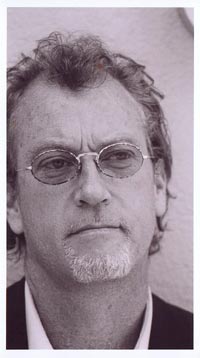

One of the unalloyed joys of my long-standing preoccupation with conversing with writers is when I get to meet some authors for a second time (or in some cases a third or a fourth time). I first met Jon Lee Anderson in the summer of 1997 on the occasion of his well-regarded Ernesto “Che” Guevara biography being published—which was especially poignant for me as I had been in Cuba just a few months before our meeting. Talking with Jon Lee again was remarkably easy, as if we had just left off days before and were resuming our unfinished chat. For this and other reasons (that will be obvious from our talk), it’s clear that the affability he brings to his calling stands him in excellent stead. With all manner of babble flowing and flying around us, one ought never underestimate the value of a journalist who can talk and listen—and can do it almost anywhere in the world.

Jon Lee Anderson is the author of Guerrillas: Stories from the Insurgent World, Che Guevera: A Revolutionary Life, The Lion’s Grave: Dispatches from Afghanistan, and with his brother Scott Anderson, War Zones and Inside the League. His latest book is The Fall of Baghdad. Anderson began reporting in Latin America for the Lima Times in 1979 and continued throughout the ‘80s as he covered the hot spots of Central America for Time, Harper’s, The Nation, and Life. He has been a regular contributor to The New Yorker for the past five years. Jon Lee Anderson lives in England with his wife and three children.

Reading The Fall of Baghdad is an eye-opening experience, not the least because of an increasingly anxious sense, shared by many, that there are important people and policy makers who resist real and readily available information about the Iraqi quagmire and the so-called War on Terror. Jon Lee Anderson is one of a shrinking handful, one is tempted to say, of journalists and reporters who, driven only by their own imperatives and beholden to no communications conglomerate, paint the conditions as they find them, unvarnished and unfettered. The conversation that follows will make that apparent.

All photos copyright © Robert Birnbaum

Robert Birnbaum: You live in Somerset, England?

John Lee Anderson: Near. Dorset. West Dorset. Which is very different from East Dorset. It’s [Thomas] Hardy country. It’s a little tiny town called Bridport—a tiny, tiny market town, right on the sea. The closest place that anyone knows about is Lyme Regis, another little fishing port that John Fowles put on the map. It’s quiet and it’s about three hours from London. We’ve been there for about three years. I haven’t been there much. The family has—we had been living in Andalusia, Spain, for about six years and before that, Cuba.

RB: Spain was directly after the Che book [and living in Cuba]?

JA: It was intended, the place I finished the book and ended up—by 2001 our eldest daughter was about 11, all our kids are completely fluent in Spanish, but she couldn’t get through the English alphabet without breaking into Spanish so we figured it was time to go into the big world again. But not too big. So we moved just two hours away, to England where they have one surviving grandparent, my wife’s mother, and where I’d gone to school as a kid and met Erica, their mother. And it’s a nice, kind of cheerful, healthy part of England. Not too dismal.

RB: When you have a chance to personally experience it. How much have you been there?

JA: Very little. I actually packed the family off on Sept. 4 [2001], I was staying behind in Spain to follow with some things, and Sept. 11 happened. And so I came up to see them. But began making my way towards Afghanistan that very day, in essence. I saw them for three days, in the house we rented, and I didn’t come back until January. And in spring of 2002 I was again a couple of months in Afghanistan and, you know, it’s not much. And then Iraq started.

RB: Are you a war correspondent?

JA: No. No, I am not. I went through a whole period in my youth—[pauses]

RB: [laughs]

JA:—in the ‘80s, when that was what I did. Because that was where I was drawn. It was the era of counterinsurgency and the guerrilla wars of the Cold War in Central America and I spoke Spanish and loved and had lived in Latin America and that’s where I felt drawn. And I would have to say that in the ‘80s I was caught by a kind of fever of war. But I was always fascinated by the organization of violence and the motivations behind people involved in political violence. And I think my initial impulses were also to test myself, like men do. But you learn that fairly quickly. You learn what your level of fear is, and that’s what it’s really all about. And toward the end of the ‘80s, actually early ‘90s, I completed a kind of whole odyssey with my book on guerrillas that I did, which in turn lead me to Che. And really then, for most of the ‘90s I was writing the biography of Che and then I began writing long dispatches for the New Yorker. But they weren’t primarily places of war. Wars had taken place there. They were sometimes destroyed societies. But much of what I was doing until 2001—I had the great luxury and backing of the New Yorker to wander around the world, almost at my whim, looking at places and people that had been forgotten. I guess I was on a two-track thing. I was drawn to places that had been crucial in the Cold War. Places like Angola, or Chile, and writing about them. Because they had been forgotten. And I was also profiling figures of power who interested me. Usually, in a way, it was an extension of that whole interest in violence—what happens when violent power succeeds. So I was doing profiles of Saddam and of Pinochet and of Fidel, but that was less about violence than it was that I had lived in Cuba and was fascinated by it and wanted to go back there. And then Sept. 11 came along. And I felt absolutely compelled—”compelled” is the only word I can [use to] describe [it]—to go to Afghanistan. I had been there in the late ‘80s, and apart from some writing about it which I had done in that book Guerrillas, where I had lived with the mujahedeen, I had not returned. But I felt that I had to be part of this new, whatever this was that was going to come. This tilt in the Earth. So since then, yes, I have been a journalist who’s been in war. But I don’t like the moniker or [pauses] all the attendant sort of paraphernalia that comes with being a war correspondent.

RB: I suspect that you would not sit well with the term “war junkie”?

JA: I don’t like it because it sounds so pathological. And I am aware there are—

RB: There are such people.

JA: Oh yeah. And I have examined myself a lot. I have wondered, “Oh no, am I?” People assume that. They don’t understand why someone like me would put myself in danger so they assume you have a death wish. Or they assume you are seeking something. I don’t think it’s that. Like I say, when I was in my 20s, I felt and I had felt since I was a kid that I needed to go to war because I felt it was something I had to do to become a man. I remember I had a list that I kept amending and updating when I was a child and included—and still have some of them—be a Welsh coal miner. Go to prison. Go to war. Climb Everest by the age of 18. Cross Africa by foot from west to east. I wanted to be an explorer. I was raised on epic tales of 19th-century explorers. And I felt like I was born in the wrong age. These were the kind of achievements that I felt I needed to do. To complete my personal education as a man. To experience everything. I wanted to experience everything, good or bad, so I could be complete. And when I was in my early 20s I wanted to go to war. I felt—I had experienced a lot by then but I had not experienced war. And that was part of my motivation for going to Central America.

RB: There is a young novelist named Ben Jones whose The Rope Eater is a wonderful story of 19th-century exploration. He was very interested in reprising Shackleton’s original advertisement for his expedition and putting it in newspaper classified sections and seeing what kind of people showed up. [Shackleton’s ad basically said that members of his expedition would die and never be heard from again.] The point being, I think, to see if there were people out there who wanted more from life than was part of the ordinary.

JA: What was the reaction?

RB: After vetting, the question was raised about how to do this without misleading people.

JA: Yeah.

RB: But it’s an interesting question.

JA: It is.

RB: And then recently, the idea of living an authentic life came up. This was in a talk I had with Jennifer Boylan, who had spent most of her life as a man. So what really was at the root of her concerns was the notion of living authentically. We talked about whether it was part of public conversation.

JA: No, it’s not.

RB: Once you’re pegged as a war correspondent it must be necessary to attach all the myths and such.

JA: People like to pigeonhole other people. Because so many people, I think—[pauses] it makes life easier. People at a certain age tend to reconcile to certain realities. They tend to truncate their own ambitions. I never quite gave up that wish list [from] being a kid.

RB: [chuckles]

JA: The kind of hyper-reality that I found and encountered—

RB:—and still encounter.

JA: And still encounter. Well, that was what I was going to say. It became an ineludible touchstone. I’ve been through a whole evolution—I remember in that period in the ‘80s when I was going to war a lot I would come back to the States after living in El Salvador and feel completely disassociated. I didn’t have the ability, the other seasoning necessary to find an equilibrium. And I stopped talking about what I did. And I lived in a kind of disassociated state. Head and heart were divorced.

You pick up the cultural nuances in a place. If you are in a Muslim country, you should know before you go there, that when you sit down in your host’s home you never show him the sole of your foot. Well, Americans always show the sole of their feet, if you know what I mean.

RB: Wait a minute, are you suggesting that once having seen El Salvador and Guatemala and Nicaragua and the, uh, anomalies, you should have been able to adjust to objective conditions in the U.S.?

JA: I’m not sure.

RB: That was a failing of yours?

JA: [chuckles] Well, because what I was living, arguably, was such a singular experience compared to the kind of collective. I couldn’t expect people to understand my life. I found that people, they would ask me, “So how was it, Jon Lee?” But I could see in their eyes with the exception of a handful of friends or family that really wanted to know, that it was a kind of perfunctory question and they wanted to hear something racy or that they had already imagined because of the kind of interjections they’d make. “So was it this? Was it that?” I could see even before I finished the first story that was all they wanted to hear. And in most cases I finally found comfort in the fact that in the end people just wanted me back. And they wanted me back as their friend. Whom they knew as a companion who had nothing to do with that life that I was living. And I realized that I could find peace with it, if I just fell into their lives. You know what I mean?

RB: Yeah.

JA: And sat with them and was a fly on the wall for the things that they did. Because they had all of these rituals. Whether it was talking about literature or a certain bar they went to or baseball or the family. Actually, it was a great comfort just to efface myself. But as a result you live compartmentalized. It’s not a bad thing.

RB: No, right.

JA: As long as you become conscious of it. It’s not a bad thing.

RB: As long as you don’t feel compromised.

JA: And in my writing I am able to bridge that somehow, I think.

RB: That was on my mind. You see that people aren’t concerned or are disinterested in the story but you want to write the story for somebody—

JA: There are people—I have found in more recent years—I have finally found that there is an audience. And I don’t always meet them. But they are out there. I probably am a bit bullheaded because I am the American who has always lived abroad. So I am condemned to have one foot in this country and one foot abroad. And what I mean by that is I am doomed to be an American while I am abroad and take it on the nose for being a Yank, and believe me it’s getting harder all the time. And I can’t help but see Americans as foreigners, too. And so I guess part of me feels like a mediator, almost. Or maybe that’s entered in the way I behave and the way I perceive and the way I write. I am always trying to explain the rest of the world to the Americans. I am trying to show Americans how our shadow falls. So often we don’t—here’s an anecdote. [pauses] You pick up the cultural nuances in a place. If you are in a Muslim country, you should know before you go there, that when you sit down in your host’s home you never show him the sole of your foot. Well, Americans always show the sole of their feet, if you know what I mean.

RB: [laughs]

JA: Always speak too loudly and always—I’m talking allegorically as well. It’s both. So I have always squirmed at that. And just want them to understand it. And I guess in a larger sense I’m so aware because I have lived in the third world before this current business in Iraq. These countries where we have had such a tremendous impact and which are just completely consigned to the dustbin of history. And where we continue to have huge impact. I want people here to be aware that we really have affected those places. And that we should acknowledge them and keep them present. It’s more of an intuitive pilgrimage than anything else—a sense that we must keep our history palpable and visible and present.

RB: My own conventional wisdom is that Americans clearly don’t care about the rest of the world, barely care about their own history, for whatever reasons and whatever distractions. So these lessons—if Americans are sold that bill of goods that they are good and everyone else is bad, there is no reason to care. Last year I spoke to two writers who has been in Nicaragua in the ‘80s (Joseph O’Connor and Marcelle Clements) and when we got around to talking about it we were all recalling how much we loved the place and the people.

JA: Yeah.

RB: And having this feeling of sorrow about what had been done. And acknowledging that their time has come and gone. Nobody cares now. About what was promised them, the monies to rebuild.

JA: No one. Central America has become—it was extremely violated in the ‘80s. [And] in shoring up the people we wanted in power to fight “communism,” and in order to undermine left-wing governments, we violated the very fragile fabric of those societies. And in the years since then Central America has become one of the black holes on earth. In a sense. Yes, tourists go to Costa Rica. But El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, these are place where there is a gang culture arguably more viscous than anything we have seen here—a direct export of our culture. A huge drug problem.

RB: Young kids?

JA: Yes, and armed. More people die in El Salvador now than died during the civil war. And many of the former guerrillas or guys in the army have gone into these gangs. And we have turned our back on it. So we create these kind of no-go areas. And it is a useful reminder—remember Sept. 11, how then began the kind of hand-wringing debate of, “Oh, we turned our back on Afghanistan after we got rid of the Soviets by helping the mujahedeen,” And, of course Osama bin Laden was one of those guys. If you leave a place suppurating like a sore, for years, it’s going to come back and it’s going to infect you.

RB: It seems that when that line was taken there is the mistaken impression that an equivalence is being touted.

JA: No, not at all. My point is this: How much did we spend in El Salvador? Let’s say it’s a small sum compared to the things being bandied around today. Let’s just say it was three billion dollars. I don’t know the figure that we have poured into El Salvador since but I can guarantee you that if we spent three billion dollars in fighting communism, we have spent perhaps a tenth of that in social programs. Even in terms of naked self-interest. Let’s say we wanted to be the most calculating imperial power. Why not invest in convincing the people that we are a benign power?

RB: Why not?

JA: Why not? I don’t know.

RB: [both laugh]

JA: I don’t know. It is very short-sighted. Maybe it has to do with our seasonal political system. Or that we are an entertainment culture now. People spend most of their lives—their imaginations are taken up with imagery and recreation and various kinds of self-indulgence.

RB: Setting aside the masses who seem to have become transfixed by all this, there is still an elite, a mandarin class, an intelligentsia who slip in and out of government and policy circles and academia, those people have an awareness, have insight. Is it all neo-conservatives who are participating in the debate and policy formulation?

JA: No. Not entirely.

RB: No countervailing forces?

JA: Yes, there are, you made me think of a friend of mine. Actually she just quit government. To go to work for George Soros to do good things. She is a do-gooder. She wants to be a do-gooder. She is one of those people that went into government believing—she is a good American. One of the best Americans I have ever met in government. But by God, I have never met another one.

RB: [laughs]

JA: Not to that degree. And boy she is a worth a thousand of all the other ones I have ever met.

RB: What about Peter Kornbluth at the National Security Archives?

JA: He’s kind of crusader. We have plenty of people. That’s where the balance comes in. And they have an effect. Their actions because they incur so heavily into the public domain and they create an impact in the media and public opinion, they do effect things. And well, they—I’m thinking of Sy Hersh, too.

RB: They aggravate people. Richard Perle threatened to sue him in England.

JA: Yeah. OK, but Americans can no longer torture people in Abu Ghraib. OK, they are turning their backs and their Iraqi hirelings are, but at least our people aren’t. In small ways, people can amend the behavior of this kind of juggernaut we have.

RB: In talking to Samantha Power she was unabashed about wanting to have her book influence policy. She wins a Pulitzer and is on a lot of talk shows and so on. The next genocide that comes along, what happens? Much public hand wringing, and permission to use the word “genocide”—”Yeah, that’s genocide.”

JA: We’re talking about Sudan now? Yeah. Well, hmm, but [pause] I don’t know substantively what’s being done to stop it. But at least there is this kind of swarming, hand-wringing behavior. Eight-hundred thousand people haven’t been killed. In the summer of 1994, everybody just ignored it [Rwanda]. It’s extraordinary. If that hadn’t happened over Rwanda we wouldn’t have this behavior, this very public—even this debate taking place over Sudan. Unfortunately, [just] as many people’s lives are at stake, potentially, but it’s a different kind of emergency. The actual number of people being murdered or killed is smaller; the real danger is from the starvation, the epidemic. But action is being taken. However, there are all kinds of political connotations and to a certain extent it is being characterized in Africa and in the Arab world as a part of the war on terror. It’s part of the Christian crusade against Muslims. So it’s an awkward kind of thing. I try not to be overly cynical about this and I commend people like Samantha Power for trying to enter into policy and make these things, to keep them at the forefront of our consciousness.

They were all worried about this notion, the fact that there had been no American announcement on our ultimate intentions in the country, understandably they were worried that we intended—that we had ulterior motives for being there. That it wasn’t just knocking out Saddam. That it had to do with oil, it had to do with this neo-conservative Pax Americana ambition.

RB: In The Fall of Baghdad, the first four or five chapters bring out a sense of the conditions and culture in Iraq and that it wouldn’t have taken any great effort for any intelligence-gathering to understand that our incursion into the country was not going to be greeted with music and flowers.

JA: I know. I don’t know where they were.

RB: You didn’t do anything more complicated than talk to people.

JA: That’s right.

RB: And it was present in every conversation.

JA: Yeah. Every conversation. Everyone was worried about it. Even the people that had suffered terribly at Saddam’s hands. For the Shia in Iran, they were arguing still, at that late date, we are talking January 2003, by the time I was there. They were trying to convince the Bush administration to use all that muscle they were putting into the push for war into the U.N., into putting teeth into the sanctions, into forcing Saddam into so undressing himself in public, that he fell off the vine. On the assumption that no ruler can possibly sustain that kind of ridicule and exposure and indignity for too long. And they pointed out that they had forged alliances across ethnic lines—Sunni, Shia, Kurd, Turkoman—and had a plan for an Iraq transitional government in which American troops would not be needed. And of course they were forced into a pragmatic alliance with the Americans because the Americans were going to come anyway. And they stood to gain power if America made good on its word and held democratic elections; as the democratic plurality in the country, they would win. But it hasn’t turned out that way, yet. And they were all worried about this notion, the fact that there had been no American announcement on our ultimate intentions in the country, understandably they were worried that we intended—that we had ulterior motives for being there. That it wasn’t just knocking out Saddam. That it had to do with oil, it had to do with this neo-conservative Pax Americana ambition.

RB: Or worse.

JA: Or worse, yes. It niggled [at] and bothered a lot of people. And people were warning me. I remember this Shia cleric and he was echoed by a secular Sunni exile in Jordan and this was a Shia cleric in Iran and they both said almost verbatim the same thing: “This war is happening. OK, if you Americans come, come, do it quickly and leave. Don’t get caught in the shifting sands of Iraq. The Iraqi are very nice people but they do not like foreign occupation. They will fight. It will be a big mistake for America and bad for all of us.” [snorts]

RB: I just read an interesting movie review by Jim Shepard in the Believer magazine of David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia and Herzog’s Aguirre: The Wrath of God and Bush-Iraq policy. These movies are about obsession in the face of a different reality—one more reason to see Lawrence again. How is it that [Iraqi exile Ahmed] Chalabi became the seemingly infallible source of information about Iraq in Washington? Because he was in Washington?

JA: The intricacies of his relationships are beyond me. I was less focused on the exile story than the Iraqi story in the run-up to the war. But I have gotten to know him a little bit since he has been back in Iraq. To a large extent, you could say Chalabi was successful. He hammered away in Washington, built up relationships, became this indispensable figure. You know he was an Iraqi that an American could like. And hang out with. He is a brilliant guy. He went to MIT. He’s got a sense of humor. He is urbane. He’s rich. He speaks excellent English. He reads novels. I mean he is a polymath type. You have lunch with Chalabi, and it ranges from a literary critique of Lolita in Teheran to a dissertation by him on the ins and outs of cryptography. He is a very compelling charismatic figure, and I can see him taking Washington by storm. He was very convincing and he almost single-handedly drove this thing. So he got rid of Saddam, you could say. He got the Americans to get rid of Saddam. He did what it took including, perhaps, concocting evidence.

RB: Might he be compared to [now deceased, Miami-based Cuban exile] Jorge Mas Canosa?

JA: To an extent, yeah. Except Mas Canosa wasn’t successful.

RB: And Mas Canosa is dead. [both laugh] If you live long enough you have a shot at accomplishing what you want. It appears the only person who remains a defender of Chalabi is Christopher Hitchens. He will periodically reify his support of Chalabi or castigate others for attacking him without evidence.

JA: I don’t know enough about Chalabi’s past. So much has been written. In the scheme of things now, if you look at the array of political figures in Iraq, Chalabi is not necessarily a pernicious character. There is a wide range of people there. He has actually built very successful relations with Shia clergy, which is quite surprising considering he was regarded as the CIA’s man and as a guy who had not been in Iraq since the ‘50s, the ultimate exile. Of course, people despise him. I remember there was a period in Iraq we would comment to each other, “My God,” and I even said this the first time I met him: “You definitely surpass Saddam as the most hated man in this country.” And he actually flinched. He was quite wounded by that.

RB: Meaning he was not aware of that? He had suppressed it? He was surprised?

JA: I don’t know, maybe he is more sensitive than he seemed. He seems kind of thick-skinned. But he may not be. He has a bit of a Cheney face, if you know what I mean. He has a kind of permanent sneer that may just be his physiognomy. In the case of Cheney, I think it is probably his soul. I am probably sounding like I have a soft spot for Chalabi. I suppose I do, in a way. Just because he is such a character and I can’t help but enjoy a character like that. But Hitchens, I have real problems with now. [pauses] OK, he is an agent provocateur and he is a wonderful polemicist and he is a brilliant guy, but I think he is so wrong-headed about this. This insistence on reaffirming the various supposed justifications for the war on the basis that Saddam was evil. And ignoring what is happening now. He is almost arguing in the face of what’s happening now.

RB: But it’s really his hatred of totalitarian Islamic fundamentalism and it goes back to the fatwa against his very good friend Rushdie.

JA: Yes, but we are not, with Saddam, arguing about totalitarian Islam—yes the state was totalitarian. But there is a definite schism between what was Saddam’s Iraq and what is Zarqawi’s imaginary Iraq or bin Laden’s imaginary Muslim homeland. Or the Taliban-held Afghanistan. And this is key and this is not a defense of Saddam’s Iraq—I was so happy when he was overthrown. And I was naturally very torn up about that the fact that this war coming within the rubric of the war on terror, somehow the wrong time. Why didn’t we do it before? It was problematic in so many ways. And it has proved to be.

RB: Too many inconsistencies, yeah. The argument seems to boil down to, “It’s right because we have faith that it’s right; therefore; it’s right”—obviously a circular argument.

JA: We’re going to prevail. They are bad, we are right. Yeah.

RB: In talking about Samantha Power’s The Problem from Hell, I stated her ambition to affect policy. Beyond telling the Afghan story [In A Lion’s Grave] and the Iraqi story, have you any such interest?

JA: Hmm. Well, one tries to be fair-minded. There is nothing such as real objectivity, I guess. Well, they are different books, of course. Lion’s Grave is an anthology of my pieces with one new written forward with an intersticing of the e-mail correspondence between myself and my editor. It was both an attempt to give a moving portrait to the beginning of the war on terror in Afghanistan and to try to bring people into that landscape as it moved. And as it was. And to give a sense of history and of time and place and introduce people as people, to them. And also both an eye and an ear to showing how journalists move on those landscapes. So many people ask those questions—I think people find that kind of interesting. So The Fall of Baghdad is different because it’s a single narrative. I unraveled my pieces and I wrote a lot more. And it’s an attempt to—I mean I had no pretension other than presenting a faithful document that was readable about the fall of a city, which is an archetypal event. And I was aware that I had been a witness to one. And I wanted to render it. And in the same way a painter might decide who has been doing watercolor—decides to take on oils and move from portraits to miniatures. Or still life, to do still life for the first time. It was kind of an intellectual challenge. And it was history. History now. And I was very aware as I wrote it that it was history that had a great deal of importance now. And that in the small moments that I saw lie the seeds to many of the larger issues. So it’s a portrait of the country as it was under Saddam in the final years of his regime, and final days and months. And it’s fused with that inevitability of the American war coming and its aftermath. And I chose to—I didn’t seek out people who speak worriedly about the coming of the Americans. These are the people that I met. This is what I heard. I am aware this is very polemical and happens to coincide with this election. I have strong views of what has happened in Iraq and in fact they coincide with one side in this political debate but as opposed to say, Samantha Power, I don’t feel comfortable with the role of pundit or political activist so much as I would hope—I guess I speak in my readings and things more bluntly than I write in the book. But I think people here—I wanted to have measured tone that was as objective as I could make it, that lays it out as I saw it—because that’s how I approached Iraq. I wanted to find out the truth about what Iraq was like and I have tried to follow the progress of the American enterprise in Iraq in the same way. I would hope that because it’s so polarized people would find my voice or my narrative fair-minded and therefore perhaps easy to draw conclusions from, rather than appearing to come from one side or another of the political spectrum, as so many books are nowadays. They are very pamphleteering and I wanted to outlast this moment, too. So, it’s a story. It’s a story of people’s lives. And the stories of Iraqis, in Iraq.

We have to tell the Iraqis, it needs to be reinforced the message that Senator Kerry floated in the first debate, that we have no ultimate [ulterior] intentions in Iraq and will leave the country. But it needs to be reinforced. It’s very important to deflate the insurgency. That’s one of the reasons it’s so powerful. There is apparently no end in sight.

RB: I will assume that at least for a brief moment this book will be mediated for most people by reviewers and pundits—perhaps one person in 20 who knows of it will have read it—so has anyone disputed your report in whole or parts?

JA: Since I have been—I don’t know exactly. It’s still early. It’s only been out for 10 days. I have been on some of the mainstream TV things. Most people seem to be pointing out that it’s the story of Iraqis and a lot of people are asking me or have noticed what you pointed out, that the keys to many of the mistakes are there and people’s perceptions that were captured before the war. Many people asked me what I think the solution is. They are worried that Iraqis are completely embittered by us now. I still think there is room to maneuver. I don’t know that that’s happened yet. It would be interesting if they did. I was surprised. I was asked to go on Fox.

RB: Which program?

JA: Fox & Friends, one of these morning shows. And I didn’t know what to expect. In fact, I was on right after Henry Kissinger, who I bumped into in the green room. [laughs] It was interesting.

RB: I’m sure.

JA: And he said [with moderately accurate imitation of the infamous war criminal, “I must read the book. It looks interesting.” I wasn’t sure whether to mention Chile or not. Anyway it was too early in the morning, so I just said hello. The [Fox] guy asked me, right off the bat—I thought he would control it, it was one of those wham-bam interviews, I thought he would control in a way that I wouldn’t be able to say anything. He said, “Did we make mistakes?” And I had my chance to say, “Yes, we did.” “Is there any hope?” And I had my chance to throw in a little bit there. So to a certain extent it is happening, I guess.

RB: What about Richard Holbrooke, Kerry’s foreign policy adviser, reading the book?

JA: To be honest, I would be honored, because I do agree that we need a change of leadership as a result of the disaster in Iraq. I don’t have any faith that the Bush administration can switch gears now. Even if it wanted to. They’ve completely squandered their opportunity. And I did speak at the Council on Foreign Relations with a lot of types like that there. I find myself feeling the importance of speaking out on the issues and what I see as the problems but also what I see as the possible solutions. And it all comes down to the same thing: They’re beyond my wherewithal to deal with specifically, but what I am saying is, it needs deft leadership, someone who is very sophisticated at juggling all kinds of people. which includes the American military, estranged European allies, Middle Eastern governments. There is so much at stake now. So much about it is in the way we speak. And these messages one sends. We have to tell the Iraqis, it needs to be reinforced the message that Senator Kerry floated in the first debate, that we have no ultimate [ulterior] intentions in Iraq and will leave the country. But it needs to be reinforced. It’s very important to deflate the insurgency. That’s one of the reasons it’s so powerful. There is apparently no end in sight.

If the country becomes so powerful in people’s minds and the behavior is replicated and goes on, i.e. warring here, warring there, the leader of the country becomes the personification of the nationality.

RB: Our idea of ending the insurgency apparently is to kill all the insurgents.

JA: There are people, sadly, that have to be killed, at this point. But there are also people who are looking for a way out. But we need to give them a way out by telling them we are not planning to occupy their country. And that never been said.

RB: It’s amazing that Paul Bremer now comes out and says we didn’t have enough troops [in Iraq]. [By the end of the week of the interview, he seemed to recant that.]

JA: His timing is curious, which is true. But then he also disbanded the army and banned the Ba’ath Party, which gave heart to the insurgency.

RB: He is a former employee of Kissinger Associates?

JA: I gather he was and he was a counter-terrorism adviser to Reagan. Or maybe the first President Bush. But he is a piece of work.

RB: When I spoke to Anne Garrels last summer (2003) she felt that his appointment was a hopeful one and that he had a very good reputation.

JA: Before Iraq.

RB: She was optimistic and thought he would be able to get things done.

JA: I was very dismayed. I had a long interview with him in August of 2003 and I came out deeply discouraged and convinced that the thing was going to get worse. I don’t say that with hindsight. I found him very arrogant and completely incurious and really testy. He never asked me one question. And that’s not because I think I have so much to share, but relative to his position I did. I was someone who had been in Iraq, moving around outside. He was inside the Green Zone and only going out with these Black Hawk helicopters with Blackwater contractors, armed guys, going everywhere. When I pointed out things to him like, “You know, Iraqis are saying this or that,” expressing some kind of unconformity with the occupation, he’d get very testy and he’d say, “I don’t know what kind of Iraqis you are talking to, but nobody I meet says that.”

RB: Oh, my.

JA: I said, “When are we going to see civil society here? Until now most Iraqis have only had soldiers to deal with. When are people like yourself and myself out there?” He says, “What are you talking about? They’re all over the country.” And I was thinking to myself, “No, they are not. The only ones I have seen to date were these guys who looked like a cross between Lawrence of Arabia and Schwarzenegger, roaring around in unmarked SUVs with headdresses and guns poking out the window and Ray-bans and little headphones.”

RB: [chuckles]

JA: I never saw any of the other ones. We inhabit two different worlds. I inhabited Iraq. He inhabited the Green Zone. And I felt that was a serious error, a big mistake, and his tenure in Iraq just compounded it further.

RB: What explains the inability of seemingly legitimate information and intelligence to penetrate into this administration as well as the rest of the country? Other than the fact that Americans naturally abhor their children dying in Iraq, there is no sense that we have a far-reaching disaster on our hands—with long-range and destabilizing repercussions.

JA: There is a lack of awareness of this huge ripple effect. It’s becoming a whirlpool. I came of age in the Vietnam and the era of civil rights and I remember how divided the country was and I also lived abroad as a child and as a young guy. And I remember the angry attitudes about Vietnam. But you knew there was also a kind of recognition that there were especially young Americans who were trying to change things. There was a recognition that there were types of Americans. And now there is an anti-Americanism and an anti-Westernism which is rabid, it’s visceral. It’s deep and very often gratuitous. And it’s very widespread and transcends the Muslim world and it has everything to do with our behavior and the language that has come out of the White House since this whole business began.

RB: Really? Didn’t your experience in Central America and Cuba lead you to see that people always separated the government from the people? People would say, “Why is Reagan doing this to us?”

JA: Eventually one’s leadership—if the country becomes so powerful in people’s minds and the behavior is replicated and goes on, i.e. warring here, warring there, the leader of the country becomes the personification of the nationality. And that is what happens when Bush swaggers around, showing an incuriosity and inherent racism towards most of the rest of the world and certainly the Muslim world. When he uses words like “crusade,” and you know he is a born-again Christian. However he and his spin doctors amend what he says later, you know that the real feeling is—and when how homeland security and other parts of government are implementing policies which are now exclusory, invasive discriminatory, it’s sending a very strong message around the world, and even our European cousins and allies feel very estranged from us. And of course there is always a residual but bearable kind of anti-Americanism there that is usually expended in jokes or whatever. Now it’s pretty gratuitous. They take swipes at us for everything. Americans are easy to hate now. And it’s kind of excruciating to be one. And I do blame that on George Bush. And Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney.

RB: And Paul Wolfowitz.

JA: I do blame it on them. They seem not to care. And I don’t see it as a permanent situation—it can be amended. All we have to do is remember how the world reacted after Sept. 11. We had the goodwill of so many people. Even through the Afghan war. This war is what really did it.

RB: Afghanistan, I have read and it was confirmed in speaking with Saira Shah, an amazing woman, is slipping back into darkness, despite this current electoral hoo-ha.

JA: Again, there was never any real serious effort put into—on the one hand there were never enough troops on the ground to chase the remnants, they were allowed to reorganize, there was this kind of uneasy alliance struck with Pakistan which continues, part of the state continues to harbor them. There are these bandit lands all around and a complete lack of troops on the ground and so reconstruction—it would have been so easy to turn that country into a little jewel box. It had tiny, slender glimmerings of modernity in the early ‘70s before all the problems started there. It had a little ribbon of roads that connected all of its cities. It had some dams. It had some newly irrigated farmlands and agricultural research centers and new universities built here and there. It had all of that. But it was all destroyed. By the time we arrived there, in 2001, the highway between, let’s say, Jalalabad and Kabul—which takes you to Pakistan basically at the foot of the Khyber Pass. It’s 80 miles. The cement on it was completely gone. You might as well have been traveling in 1847. It took me eight hours to go on that road. It was gone. It was as though it had never been there. It had reverted 150 years.

RB: Not because of the poor quality of the concrete.

JA: It was because of the war. And it would have taken us what to rebuild that country’s roads? What do roads mean? The flow of ideas, the flow of commerce, employing the locals, weaning them away from the militias by getting them to build the roads. We have completed one, finally, belatedly, because people started criticizing the fact that we hadn’t done anything. Meanwhile, the Taliban have moved into the void. It’s one country where we have no real interests. We could put in—what would it cost us, five billion dollars? Do you know what that would be in that country? To leave that country like a gift. And just say, “Look, we really don’t have an interest. We just want to make it right. We are sorry for what we did in this country. And we are sorry we had to come back and make war because of the Frankenstein we helped create.”

RB: Jon Lee! An American administration is going to say, “We’re sorry?”

JA: It’s essential that we do. It’s so important, “And we are going to do this and now we are leaving. Please look after it. And we hope we have good relations.” Do you know the message that would send to all of the neighbors and to all of the Muslim world and all of the cynics, like you and me and everybody else who says, “Oh, the Americans never do that. They make the war and then they leave. They forget about you. They betray their friends.” Just once, just once let’s break the mold. We could have done it. [long pause] We still could.

RB: Yeah.

JA: I must sound like such a craven idealist? Afghanistan brings it out in me. I don’t know why. I can’t say that Iraq does. It’s more complex.

RB: So what’s next for you? The Iraq story is not over.

JA: No, it’s not over and I still write for the New Yorker—it’s getting very difficult to report. So I have to assess at the end of this month what it seems I can viably do. If I can continue to write on Iraq I will. But I am also going to begin include bringing the rest of the world again in what I do.

RB: I wish you’d go back to Central America.

JA: Well, I am also thinking of that, yeah. I need Latin America.

RB: What is the valence of writer versus reporter? Are you attending more to the refinement of your prose?

JA: More of a reporter than a writer or more a writer than a reporter?

RB: Certainly The Fall of Baghdad as you say is a more deliberately structured narrative, based on your columns for the New Yorker but not just a rehash—

JA: Well, I feel there is a whole world ahead for me in terms of honing my craft. I would love to try my hand at different topics—different kinds of writing.

RB: What about fiction?

JA: I don’t have any concrete ideas for fiction yet. But I look forward to having the time and the leisure to spend, to really craft some piece of writing. And maybe down the road. Probably my next book will be nonfiction as well. It will probably be Cuba. It’s not a repetition. It’s not a recycling. I wrote a biography [of Che Guevara] by intention, a very informational biography. Because I was dealing with such a mythologized subject. I tried to add detail and flesh and substance to his life. And I had to restrain from being more—

RB: Polemical?

JA: Yes, polemical. Again I was trying to lay it out as I saw it, the reality. But also I didn’t unleash my ever-present urge to be more descriptive in my writing. I love to write descriptively. There are certain things that I have this really strong urge to write I had to restrain myself because I was trying to deliver his life.

RB: Have you seen Paul Berman’s piece on the Motorcycle Diaries film?

JA: I thought he got a little hot and bothered. [chuckles] He felt a little strongly, a little too strongly. After all, Che in rhetoric—Che was fire and brimstone—the apocalypse cometh. But it didn’t happen. And in retrospect with Osama bin Laden—if you think about it. This man who wants to declare war on the great power. There are some odd and uncanny resonations. Che was no terrorist. He was a totalitarian, yes. But Paul has forgotten that there was a time, a crack in time in the ‘60s when almost anything seemed possible and a kind of utopian totalitarianism is somehow a logical outgrowth of the apocalypse of WWII and nuclear bombs and the threat that we all lived under that possibility of imminent elimination. And I am not trying to excuse Che.