I told her my full name, one of the few times I’d ever said it aloud, she loved it, and considered my problem solved. She didn’t ask whether I had perhaps repressed some traumatic experience that caused me to reject my full name, and didn’t suggest further therapy to help me work through this new reality. It was just a name.

We went on to talk about pubs, and she explained that she regularly went to a pub in Exeter that was one of my favorites, and we agreed that we’d surely meet there soon. She explained how much more friendly she is in a pub, rather than at the end of the long train journey at the end of a long weekend. But train delays aren’t so bad. I had, after all, regained my middle name. After leaving the train and the station I said goodbye and drove home, but all that talk about pubs and prisoners made my desire for an alternate identity seem so trivial to everything else going on, so unneccessary.

It equally made my middle name, my real name, shine brighter: It was exactly what I was looking for.

“Deri” is Welsh for oak. It is the part of my name that indicates I am not English, but British, born in north Wales. Derry, a city in Northern Ireland that translates in Irish as Doire, comes from the same word. The Celtic roots running through the name binds it to me. Even better, the tree of my childhood was a great oak which was too tall to climb, and oak trees seem so very English.

Deri. Oak. It’s perfect really. Forget the face that launched a thousands ships, most of those goddamn ships were built of oak. The heart of the British Empire and its naval fleet are made of thousands of planks of it. Oak panels even line the debate chamber of the House of Commons.

Let’s leave the deliberate literary schizophrenia until we need to really spice things up.As usual, despite looking far and wide, the answer was found at home, on my birth certificate. The name is pronounceable, and it’s honest: Mike Deri Smith. I have nothing to hide, so why obscure my full name? The effort a pen name would require must be a hundred-fold greater: I’d have to create and manage another whole self, create clear boundaries and be wary to not let it take over my real name when I’m not looking. One name is enough. One should really be the limit. Let’s leave the deliberate literary schizophrenia until we need to really spice things up.

I will plant an acorn on this day every year, and allow future generations to stopper their wines with its cork, build their ships and parliaments from its boughs, and smoke their fish and their cheeses on its ashes. The Mike Smith of the literary world—whose work you likely don’t know, and have probably mistaken for someone else’s anyway—is dead. Viva oak! Long live Mike Deri Smith!