Alone, in my Brooklyn apartment, I was having a laugh at my late grandmother’s expense when suddenly, my drink—a full martini—slid the length of my desk and off the side, exploding on the hardwood floor, sending glass and Gilbey’s gin across the room and into the kitchen.

“Grandma?” I hollered.

No answer.

Would she travel more than 500 miles from her resting place in Little Washington just to break my martini glass?

Sure, she would.

I Googled the distance: 514 miles from West Ninth Street to Godley Road.

Grandma was a Godley. As a lifetime teetotaler, she would find little humor in the fact that I had once spilled Jack Daniels on her back porch after she had been dead nearly a year. I had gone down to Little Washington—L.W. to most natives of North Carolina’s Coastal Plain region—to say goodbye to my grandfather, who was dying of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It was a sad time, but boilermakers on the back porch lifted my spirits. Eighteen months after Grandpa died, Hurricane Fran leveled their home.

Last spring, I drove out to the vacant lot. All that remains is a circular mound that used to be a rose garden. The plush mat of fescue that had once covered the yard has been replaced with a riot of weeds and wildflowers, fallen oak and pine branches, and discarded soda bottles.

As I stepped out of my car, my mind dialed back several decades to a certain summer spent with my grandparents. A soccer ball rests on fresh-cut grass. Purple martins roost outside their 24-room home, their wary gazes fixed on two men and a 12-year old boy—Grandpa, my Great-Uncle Emmett, and me, sitting beneath a sprawling red maple.

“I keep seein’ it everywhere,” I recalled my Uncle Emmett saying. “Yesterday, it was on a mailbox, about a half mile down the street, near Willard’s pond and that poplar tree where Gaylord Alligood hung hisself.”

“Goodness gracious I reckon,” Grandpa says.

“Someone even sprayed it on the front door of the old Antioch Baptist church,” Emmett added.

“What you talkin’ about, Uncle Emmett?” I asked.

“The number of the beast,” he replied. “Six, six, six. Haven’t you read Revelation, boy?”

When it was hot outside, Grandpa and I usually spent the midday hours on the back porch, listening to country music and enjoying the breeze powered by a Hunter box fan. But today, Emmett was visiting. And neither Emmett nor a liquor bottle had ever seen the inside of my grandparents’ home. Grandma didn’t like Uncle Emmett.

He owned his trailer, his sisters did his laundry, and he ate from cans. At nearly 300 pounds, he could put away some food.

But I loved and admired him. He had served in the Army Air Corps during World War II, and had been stationed at Pearl Harbor when the Japanese attacked, an experience that had left him broken inside, unable to maintain steady work back home. Government compensation trickled in monthly. He didn’t need much. He owned his trailer, his sisters did his laundry, and he ate from cans. At nearly 300 pounds, he could put away some food.

Grandma cashiered at the local Red & White grocery. Every day at noon, when the fire department sounded its horn, she’d rush home to fix lunch for Grandpa. That afternoon, before Uncle Emmett’s visit, we sat down to a meal of buttermilk biscuits, country ham, and succulent, homegrown tomatoes.

The conversation wasn’t as lively without my siblings around. They were in Raleigh, visiting my mother’s side of the family. I focused on eating. Nothing matched Grandma’s cooking.

“Emmett might stop by,” Grandpa warned.

Grandma rose from her chair. “I’m heading back to work.”

“He’s slopping hogs for Willie, you know?” Grandpa noted.

“Emmett don’t move so fast,” Grandma said. “Willie’s entire herd is liable to starve if them hogs are dependent on Emmett for food.”

On the back porch, Grandpa settled into his rocker, lit a filterless Camel and turned on the radio. Porter Wagoner sang “Company’s Comin’.” I snatched the latest edition of Sports Afield magazine.

“Says here it’s a perfect day for fishin’!” I exclaimed.

“The day’s half over, Lucas,” he replied, calling me by my dad’s name.

“Tomorrow looks good, too.”

“Aye, aye, Cap’n,” he said, drawing hard on the cigarette.

He blew smoke across the porch. Some fumes escaped into the open air. Others curled up the walls and floated back toward us.

Grandpa brooded. I read about crankbaits. Johnny Horton sang “The Battle of New Orleans.”

The bluish haze of tobacco smoke descended on us like the morning fog over Goose Creek, and my mind took us out to that place where mullets leapt through the mist and splashed in the cool surface of the water during that post-dawn window before the sun burned through the vapor and forced every living thing to the bottom of the swamp. Live oaks and bald cypress trees, shrouded in Spanish moss, stood tall along the bank. A fallen oak poked through the placid weedy stillness of Hornet’s Nest Cove, our favorite spot for bream and largemouth bass. A plump water moccasin stretched out on the trunk. The serpent yawned, extending its fangs from the soft cotton-white roof of its open mouth—a warning to keep our distance.

“Lucas,” Grandpa announced. “I’m not gettin’ any younger.”

He lit up again.

“I won’t be fishin’ and building bird houses forever,” he said, spreading his tanned, powerful hands. A gold band with diamond accents encircled a thick ring finger.

“I want you to have this when I’m gone,” he added, tapping the ring.

I endured the speech with the usual discomfort. I pictured a world without him and knew I didn’t want to live there.

Uncle Emmett arrived. He extended a hand, and I grasped three fingers. He’d lost the others as a boy, blowing stumps to clear farmland.

He smiled, exposing naked gums.

I don’t know how he lost his teeth.

Under the shade tree, Grandpa handed me a plug of Cup tobacco. “Don’t tell your grandmamma I gave you this,” he said.

I savored the tobacco’s harsh, earthy taste. I welcomed its nicotine jolt.

“It’s gotta be them hippies in that corner double-wide,” Emmett says. “Who else would spray the antichrist’s sign on God’s house?”

“I hear President Reagan’s the antichrist,” I blurted out. “A boy at school says each of his names got six letters.”

Grandpa spat. “Now hold on, Lucas. Mr. Reagan is a fine Christian gentleman. You better hush up with that kinda talk.”

Emmett glanced down at his eight fingers, shrugged and counted them, spelling out the president’s full name.

“Boy, you’re right,” he said with a chuckle. “Ronald Wilson Reagan is six letters apiece.”

He resumed counting, his face fixed in concentration. He paused a moment, frowned, and then commenced another round of calculations. After a third try, he turned to me.

“If we stick with your six-letter theory, then the antichrist has already come and gone. You’re just too young to remember him.”

“Who was he?” I asked.

“Edward Roscoe Murrow,” Emmett declared. “A communist newsman.”

My parents had no love for Richard Nixon. But they revered Cronkite. At home, he was known as “Walter.”

Grandpa chuckled.

“Murrow started the whole liberal media,” Emmett continued. “Then Walter Cronkite took the reins. Cronkite hated President Nixon.”

My parents had no love for Richard Nixon. But they revered Cronkite. At home, he was known as “Walter.”

Grandpa leaned over and looked me in the eye. “Lucas, Mr. Nixon was one of our greatest presidents,” he said. “He just got caught. It was a witch hunt. A gang of liberals run him out of office.”

The next day, the phone rang at four a.m. Emmett had car trouble.

At the breakfast table, Grandpa poured black coffee into two saucers to cool it down quickly. We drank two mugs apiece this way, and after a bowl of instant grits, we loaded our tackle and the outboard motor into Grandpa’s Matador station wagon and headed for the outskirts of Aurora where Emmett lived.

We found him out front in a lawn chair with his red Honda cap pulled down over his eyes. Parked to his right was the AMC Rambler Rebel that Grandpa had sold him. With a black marker, Emmett had scrawled “For Sale” on a thick piece of cardboard and pinned the sign to the windshield with both wipers.

A coppery stream of tobacco juice shot out from beneath the brim of his cap, knocking a yellow jacket to the ground. The insect struggled. A phalanx of fire ants marched over.

“That car not good enough for you?” Grandpa asked him.

Emmett raised his cap and blinked a couple times. “She’s ailing, Isaac,” he said. “I gotta sell her ’fore she dies.”

Grandpa sighed. “That car’s got plenty of life left. Before I sold it to you, I replaced all her innards. She’s brand new under the hood.”

Emmett snorted. “She ain’t runnin’ right,” he said. “I was afraid to drive her over on account she might not make it.”

For most of his adult life, Grandpa had been a John Deere mechanic. He could fix anything—farm machinery, cars, trucks, motorcycles, even household appliances. Confident that the problem could be diagnosed with a quick test drive, he climbed into the driver’s seat and started the Rambler. The engine hummed. I slid into the passenger’s side.

“Sounds fine to me,” Grandpa said.

Then, he glanced at the mileage: 62,664.

“I’ll bet the odometer spooked him,” he said. “Emmett’s coming up on 62 years, and he’s just a couple miles from that number he’s been carrying on about.”

We eased onto Beaufort Path, a packed-sand road that merged with Highway 306. AM radio static crackled. I tuned in the country station. A local huckster hawked used cars. The pungent stench of Willy’s hog farm filled the Rambler. We passed Antioch Baptist.

“Maybe he’ll want the car back after we tack on a few miles.”

We approached the double-wide on the corner where sand met blacktop and pulled into the Cornerstone grocery across the street. Back in the 1950s, the place had been a roadhouse where my daddy drank beer and listened to rhythm and blues music.

Grandpa popped the hood with the engine running. While he examined the car, I wandered to the street corner to check out a rooster perched on a post outside the double-wide. The cock crowed.

At the end of the driveway was a “Beware of Dog” sign, mounted on a wooden tomato stake. Next to it stood a battered black mailbox someone had blasted with a shotgun. A rusty Ranger pickup sat out front. On a chain, tied to the door handle, was a mangy mutt nudging a bone.

“There’s nothing wrong with this car,” Grandpa declared, slamming the hood shut. “We’ll buy bait, drive a bit, and then head on back to Emmett’s.”

A figure appeared in the doorway—a grizzled man in overalls with a red bandana holding back his shoulder-length hair. He looked to be about thirty. He didn’t wave.

“I could use a Budweiser as long as your arm,” Grandpa said, as we entered the store.

Inside, men sat on joint-compound buckets. On our way to the freezer, a middle-aged fellow in a Texaco uniform stood and stretched his legs. Emblazoned over his left pocket was the name “Harkey.”

“You hear about that Aurora boy that blowed up his old man’s outhouse?” he asked his buddies.

Grandpa drove and drank beer from a paper sack. Charley Pride crooned “Kiss an Angel Good Morning.” Grandpa sweated through his shirt.

“How’d he do that?” inquired an old timer in overalls.

“Pipe bomb. Real shit storm.”

“Why’d he blow up his old man’s crapper?” asked a gaunt, buck-toothed twenty-something with long, greasy hair. His cap read: Leave Me Alone, I’m Havin’ a Fantasy.

Harkey shrugged. “I’m just tellin’ you what I heard.”

Grandpa drove and drank beer from a paper sack. Charley Pride crooned “Kiss an Angel Good Morning.” Grandpa sweated through his shirt.

I suppose we had been gone about a half hour. Emmett hadn’t budged. Grandpa handed him a tall Budweiser. “That hippie neighbor of yours offered me $500 for your Rambler,” he said with a smile.

“Who? Charlie Manson?” Emmett grunted. “Where’d you find him?”

“Cornerstone Grocery,” Grandpa said. “You still want to sell the car?”

“I’d just as soon sell her as not,” Emmett said. “Power company pulled the plug on me,” he grumbled.

Emmett stood, beer in hand, and stepped toward the car. But with the aluminum chair clamped to his ass, he didn’t get far. With three fingers, he tried to pry himself loose, but to no avail. His solution was to sit back down, set the beer on the ground, and free himself from the chair’s grip with both hands.

He trudged onward. Stuck his head through the open window and squinted at the dashboard.

“You’re going to need that car, Emmett!” Grandpa hollered. “If you want your power restored, you gotta pay your overdue bill in person.”

Emmett turned. His eyes settled on Grandpa.

“I reckon I will hold onto her awhile longer.”

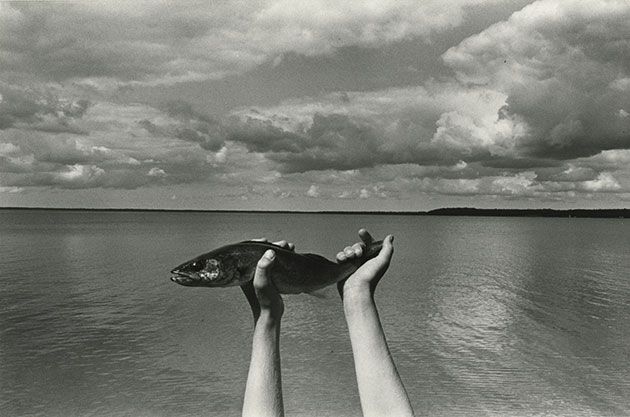

With disbelief I watched as Emmett repeatedly cast his silver Rapala floater. But after two hours of fishing with the same lure, he hadn’t caught a damned thing. By then, me and Grandpa had bagged a couple dozen croakers and spots. The shrimp had been a big hit that day. Even the blue crabs fought over it.

Grandpa hated crabs. Whenever I reeled one to the surface, he’d pound it with a boat oar until it let loose and sunk back into the river. I loved crabs. I could clean and cook them, too. But Grandpa forbade us to keep them. I never understood why.

Emmett’s stubbornness and slow, mechanical movements had begun to irk me until I got another bite and was nearly dragged overboard when the fish swam beneath the boat. After a five-minute fight, I pulled in an eel that must’ve measured three feet. I grabbed my line and hoisted it up. Ten-pound test dug into my hand as the eel wiggled, spun, and flipped about.

Grandpa removed a dirty, pint-sized plastic bottle from his tackle box. On it was a red label with a white skull and crossbones. I couldn’t make out the lettering.

The eel corkscrewed. Grandpa poured a generous slug into its mouth. The eel went limp.

“What you give him, Grandpa?” I asked.

“Poison, Lucas.”

I cut the tangled mess from the end of my line and tied on another rig. I rubbed a shrimp against the side of the boat for good luck and baited my hook with him.

Emmett’s hardheadedness persisted.

“Why don’t you switch lures?” I asked him. “You ain’t catchin’ nothin’ with that Rapala.”

He smiled. “You gotta have patience, boy.”

Too laid back for his own good, that’s what his problem was. And for a moment, I thought maybe there was a hint of truth to what Grandma thought of him. Maybe changing lures was just too much work.

“Antioch Baptist is takin’ up a collection for Horace Talmadge,” Emmett said, swigging from that same bottle of poison that killed the eel.

“What ails him?” Grandpa inquired.

“He lost part of his home. Horace has had a rough year,” Emmett explained. “And Devin, that no-count son of his, ain’t helpin’ none neither. What that boy needs is a haircut and an ass whippin’. He’s the whole reason the church got involved.”

Emmett passed the bottle to Grandpa.

“You know what that boy does for fun?” he continued. “He straps dynamite to live chickens and watches ‘em run around till they explode.”

“Goodness gracious I reckon,” Grandpa said, swallowing poison.

“But last week, one of them chickens run up under Horace’s porch and dynamited the whole back side of his house.”

The story sounded familiar, much like the tale I had heard in the store. “Wasn’t it an outhouse that blew up?” I asked.

Emmett cocked his head.

“I suppose you could consider that,” he said. “Horace’s home certainly smells like one.”

Emmett resumed casting, powered by patience and eel poison. I ate Lance crackers and drank Dr Pepper.

But the bird lacked a head. And a slick, rat-like tail dragged behind it.

Emmett’s rod tip jiggled. He jerked back and tried to crank the reel, but the fish pulled harder, stripping out nearly half of his line before Emmett thought to tighten his drag. His rod continued its dance, then dipped real low, and he leaned back, all 300 pounds of him, and lifted what appeared to be an enormous black bird from the water. Soon as it broke the surface, it glided over the river like a cormorant on reconnaissance, seeking a school of mossbunkers.

But the bird lacked a head. And a slick, rat-like tail dragged behind it.

“God-blasted stingray,” Emmett said.

“Manta ray,” Grandpa corrected.

Emmett’s line snapped. The ray soared another ten yards, then disappeared into the river with nary a splash.

Gnats entered my open mouth. I washed them down with Dr Pepper.

Emmett grinned. .

“Remember what I said about patience, boy?”

We gave Emmett a third of the fish. At dinner, I recounted the story of the manta ray. I noted how calm Emmett had been all afternoon, and how he had taught me the importance of patience. And I stressed how Emmett’s patience had finally paid off after an entire day of seeing no action.

Grandpa shot me a stern look.

Grandma scowled. “You mean all he caught was a sting ray?” she asked.

“Manta ray, Honey,” Grandpa said.

“And he took a third of the fish?”

“We always divvy up the day’s catch, Ada.”

Grandma frowned. “I suppose we can’t expect much from a man who does little more than eat, sleep, and breathe,” she said. “But now you’re telling me he’s too lazy to fish?”

“Ada, Honey . . .”

“And what’s he doing filling the boy’s head about patience? There’s a difference between patience and downright laziness.”

Grandpa touched her arm.

“Honey, he helped Lucas untangle his line a few times. He even tied on a couple of rigs for him.”

“I didn’t know he was that agile,” Grandma said. “That’s really something, seeing that he’s missin’ two fingers on his favored hand.”

“Emmett was real generous with the boy,” Grandpa said, glancing over at me.

“Sure was,” I chimed with a smile.

“Now, don’t get me wrong,” Grandpa continued. “Lucas is a fine fisherman. He must’ve reeled in a dozen croakers today. But Emmett’s contributions can’t be ignored.”

I nodded in agreement.

Grandma’s eyes narrowed.

“Isaac, the boy’s name is Patrick,” she said.

Stuck in my head is this image of Grandpa, my siblings, and me in our Sunday best, our arms draped across one another’s shoulders behind Grandma’s gravestone. Grandpa looks frail and forces a smile. Next to him, my sister stands erect, propping him up. Her expression exudes resilience and courage. In March 1994, I hadn’t seen my brother and sister in over a year. Back then, we were scattered up and down the East Coast in different states. Funerals bring family together.

That week, there were two funerals—Grandma’s and Uncle Emmett’s. In just six days, Grandpa lost the love of his life and his only remaining brother.

Before I returned to Brooklyn, Grandpa gave me his gold ring. I got it to fit with the help of an insert and wore it after he died until it disappeared during one of several moves. Sometimes, I dig through boxes and dresser drawers, searching for that ring as if finding it will bring part of him back.

At my bedside, there’s an octagonal table that Grandpa built. On it is a wooden cigar box where he used to keep grooming items. Whenever I open it, there’s a faint aroma of his hair tonic and Mennen Skin Bracer aftershave.

Sometimes, after I’ve knocked back a few martinis, we’ll have conversations. I’ll recall Emmett’s obsession with the antichrist, and Grandpa will remind me that his brother never picked up The Good Book and actually read it. Now that I’m a grownup, we can talk politics, and I’ll gently inform Grandpa that Sen. Jesse Helms wants to cut entitlements. He fires back that there’s too many liberals in Congress.

There’s not a day that passes when I don’t think of him.