Throughout the history of baseball, team owners have alternately amused or infuriated fans with their imperious ways. Bill Veeck, the peg-legged impresario of several clubs, sent a dwarf up to bat for the St. Louis Browns in 1951 and started a riot with “Disco Demolition Night” at a White Sox game in 1979.

Others, such as Connie Mack, Charlie Finley, and Harry Frazee, shattered hearts by selling off championship teams in Philadelphia, Oakland, and Boston, respectively. In more recent times, George Steinbrenner and current Miami Marlins owner Jeffrey Loria have put together baseball resumes that deserve an inquiry at The Hague.

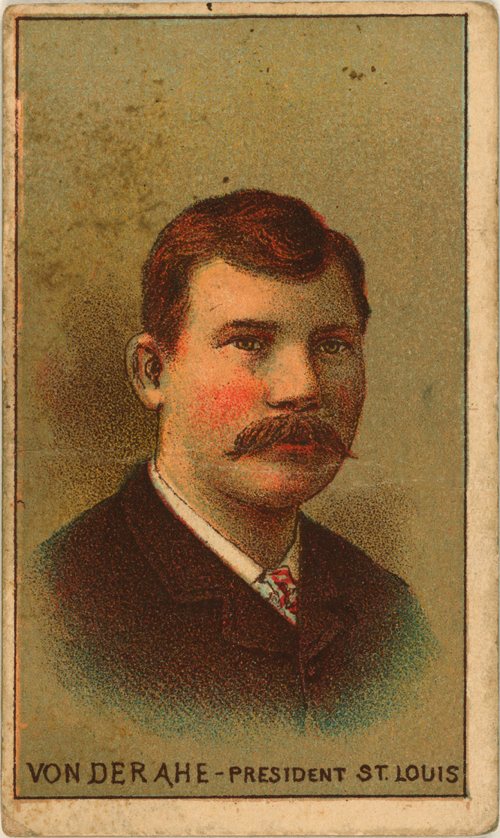

But before any of these owners made their reputations, the controversial Christopher von der Ahe1, “Der Boss President” of the St. Louis Browns in the 1880s and the first great populist owner, was leaving his mark on the game.

Baseball’s origins remain obscured through myth and time, and even after the Civil War the game was amateur or semi-pro at best, played by local teams without any league affiliations. Change came in the 1870s with the organization of league play, although major league baseball was an unrestrained mess in its initial incarnation, which only lasted from 1871 through 1875. There was no fixed schedule, and gambling interests openly took bets from the grandstand, while the inebriated players disgusted the rapidly disappearing fans (then called “cranks”) with their cursing and flagrant crookedness.

One baseball bigwig just as fed up as the fans was William Hulbert, Chicago coal magnate and president of the White Stockings from 1875 until his death in 1882. A stern individual with the visage of a bilious snapping turtle, Hulbert vowed to end “drunkenness or bummerism” and transform baseball into stolid entertainment for the upper-middle classes. Gamblers would be dealt with harshly, alcohol sales banned, ticket prices raised in order to keep out the mob, and blue laws forbidding Sunday baseball stridently enforced. Hulbert was also determined to take the game out of the unruly hands of the players, especially the “worthless, ungrateful, low-lived whelps” who threw games, and put it under the owners’ control.

Guided by Hulbert’s iron policies, the National League was formed in 1876. The new amalgamation combined the most successful clubs from the old league, including Hulbert’s White Stockings, with other franchises, and while the NL survived, it had its fair share of growing pains.

Hulbert’s unswerving commitment to bourgeois morals and strident oversight reduced rowdyism and prevented the league from disintegrating, but his dismissal of Cincinnati—for its insistence upon serving alcohol—and also of New York and Philadelphia—two big but misbehaving baseball hotbeds—in favor of teams from small New England and Erie Canal towns hamstrung revenues. Without their share of big-city gate receipts, numerous clubs were in financial jeopardy. On top of it all, the introduction of the reserve clause, which bound players to teams even if they no longer played for them, as well as other attempted stratagems by NL ownership meant that the players were aggrieved by their suppressed salaries. Meanwhile, many fans were alienated by the high ticket prices and lack of Sunday games.

The new, conservative version of baseball that developed in the late 1870s had simultaneously filled a void and created a vacuum that sporting men couldn’t help but see as an opportunity. Within a few years a rival league called the American Association would form, an outlaw assembly which newspapermen derisively referred to as the “Beer and Whisky League.” Starting in the early 1880s, the AA gave Hulbert’s deliberately elitist version of baseball all it could handle. That the AA’s leading owner was a buffoonish saloon owner made the battle for the hearts and minds of the nation’s cranks even more of a donnybrook.

Largely forgotten and inexplicably excluded from the Hall of Fame, Christopher Von der Ahe was the clown titan of the American Association. As an adolescent, he fled compulsory military service in his native Westphalia, in modern-day Germany, and came to St. Louis, eventually rising from a grocery clerk to become a saloonkeeper and real-estate mogul. An overweight drinker with a thick accent, a Teutonic mustache, and a fondness for checkered suits that were gaudy even for the period, the barman couldn’t help but notice the powerful thirst of baseball crowds stopping in his West End saloon on their way to the nearby ballpark to watch the Browns. The crowds stopped coming, though, after an 1878 gambling scandal drove the fans away and forced the club to fold, and for a period it appeared that St. Louis was finished as a baseball town, left without a major league club and blackened forever in the withering opinion of Hulbert.

It took convincing by others—including Al Spink, later founder of the Sporting News—to enlist Von der Ahe’s backing to start a new team. He didn’t understand the rules of baseball at all, but Der Boss President, as he later titled himself, understood profits, and beneath his bumbling exterior was a keen business mind. He was entranced by Spink’s vision of a new club in a renovated ballpark, a multipurpose entertainment showcase that would sell alcohol by the gallon, attract newspapermen and pretty women in equal proportion, and in doing so revitalize the entire west end of St. Louis, where most of Von der Ahe’s business interests lay.

Craving celebrity, the moon-faced saloonkeeper applied to join the National League but, in Spink’s words, “The owners of the other clubs had no use for us.” It wasn’t long before the St. Louis group began to ponder creating a different league altogether, and eventually they allied themselves with other would-be owners spurned by the NL, men with brewery backgrounds or from cities expelled by Hulbert. In 1882 they formed the American Association, a baseball league that would be everything the NL wasn’t.

Their plan was simple: The AA would charge only a quarter for a ticket, half the NL ticket price, making the games affordable for the working classes, while Sunday games would be a regular part of the schedule, as that was the only weekly day off most laborers received. Expecting large crowds, the AA teams would raid the NL of its best players by offering them a solid incentive to jump leagues: namely, more money. Finally, beer and whisky sales would be encouraged at AA games, with Von der Ahe taking the lead in that department. After refurbishing St. Louis’s rundown Sportsman’s Park, with grandiose hopes of adding “a cricket field…cinder paths for ‘sprinters,’ a hand ball court, bowling alleys, and everything of that sort,” Der Boss President had a beer garden built in the outfield, which was actually in play! He also established a tradition that his Browns would march to every home game from his saloon, returning there immediately afterward to toast victory or drown their sorrows.

Such gimmicks were only the beginning for Von der Ahe, but William Hulbert was already appalled. With his fiscal interests weighing as heavily as his moral ones, Hulbert advised the nascent league, “You cannot afford to bid for the patronage of the degraded; if you are to be successful, you must secure recognition by the respectable. A Sunday playing club, that is at the same time accessory to beer hawking, is beyond doubt, a curse to any community.”

Gamblers would be dealt with harshly, alcohol sales banned, ticket prices raised in order to keep out the mob, and blue laws forbidding Sunday baseball stridently enforced.

The fledgling Association gleefully thumbed its collective nose at Hulbert and the National League. When one NL president tried to buy an Association player, the Association owner respectfully declined before signing off, “In the meantime, you miserable reprobate, farewell.” In Philadelphia, which was still bitter about the expulsion of the city’s NL team and about to become a member of the AA, a newspaper was even harsher, stating of the physically ailing Hulbert, “We hope to have the pleasure of writing at no distant future the obituary of a man who has done more to kill off the game in this country than any man living.”

Hulbert would indeed pass away soon, dying of heart problems in April of 1882, just before the start of the AA’s inaugural season, but the rivalry between the NL and AA would continue for another decade, and always at the heart of the battle was Der Boss President. When other Association owners agreed to a truce with the NL before the start of the 1883 season, each side agreeing to honor the other’s contracts and to no longer attempt to pirate players, Von der Ahe argued unsuccessfully to continue the war—a truculent attitude that might have been right in the long run. As a whole, the AA teams were considerably more profitable than their NL counterparts in the league’s first year, and the NL bosses were running scared. At a meeting of NL owners after the 1882 season, Detroit’s president lectured his fellow bosses, “You cannot afford to sneer at the American Association and call it the abortion of the league… No, gentlemen, you cannot afford to sneer at the Association. They are taking our players because they can afford to pay higher salaries.”

But the AA owners, either not realizing the strength of their position or falsely confident the NL couldn’t adapt with time, or most likely wanting to consolidate their gains too early in the contest, opted instead for the temporary stability of a truce. By ignoring Von der Ahe’s sharp nose for success, the outlaw league forfeited its best chance to truly take over the game. The Association would remain strong for a number of seasons, but it always remained the junior league, a position of innate weakness that gradually declined over the next 10 years toward collapse.

Meanwhile, St. Louis was transformed from a baseball backwater into the mecca of the American Association. Lauded and sensationalized by the hometown Sporting News, the Browns and their city were on the rise, and Von der Ahe enjoyed his newfound stardom to its fullest. Spending as lavishly as he drank, Von der Ahe placed a bombastic statue of himself in front of Sportsman’s Park, a statue one newspaper mocked as “Von der Ahe Discovers Illinois.” But no display was too blatant for the egoist; once, when the Boss became disgusted with what he perceived as an umpire’s bias, he shocked the sporting world by hiring a special train at the then-exorbitant amount of $300 just to shuttle a new umpire to town for the next game.

In a typical Von der Ahe stunt, when his Browns faced the NL champion Chicago in 1885, he helped christen the matchup between league winners as a “World Championship Series,” instead of a more humble American title that others had used previously.

Von der Ahe was a whirlwind of Falstaffian energies, as likely to berate his team in a red-faced rage as to bestow pricey gifts upon them, sometimes both together, during and after a booze-fueled tantrum. Der Boss President’s audacity knew no bounds. He encircled his ballpark with a horse racing track, placed a water slide with a small lake at its base in his outfield that doubled as an ice-skating rink in the wintertime, staged a victory fireworks show with tin mortars that blew up and seriously wounded several spectators with flying shrapnel, and created baseball’s first “Ladies Day,” with free admission for the fairer sex. With Von der Ahe staging virtually any gimcrack entertainment that would muster a paying crowd, Sportsman’s Park soon became known as Coney Island West.

His amusements also included womanizing, despite a wife and child, though his wenching tended toward the blackly comic. In one 1885 incident, Von der Ahe crashed his carriage right outside his house, and his wife was less than pleased to discover an attractive young paramour, named Miss Kittey Dewey, also emerge from the wreck. Unabashed by the scolding, Miss Kittey had the temerity to show herself at the park a month later, whereupon Mrs. Von der Ahe promptly bashed her over the head with a soda bottle.

Von der Ahe was a whirlwind of Falstaffian energies, as likely to berate his team in a red-faced rage as to bestow pricey gifts upon them, sometimes both together.

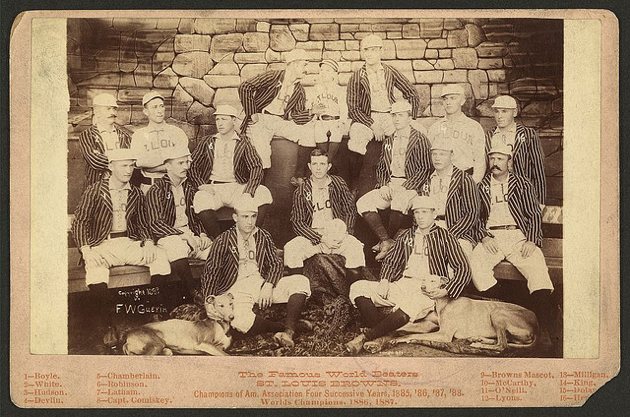

Der Boss President would continue to be unlucky with love, but on the playing field his Browns were the best club in the AA. Led by Charlie Comiskey, St. Louis won four consecutive pennants in the mid-1880s, and as a team they were no less colorful than their owner. Pitcher Jumbo McGinnis’s hefty gut was as much a result of overindulgence as of his offseason profession as a glass blower, while Comiskey’s tongue was among the most scathing in the game, a font of vitriolic obscenities backed by an extensive knowledge of the dark arts of baseball, such as storing balls on ice for use against good batters. Comiskey was a gentleman, however, compared to third baseman Arlie Latham, a ferocious bench jockey known as “The Freshest Man on Earth.” Latham talked so much that his own teammates couldn’t stand the sound of him, and after one season several Browns enlisted in a series of fights with Latham, each one wanting to beat the Freshest Man into silence. But the good times couldn’t last forever. The long battle with the National League took its toll on the American Association, which fell apart in 1891, while Von der Ahe’s wild lifestyle careened out of control. Debt-ridden, twice divorced, and estranged from his only son, Von der Ahe suffered one indignity after another. Sportsman’s Park suffered a terrible fire during a game in 1898, and Von der Ahe had a nervous breakdown, running shrieking through the streets as the park, his office, an attached saloon with an apartment above, and all his trophies were lost to the blaze, with insurance only covering a small amount of the actual damage. Eventually, the Browns were sold at auction, while a creditor, namely a shady ex-St. Louis player named Mark Baldwin, had Von der Ahe forcibly kidnapped by private detectives and taken to face a judge in Pennsylvania.

In 1895, he had a public breakdown of another sort, randomly assaulting a black stranger in the street and then shooting the man in the foot. He tried to deflect the blame for his bizarre attack by claiming that black neighbors were stealing liquor deliveries to his saloon, but his own staff denied the story, and in reality he was sending the booze to mistresses and filing false theft reports. Charges of assault with intent to kill were prepared, but the case was thrown out on a technicality after the victim neglected to provide security for court costs.

In the end, lampooned, bankrupt, alcoholic, and exiled from baseball, Von der Ahe barely emerged from his St. Louis house. Comiskey would later tell the story of visiting the ailing man in 1913, a reunion that left both men in tears. When Comiskey asked how he was faring, Von der Ahe replied, “I’ve got a lot and a nice monument already built for me in Bellefontaine cemetery.” Four months later, he was buried beneath the statue that once lorded over the entrance of Coney Island West.

Though his memory has been neglected, it was Christopher Von der Ahe more than any other owner who made baseball the game of the people, and if the game required the firm hand of William Hulbert, it also needed the immigrant business sense and beery showmanship of Der Boss President. Affordable tickets for the working class, doubleheaders on Sundays, attractions for women, gaudy promotions, carnival amusements for the whole family, urban renewal via a revitalized sports park, and last but not least cold lager beer—these things have continued to be staples of the game, adopted by NL owners and later American League magnates, all of them looking to enhance their crowds and revenues. Von der Ahe’s beloved Browns live to this day as well, although in a different form—one of a few AA franchises to merge with the National League in 1892, the St. Louis club changed its colors and its name, becoming the St. Louis Cardinals and the winningest team in National League history.

All of this from a fat German immigrant who knew so little about the game that he once boasted to reporters, “I have the largest diamond in the world!” Der Boss President may not have understood the mathematics of a playing field, but the form of baseball he pioneered has proven to be a gem.