The stomp is how you sell a punch in professional wrestling: When your fist sails harmlessly past an opponent’s head, you bring your boot down on the mat—stomp!—for effect. When you’re on the receiving end, you drop from the hit and writhe. But not too much, or it isn’t believable.

I went to a wrestling show in Aiken, S.C., last month, and brought my friend Alex along. Alex’s wrestling knowledge is encyclopedic, so I asked him to give me the story.

“The key to pro wrestling is the suspension of disbelief,” Alex began as we hunted for our seats in the upper level of the USC Convocation Center. “It’s basically a male soap opera. The characters, the story lines—it doesn’t pretend to be anything other than a peculiar kind of theater.”

The arena was about half-full. Below our section was a concrete floor, rows of folding chairs, and a six-sided ring. “It always looks bigger on TV,” Alex said. This was a T.N.A. “house show,” meaning it was not televised.

T.N.A. is short for Total Nonstop Action Wrestling Federation, which boasts a Thursday night show on the cable channel Spike TV, and competes with the bigger, more famous World Wrestling Entertainment. Lately, T.N.A. has made news by stealing away W.W.E. stars like Booker T and Kurt Angle. But, Alex says, it’s still very much a second-string “fed”—short for federation.

The lights dimmed and the crowd roared. The first match pitted two tag teams against each other. The ring was a flurry of limbs, thrown at each other so as to miss, but just barely. When a wrestler smacked the rubber mat, it sounded like a flatbed truck driving over a pothole. Alex explained the moves as the wrestlers unleashed them: the suplex, the body slam, the flying elbow. Then he started talking about characters.

It was me versus Kurt Angle, who started taunting me, flexing for the crowd with a sinister grin.“A big thing in wrestling is the gimmick,” Alex said. “It’s a wrestler’s persona. Like that guy there, Sanjay Dutt”—he pointed at one half of a tag team. “He’s called ‘The Guru,’ and he walks around before matches, begging for money.”

“That’s his gimmick?” I asked.

“Yep.”

“How is that a gimmick?”

Alex shrugged. “Gurus beg for money, I guess.”

Next was a fight between two women. One was named “Awesome Kong” and the announcer proclaimed that she weighed 278 pounds.

“She’s big,” I said, as Kong sat on her opponent, then threw her like a mannequin. “But not 278-pounds big.” Her braids fluttered in the air.

“Yeah, but it sounds better.”

After mighty Kong triumphed, Booker T took the stage to great applause and pinned a slick villain named Robert Roode. The crowd jeered mercilessly as Roode exited the ring. Alex joined the chorus.

“Boo!” he yelled. Then, pausing, he said, “Roode brings me to an interesting point. In wrestling, there are Heels, and there are Faces. Heels are bad guys, Faces are good. Then sometimes you have Heels who think they’re Faces and they play to the crowd. Or you have Faces with Heel alter egos. And other times, they ‘turn’ a wrestler from one side to another. It gets complicated.”

The lights went up. Intermission. The crowd relaxed. Mothers stroked their children’s hair, friends laughed and nodded along to the music on the speakers. A remarkable transformation—five minutes ago, this mob looked ready to murder Robert Roode or any other Heel who dared to cross them.

“So they’re characters, too,” I said.

“Sure,” said Alex. “We all are.”

We bought sodas and popcorn. Then darkness fell again, and we roared for the main event: a showdown between the champ, Kurt Angle, and Samoa Joe. Angle, a Heel, looked terrifying and anabolic. He wore a wrestling singlet with flames on the side. Joe was portly; he sported spandex pants, no shirt.

Angle took the microphone, thumped his chest, and threatened Samoa Joe.

“All the time,” Alex said, “people ask: ‘Don’t you know it’s fake?’ And I say sure, but so’s everything else we watch. And wrestling actually co-opts that in entertaining ways, like if a wrestler takes the mike to deliver a canned, tough-guy speech and interrupts to say ‘Who writes this stuff?’ There are meta-moments like that all the time. It’s wrestling’s way of nodding to the audience. They know that we know everything is choreographed.”

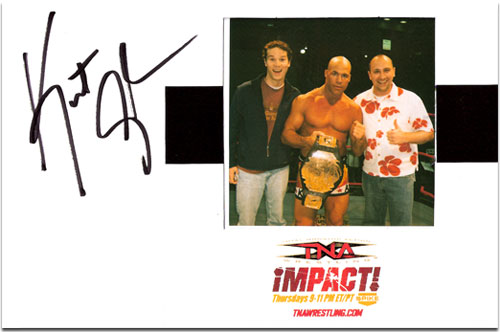

Kurt Angle pummeled Samoa Joe, and departed as the lights went up again. Show over. Then he returned to the mat, drinking bottled water. T.N.A. announced that people could take a Polaroid with him for free; a line formed. Angle chatted with fans while pictures were taken. Alex and I got our turn and ducked under the ropes.

The camera finally flashed, and I felt mildly disappointed. Then I imagined myself donning a singlet with my name embroidered on the front.As we stepped into the ring, I remembered what Alex had said about wrestling, that the key is the willful suspension of disbelief.

“You know,” I said as we flanked Angle for our pose, “writers can relate to that. We fabricate. We have to. Like, do people believe this is how our conversation really went? That I remembered all of this perfectly? That I didn’t manipulate the events of this evening and the things we’ve said—for effect?”

“Of course not. It didn’t actually take T.N.A. this long to snap our photo. And they charged us $20 cash for it. And we never ordered popcorn. Who cares? None of this is realistic. But it’s part of the fun. You write to entertain, you fashion people into the necessary roles for your readers. And you know that they know it’s an artifice.”

Up close, Kurt Angle looked less intimidating. He was short. His steroidal head was shaved, and reminded me of a peeled, squishy potato.

“I think I get it now,” I said. “The audience wants to believe the stomp is a punch. But they’re also waiting for that nod, that wink admitting the fakery of it all. Everybody’s inside and outside the joke. Everybody’s a character.”

The camera finally flashed, and I felt mildly disappointed. Then I imagined myself donning a singlet with my name embroidered on the front. In my mind, my neck thickened and my hair became long and stringy. It was me versus Kurt Angle, who started taunting me, flexing for the crowd with a sinister grin.

“Who’s writing this stuff?” Alex asked.

“I am,” I said. “Sorry if it’s over the top.”

Angle bounced off the ropes and lunged at me.

“One question I still have, Alex. Even though we give them the wink they want, we’re still lying to them, feeding them fiction. Does that make us Faces or Heels? Or Heels who think they’re Faces?”

Alex answered with a question. “Did I ever tell you the story about Eric Young? He’s another T.N.A. wrestler, who’s not here tonight.”

“No,” I said, throwing a punch. Stomp!

“Eric’s gimmick is that he has the mind of a child. He’s scared of the other wrestlers’ costumes,” Alex continued, ducking Angle’s elbow. “So one of the wrestlers has to explain to Eric that it’s all just a sort of playacting—it’s that wink again, really. The guy goes up to Eric and—this is important—he goes up and he says ‘Kid, everybody has an alter ego. You just need to find yours.’”

The worlds of professional wrestling and contemporary fiction aren’t so far apart. Our writer immerses himself in the Total Nonstop Action Wrestling Federation, to the point of being flung across the ring.