Five hundred years ago, when you crossed the East River into Brooklyn, passing through the encampments of what would become Bushwick and Williamsburg, you’d eventually make your way to the ocean, where you’d begin to find clams the size of dinner plates, and where—late last summer—I spent what seemed like a perfect week with my family.

We lived in the Middle East, where we had a little girl, and where my wife was a reluctant war reporter and where it felt like we might not make it another year. Times were strange, because among other things, we’d just sold—after seven years of ownership—our tiny apartment on the Lower East Side.

The place we’d rented in August? We half-seriously thought about buying it. Untethered and reeling and searching for something, maybe we thought this was finally the way to come back, if ever we could. We’d tried and in some ways we’d failed and then we’d found something new and then maybe we were ready for something old and everything seemed to be falling into place, and then the rains came.

“We are used to thinking of American beginnings as involving thirteen English colonies,” writes Russell Shorto, in his masterly history of New York City. “But that isn’t true.”

The real history of America, he says—the beginning of a country that would change history—was instead forged on “a slender wilderness island at the edge of the known world.” In other words: “Manhattan is where America began.”

God, to live on that island—or even just to work there—for a while it was to feel every ounce of your body agreeing. When Kelly and I arrived, in 2004, we were newly married, cocky and malarial, coming off several years of living and working in Southeast Asia. Ready to take revenge, we moved to New York with everything we owned in the back of a Honda hatchback we’d bought for $500. I was from a nowhere suburb in south Florida and Kelly was from a small town in central Illinois. With the stink of people who’d landed at LAX, jumped in a car, and driven for several days, we bombed through the Holland tunnel, zipped down curving streets, until we met an old buddy of mine standing on the corner of Prince, probably half-stoned and dangling keys to an apartment in Brooklyn, where an old futon awaited us.

Because not everyone could live in Manhattan. Four hundred years ago, three-quarters of the buildings on the island were given over to the sale or making of alcohol. The land that now makes up the United Nations was a district where slaves lived. The natives the first New Yorkers encountered were still living a “late woodlands” life and could only gawk at things like knives and guns, the settler’s magic. But soon enough everyone had a knife.

It’s always been hard, boozy, and dangerous, and also, according to Shorto, from the beginning the colony was unmatched in the entire world for its assemblage of people from every continent, regardless of religion or background, everyone drinking and screwing and making money and eating like crazy, while up north they worried about witches and down south they obsessed about slaves. Shellfish carpeted the Hudson and East rivers, cool creeks ran down what is now the refuse-strewn desolation of the Lower East Side’s Cherry Lane, and as deer sipped at pools, the sound of leather boots maybe sending one scurrying, the screech of an owl: Life was great. Life was never easy. The best, the worst.

It’s a freezing day in January and I am on furlough from Beirut and my plan is to walk all the way back to Broad Channel—about 15 miles—but first I am standing on a familiar block on the Lower East Side, freezing rain dripping into my eyes, so far from the open ocean of that magical last summer, trying to be unmoved, but when I see our names, as yet unremoved from the grid of buzzers on an apartment building on Eldridge Street, just south of Houston, I am filled with regret. This had once seemed like the center of our universe. And now?

Walking over the Williamsburg Bridge, the same path Kelly and I had taken with the Honda in 2004, I am slipping on ice and slush and at the bridge’s apex, the spires of Manhattan come into focus through the fog and it takes my breath away.

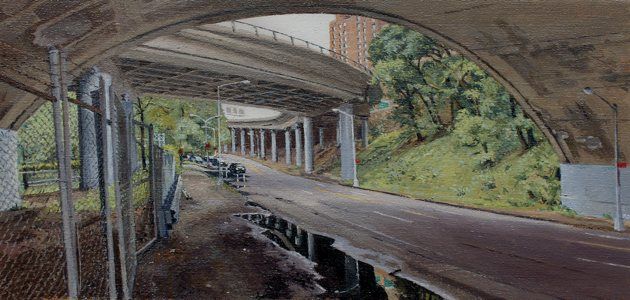

A few blocks away is the South Williamsburg flat we’d called home before ascending to an aerie on the island. Then as now, the neighborhood feels subhuman, an unwelcome convergence of bridge-exit traffic, a stop on the J train, and right above the BQE—such that a dinner plate, left on a counter for a night, would the next morning be coated in black grit—and I see that under the tracks, a cup of soup has spilled its guts. It’s revolting, like a tiny vulnerable human body has been smashed. Nearby, a UPS guy struggles under the weight of a package and staggers in what is now a driving, icy rain. I’ve walked about two miles so far. An ambulance rolls through a stop sign, crossing under the tracks, and I swear the old woman inside is moaning.

I keep walking, amazed, really, by how cold it can be, even with several pairs of pants on. I sidle up beside two black guys, one much taller, and they’re both walking fast and conspiring and discussing a woman who will buy benefit cards for cash.

Four hundred years ago, three-quarters of the buildings on the island were given over to the sale or making of alcohol.

“What ya got, six, eight kids?”

The guy stood to think. His buddy waited, their breath visible in the sleet.

“Eight,” he says.

They do the math out loud, skipping with delight.

“That’s what I’m talking about!”

It is crazy cold and I am beginning to get a blister, so I stop at a bar called Goodbye Blue Mondays, where my hands and thighs start to defrost. The barkeep lets me poke around and in the back I am thrilled to find this massive outdoor space but then I am saddened by the sight of a rocking horse, reminding me that I am far away both from my daughter Loretta and my wife. I get a beer. The barkeep agrees that, yes, things do change.

In 2006, while returning home drunk from a fancy magazine’s party, at which I’d lectured a well-known writer and instructed the editor in chief to hire my best friend, I dropped my wallet in our lobby and as a result of a series of bad and escalating decisions on my part, we were soon evicted.

On a whim, without really having any of the necessary money, Kelly and I put in a bid on a rat’s nest on the Lower East Side and then all of a sudden we had a mortgage and a contractor named JJ. The co-op board wouldn’t allow JJ to do any work in the evenings, when I was stuck in Midtown, and the place was so small, in any case, that I couldn’t really wrap my head around where you’d put all the bags of old sheetrock if you wanted to do some new sheetrocking. Then, when we wanted to take down a completely inessential little wall, the building demanded we involve the Department of Buildings, which required that we get an architect, and a permit, and pay all this money. I came to fear phone calls with 212 area codes. My wife took to answering our shared cellphone, this angry serpent that always wanted cash or credit.

Then, after five months, it was mostly done—our little Eldridge Street jewel, with hardwood floors, a ship’s porthole in the bathroom looking out onto the whole apartment, an old farm sink, butcher block counters, and exposed brick walls. Where once lived pigeons was now an old timber beam above a doorway, probably 100 years old, and from the bedroom—where behind some paneling we’d discovered a hatchet that appeared to be smeared in dried blood—there was a decent view of the Empire State Building, if you sat on the fire escape and drank champagne, which we did.

But at the same time, our contractor had bought a place, too, in the Rockaways, for the same price, and any pride in our great deal and smarts and good luck began to falter when we considered that JJ had done all our work and we were so deep in debt and, while our place was maybe 465 square feet, his was a two-story house, with several bedrooms, and a nice yard—three blocks from the beach. JJ surfed every day and his email address involved the phrase “good news.” That spring, we attended a shrimp boil in his backyard and by this time my work wasn’t going so great and the legacy of feeling so powerless about the apartment was beginning to spread to other areas of my life. I passed out in a bush.

Why had we ever bothered with that horrible island? Sitting there in Goodbye Blue Mondays, years later, my fingers working again, I pulled up the photo I’d taken before walking over the bridge. On unit 33, you’d still find our names—Nathan Deuel and Kelly McEvers. A little slice of Manhattan that had, for a while, been ours.

I talk to an old lady in a flower-print dress. She eyes me warily and says she has one room left. How much? It's $75 from 6 p.m. to 11 a.m. and it'll be $100 if I check in now.

We hadn’t actually lived there in years—we’d been subletting to various Europeans and ne’erdowells—and all along, no matter how far we’d gone, I tried to keep the possibility alive that New York was still big enough to include some corner that was right for us. Maybe not Manhattan, but somewhere? On a creaky internet connection, I’d carefully read about real-estate trends and sale prices, feeling this sad joy when The New Yorker reviewed a restaurant in our zip code.

Then, a few years ago, my dad was having trouble chewing steak that my mom had cooked for her 60th birthday. We were in Yemen when over a scratchy phone line we all discussed the likely diagnosis, and then we were in Doha when he had the surgery, and we were at last getting ready to fly via Dubai back to New York City when his health really started to fail. By the time I got there, he couldn’t talk or walk, and he was dead 13 days later. In the midst of this big grief, my wife took a job in Iraq and I moved with our daughter, Loretta, to Istanbul. Struggling to maintain connections, I pretended I was still in New York, obsessively following local news, reading about a new bar my dad and I would have loved. I kept a MetroCard in my wallet and set my weather to 10002. It felt like I didn’t know how to be good at living anywhere else.

Then suddenly friends back home were having kids and wanting more space and making more money and then everyone we knew left Manhattan, even our corporate lawyer buddy. If we ever came back, not just for a visit, but really came back, where would we go?

I’m walking again, all the beer gone, and my face is a wall of frozen tears or sweat or snot. The train rumbles overhead and I am entering my fifth mile walking across New York. Child care this morning at a facility in north Bed-Stuy is a Mexican-looking guy in a black button-down strumming a guitar to a room of 10 kids my little girl’s age. I watch through the window for a while but I begin to feel like a creep and also sad, and I am cold and tired and I consider how much a room would cost at the Neptune, a grim little hotel just a few blocks down, by the tracks. I buzz the buzzer and am let in by a thin black man with rheumy eyes and a grey afro. He gestures up a set of rickety stairs, where I talk to an old lady in a flower-print dress. She eyes me warily and says she has one room left. How much? It’s $75 from 6 p.m. to 11 a.m. and it’ll be $100 if I check in now. I smell like beer. I walk on. At a pharmacy down the block a woman in fur hat is looking longingly at the adult diapers.

This past August was our sixth or seventh trip back since we’d moved overseas again. It was the peak of the city’s annual stink, when an F-train platform could cause nausea but it was our only good time for a visit to New York, so last spring I wrote to a friend, relieved to discover his place in Greenpoint was available, inclined to just go ahead and book. But Kelly was adamant, saying we could do better. She really didn’t have time to look herself, but she wrote me reminders, even when on assignment. Let’s stay somewhere nice! That doesn’t smell like garbage! “Sorry Greenpoint, but you are floating above a lake of oil, next to a cesspool of sewage.”

I began looking at rentals in the Catskills, but I recognized none of the names, and then I discovered it would take hours by car to get to any of the rentals, and perhaps several days if you were going to walk. I even found one with all these exposed timber beams and a screened-in picnic enclosure near a babbling brook and a stove that looked like you could boil a bear on it. Then I looked the town up on the map. It was something like 150 miles outside the city.

I found the whole Fire Island and Hamptons thing dispiriting. I did not feel like a guy who looked at rentals anywhere, let alone on such august spits of real estate. One place with great photos of a lovely house was a “share,” in which you got a bed in a room with two bunk beds—along with something like 20 other people. The cost for the week included unlimited food and drink, which seemed amazing. “We got all kinds of chesses for your sandwich,” the post read. “We got pepper jack, Munster, cheddar, Swiss, American.” As proof, I suppose, there was a photo of a tray of cheeses, beside which was a crushed Coors Light and a bikini top.

I remembered dimly, maybe in 2009, reading a newspaper story about a bunch of publishing people who go in together on a little shack, maybe in the Rockaways? On maybe Beach 90th street? The writer said there were screens in the windows and creaky thin beds, but he also said it was a few blocks from the beach. I found nothing similar, not on Craigslist, nor Airbnb, nor even when I emailed and called a half dozen real-estate agents. One week I logged into a site called Airbnb, searching for “beach,” which turned up an ugly studio in Bensonhurst. Another time, on Craigslist, a search for “ocean” gave me a dark two-bedroom in Bay Ridge, “right near a Crab Shack!”

Why did the Rockaways resist me? In the Middle East, the day of our departure approached, and I was certain we’d never find anything. Why did we deserve something so special, anyway? New York was cruel. Maybe I’d dreamt up that story about the publishing people and the Rockaways? Fucking publishing people. Fucking New York.

“Is this New York? I never seen nothing like this.”

In May, there was a gunfight on our street in Beirut and Lebanon stank and it was hot and a motorcycle backfired and my heart leapt and my eye wouldn’t stop twitching and after all my wife’s hard work, after her challenging me to find us a cool place, I had to admit we’d probably end up back in Greenpoint. Which wasn’t that bad, not bad at all.

Then, a few weeks later, there it was. A listing for “Beach Cottage in Broad Channel.” The place, I couldn’t believe, was right on the water, near a stop on the A train, just a bridge inland from the Rockaways. The house had a deck and a dock, with two kayaks, and a view of the sunset over Jamaica Bay. It had an outdoor shower, and smart-looking chaise longues and tables made from old tin signs. It had a giant grill, outdoor speakers, and potted tomato, mint, and pepper plants. Inside was an airy space, with a big kitchen and breakfast bar, a nice desk, a giant but tasteful aquarium, a long couch, two snug bedrooms, and a bathroom right out of my wife’s dreams, i.e. clean and big and white.

In the first days of settlement by Europeans, this had been Indian land, crisscrossed with footpaths and stacks of spent oyster and clam shells. It would have taken the first Dutchmen more than a day to get here from the southern tip of Manhattan—through the brush and the forest, requiring a boat to cross the river, but worth it, if any of them had taken the time, or had any reason to leave the island, and they’d probably be as excited as I was, to get beyond the rivers and the bay and then to be so close to the crashing waves of an immense and improbable ocean.

And the price wasn’t that bad! With a beating heart I wrote the woman and told her I couldn’t believe it and surely it must be taken and then she wrote to say I could have it, and oh, by the way, it was for sale.

On the road, walking for the sixth hour, I am cold down to my bones, and I am also about as far from summer rental season as possible.

In unlovely East New York, the road starts heading downhill and I hear my first seagull and see my first ruined boat, and the tang of sea is in the air, my feet frozen and numb, and I get myself on a train to Howard Beach, where I can walk the final 10 miles—saving myself from a vast stretch of even more unlovely Bensonhurst. Warming up on the train, I nearly fall asleep, but the sound of someone opening a soda is like the crack of a rifle. A scowling white woman guards her purse. Everyone is tired. We pass stops called Liberty and Van Siclen and Shepherd.

I size up my fellow train riders, few of whom look all that thrilled to be in New York. I might be wrong, but I think that, if you’ve ever lived here, and then you leave—no matter what—you’ll find yourself forever and always talking at least occasionally about how great it was and when you’ll go back. It’s just a matter of how.

Broad Channel was over a bridge from the mainland, another actual island, and the car was packed to the gills with suitcases and coolers and sacks of oysters. Sun glinted off the waters of Jamaica Bay. Living there, I imagined, we could be city people and we could be beach people. We could enjoy the benefits of a cosmopolis, while enjoying the privacy and freedom of having our own backyard. We could ride our bikes to Brooklyn, but we could also paddle to a thing called Shelter Island.

My wife had recently crossed into Syria with the rebels. She’d lost colleagues to government shelling and worse, enduring stretches of 18-hour days, seven days a week, for months and months. The Middle East felt far away and it was such a relief to be surrounded by sun and sand and the wide swath of coastal forest that make up the wildlife refuge that borders Broad Channel.

In unlovely East New York, the road starts heading downhill and I hear my first seagull and see my first ruined boat, and the tang of sea is in the air.

Then we rolled past the first sagging houses, and I tried to ignore the trash and the brief commercial strip, which consisted of a bar, a gritty nail salon, another bar, and two delis, and then I was wondering if we’d made a mistake. Lining each block, I could now see, were single-family houses in various states of decay, between which were shallow and muddy canals. At the far end of the island was the bridge to the Rockaways, where a mix of homes, public housing towers, and sand would attract millions of New Yorkers each summer, only some of whom knew how to swim. We hooked a right on 12th Street. In a weed-choked lot was an abandoned car. A Rottweiler nosed through trash. A few homes seemed to be sliding back into the sea.

Then, there it was, our little yellow house. Our daughter ran up the front steps onto the porch, squealing, making quick work of the gate. I dashed to the front door, realizing we’d made no formal plans with the owner, Nicole, on how to get inside. The door wasn’t even locked. Inside were tall, drafty ceilings, walls full of windows, a fridge stocked with milk and butter, and on the deck—a real wooden deck—the very same chaise longues and tin-sign tables I’d seen online. A honk from our car broke my reverie, and I ran back to help with the bags.

I hoped Kelly would like it, and to my delight I found her oohing and ahhing at all the plants and the tasteful picnic table and chairs. I called Nicole to let her know we were happy, and I could hear her smiling thought the phone. She reminded me about the kayaks, and she encouraged me to paddle as much as we liked. I walked over to the big red beauties, amazed this was really happening. Just 45 minutes from Manhattan, we had boats! And a float dock, which at this point was sitting on the dark mud of a canal at low tide.

That’s when I noticed the neighbors, many of whom were staring at me. I peered around the decorative fencing—fairy lights! —and noticed a gaggle of leathery women, hands on sweating cocktails, arrayed around a glass-topped table, openly watching us. It was noon and I think they were already half-crocked. Dreamily, they took synchronous drags of thin cigarettes and said throaty hellos. Then I was addressed by the Captain, a stooped and living version of Popeye, with the same big biceps and watery-looking tattoos.

“You wanna swim?” he said, rubbing his belly. “No problem, I’ve been doing it all my life.”

He hacked into his hand and squinted with rheumy eyes, not exactly a living advertisement.

“Here, take this—for your kid.” I wasn’t even sure yet how exactly he knew we had a kid. Had Nicole told him? She had told me everyone was extremely friendly here—and nosy. But there I was, accepting a thoughtful if surprising offer of a vintage red tricycle.

“Thanks,” I said uneasily.

Kelly beamed. Then she crinkled up her nose.

“What’s that smell?”

I followed her out to the dock, where she leaned over and stared at the inky water, which was flowing right now into the bay. I was relieved to see the spent shells of ancient oysters and clams. But there was probably a lot more under there I couldn’t see.

Kelly volunteered to go buy stuff while I put Loretta down for a nap, and later that afternoon she returned with bags full of smoked fish, Russian sour cream, fresh greens, kielbasa, and corn, which was awesome, added to all the stuff we’d already brought: wine, dark rum, a bunch of ginger beer, five pounds of oysters, and five pounds of clams.

Before she left, she looked back through the sliding glass doors.

“It’s actually not that gross,” she said.

The next five days were a happy blur. Our friends came! How could they not? Even the guy who’d just had surgery to repair his detached retina came. I was high as a kite and asked him if it made him feel old, to have a detached retina. He said yes.

Loretta learned to ride a tricycle that week, whereas she’d formerly been terrified of her pink Huffy back in Beirut. Other things became possible, such as smoking weed more often than I had since I was in college, yet I felt completely at ease, except for a vague concern that someone might fall into the water. One morning, into the kayaks, we sent off an old friend’s girlfriend with our clumsiest pal, she paddling uneasily, he cackling deviously. Everyone was drinking, as I recall. When they didn’t return in time, her partner was pacing, saying they were late to a wedding. Then the pair paddled up, hooting and hollering. They’d seen fish jumping on the tide.

In a little kiddie pool filled with water, a staggering number of children from various couples grew sunburned together. It was hard to believe how quickly we ate all the clams and oysters, how many trips we took into the bay in the kayaks, that transportive feel of salt and sun on your skin, all of this a few blocks from a train that stopped in Manhattan. Toward the end, having had too much wine, I broke a precious glass, and in my frustration, I kicked the little pieces down through cracks in the deck, and they went tinkling into the sea. All along, I hadn’t even realized the water was literally right below us.

Could we live here? At the time, I thought we could. Kelly and I even came as far as discussing the details of a new mortgage. But I had to admit Nicole was probably asking too much money. And though Popeye had been sweet to lend us the tricycle, we hadn’t gotten the friendliest reception from the various teenagers who lurked around, or the rough-looking guy who revved his Trans Am each morning, or the Korean guy who had a 10-foot chain-link fence surrounding his fortress of a house down the block. The lots were packed in tight, no room to breathe, and it was daunting to think of keeping the peace among so many different kinds of people. Moreover, the city was planning to lift the streets several feet, a noisy and lengthy process, owing to rising seas and a sinking island. Every 12 hours, as the tide came in, some of the street would flood with murky water. My wife wasn’t sure a few feet would make the difference, and she was usually right.

Five months later, I am walking to the same house, and I am passing a FEMA disaster relief center, which is open from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. Two men outside look dazed. They hold cups of coffee—their jeans covered in mud and plaster dust and paint—and both look like they might fall over from exhaustion. A star-shaped painting nailed to a nearby electrical pole says, “Keep on going!” A house in the 500 block has an official sticker affixed to the front door that says “No Apparent Structural Damage.” The further I walk, the more I realize that, actually, nearly every house I see has a sticker from the Department of Buildings. Not everyone has no apparent damage.

Then I get to the yellow house. I knock and am greeted by a snow-booted Nicole, who invites me inside. She’s a wiry blond, maybe 5’7”, wearing sporty clothing and an amount of makeup that is more than the none you might expect, given the circumstances, and she begins to talk, fast, immediately. I’d last seen her from a moving car, as she drove up while we drove away. But that house! It had become like an extension of our bodies, a place Kelly and I had dreamed about and discussed at length. The sight of it in this condition—gutted, foul—takes my breath away. In the gloom and freezing air, I can see that, rather than the light-filled palace that had been the stage of so much delight, there is instead exposed wiring, an angry spray of black mold above a flood line high as your ribcage, yards of raw plywood, and the palpable hum of heartache. Ocean and rain raged in through the same sliding glass doors that may or may not still have had handprints from my daughter. I think I Windexed them before we left, but I’m not sure. It doesn’t matter anymore.

I feel like I’m about a foot taller than Nicole, and I am covered in sweat from walking all day, and mostly I am ready to curl up and go to sleep, but she is all muscle and nerves and intensity, and she immediately begins explaining how she has—almost entirely by herself—ripped down all the plaster, gotten new appliances, shored up the foundation, and reconfigured the house so it now has a much bigger kitchen and living room, but—and here I realize with some sadness—it now has only one bedroom. Where would Loretta sleep?

She discovered that her fish tank was empty, because the water had come up and over the tank and the fish presumably, hopefully, swam away.

“Ready to get walking?” she says, rocking on her heels, exhaling, smiling. Then she stoops to inspect the contents of a crate, which I realize contains her stout white pit bull. She pats the animal’s enormous flank.

The dog looks as excited as I am about the idea. I look around the room one more time, frantically inventorying what has happened to it—wondering what has happened to me—wanting perhaps to climb inside the one source of heat. Nicole has bought a wooden pellet stove, which is giving off an intoxicating glow. From walking all day, my feet are semi-functional, a blister festering on my left heel, and the last thing in the world I want to do is to get back on the road, but we had agreed to walk out to the Rockaways, to see the worst of the damage, so she rigs up her dog in a marvelously insulated coat and I have no choice but to follow.

Outside, back in the unforgiving cold, city inspectors are canvassing the street in orange vests and my daughter is far away and we will never live here, probably, and I am walking beside Nicole, with her dog, and I worry about its little paws because the streets are still covered in nails and insulation and shards of glass. I limp to keep up.

As we walk, Nicole recalls how she tried to ride out the storm in her house. The sound of the wind was terrible and things started flying off her deck and larger objects smashed into the walls of the house. The lights went dark, and in a horrible moment the night was lit up by the explosion of a power transformer. She ran with her dog through the rain to a friend’s house that had a second floor.

The winds howled and the rain beat against the windows, which began to shatter, and they watched as cars floated by, crashing against each other, toys, wondering if they were going to die, and then they didn’t die and in the strange morning light, her neighborhood a ghastly scene of mud and dead fish and broken boards. She returned to what was left of her house, and her knees buckled at the sight, but then she got to work, going for days without stopping or showering, remembering how, among other things, she discovered that her fish tank was empty, because the water had come up and over the tank and the fish presumably, hopefully, swam away. Missing, as well, was a 30-foot boat that had been tied to her dock. And the dock itself.

“Water is a beast,” she tells me. “So much can go wrong.”

We make it over the final bridge, and touch down on the Rockaways, which even five months later has the soggy, mildewed feel of an old shoe, just rescued from the bottom of a lake. The boardwalk is totally gone. Rockaway Taco, which I’d read about with envy, is now a soup kitchen. We look at one beachside mansion, where an entire half of the house was just ripped off and disappeared. A dining room table is still set, as if for dinner, and with the door ripped cleanly off, a hallway closet contains coats still hanging neatly on hangers. A broken water main bubbles and I feel like I can smell gas.

It’s time to go. I hug Nicole like an old friend and promise that I will stay in touch.

“I hope you move back,” she says.

Months earlier, a taxi was waiting and the September sun was shining and my daughter ran around, and we readied to leave a yellow house in Broad Channel, Queens. On Nicole’s street, I loaded bags into the trunk and then I noticed my feet were wet. It had been a full moon and the day’s tide was rising so high, higher than ever, in fact, so that oily-looking seawater was oozing onto the sidewalk and licking at the wheels. The taxi driver shot me a look of panic.

“Is this New York?” he said. “I never seen nothing like this.”

Just before I put the last bag into the car, I noticed these quick flicks of light. It was a pod of silver fish, swimming down the street, up and over a sidewalk in the city.