I knew how it was supposed to go. There would be a visit from a striking bald man in a wheelchair, visiting my parents to tell them I was a gifted child who needed to attend his special school for gifted children in Westchester. My parents would acquiesce, saying it was better for me to be with people more like me, and I would go, and in Westchester I would be told I was an X-Man now.

It never happened, but that was how it was supposed to go.

I was a bookish child with allergies and asthma, unable to run a single lap around the track at school without gasping. At the age of nine, I needed to have weekly shots in the spring and summer. After the first shot, I left the doctor’s office, pain radiating along my little arm, feeling the unfairness of how I had to do this when other people didn’t. My dad brought me into the corner drug store and told me that because I’d been such a good boy during the shot, I could choose one comic book.

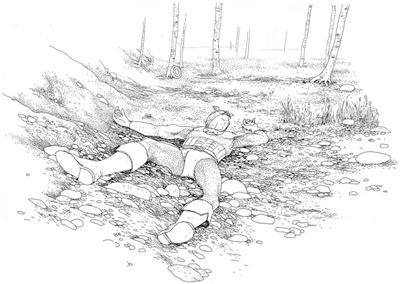

Heroes in comics, I soon learned, were often sickly, brainy, and miserable, until a freak accident/military experiment/mutant gene/mystical talisman changed their lives forever. I eventually came to wish the allergy shot had something radioactive in it, or that I would find a stone at the beach with magical powers, or that I would simply discover one day that I had the ability to fly—falling out a window, jumping to escape a bully, I’d lift off into the air and escape whatever the harm was. I longed for the accident that would reveal my powers. But looking back at myself standing at the comics rack, the pages flipping faster and faster, I can see, the comic itself was the talisman. When I read it, this world where I was small and sickly went away, and another one, where heroes defeated villains, where the sickly became super-powerful, replaced it.

I would forget the pain in my arm.

Soon I could speed-read, so that I appeared to be leafing through a comic while my dad waited, and I would read one and leave with another. The one comic I read in the store turned to two, then three.

“I’m just looking,” I told my father, or the pharmacist.

On that first day I chose the X-Men, “Giant-Size X-Men #1.” It was thicker than the others. In it, the original team of X-Men was captured while on a mission to a volcano island that turned out to be a mutant creature. A new team was recruited to help them—the first really multicultural, multiracial team in comics, with African, Native American, Japanese, Irish, and Russian team members, and one who didn’t appear human at all.

Growing up with a white mother and a Korean father, this imaginary world looked more like the one I knew. We’d moved from Guam to Maine a few years earlier—I missed Guam desperately. There I’d been one of many kids of many races; in Maine, I was the only mixed-race child I knew, besides my siblings.

The world I longed for was the world of the X-Men.

2.

Lately I have been thinking a lot about a sickly miserable boy who became a superhero, by the name of Captain America. He first appeared in December of 1940 in a comic book about an illustration artist who, after being rejected as physically unfit to be a soldier, is approached to participate in a military experiment, one that makes him into a super soldier.

In the first issue of Captain America, which sold over a million copies, he famously punched Hitler in the jaw. It is natural to imagine that we were already fighting the war over there when this comic appeared, but we were not. We were still sitting out World War II.

We went into the war shortly after this comic appeared.

You could ask of the Captain America comic, “Did we go to war as a result of the comic?” or “Did the comic depict our unconscious desire to go to war?” This is a difficult question. Most of the people who could answer it are dead. Many of them died fighting that war.

3.

Some real-life Captain Americas: Last May the lawyer Gordon Erspamer filed suit against the CIA and the U.S. Army on behalf of the Vietnam Veterans of America and six soldiers in particular who claimed to have been the subjects of medical experiments conducted by the CIA at the Army’s Edgewood facility in Maryland, starting in the 1950s and extending to the 1970s, involving “nerve agents, nerve agent antidotes, psychochemicals and irritants,” according to a report by the Government Accountability Office, or GAO. From an article Bruce Falconer at Mother Jones wrote on the lawsuit:

At least 7,800 U.S. servicemen served “as laboratory rats or guinea pigs” at Edgewood, alleges Erspamer’s complaint, filed in January in a federal district court in California. The Department of Veterans Affairs has reported that military scientists tested hundreds of chemical and biological substances on them, including VX, tabun, soman, sarin, cyanide, LSD, PCP, and World War I-era blister agents like phosgene and mustard. The full scope of the tests, however, may never be known. As a CIA official explained to the GAO, referring to the agency’s infamous MKULTRA mind-control experiments, “The names of those involved in the tests are not available because names were not recorded or the records were subsequently destroyed.” Besides, said the official, some of the tests involving LSD and other psychochemical drugs “were administered to an undetermined number of people without their knowledge.”

4.

My fantasy of being a mutant was something that helped me keep going.

At the supermarket when people asked my white mom, “Whose little boy is this?” sometimes I would defiantly insist I was hers, sometimes say nothing, but I’d glare each time as if I had eyebeams that could vaporize them. When she let my hair grow long, they then asked “Whose little girl?” and I would have to tell them I was a boy. No one else was like me, except my sister and brother. The other Asian American or Asian immigrant students I knew were “monoracial”—of a single ethnicity—a term I didn’t know then, and they enjoyed an uncomplicated identity that people could easily be comfortable with or despise. I understood quickly, the rest of the world was like this, so far as I knew, and I was something else, something blurring in their vision. Whenever someone wanted to accept me or reject me, it was as if the features of my face they most needed to see to like or hate me became prominent. White people who liked me said my eyes were green, Asians who liked me said they were brown. White people who didn’t like me told me my eyes were slanted, Asians who didn’t like me said they were round. White people who wanted to insult me called me “chink” and “flatface,” Asians who wanted to insult me acted like I didn’t understand what they said, or they said some insult fast, in Korean, and laughed—they treated me like a white outsider. And both told me the racist jokes each side told about the other. On those occasions, the teller, no matter their ethnicity, told the joke in front of me without any expectation I’d be offended.

In the bathroom I sometimes imagined myself as I would have been with either a white face or an Asian one, looking into the hazel part of my eye and seeing the green extend across all the way, or watch it shrink back, covered by brown. The freckles would blanch away or extend until they met and my face turned darker.

It would have been easier to be a mutant, I decided. I sometimes told myself I was one, that it was the only explanation for the reason so many people asked me “What are you?”

When I was 16, on a trip to visit relatives in Korea, a Korean cousin asked me, of Americans, “How can you tell them apart?” I remember I shrugged. By then, ennui had set in. The world was doomed by this stuff, it was clear to me then—was there any point in pointing it out? Each side took so much pleasure in the insults, it was never going to end. How can I tell any of you apart, I wanted to say, with your mutual need to feel superior to someone from another culture? Which one of you is really any different?

On the plane home after that visit, I was shocked to see the plane full of babies with the same reddish-brown color hair as mine, many with hazel eyes, all of them mixed Korean and white.

Go ahead, I wanted to go back and say to my cousin, back then. Do your whole “We’re better than them” thing while you still can.

No one ever asks me why I love the X-Men, even now, but if they had, the answer I’d give is: They were the only ones who knew how I felt. A group of people different from everyone else in the world had found each other—I envied that, and when I read the book, it was like I’d found them too. It was a story that protected me, a dream about difference that let me keep some pride when nothing else helped. I didn’t know how to even ask for what came just by reading that comic.

If I were writing a comic about this, it would end with me surrounded by them, flying, floating to safety in an updraft that Storm, the one who controlled weather, would have created out of the air. And I would move with them to New York and later San Francisco, which I actually did do—places with more races, with people who were mixed.

5.

There’s a comic Freud used to illustrate his famous essay, “Interpretation of Dreams,” called “A French Nurse’s Dream.” The connection between comics and dreams is apparently so direct even Freud did not feel it necessary to explain why he would use a comic to illustrate what he meant. In it, a French nursemaid is walking her young charge along the street when he begs her to let him pee on a street corner. She allows him, and soon notices the child has produced a stream that is filling the street. Soon it is like a river, and a crew shell rows by in the street, then a gondola, then a sailboat, and finally a steamship coming down the river, the boy peeing the whole time. In the last frame the nurse awakens to the child standing in his crib, crying.

The dream protects the dreamer while the dreamer sleeps, Freud said. This is the point he illustrates with the comic. The sleeping nurse’s unconscious kept including the child’s crying in this succession of scenes, until finally she could no longer be kept from waking.

Captain America punching Hitler in the jaw is Captain America knocking him across the room with the weight of the culture.

In a graphic-novel class I taught at Amherst College, I liked to pass out comic books on the first day. Many students had never read them. I asked them to describe what they saw. They often smirked as they leafed through the pages, commenting: “Huge muscles,” “huge breasts,” “tiny waists,” “everyone is very good looking,” “costumes appear painted onto the body,” “no one looks like this in real life.”

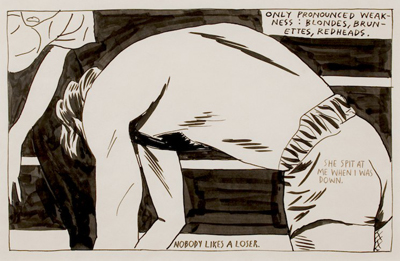

The superhero fantasy is a fantasy of being superior to our adolescent fears of sex and death. It is the dream that you will always be sexy and always be safe from whomever or whatever may kill you. It is often the fantasy of being the most dangerous man or woman in the room, and thus, also the sexiest. Superman, for example, or his bad-boy opposite, Wolverine. Wonder Woman isn’t a comic about a real female warrior—Wonder Woman is about being stronger than any man who might force her to do something, about being strong enough to choose when she might want to be touched, and yet sexy enough, which is to say, attractive-to-men enough, for people to still want to do so.

The superhero fantasy is also the fantasy that the law is not enough, and what’s needed is someone willing to break the law in order to deliver justice.

Comics regularly get in trouble for depicting the forbidden, and have for years. You could imagine, then, that comics are revolutionary, that they could foment turmoil and rebellion. But so far, I think we use them to stay asleep. Superhero comics in particular. We read them, we watch them now in movies, increasingly—comics are the new hot film properties, complete with serious stars and directors, huge budgets. We dream of heroes fighting evil together in the dark theater, but when we wake, we live alongside evil, uncomplaining.

What, then, are we dreaming?

6.

In May of last year, I stood in Midtown Comics, in Manhattan’s Times Square, with my most recent haul for that week. Thirty-five years had gone by since I was the boy with the allergy shots. I had eight issues in hand, all Marvel. The X-Men, of course, but also the Avengers, the team Captain America has led for decades, which is now in several formats, spinoffs, and storylines: the Secret Avengers, the New Avengers, the Mighty Avengers, the Thunderbolts, as well as Captain America’s eponymous series.

I stood in the checkout line and flipped through them and noticed something: Almost all the characters were white.

The X-Men still has some racial diversity, but there are many teams and spinoff titles now, and most of them are entirely white: the X-Men, the New Mutants, X-Force, X-Factor, the Uncanny X-Men and the Astonishing X-Men, to name a few. And the main characters across those titles—Beast, Colossus, Kitty Pryde, Emma Frost, Cyclops, Wolverine—are all white (yes, fellow fanboys and fangirls, the Beast is technically blue and furry, but he was born Caucasian). That particular month, a storyline was concluding about how the world’s mutants were welcoming a mutant messiah figure named Hope, who would save them from extermination, in a story called “Messiah Complex.” Hope was white, with red hair, her protector during her childhood also white, and he was protecting her from an X-Man from the future, convinced she was going to be the end of the world, and… he was black.

The sight of Obama had triggered some protective instinct, atavistic and intense, and everyone was giving white people prizes. And now were bringing back Viking gods for good measure.

Granted, there’s a way we could imagine that as progress of a kind, to allow black men to be villains again. But there are no other majors in that story who are not white. There are two Asian X-Men: Armor and Psylocke, who often have functioned as token Asians, both Japanese, in supporting character roles, though Psylocke has become more prominent in a story where she is also on a black ops team, and as of last month, Armor got her own major storyline. But Storm, once a major character for decades, is, after a marriage to the hero the Black Panther, an African prince, now a minor character. This is what’s called “sending a bad message,” that after you marry you lose your central role if you’re a woman. The most diverse team in the X-Men universe is the New Mutants, with Latino and black characters. X-Factor has one Algerian woman. A poster sent to stores to promote the “Messiah Complex/Second Coming” series featured Hope at its center surrounded almost exclusively by white X-Men, plus Psylocke, though her features are drawn as Caucasian.

While the X-Men were busy chasing their white Messiah, the Avengers’ comics in my hand had storylines featuring three blond white heroes—Captain America, Thor, and the Sentry—at the center of a series-crossing “big event” storyline Marvel was promoting heavily also, and also reaching its climax last May.

Captain America, Thor, and the Sentry, I noticed, looked like brothers. Thor and the Sentry could have been twins, with their long blond hair, enormous pecs, and biceps as big as their heads.

I am a fan of the writer, Brian Michael Bendis, but was incredulous at the series, called “Siege,” featuring an America that woke up one day to find Asgard, mythic home of the Viking gods, intruding into American airspace, hovering above a prairie in Broxton, Okla. This made Asgard a target for one of these black ops teams, in this case an out-of-control squad of heroes the government was also calling “The Avengers,” lead by a villain named Norman Osborn, a.k.a. the Green Goblin, a former defense contractor whose powers were the result of a lab accident. The Goblin’s team was composed almost entirely of villain imposters, posing as the real Avengers, in the Avengers’ costumes, with the Avengers’ names, and with the permission of the American government, the idea being they could be redeemed by this kind of service and controlled, kept from villainy by technology. The Sentry, a superhero with a split personality, one light, one dark, had slowly, under Osborn’s manipulations, become entirely the dark version of himself and thus functioned as his own imposter. With a single attack, he and the sham Avengers team bring Thor to his knees.

Captain America sees this and, enraged by it, goes to defend Asgard and bring the imposter team down, and leads the original Avengers onto the field to rescue Thor.

Captain America is having an identity crisis of his own, over whether he can be Captain America again or not—whether it is time for him to allow his former sidekick , Bucky, to take over. He is only just back from the dead again (death is nothing to him), after what was technically a mock assassination plot to steal his identity and use him against everything he’d held dear, and returns to find his former partner in his costume, with his captors hoping to carry out evil in his name. Bucky has been fighting evil in his absence and wearing his uniform and mask. He offers it back to Captain America as soon as he returns. Captain America refuses and declares there can’t be two Captain Americas, but as there’s an extinction-level threat facing them, they go to save Thor, Asgard, and America together.

Three blond heroes, two identity crises. Same principle: to be a capital-H Hero or not? It didn’t feel deliberate, like the work of a propagandist. And to Bendis’s credit, he’s single-handedly revived the fortunes of Luke Cage, one of the first African American heroes at Marvel Comics. But all around Luke Cage, the faces are white, and often blond—not just the three “brothers” of Thor, the Sentry, and Captain America, but the women on the team, too. It felt unconscious instead, part of a series of all-white sweeps across other cultural industries in the last two years—the very white Academy Awards, the very white Emmys, the very white National Book Awards, and so on. It was the superhero version of these things. As if the sight of Obama had triggered some protective instinct, atavistic and intense, and everyone was giving white people prizes. And now were bringing back Viking gods for good measure.

It was the sort of thing you’d expect in a dream about a black president of the United States, in other words, except it was really happening.

Thor kills the Sentry and throws his remains into the sun. The sham Avengers—who have their own comic, the Dark Avengers—go to prison, and are not murdered, as they might be at the end of a real failed black ops mission. Captain America decides to move on, and to allow his sidekick to continue in his place, and, released from being Captain America, as it were, accepts a job from the president as the head of a black ops unit. He, in turn, hires Luke Cage, the super-strong bulletproof black man, to be the new team leader of the public Avengers team. A figurehead with real power, but a figurehead all the same.

This all happened in the middle of May 2010. In America, under the leadership of a black president, in the first year America was to see white births become a minority, this, the biggest story in comics, was about three white men, one of them a white god. And a country in conflict with the ancient white gods they’d left behind. It was the exact opposite of my experience of reading “Giant Size X-Men #1” in May of 1975, which is to say, it was happening 35 years later to the month.

Underneath it all, America dreamt that it was undercover. Deep cover. And if caught, it could not be identified. Its public leader was a black man with bulletproof skin, and its secret leader was a white hero who, in order to do what he must do, should be hidden. As of last year, you could say it was just a story, and that it didn’t mean anything until exactly one year later. Which is to say, now.

7.

In an interview reported by the Minnesota Post with Seymour Hersh of the New Yorker, Hersh spoke of an assassination squad that reported to Dick Cheney and no one else, unknown to other members of the government.

Dick Cheney is an interesting figure in the history of the United States. He is a man who was a young, idealistic Republican in the Nixon White House, who felt that Nixon was brought down by what should be legal, to tape your enemies and know what they did and said and to use this information against them. He felt Nixon was wronged. And so Cheney, as the legend goes, worked tirelessly to create an ‘imperial presidency’ out of the administration of George W. Bush . There were many reports that Cheney made more decisions than Bush did, but the possibility that he had his own death squad, moving in and out of countries, killing targets without the knowledge of the State Department, Congress, or the CIA, is terrifying. And it should be said: This is what is meant by “black ops.”

When do we get a hero who does not need superpowers? And what if he didn’t need to go outside the law? What if our dream was that the law worked, and then it came true?

The report from Hersh has not since been followed up on, but Dick Cheney is out of office, and the Obama administration has repeatedly declined to prosecute the Bush administration, and has, under criticism, kept—and in some cases even expanded—some of the powers of the imperial presidency. Cheney, meanwhile, has a machine that pumps his heart while he waits for a replacement, a transplant. He looks like a diminished version of himself, thinner, frail, except that he has outlived his heart, and this suggests he still has an enormous strength. Of the kind you’d find in comic books.

What then, of the assassination squad, you could ask? Did it leave him once he left office? It is an interesting thing that one of the first people to congratulate President Obama on the death of bin Laden was Cheney himself. Joint Special Operations Command, JSOC, the black-ops team mentioned in association with the office of Dick Cheney, was the team that killed bin Laden.

This, then, is the real-life version of Captain America’s newest assignment. We have the former military contractor who once ran a secret team, we have the secret team under new management, we have a former agent of the United States who became a murderous usurper, a figure of evil that needed to be killed, we have the black leader who is called “Cool Hand Luke.” We note all of this and remember that in a dream, figures are rearranged, if still familiar. And so we can conclude, a little differently from the way it is commonly understood now, that when the report came from President Obama of the death of Osama bin Laden at the hands of a top secret Navy Seals unit operating inside Pakistan without Pakistan’s knowledge, it was the country’s dream come true.

8.

The pleasure of the superhero comic narrative is one in which the villain is known, caught, punished. Brought to justice. I was reading Conor Friedersdorf in the Atlantic, on how a wide variety of prominent politicians and pundits have made room for torture, ranging from George Bush to Rush Limbaugh, Marc Thiessen to Bill Kristol, all the way to Obama, who refused to order the Justice Department to prosecute officials from the Bush administration and the CIA, and in doing so, ignored treaties ratified by the Senate under Reagan. Friedersdorf quotes from an earlier, prescient essay by Phyllis Rose, from the Atlantic in 1986, and useful for us to think of in our relationship to our superheroes:

Righteousness, as much as viciousness, produces torture. There aren’t squads of sadists beating down the doors to the torture chambers begging for jobs. Rather, as a recent book on torture by Edward Peters says, the institution of torture creates sadists; the weight of a culture, Peters suggests, is necessary to recruit torturers.

You have to convince people that they are working for a great goal in order to get them to overcome their repugnance to the task of causing physical pain to another person. Usually the great goal is the preservation of society, and the victim is presented to the torturer as being in some way out to destroy it.

Captain America punching Hitler in the jaw is Captain America knocking him across the room with the weight of the culture. The X-Men going from multiracial to white to needing a white Messiah is the weight of the culture. The Avengers becoming black-ops agents is the weight of the culture. Thor, Captain America, and X-Men movies coming out simultaneously this summer is the weight of the culture. If a comic book can get us into World War II, can one get us out of Afghanistan? When can a hero be someone without a mask, who ends a war?

Why is a nation with a black leader and a future white minority dreaming of white heroes who save the world, and their white god allies? When do we get a hero who does not need superpowers? And what if he didn’t need to go outside the law? What if our dream was that the law worked, and then it came true?

I sometimes think I’ve already had what I wanted from my heroes, all those years ago. The X-Men taught me to survive childhood. But isn’t there more work to be done?