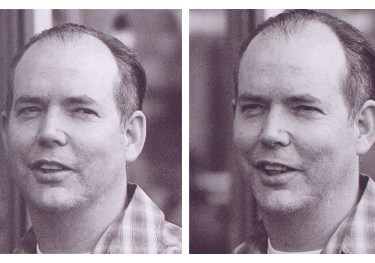

Douglas Coupland

It's a good world when Americans and Canadians can still get along. A conversation with author Douglas Coupland about Columbine, art projects, pus-bags, and that sexy country of sin up north.

Canadian Douglas Coupland is the author of eight novels, Generation X, Shampoo Planet, Life After God, Microserfs, Girlfriend in a Coma, Miss Wyoming, All Families are Psychotic, and his latest Hey Nostradamus! He has also written three works of non-fiction, Polaroids from the Dead, City of Glass, and Souvenir of Canada. He attended the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design, the Hokkaido College of Art and Design, Instituto Europeo di Design and the Japan/America Institute of Management Science. Doug Coupland grew up and lives in Vancouver Canada and, among other projects, he is at work on his next novel currently entitled Eleanor Rigby.

Hey Nostradamus! travels back to 1988 to a high school cafeteria shooting that—as it must—profoundly alters a suburban community. The story is told through four voices: one of the victims, Cheryl; Jason her husband, eleven years later, as his chemical dependencies show his inability to cope with his wife’s death; Heather, Jason’s lover who tries to redeem herself after Jason mysteriously disappears; and finally ending in 2003 with Jason’s father, Reg, an obsessively religious man trying to reconcile his family’s destruction.

* * *

Robert Birnbaum: You probably weren’t aware of this when you were writing Hey Nostradamus! but recently there have been two other books whose plots revolve around high school shootings

Doug Coupland: I’ve heard of one but I didn’t know there were two.

RB: Francine Prose’s After and Lionel Shriver’s We Need to Talk about Kevin.

DC: Wow! And also there’s Gus Van Zandt’s movie. He’s a friend and just for reasons of geography we haven’t bumped into each other in years. Next thing, I read he’s won the Palm d’Or for Elephant. Holy crap! I have a theory why this may be the case. I started this book right on my birthday, December 30, 2001 right after September 11th, and there was a collective soul in the air and unprocessed ideas that still hung around. I wonder if it will be at least a decade before someone in America does a really smart Angels in America type play set at Windows on the World or something. So, there was all that soul in the air and as a seed crystal…well, the Columbine shootings, in particular, which are just enough in the past that we can be a bit more objective about them and see where they are. [pause] I mean this idiotic woman at a reading a few nights ago said, ‘But we don’t have high school shootings anymore.’ I’m like, ‘Can you believe she said that?’ And another person said, ‘Well, you’re from Canada, you don’t have high school shootings.’ ‘No thank you, we have…’

RB: That was my next question.

DC: We had the massacre at the Ecole Polytechnic in Montreal on December 6th. It’s almost like a national day of remembrance. Of course we have had that. Does Europe have them? I think even Europe has had them. There was one in Germany last year, I think.

RB: In the case of your book, you seem not to be concerned with explaining or theorizing about this mayhem.

DC: I think the killers get far too much attention.

RB: In the news?

DC: Yeah and even my mother went to the Trench Coat Mafia website and she’s sixty-four. You mentioned that beautiful title After. It’s definitely in the air and all I know is I wanted to do the book and I never begin a book without knowing the ending. That’s rule number one.

RB: This seems to be a time in which there is much favorable commentary about Canada—at least in the circles I travel in and in what I read. And, of course, in other circles there is outrage… gay marriage and legal marijuana…

DC: We went from being boring little Canada to a sexy country of sin overnight.

RB: Hendrik Herzberg wrote a wonderful ‘Talk of the Town’ piece in The New Yorker.

DC: We are not used to being trendy or hip.

RB: Does that mean anything to you?

DC: It means something in that back in the ‘90s we were told on every TV show that we were going to be fully absorbed into the American experience by 2001, 2002 the latest. And that any sense of political or cultural sovereignty would be over. The boundaries would just be a weird afterthought. And suddenly against all of that prediction, it’s never felt so different to be Canadian. [pause] Not being American, I don’t know how it feels to be American but I think it is a different thing to be an American now.

RB: It feels like national identity is in flux for many people who haven’t been knee-jerked into saluting the flag…

DC: I think right now and I am not doctrinaire politically but I do think a lot of the centrist point of view, now they are beginning to see, ‘Uranium really…oh okay. And how much? Has the national agenda been hijacked? Is it a witch-hunt? Is it real? How much of it is theology? How much is pure politics?’ I mean, how far back does it go? Pinochet and Chile was all a result of the Monroe Doctrine, so what doctrine are we seeing the very tail end of here? It’s also strange, my first TV memories are of Vietnam and there was Donald Rumsfeld, [incredulous voice] he’s still here! That is just…that is really strange.

Oh god, I hope your readers are still here at this point because most Americans – Canadian anything and they really will turn the page. I’m warning you.

RB: Yes, but back to Canada. Carol Shields just died.

DC: Oh God yeah. She was lovely.

RB: And also, apparently, the director of the Harborfront Book Festival in Toronto quit because of controversy over, the usual reasons, the direction of the festival.

DC: Greg Gatenby quit? Holy shit, that’s huge. Are you kidding? When did this happen?

RB: It was reported yesterday.

DC: Fuck. Sorry, I shouldn’t be swearing. That’s amazing.

RB: Is this a big thing?

DC: It is the best reading series acknowledged around the planet. They get the best people. They are treated the best. Greg made sure all the writers and writers only and not other people had dinner together. And so you would be sitting at the table and right next to you is Larry Kramer and on the other side of you would be Zadie Smith or something. Oh boy, that’s news to Canadians.

RB: Toronto is reputed to be a big book city, very literary, however that is judged. What about the rest of Canada?

DC: The entire economy of Canada is equal to the state of Texas. And it’s very thinly distributed. So it’s only in Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver where you get any amount of critical mass. I mean, any. Remember back in the ‘60s when every country on Earth was becoming independent, Canada included. We got our own flag and all that. There was a national flourishing that began there with Margaret Atwood and the usual suspects. Now, they are all august or dead. It was a very highly subsidized culture. Now the records are finally coming out, you can’t believe how much government money went into doing it that. It’s part of what had to happen with the era. But it is certainly over and now you have…

[Rosie wanders to another table; D.C.: ‘Wait, I’m jealous, I have better treats over here’]

We have had a distribution crisis in Canada and problems with the chains and you name it. And most of the Canadian publishers have gone out of business except for one of two. Even they are just scraping by. And it’s a mess. It’s never been this bad. Canadians are so used to looking to the government for bailing things out and now the government is saying, ‘It’s not there, it’s not going to happen.’ So at the moment Canadians are producing the least amount of Canadian material. Which is ironic and whatever. But it’s the truth.

RB: So might it be odd or counterproductive for you to clearly establish yourself as a Canadian artist?

DC: Oh my God, surely it hasn’t gotten to the point where being Canadian is a hindrance down here?

RB: Well, it wouldn’t come to, ‘Does he speak Canadian?’ But Americans just don’t seem to want to read foreign writers.

DC: You would know better than I [laughs and drifts off] I’m not trying to… I got lost in a Lab moment.

RB: It does seem like Joyce the blonde Labrador in Hey Nostradamus! is lovingly rendered.

DC: Oh yes. My uncle in Ontario… what happens with dogs, I’m sure it’s not the case with Rosie, the females are singled out from that specific breed and then if they are too affectionate or too easily distracted they get pulled out of the system at one year or a year-and-a-quarter. So they are past the puppy stage, so you can’t go through the puppy bonding and they have to find people to have them. They are amazing dogs. My uncle takes them in. Which is why I know a bit more about it.

RB: How many dogs does he have?

DC: Two or three at any given time. They all seem to be hit by cars. It’s almost like you don’t want to ask how the dogs are doing.

RB: Oh no. But we are digressing. You mentioned you started writing Hey Nostradamus! as a reaction to the general sorrow

DC: It didn’t feel like that at the time. It is just this book that wanted to be done. I am finding that 10 years later, 12 years later, you are still finding a reason why you actually did something that far in the past. So to try to analyze it now could be wrong. I don’t think books are entirely intuitive. There has to be some sort of critical experimentation going on. I come from art school and the art world, when you do a show, everyone sees it and God help you if the next one is like the last one. But you have to take some new idea or form you have never done before and expound on it and modify it and then you go ahead. And like we see from the book world—certainly from the industrial side of it—what publishers would really like is that you hone in on your voice or whatever and that you duplicate it as precisely as possible at regular increments over time so that they know exactly how to deal with you and how to sell you or market you or whatever. And I am in this weird niche where I go from one art project to the next.

RB: You are referring to your novels as art projects?

DC: Yes, books.

RB: You designed the icon that is on the cover of Hey Nostradamus! And on your website you have that photograph from the Columbine cafeteria that you entitle ‘Tropical Birds’ after the ATF agent’s observation about all the cell phones ringing. Why haven’t you put more visual elements into your books?

DC: What I am doing now is—I used to do a lot of non-fiction and short fiction and now it’s just long-form fiction, novels, and a lot of visual work. And it’s a conscious decision. The ‘Tropical Birds,’ that happened, I was in Harbor Front (I can’t wait to get to the telephone and find out what the hell is going on there) 400, 500 people and someone’s phone went off in the middle. And it just brought to mind that exact paragraph from the Rocky Mountain News…

RB: Where the ATF agent says the phones were going off and it sounded like tropical birds?

DC: Yeah. So without telling anyone in the audience why, I said ‘Okay, who’s got a phone’ and called them up. ‘Now go to your neighbor and find out their number and phone them and they’ll phone you back or whatever. House, could you dim down the lights?’ Everybody thought it was ‘hee hee, really funny.’ Or whatever, David Byrne-postmodern. And then it went on for a minute and it had its own texture. And then the lights came up and the phones turned off and I told them what I was basing this on. And there was this reaction like everyone had been kicked in the gut. Then in Paris, at the Parisian Literary Festival, I did the same thing except I told people in advance why I am doing it and they did it and then the lights came up and everybody was in tears. There was this gasp of astonishment. Like how often do you hear the singing voice of the human soul? That’s one of the few instances where visual stuff and written work have dovetailed so neatly. I also make these books, one is on Vancouver and that came out a few years ago and then another one came out on Canada before it became sexy or whatever. So it was like, ‘How did you know?’ And I’m like; ‘I don’t know this shit. I just do it, okay.’ I don’t plan it and now I am doing another one because there is all this new material. That’s where the words and picture combination, that’s where it goes—is in those books now. They’ll be for sale in the States in a few months.

RB: Do you read a lot?

DC: Except when I am in the midst of a really fertile period. And then you can only safely reread things that have influenced you in the past. Yes, with the caveat that I reread a lot too.

RB: I find that difficult. There is much that comes my way and I feel the pressure of having so much to read.

DC: Do you really? Oh I’d never think that. No, it’s like every time you read it you will find something new or something that you just didn’t get the first time or the third time or the eight time. On certain books I am up to number 12 or 15 and I am still getting new things. Like Answered Prayers by Truman Capote. Or The ice age by Margaret Drabble. And I just, ‘How did I miss that?’ And at the same time I don’t worry about the work seeping in to the mind osmotically because it is already there as much as it’s going to be.

Okay, here I am, way out of the loop. I read Cold Mountain about a month ago. This is practically after the movie has been made. Wow! What an amazing book! What an astonishing book! And its effect was so potent on me that I had to stop working for at least a week. To sift out how much of this was echoing and how much was osmosis? I do that too, with visual work. There is a certain way I like things to look, certain colors, proportions, and it’s my pathology and it means nothing and it’s just the way I like things to look. Which is an entirely different thing than creating new forms through critical discourse or coming up with a new strategy for generating form whether it’s a sculpture or something on paper.

RB: Rosie come. Lie down

DC: [to Rosie] Oh you haven’t been fed enough. Is he not feeding you enough again?

RB: Your big splash into the literary world was with Generation X and so for a while you were pegged as a ‘Gen X’ writer (whatever that meant), trendy and of-the-moment. But over the last 10 years I would say that your novels are not trendy.

DC: Okay. Today it’s Ted the driver. In every city you go to there is a media escort who drives you to the local NPR and finds out who has been in lately and who is coming up soon, it’s just one of the things you talk about. And one of the things that they really dread is a guy who has his second book. Because whatever the first book was they expect the second book to be like that and it’s never like that. And sometimes there is a third book, though that almost never happens. If you are at book number four and it’s still happening than you are really doing it. So the fourth book…and this is like eight. Plus non-fiction. I must look like some kind of robot or something, but I am not. I feel lazy. I just like what I do and the world is an amazing place.

RB: The young writers I talk with are very much taken up with the impenetrability of the publishing world and the sense of good luck they feel to be published.

DC: I’m the opposite. Everything I have ever written has been published, aside from high school term papers. I didn’t go to university or college. I went to art school.

I don’t think books are entirely intuitive. There has to be some sort of critical experimentation going on. I come from art school and the art world when you do a show, every one sees it and God help you if the next one is like the last one.

RB: Didn’t you go to a management science school?

DC: Yeah, yeah, yeah, and yeah… Nichi-bei Kei-e Kagagku Kenkyu Cho (the Japan-America Institute of Management Science) which it turns out was this dummy fund for the Fujitsu Electronics Corporation to get massive tax breaks on their land holdings. Me, I just wanted to go to work in magazine design, not even writing, in Tokyo. I have always thought the culture there is perpetually 11 years ahead of ours. I go there once a year.

RB: It strikes me that so much of what I see in Japanese print media seems very retro.

DC: They were doing retro 20 years ago, you see. We didn’t start doing retro until five years ago. They are still ahead. In the end I had to leave. You know why? This is really prosaic. Cysts. In tropical temperatures I get cystic acne on my back. From June until September I’ll be this walking bag of pus. And my doctor said, ‘Sorry you can’t live here.’

RB: Otherwise you would choose to reside in Japan?

DC: [Tokyo’s] the only city other than Vancouver, maybe London, I could live in. I couldn’t live in Toronto or Seattle or the Bay area. It would have to be one of those.

RB: You have already indicated the economic proportionality of Canada compared to the U.S. [an economy the size of Texas]. Are there regional differences?

DC: In Canada the way it works is—oh God, I hope your readers are still here at this point because most Americans – Canadian anything and they really will turn the page. I’m warning you. Since 1960, to be Canadian it had to happen in a small town or a farm or it had to be an experience with immigration. Any book that took place in a suburb or metropolis was immediately suspect because they weren’t deemed Canadian enough to generate Canadianocity, for lack of a better word. And now there has been a big mutiny among the younger people they are saying, ‘Screw this! We are so tired. Our parents came from Lebanon, Scotland, or Japan three generations ago so will you shut up about it. We live in a city and we are still Canadians, thank you.’ And there really is this big mutiny going on of young people called the Mutiny against Margaret Ondaajte, which is a code name for that whole block of work that was important but okay…

RB: What about Alice Munro?

DC: She is fabulous. She writes about domestic and feminine experience in a way that’s not pandering or meretricious or condescending. Same with Carol Shields who just died. She was such a sweetheart. I loved her. She had an unfinished novel…

RB: Are your acquaintances writers or artists?

DC: Artists. Do I know any one who writes? Bill Gibson. I’m trying to think of someone else I know…Nope. Everyone is in the visual arts.

RB: Are there many writing programs in Canada?

DC: University of British Columbia has one but they are a lot younger than I am so I don’t feel connected to it. Right now they are considered hot because they all have agents. But again, book number four, the fourth book. Who’s broken out? Dave Eggers, Zadie Smith in recent years. It can still happen.

RB: Given the large advances being given to people like Zadie Smith, there have been articles recently on the pressures on young writers and the smaller windows of time being allowed for an author to prove themselves.

DC: Not Zadie, she’s great.

RB: Do you pay attention to the Internet?

DC: I used to pay a lot more attention to it. It’s too much work. And then my website guy got a real job. [Both laugh] But also, it’s more like a bulletin board than anything. It’s a notice board for what’s coming up. There used to be all this live streaming material and then the bill came in for seven grand a month. Okay, click. I’m noticing that literary journalism is changing. Everyone I know in publishing agrees that it is changing. It’s kind of weird.

RB: I find the literary websites pretty mainstream. The same names keep reappearing, like Zadie Smith or Eggers. The young webloggers still aren’t paying attention to young writers except for the so-called breakout types. Not very adventurous.

DC: I don’t think I have gone to enough sites to know whether to agree or disagree with you.

RB: So it’s not very much a part of your world?

DC: No. I find out literally on the street that Greg Gatenby is gone from Harbor Front. Whereas I can tell you who is having a retrospective at the Guggenheim or what was the best stuff at Dokumenta this year.

RB: Do you watch television?

DC: I get the New York Times. It’s become like the paper Google. And I get two Canadian papers and then I get news-ed out. That’s about it. I watch the Simpsons, this wonderful animation series. Imagine a New Yorker cartoon that goes on for 13 years, that’s The Simpsons. And I watch Law and Order, which is this ultra formulaic, whatever.

RB: What appeals to you about that show?

DC: I don’t know.

RB: You’ve never written a crime story?

DC: Oh no. I wouldn’t know how. If I don’t read them why would I write them?

RB: You watch Law and Order.

DC: It’s like drinking. You know how you are going to feel. When you watch Law and Order you know how you are going to feel.

RB: What about movies?

DC: Almost none. All the interesting stuff is on TV right now. We only have one art house [in Vancouver] so if something comes through you have exactly a 36-hour window and then it’s gone. I end up having to get DVDs. The film industry has been hit with the same thing that books, a massive global release and so it’s all based on first or second weekend. And if it has weak legs, fourth or fifth. As I l look back on what we have been talking about, it’s all been about the globalization of creativity and is there any comfortable point where the marketplace and creativity meet? I don’t think so.

[Here sweetie. Gives Rosie another treat.]

RB: I think she is going home with you. Do you see dark foreboding developments in the world of creation?

DC: In a weird way, the one thing I can say that is good—If someone decides to be a musician now, it means because there is no hope of money at the end of it, it means they really want to be a musician. And if someone is writing now, there is no hope for money at the end of it. So they are writing because they really like writing. So there is this automatic winnowing. Anyone who is mercenary or in it to milk it, unless it is something like genre, which will happen until the sun goes supernova, then… I wouldn’t say it’s good but then it might be a light at the end of the tunnel.

RB: I have sensed on the Internet recently some elation and self-congratulation on the part of webloggers as if a revolution had been started and had succeeded and now the world has been startlingly transfigured. I ask myself, ‘What did I miss?’

DC: And here you are, you have a website and it’s funny to hear from your lips that you don’t feel a part of it. You are totally a part of it.

RB: Whether that’s true or not I am made uncomfortable by the self-consciousness. Like you, I am just going to do what I do. I find it unseemly to sit back and say what I am doing is affecting the world in such-and-such a way. What I want to do is talk to you and we’ll talk and that will go on the website and won’t be making any claims to curing cancer or ending poverty. Of course, I am thrilled to be able to converse at length with people like you and not have to listen to someone say, ‘Keep it short.’ (Or ‘Don’t talk about Canada.’) All this fuss about new media and I have to go back to my favorite story about Chou En Lai, the formidable foreign minister under Mao. When he was asked what he thought about the French Revolution, he said, ‘Too soon to tell.’

DC: Here’s what’s happening in the visual art world, there might not be a distinct corollary but there is probably a connection. Because of eBay the availability and affordability of massive amounts of otherwise previously unobtainable material is out there. I am trying to get this show organized on the West Coast called ‘Hunter Gatherer’ and it could only have happened after 2000. It’s images captured from websites, it’s intense agglomeration of say… there is this woman, Ydessa Hendeles, in Toronto who was a gallery owner forever. She finally said, ‘Fuck it, I’m going to make art myself.’ And good for her. And she went out and did—it sounds abysmal but it’s not—the Teddy Bear project, where she collected 20,000 teddy bears plus the story behind them. And people from the Whitney are going, ‘Oh my God this is unbelievable.’

RB: I’m not sure what you meant about eBay. It seems that it has devalued some stuff because it seems so readily available. And it has created a value for all sorts of other stuff that has become oddly collectible.

DC: As there are more and more people on the planet and information becomes more transparent and more pervasive, the tokens of authenticity that we look for become ever smaller almost to the point where in 20 years like this soiled Starbucks napkin…

RB: [laughs] I remember somebody collecting celebrity garbage…

DC: I worked with Steven Spielberg on The Minority Report trying to figure out what the future is going to look like. And one of the questions was ‘What are aspiring members of the middle class going to be putting on their walls in 2050?’ The answer? Cardboard boxes that you throw out in the back alleys. But if you flatten them out and put them under glass, they are fantastic. And they are so fugitive that no one keeps them. So they are going to be very desirable.

RB: Do you have a collection yet?

DC: I collect everything.

RB: Really?

DC: But it always goes to work. Sometimes I’ll start collecting something and I don’t even know why I am collecting it but I have to. I collected about fifty high school yearbooks from 1980 to 2000. This is before I began work on Hey Nostradamus! Everyone is saying to me, ‘Are you fucking nuts?’ But then I got a phone call from the French government where they have this program where they have French artists do interdisciplinary projects and this guy Pierre Huyghe (even the French aren’t sure how to pronounce it) said I have been important to his work. He came over, and the French find high school a very exotic concept. Cheerleaders to them are like Corrines at the Moulin Rouge would be to us. So we ended up with 47 of these books. We pull out the Exacto, scissors, tape, and found images that had some kind of resonance to them and all we knew was that the images had a power to them, a potency. And then we put together subjective categories—not jocks, nerds—and all these hidden structures emerged. For example, almost every yearbook has a shot where the third best-looking girl in the school is kind of looking around frightened, like a Cindy Sherman photo. And it was so universal. Then we realized there is one nerd in the camera club and then you put them all together and you have this gallery of fear. And then every yearbook has at least one or two people asleep at their desk. But if you assemble them together it seems like a biohazard or bioterror. And there is this other category with the biology teacher holding the skeleton.

RB: These are all inadvertent categories…

DC: Unless you had eBay to collect these 150 books and than cut them up, you would never have known they existed as categories. So that inside the world that we see right now, not just books, this napkin, that spoon, there are all these hidden categories. They are just waiting to be explored and discovered and discussed. That’s what I came away with from that French experience.

As there are more and more people on the planet and information becomes more transparent and more pervasive, the tokens of authenticity that we look for become ever smaller…

RB: You saw a high school yearbook once and then another one…

DC: No, it’s like, ‘there’s something there.’ I’m never wrong. Whenever, I do that… really, I have yet to fuck up. There’s something there I’m just going to collect the damn things and sometimes it takes a year or two or three but then the phone call comes in and that’s the way it works.

RB: You mentioned the French. Does your reputation extend beyond France?

DC: I’m really big in England. France only recently, because I have a better translator. Scandinavia, Benelux, Germany, yeah.

RB: What’s next for you?

DC: Oh boy. The Canada book I was telling you about

RB: What’s it to be called?

DC: Canada II. I’m not even going to camouflage it with a different name, and I’m working on a novel right now. It’s called Eleanor Rigby and it’s about… well, look at all the lonely people where do they come from. And then there are two projects. One for the Canadian Center for Architecture, a museum piece on Modernist building kits. It’s just huge and it couldn’t happen without eBay. You do certain things for different reasons. And in terms of just orgasmic absolute pleasure—it’s called Canada House. I am taking an old house from the 1950s, a generic house. I am going in and spraying everything white inside, filling it up with certain kinds of furniture and then also one-of-a-kind material. These quilts that I have made out of things I have gotten along Canadian roadsides, beautifully stitched, and so you walk into this environment and by spray-painting the house white like this what you are saying is that the house has become historically driftwood itself and it is just one more item, like the things that you are putting inside it. It has to be done for November and I am fucking into it. It’s so great. There is lots of stuff in the works.

RB: So unlike most writers you are not tied to a desk and long hours of solitude?

DC: Well… in the end it is solitude. You are always writing even when you are not writing. I came at it from a different place. I never had the ‘will I get published/’ stigma. I never had that. There are a lot of echoes and baggage I just don’t have. I came through magazines originally, very briefly, and just enough to make me really entirely comfortable with you are not just doing this to jack off, you are doing this to connect with other human beings and they are in on it too. So don’t again, this is a two-way experience. Otherwise it’s just boring. I used to worry that my interest in the world would just wear off one day. It’s a beautiful place and we are lucky to be alive. We really are.