CrazyBike

New York's new bicycle-share program is a big success. Since May, bikers have taken 646,000 trips. But the initiative has also caused many rational people to explode with rage. Why? Because humans are hardwired to hate cheaters.

Since its launch at the end of May, New York City’s bike share system has prompted an artist to threaten sacrificial suicide, a community activist to compare a city agency to the Taliban, and a Pulitzer Prize–winning member of the Wall Street Journal editorial board to proclaim that “the bike lobby is an all-powerful enterprise.”

As of June 30, 2013, the Citi Bike program—comprised of 6,000 short-term rental bicycles spread across 300 self-serve stations in Manhattan and a small wedge of Brooklyn—has also seen some 646,000 trips accounting for about 1,535,000 miles traveled. It has attracted 52,000 annual members willing to pay $95 a year for the privilege of taking a 50-pound, Citibank-branded, blue bicycle from a kiosk, pedaling it around for a fraction of an hour, and returning it to another kiosk.

If that doesn’t seem like cause for seppuku, then you’re not alone.

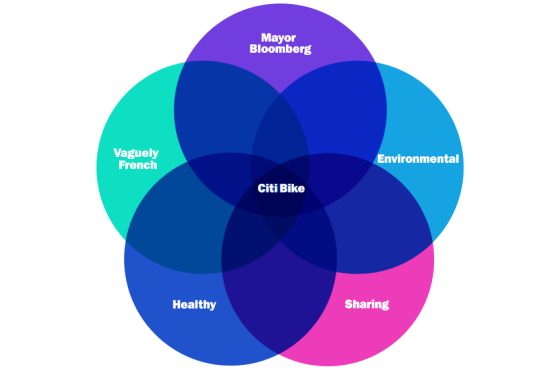

In the days and weeks after Citi Bike’s most frothing critics said some truly bat-shit stuff, pundits, bloggers, transportation advocates, and even Jon Stewart on the Daily Show took turns and great pleasure in theorizing why people—conservatives in particular—could hate it so much. New York magazine’s Dan Amira summarized it all wonderfully with a Venn diagram.

Amira explained, “In a way, the depth of conservative animosity for a bike-share program makes perfect sense. Because, as the Venn diagram above indicates, Citi Bike finds itself at the very nexus of five different things that conservatives hate.”

Indeed.

But there’s another force at play far more primordial than ideology, and it does a better job accounting for the breadth and fury and strangeness of the critics’ comments: Citi Bike is a way of cheating the system, and humans are hardwired to defend against cheaters.

Citi Bike is relatively cheap, convenient, and quick. (Full disclosure: I was hired to do some writing for their website around its launch, but no longer have a relationship with the program or its parent company). It combines some of the benefits of biking (fun), walking (convenience), driving (speed), and mass transit (cheap), but very few of their hassles and consequences (storage, ownership costs, traffic, etc.). In other words, it’s cheating because it’s an appealing way to circumvent established patterns, and it’s not yet available to everybody. Most importantly, it’s new and not yet normalized.

For now, some New Yorkers can get around in a novel fashion that not everyone is ready or able to attempt—and yet everyone must accommodate those who do. That imbalance has bred resentment, just as it did in London and in Paris and in Washington, DC, where charges of impropriety, predictions of imminent failure, and the certainty of widespread slaughter in the streets found space in the opinion pages after their respective programs launched. In all of those cities, and the other 372 around the world that have bike-sharing programs, the complaints quieted down. They will in New York, too, but the program’s critics are expressing a powerful feeling right now. One that makes every blue bicycle and Citi Bike kiosk an affront to the way things ought to be; a low-down, no-good cheater’s way of getting around.

People really don’t like cheating. From the Ten Commandments to playground rules to Hammurabi’s code, fairness and propriety have long been expected in interactions, as have reprisals for transgressions. From the 1960s on, academics frequently turned their attention to the topic. William Bowers of Columbia University did a landmark 1964 study of scholastic dishonesty, concluding that 75 percent of the 5,000 college students surveyed had cheated at least once. The National Science Foundation’s General Social Survey has included married couples since 1972, in an effort to identify the frequency and causes of matrimonial infidelity. More recently, there has been a turn toward understanding the evolutionary rationale behind cheating, as well as the social impulse to punish it. In 2002, a pair of Swiss researchers published a groundbreaking paper titled “Altruistic punishment in humans” in the journal Nature. It—and dozens of the more than two thousand scholarly works that have followed it in the past decade—offers compelling evidence that humans will seek to punish cheating even if that punitive urge is personally detrimental and offers no immediate benefit.

In the study, participants were given monetary units to play a series of games that required players to pool their individual resources. The more money pooled, the better the outcome for the entire group, though it was always possible for an individual player to put in less than the other participants and still receive an equal share of the outcome at the end of the game.

At the close of each round, players were informed of their cohort’s investment decisions. In some rounds, they were allowed to penalize those who contributed less but took a similar share. In other rounds, that wasn’t an option.

Punishment doesn’t need to fit the crime as much as it needs to happen in some form.

Very quickly, two trends appeared. The first was that people like to punish cheats: 84 percent did it at least once, 34 percent did it five times or more, and nearly 10 percent chose to seek revenge 10 or more times. The second, and more striking, was that when the game was played without the option to penalize cheats, cooperation quickly broke down, people contributed much less, and the overall earnings were significantly diminished. But when the game was played with the possibility to punish, cooperation was greater, players contributed more, and earnings were higher.

What does all that have to do with people freaking out about Citi Bike? Mostly, it means it’s natural. When a group of people believes a rule is being broken, they want to punish the violator. In some primordial sense, punishment doesn’t need to fit the crime as much as it needs to happen in some form.

And that it does happen is actually a good thing. Cooperation and the social contract allow for something like Citi Bike to work. For streets to function, for society to sustain itself, people who feel they have been cheated need an opportunity to freak out, act crazy, and do their (harmless) damnedest to settle the score. That’s what keeps them in the game, and keeps them contributing, and keeps us all working towards some semblance of a communal life in a city filled with millions of self-interested jerks.

So keep it coming, I say: Keep grousing and yelling and finger-pointing over a few thousand blue bicycles and a couple hundred stations. I don’t agree, of course, but I’m certain we’re better for it.