Donkey Talk is a tri-monthly periodical or, as its back cover says, “a comprehensive ‘assyclopedia’ containing everything you would ever want or need to know about donkey ownership.” This is where you go if you want to find out how to keep that womanizing stud of a jack from mounting, biting, or “worrying the foo” out of the jennies. Tips on antibiotic resistance follow emergency preparedness checklists and tender reflections of livestock farm life. The magazine just published its 150th issue.

“The internet has been great for sales, as more people can find us,” says Mike Gross, founder and one half of Donkey Talk’s staff (the other half is his wife, Bonnie). The Cripple Creek, Colorado publication has subscribers as far as away as Luxembourg and New Zealand. “Just a small number cannot access [us] online, so we print a copy in-house.”

He means that in the most literal sense: After using PayPal to order the latest issue from their website, I received 34 double-sided pages connected by two staples in my mailbox. “When we first went online,” Mike says, “several hundred people insisted on getting print—that has now dwindled to less than one hundred.”

After the magazine’s small masthead and information on submitting ads, Donkey Talk commences its questions/comments section, which reads more like handwritten correspondences between bosom friends. “Are miniature donkeys safe around small children?” one concerned reader writes in. “I caught him today trying to stomp on one of the cats.” Mike advises one reader to take her mini gelding to the vet after she found blood in his urine. In her follow up, she assures that everything is fine. “I spread [powdered antibiotic] on bread and made him a sandwich with honey and molasses.”

Here is an excerpt from an essay titled “Donkey Psychobabble: Processing Life through Donkeys” by Marianne Smith, writer and trainer at Relax Your Ass Ranch in Gallatin, Tenn.:

Do donkeys mirror your life? Or do you see your life mirrored by your donkeys? The order doesn’t really matter. The important thing is we all have another avenue for some much needed self-examination. Donkeys can teach us to be better people. Said differently: Donkeys can find the better person that they already know we are.

The magazine ends with “cl-ass-ified” ads and a brochure for donkey-themed gift items: a fine bone china thimble, an embroidered canvas tote, gold parchment stationary, mailing labels, magnetic bookmarks, and a matte-finished mouse pad.

Mike Gross is not concerned about exhausting the material of this specialization. “We have new people getting involved with donkeys all the time.”

I was under the impression that I could walk into any news stand in New York and find a slew of oddly titled publications—something about ferrets or specially-authorized Bavarian buses—something effortlessly niche. But digging through piles of magazines in some of the city’s most well-equipped magazine purveyors, I mostly came across high art-ish titles that seemed too keenly aware of their presence in print.

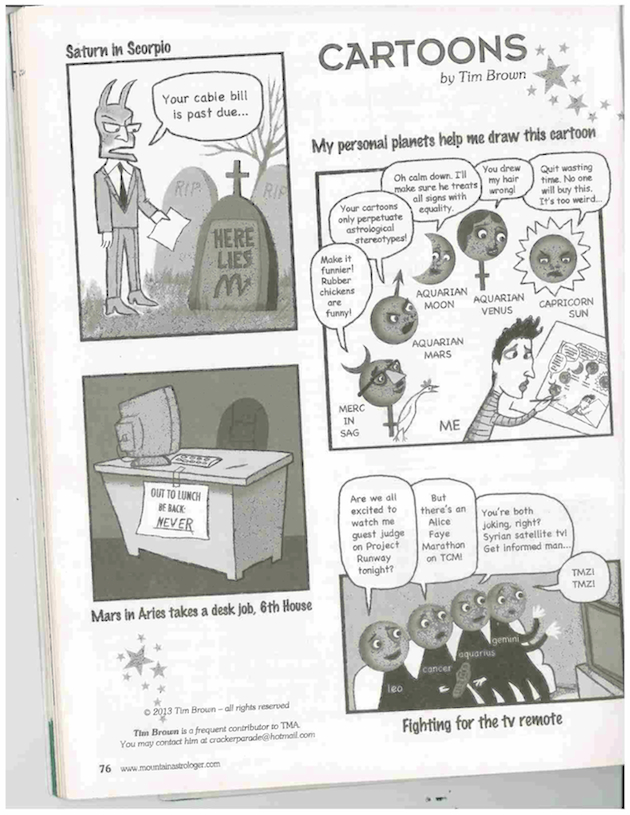

I resorted to internet research, sometimes lazily landing on BuzzFeed-esque lists of the “weirdest magazines ever.” This barely answered my questions, so I contacted the people involved, like Tim Brown from The Mountain Astrologer. Brown has contributed to the magazine—the only one in this article that I found in a shop—for 15 years.

“I analyze people’s behaviors and energies in the most objective way I can muster (Aquarius rising),” says cartoonist Tim Brown. “Amazed at the uncanny results.” In a cartoon in which Brown draws himself drawing a cartoon (the exact one we see on the magazine’s comic strip), his critical Aquarian Mars hovers above him: “Your cartoons only perpetuate astrological stereotypes!”

The Mountain Astrologer began as an 8-page newsletter in 1987; it currently has 8,400 subscribers and prints 16,050 magazines per bi-monthly issue (96,300 copies a year). The magazine often name-drops celebrities and public figures with little to no context. “Brando spoke to a waspish, neurotic writer whose natal Mercury in Virgo was exactly conjunct to his midheaven,” writes Frank C. Clifford of Truman Capote’s famous New Yorker interview with Marlon Brando in 1959, soon after he discusses the Frost/Nixon interviews and Whitney Houston’s divorce from Bobby Brown. Astrology is not limited to the charts of people; for example, Monsanto owes its circumnavigation of government rules to Pluto in Capricorn. Again lacking context, we are bestowed with a word of advice: Never give a Libra a helium balloon.

The Mountain Astrologer does not necessarily combat stereotypes. According to one “glyphoid,” there are three types of astrologers: “geocentric, heliocentric, just plain eccentric!” Readers need not refer to a glossary to discover the meanings of abbreviations (MC, SA, ASC, DSC, IC) or terms like 8th-house Chiron or trine. In this sense, The Mountain Astrologer does not lack context as much as it relies on familiarity. “Quincunx” is tossed around as casually as “email.”

“Prescribing words to any specific human energy is always tricky,” says Brown. Astrological lexicon has a strict—Taurean, if you will—firmness to it; it seems beyond dispute, try as you may. Astro-speak simply speeds up the conversation. Despite The Mountain Astrologer’s explanatory inclinations—“Whitney Houston divorced Bobby Brown when her solar arc Mars was conjunct to his natal Mars at 20º Scorpio”—its content is based on interpretation rather than dogma. In a regular column called “Transit Tales,” astrologer Dana Gerhardt offers other astrologers advice on how to “provide hope responsibly.” She challenges Ptolemy’s opinion that Mars and Saturn are malefic planets: “Given the wet clay of any one life, the planets are wholly unpredictable.”

Brown has similar views about the fertility of astrology’s raw material. “Astrology basically divides the entire scope of the human condition into twelve pieces,” he says. “How can you not have endless subject matter?”

“Are you afraid you’ll run out of jokes?” I ask.

“Every time!” Brown replies. But he manages to salvage inspiration from the quotidian dilemmas of his friends and coworkers. “Not having a lot of astrology cartoonists worldwide doesn’t hurt either.”

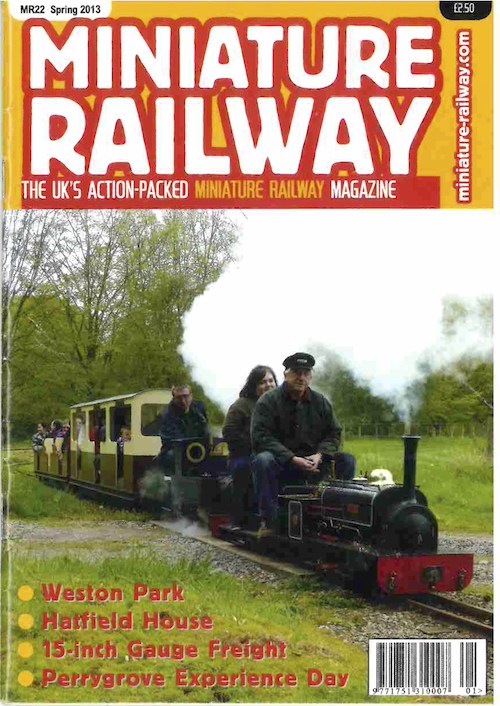

“How did you become interested in miniature railways?”

“I thought it was normal!” says David Henshaw, editor-in-chief of Dorchester, UK-based publication Miniature Railway.

I had heard of model trains, seen them in many a Christmas movie. I had been to transport museums that allow you to roam the carts of defunct railway models. But miniature trains such as the ones on the covers of Miniature Railway—pictures of adults riding trains that seem far too small for them—are new to me. They’re staples in children’s amusement parks, of course, but as a robust field of scholarly analysis and a roomy pocket of heritage engineering culture, I had no clue.

Miniature Railway is hardly nostalgic. Henshaw is in the midst of creating a comprehensive map of all the miniature railways in the United Kingdom. “We estimate there are 1000 in total, but many are private, known only to a small group of friends. I have agreed to only show 400.” Henshaw admits that “quite a few” of those 400 are private. In August, The Telegraph wrote a feature on the “irresistible” romantic allure of a garden steam train. Apparently a popular activity among enthusiasts is cooking bacon and eggs in a shovel over the burning coals of a miniature train’s engine.

“There are many miniature railway enthusiasts in Australia, Canada, the U.S., and Germany, and a few in India too,” Henshaw says. “Most other nationalities find the whole subject perplexing.”

Miniature Railway’s ads are what you might expect: miniature railway destination spots, model train expos, and a locomotive plates maker in Droitwich (“NOT the cheapest, PERHAPS the most expensive, PROBABLY the best.”) The articles are also what you might expect—fascinating to the miniature railway enthusiast, slightly Greek to the rest of us. In the magazine’s pictures, Caledonian blue–polished trains snake through tall-treed woods and people convivially gather near cobbled tracks.

I wouldn’t imagine the cozy ethos of this digest-sized publication would translate well into digital modes, and David Henshaw more or less agrees. “I suspect that most small publications will go digital within a few years, but Miniature Railway is one of the few that will not.” One of the merchandise items featured on the back cover includes a heavy-duty binder with gold embossed letters intended to hold print copies. “Our readership is older, more traditionally minded.” Henshaw does express concern that soon there will not be enough printers around to print at a reasonable price—the print run per issue, which comes out tri-annually, is 800 and costs $1,800 (yearly subscriptions are $12 a year domestically).

Henshaw calls the economics of paper dubious. “These are interesting days!”

“The different articles are designed by different designers, not related to any grief issue. However, when possible, we try to use a larger font size to make it easier for grievers, with tears, to read.”

Grief Digest, simply put, is a magazine for the bereaved, by the bereaved. Its covers display zoomed-in flowers, hot air balloons, and other doctor’s office–friendly motifs. An ornithological zookeeper loses an epileptic terrier, an award-winning local news anchor sees her daughter’s body wrapped in velvet, a lifelong Rockies fan is widowed twice in nine years.

I was unsure about how to approach the subject of grief without seeming maddeningly circumspect, so I abandoned sensitivity altogether. “Do you ever find your work depressing?”

“Sometimes, but there are rewarding moments in abundance as well.” This is founder and chief editor Janet Sieff. Sieff is also an executive director at the Centering Corporation in Omaha, the oldest grief resource center in the country, according to the company’s website. Grief Digest is its imprint.

“Many self-help books are just one person’s experiences and opinions about what is helpful,” Sieff says. The magazine’s editorial mission is to publish crowd-sourced content around grief. Each article has a title with a different font: some cursive, some blocky, and one, for an article titled “When Disaster Comes to Town,” in a spiky-edged Word Art typeface meant to imitate fire. Font size fluctuates from 10-point to 12-point. The pages are glossy. I like to think it is a style choice that mimes the vastly different ways each individual experiences grief. It’s not.

“The different articles are designed by different designers, not related to any grief issue,” Sieff confirms. “However, when possible, we try to use a larger font size to make it easier for grievers, with tears, to read.”

Grief Digest’s annual print run is between 10,000 to 12,000, with yearly print subscriptions costing $30. There is no online-exclusive subscription. A large portion of Grief Digest’s print run is ordered in bulk by churches, funeral homes, hospitals, and schools, who distribute it for free. “Some of our more seasoned readers prefer the touch or smell of a hard copy,” Sieff says, “and some prefer them as keepsakes. Support-group leaders keep them for arts and crafts.” Paper seems to give grief—and ultimately, consolation—a texture.

The magazine celebrates its 10th anniversary this year. In her time as a publisher, Sieff has not seen the definition of grief change as much as expand—the grief of losing a love one is often discussed alongside the grief of deployment, job loss, financial stress, bankruptcy, and relocation.

“I have also seen grief change though the social media sites, such as Facebook, Twitter, and online memorials,” Sieff says. “A young man in Omaha stated that seeing his grandmother on Facebook, after her death, was creepy.”

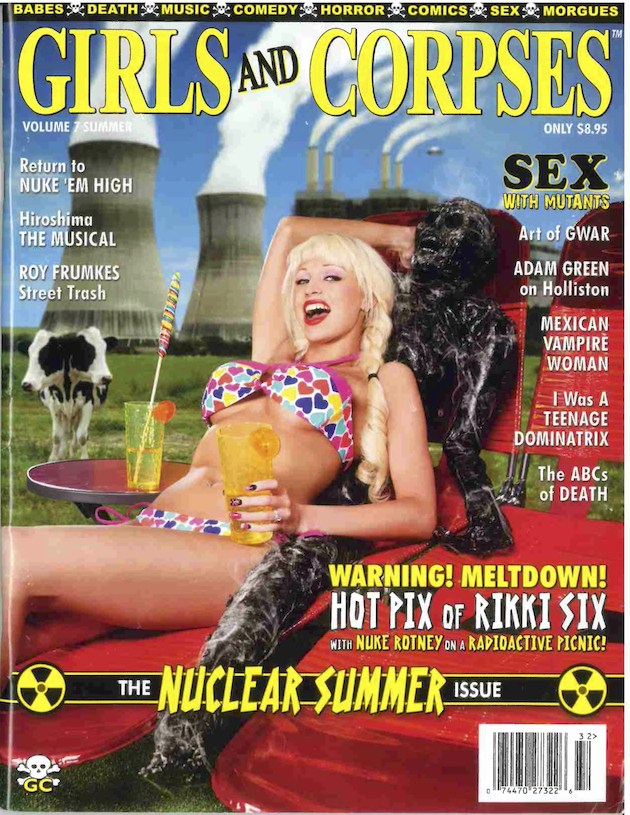

Girls and Corpses, a quarterly, exhibits Playboy-primed models in compromising positions with rotting corpses. The corpses are not actual corpses, though founder and editor-in-chief Robert Rhine tells me that there is at least one real corpse in every issue. When asked where he gets his corpses, he writes: “The bodies are donated to us in various ways, often before death, from all over the world. Sometimes the person themselves donate their body and other times their families donate their deceased family member. We have so many people who want to be dead in the magazine that we currently have a backlog of over 100 bodies and are currently unable to take on any more corpse models.”

Just in case you were considering it.

The issue I ordered includes “hot pix of Rikki Six” with a corpse named “Nuke Rotney” on a picnic outside a nuclear power plant. The tone is overcast with humor, but there are moments of poignant tragedy. For example, in an interview with Rob Depew, a “restorative artist” who specializes in embalming corpses that are particularly ugly, one of the bodies he had to “clean up” was that of a man who died with his face in a pot of boiling chili. Another was that of a 10-month-old child-abuse victim whose skull had been smashed on the corner of a table. “Performing a restoration on a barely developed skull is hard, technically and emotionally,” Depew says.

“I thought about combining two extreme things, girls and corpses, into a literary Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup,” says Rhine. “Humor is how we deal with tragedy. We have letters from readers who say they were afraid of death and the magazine has helped them.”

But not all the letters are positive:

“You people are FUCKED IN THE HEAD!”

“I can’t believe there is a magazine called Girls and Corpses! I saw it on the newsstand next to Barbie magazine of all things!”

Rhine seems to love the outrage. He willingly shares with me the worst of his hate mail from the magazine’s “Letter to the Dead-itor” section. Other sections include reviews of movies and video games, comic strips, and more interviews with ex-dominatrices, current vampire embodiments (“El Vampiro Mujer de Mexico”), and horror film directors. Needless to say, most of the images are painfully graphic.

The magazine does not operate without tongue-in-cheek moments. “You can put a beautiful woman next to anything and it will sell,” the writer, actor, director, and ex-CNN employee says of his publication. “We could have called it Girls and Eggplants and done pretty well.”