Illinois is yelling at me. I’m on the floor of the Democratic National Convention, waiting for my signal to pass out signs to three different states. But Illinois would like to have them now. All of them. I get my cue and start passing.

As I hand out the signs, my underpants begin hiking up. My arms are overfull, and I’m surrounded by thousands of people. By the time I finish, my underwear is well above the line of my pants—and Illinois is still screaming. I turn around and see a CNN cameraman filming me from behind.

For most of the past decade I’ve been a full-time writer and editor. I’ve logged a lot of quality time with teacups and tidy desks. As I’ve told many friends, working at the convention is a lot like emerging from a comfortable, warm bath, drying off, and then leaping into a vat of ferrets.

Whip It Good

“Visibility whips” are the volunteers who distribute signs and small souvenirs on the convention floor. This is my job. One of the job requirements is the ability to break into a full sprint whenever necessary.

After our first few sign passes, we learn to hold them so we don’t get nasty paper cuts on our forearms when someone grabs them unexpectedly. We also learn how to say “excuse me” so it never sounds like a request. Mostly, we exchange uneasy glances when we learn we’re passing out convention souvenirs rather than signs. We call the souvenirs “chum,” as in the hunks of raw meat you throw into the water to churn up sharks. Everyone’s clamoring for signs, but even statesmen in somber suits will maim each other for a keychain flashlight.

Flag Waving

Our timeline for the speeches is rough because many run long. (You may remember how Al Sharpton’s six minutes stretched into 20.) Whips wait in the entry halls and then move into our sections when it’s about time for a new round of signs.

In many cases, this means that we’re standing within the crowd for ten minutes or so while the speaker finishes a speech. This is when things get a little heated. The crowd sees what we’re about to hand out, and they begin to flock.

I have a precarious embrace around 500 small American flags. Several people try to snatch a bundle or two from my arms without asking. I reserve my nastiest looks for these folks; I am disappointed in them.

When I begin to pass the flags, many people stand, gesture frantically, and call out to me. Of course, there aren’t enough flags for everyone, and most people understand that this is just the way it is. Still, when my arms are empty, I hear one man’s voice above the crowd. “Girl!” he yells. “GIRL!”

My spine tightens, and I turn slowly to find the gentleman a few rows back. When he sees he’s caught my attention, he pops his eyes and flexes his jaw. The effect is comedic, crazed, and disproportionately intense. I am briefly grateful he had to pass through a metal detector to be here.

Fingers splayed, he gestures in wide circles toward his chest, like a magician willing his hypnotized subject to come forward. He wants to talk to me. He wants to chat about how he did not get a flag.

I blink at him in disbelief, then laugh and trudge back upstairs to gather signs for the next push.

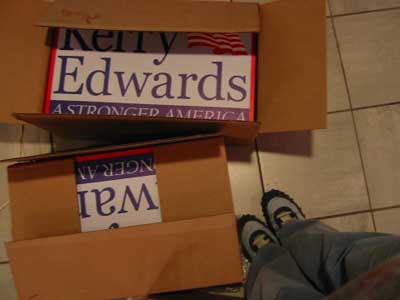

Signed, Sealed, Delivered

Over four days, we’ll pass out 169,932 signs (those last two are extra-large posters for New Mexico’s governor Bill Richardson). Most are mass-produced—the ones that nod in a sea of approval during major speeches.

The whips are here to help ensure that there are no “sign clots” or empty rows when a network camera scans our section. The audience needs to have signs at the exact right moment, needs to know when to hold them up, and needs to know when to put them down. As you might imagine, producing and dispersing these signs—and providing instructions to go with them—is no small organizational task.

First off, because the Secret Service is a bit touchy about these things, the signs must be made in such a way that no one can use them as weapons. That means no wooden stakes as signposts. Shelly, the floor manager for many a past convention, special orders thousands of miniature mailing tubes for signposts instead.

Also, because the fire marshal isn’t keen on having huge piles of highly flammable paper signs in the building, each night’s signs are stored in large trucks outside. These are unloaded in the mornings and placed in holding rooms backstage.

No Rest for the Weary

My husband Bryan has been working in event production for years. He’s taken two weeks off work to be here, as a visibility manager, which means he helps organize and run the sign operation. The weekend before the convention his team realizes there’s a problem.

The signs are safe in their trucks and ready to go, except for one small thing: In the chaos of sign construction, everyone has been tossing signs into the trucks willy-nilly. This is an organizational nightmare. Each truck should be loaded with signs for a particular day, so they can be stored and unloaded easily.

So now each of the three trucks must be reloaded so it contains the signs for its assigned night. Unfortunately, nearly all of the signs are wrapped in opaque garbage bags, which means that the bags must be ripped open, the signs identified—and sometimes re-bagged—before they can be loaded into the correct truck.

Once that problem is solved, a new one emerges. Some of the signs are late coming back from the printer, and, on the eve of the convention, someone needs to go get them. Unfortunately, the area around the Fleet Center has already been secured by the Secret Service. The Secret Service, it seems, isn’t fond of large trucks driving into its secured areas.

Bryan picks up the signs, and drives them back to the Secret Service Marshalling Yard. There, he waits until midnight to be processed. He drives the truck through a huge X-ray machine (farewell, viable sperm), and then waits as a bomb-sniffing dog examines the vehicle. It sniffs the bumper, the engine, Bryan’s bag, Bryan’s shoes, the glove compartment, and each bag of signs in the back.

Several hours later, a police officer escorts Bryan and the signs into the secure area and volunteers begin unloading them. That morning, I meet Bryan with a freshly ironed shirt and a cup of coffee. And he’s ready for a new day.

The System

The convention hall is divided into about nine major zones. Each zone has a coordinator, who is in radio contact with the two visibility managers, who give the cues. The zone coordinators each have a team of about five visibility whips.

In the afternoon before opening night, zone coordinators receive rough timelines that indicate cues for when the signs should go up. Coordinators gather their whips and take signs from the large holding areas over to mini staging rooms closer to their zones. At about 4 p.m., the action starts.

We wait in our staging areas until the zone coordinators get a radio call to move into position. In some areas of the hall, the radios aren’t working as well as they should be. The visibility managers shout, “GO-GO-GO-GO-GO-GO-GO-GO-GO!” when it’s time to pass the signs. The idea is that at least one or two “GOs” will get through the spotty reception and to the zone coordinators.

When coordinators hear “the go,” they signal to the team. At this point, the visibility whips (that’s me) give about half the signs to political and delegate whips, who are associated with the individual states, and the rest of the signs they pass out directly to the audience.

We pass the signs with instructions, “Raise this when Mrs. Edwards gets onstage, please” or “Wave your flag when Willie Nelson sings.” This message is reinforced by the political whips, who also get radio instructions from backstage. After that, we cross our fingers.

Do You Know Who I Am?

On the final day, the visibility team realizes that the tall vertical signs in front of the podium will block the photographers’ shots of Kerry during his speech. Twenty-five volunteers spend an hour trimming sign handles with X-Acto blades.

That night, the fire marshal closes the floor early. We get advance warning and are told to get as many signs as possible into the auditorium before we’re shut out.

We have about half the signs inside before the floor closes, and most of us are stranded outside. We go to each door looking for sympathetic security checkers. At this point, only a quarter of our team is on the floor for the sign passes.

A locked-out delegate sees me rushing around in my yellow safety vest and assumes I have authority.

“They’re not letting anyone on the floor!” he yells.

“I know, I’m so sorry. The fire marshal shut things down because there’s too many bodies.”

“Do you know who I am?”

“I don’t, sir.”

“I have to be out there!”

“I’m so sorry, sir.”

“Don’t be sorry. Do something about it.”

“Sir, I have zero power.”

“Well, who the hell does have power?”

“The fire marshal.”

“Well you tell your superiors that I’m locked out. You just tell them and see what they have to say about that.”

“Yes, sir.”

He wanders back to the door, too flustered to realize that I still don’t know who he is. He turns his tirade on an 18-year-old security volunteer, who shakes her head a few times and then avoids eye contact.

Where Are the Balloons?

Despite the frantic pace and the aching muscles, the convention has hundreds of small beautiful moments that make everything worthwhile.

On our second flag pass, I decide to test a theory. As I give people the flags I say, “There won’t be enough of these for everyone. We’ll need to be kind to each other.” Each person smiles at me, mumbles “of course,” and passes the flags along politely. Magic.

A few times a night, everyone in the convention hall sings something in unison. There’s nothing so lovely as thousands of people singing “America the Beautiful.” Then again, I also find myself tearing up at everyone dancing and singing along to “Johnny B. Goode.” Of course, by this point I haven’t really slept in a week. On occasion we pass out handmade signs drawn in thick Crayola marker; Kids for Kerry has been working on them for weeks. They say things like, “Kerry is da’ man!” or “Kerry rocks my socks” with a small drawing of argyle socks in the corner. In the back room, we read through every one.

For every creep on the floor, there’s someone who pats me on the back and tells me what a good job I’m doing. Guam gives me an enamel pin because I make sure they get signs in the far back corner. A few nights later, I get a pin from West Virginia. “West Virginia loves you,” the delegate says. I think West Virginia may be tipsy.

Pausing to look out as everyone raises the signs, my breath catches. When Teresa Heinz Kerry walks on stage to see the field of bobbing “We love Teresa!” signs, my friend Birgitte grabs my arm. “Do you see how touched she is? We did that. We did that!”

And it’s true. When everything goes as planned, the effect can be breathtaking: thousands of people who have come to the same conclusion at the same moment, thousands of people who couldn’t agree more. All of us would like a new president, please.