I grew up for the most part in Tallahassee, Fla., in the home of my mother’s parents. According to my grandparents, the living room in which the family spent most of our evenings had formerly been a garage. On the back wall, about 30 feet across, the previous owner had painted a large, full-color Confederate flag. I never saw the flag on that wall because it was almost immediately painted over by my grandparents, sometime before I was born, and eventually covered in wallpaper. If only the legacy of that hateful emblem was so easily destroyed.

By now you’re aware of the massacre in Charleston, SC, how a young white supremacist by the name of Dylann Roof entered the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church on Wednesday night, sat for an hour with a Bible study group, then murdered nine African Americans there with a handgun. Any attempt to discourage meaningful associations between the race of the killer and that of his victims is by now utterly without merit. Roof put up a manifesto on a website stating his beliefs and motivations clearly. He believed in the supremacy of the white race above all others, and held a special animosity toward black people. In his own words to a former roommate, he intended to begin a second Civil War.

Roof—like practically all American white supremacists, affiliated or otherwise—used the Confederate battle flag as a symbol of his hateful ideology. His car had a license plate on the front displaying the flag and support for the Confederate States of America (CSA), and pictures from his website show him holding the flag. All of this makes perfect sense considering that the Confederacy, by its own founding documents, was explicit in its intent to maintain both white supremacy and African bondage; anyone who tells you otherwise is ignorant at best. Pathetically, this symbol is not only pervasive in many states, but still flies over some public and government buildings. Even as the US and South Carolina state flags were lowered to half-mast in Columbia last week in honor of Roof’s victims, the Confederate flag in front of the State House flapped breezily, snidely even, at the top of its pole.

Why in the name of anything holy should the Confederate cause be memorialized at all?

In an embarrassing display of political cowardice, South Carolina lawmakers pointed out that state law actually prevents them from lowering the Confederate flag, ever.

Growing up in the South, you see a lot of Confederate flags. They fly over people’s homes, and they’re commonly spotted in the back windows of cars and trucks. They’re emblazoned on clothing, on bumper stickers, and sometimes tattooed on human skin. Often, they’re found in association with text stating that “the South will rise again.”

I was never friends with people who still celebrated the Confederacy; I was raised to know better. When confronted with the obscenity that is this flag and what it represents, a majority of its defenders are likely to spout the tired cliché that the flag represents “heritage, not hate.” This is bullshit. It’s as much bullshit as anyone who begins their racist statements with the phrase “I’m not a racist, but…” It’s bullshit because the heritage those same defenders are supporting is founded on hatred. And I should know because it’s my heritage.

My family has long been filled, on both sides, with zealous investigators of our genealogical record, which is partly how I grew up knowing that one of the most celebrated figures in our family line is John Neely Bryan. Ever heard of him? I’ve always been quick to tell anyone I’ve met from Dallas that my great-great-great grandfather founded the city. It’s long been a point of some pride in my family, and I grew up echoing it. More and more, however, I’m not exactly certain why I share this bit of family trivia as if it’s something to be proud of. I personally had nothing to do with the founding of Dallas—it’s not even a favorite city of mine. Increasingly, I’ve come to assume that the land on the banks of the Trinity River that Bryan claimed to build his home and trading post had been stolen in some way from Native American inhabitants of the region (cf. the history of the whole of North and South America). But thanks to a recent trip by my brother to Dallas, we’ve learned a little more about what kind of man our great-great-great grandfather was.

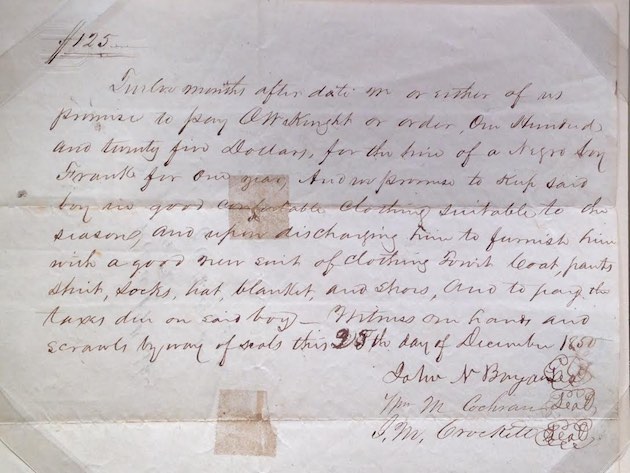

On display in the Old Red Museum, across the street from where Bryan’s original cabin is preserved, one finds a yellowed piece of parchment on which a contract was written. According to the plaque on the display case, “For $125 and a new suit of clothes, John Neely Bryan rented the services of a slave from A. W. Knight on Christmas Day 1850.” The contract itself states the payment was to be made “for the hire of a negro boy Frank for one year.” So there it is. My heritage both materially supported and benefited from slavery. My blood is tainted by this injustice. My heritage is repulsive.

Sadly, this is not the only instance of racial injustice an ancestor of mine perpetrated. Bryan and his son, John Neely Bryan, Jr., were both registered Confederate soldiers. Though they never saw any combat, having been stationed in Texas, they supported the CSA with their service. Bryan, Jr., would go on to name his son, my great-grandfather, after Confederate general Robert E. Lee, supreme commander of the CSA by the end of the war. And that’s just my dad’s side!

Going back through my mother’s family, we find a great-great-great-great-great grandfather, Richard Stith of Kentucky, who owned at least 23 slaves according to that state’s 1820 census. His son, Daniel, owned at least one also according to the 1850 slave schedules. The Stiths and their participation in the slave trade were only recently brought to my attention, which got me wondering about one of my friends from Tallahassee who has the last name Stith, and if it’s possible his ancestors were once the property of mine. Notably, Daniel Stith was also cited in the draft records of the Confederate States Army.

Personally, I’m horrified. But my story, my existence, is not unique. If even half of the estimated million Confederate soldiers had children, that would equate to at least tens of millions of living descendants today. A less conservative estimate could put that number over 100 million. No, the only thing special about my case is the effort some of my relatives have put into researching our family line. Most people simply haven’t bothered to learn the truth about their ancestry, but plenty would be likely to discover what I have, a heritage of white supremacy and slavers.

What honor do we owe Confederate soldiers? They fought on the losing side of one of the most inhumane causes in human history, perhaps second only to that of the Nazis. I don’t believe this is an exaggeration. The Civil War—begun in earnest with a Confederate siege and bombardment of the US Army in Fort Sumter—claimed over half a million lives and destroyed numerous American cities, all so a minority group could be kept in chains. (Ever notice how proudly neo-Nazis in America display the Confederate flag? Does that not in itself put to rest any notion of “heritage, not hate”?) Why in the name of anything holy should the Confederate cause be memorialized at all? Why should we continue to esteem their hatred for and oppression of blacks by flying the battle flag of their soldiers? Especially considering how widespread their toxic and violent ideologies remain in America to this day.

There’s simply no heritage of the Confederacy worth preserving. The Confederacy was trash.

Do I hate my ancestry? No. Honestly, I feel too far removed from these people whom I’ve never met to feel love or hate. I admit I find it fascinating, but isn’t feeling fascinated by my family’s sordid history a form of privilege? The very fact that I know the names of my relatives going back that far is a privilege in itself, as I’ve learned in discussions with African-American or Jewish friends about their family histories—many of which stop much more quickly. But I am ashamed of this heritage. I understand that my ancestors and others who fought for the Confederacy were human beings, just like everyone else, complex and filled with good and bad qualities. But that doesn’t mean we are obligated to venerate the bad qualities, the loathsome parts of our heritage. My family tree has its poets, scientists, doctors, and teachers, too. I simply see no reason to honor the fraction of my heritage dedicated to white supremacy. And really it’s only a small fraction of American history, too. The CSA lasted four short years, over 150 years ago. How many more causes and political movements have come since then far more worthy of acknowledgment?

Granted, there are many in white America who can’t trace their existence today to the South and the slave trade, those who may think their people are innocent. They’re wrong. All white Americans at the time benefited from slavery and anti-blackness, as all white Americans today benefit from white privilege. I’ve met a lot of people in New York City, for instance, who seem thoroughly convinced that this is a Southern issue. The fact is that the factories and merchants in the North bought, traded, and shipped agricultural products generated by slave labor. Earlier, around 1700, more than 40 percent of New York City households held slaves—the second-highest proportion of any colonial city after Charleston. By the time of the Civil War, New York City was the economic powerhouse of the nation. Which is one reason that New York City’s mayor at the time, Fernando Wood, suggested the city’s secession from the Union in early 1861 with the backing of many business leaders similarly filled with anti-Lincoln and anti-Union sentiment. While New York City eventually (and in some cases begrudgingly) came to support the Union over the Confederacy, the point is that slavery is white America’s shame, from coast to coast, Yankees too.

And I’ve been from coast to coast of this country, and there’s hardly a corner in which you can’t find a Confederate flag. It may not be prominently displayed on public land, but private hands are holding them tightly. I’m not interested in legislating against such personal property, but there’s no excuse that taxpayers anywhere should further subsidize “the stars and bars.” It’s bad enough that Alabama, Florida, and Mississippi’s state flags still incorporate the Confederate battle flag in their state flags’ designs. (Georgia used to, but changed to incorporating the design of the CSA’s first national flag in 2003 because they’re so fucking clever. We see you, Georgia.) Many states, such as South Carolina, just like having the flags around, officially.

Many Republican leaders are suggesting South Carolina be allowed to deal with this issue on its own, without the input of outsiders—just as generations of white supremacists have argued that their states be allowed to deal with slavery, segregation, interracial marriage, and other civil rights abuses in their own way, in their own time. Former presidential candidate Mitt Romney took to Twitter to point out that the flag is “a symbol of racial hatred,” and that it should be removed “to honor #Charleston victims.” President Obama tweeted in response that Mitt has a “good point,” so they do agree on something. Other responses to Mr. Romney were less coherent.

But why stop with South Carolina? Our government should not and cannot allow a single state in this nation to give symbolic support to present-day Confederates like Roof. That an open symbol of the Confederacy should still fly over any public building in this country is beyond absurd; it’s grotesque and treasonous. As the flag of traitors to the United States of America, it represents a violent assault on our ideals of democracy and liberty. It promotes white supremacy, which is antithetical to the equal protection of all citizens under the law.

This whole discussion and the events leading up to it are shameful, and let’s be perfectly clear: This is white people’s fault. This is white people’s shame, and we have to do something about it. How do we meaningfully honor the victims in Charleston? How can we discourage support for white supremacy? How do we honor the millions of victims of white supremacy going back to the Civil War and before? We probably can’t do anything to ever atone for so many generations of suffering and hardship, but we can do something small and expedient. We can rid our public spaces of support for the Confederacy. We can demand our legislators and representatives—by any means necessary—to strip every public building and stretch of land of any recognition of those who rebelled against our United States and who brought death and destruction to our nation rather than recognize the liberty of a portion of its citizens. We can metaphorically spit in the eyes of our hateful ancestors who believed that their fellow human beings belonged in bondage. We can do this now, in our time. There are no excuses. There can be no delays. There’s simply no heritage of the Confederacy worth preserving. The Confederacy was trash. My ancestors, like yours, were wrong to do what they did, and I’d think after 150 years we can own up to that.

In the long run, we can also push to see every statue of a Confederate leader torn down from their public squares, and every bridge, road, or other landmark renamed if they were christened for anyone who joined the fight. And while illegal, and not exactly meeting the definition of civil disobedience, I also implore anyone willing and able to tear down and burn any Confederate flag they find, ‘cause fuck ‘em. After all, during the era of slavery, many brave men and women broke the law and risked their lives to help runaway slaves escape injustice. The least you can do is burn some asshole’s flag. It’s probably just a misdemeanor.