We approached a house on stilts in Roaring Creek, a humble village on the outskirts of Belmopan, Belize’s blink-and-you’ll-miss-it capital, in search of a traditional bush doctor nicknamed Rico the Medicine Man. Gilbert, my hulking Belizean driver, said he could help me find Belizean bush doctors who make bitters, medicinal homebrews popular for treating anything from cancer to impotence to HIV.

But the dilapidated home we were parked in front of was protected by a chain-link fence, padlocked at the gate, and a pack of ferocious-sounding dogs barked maniacally when we pulled up. I was looking for a natural cure for MS, but I didn’t want to get out of the car.

Belize is known for its world-class scuba and snorkeling, its Mayan ruins, and its white sand beaches. But if you know where to look, it’s also a place to buy bottled, natural cures for every imaginable affliction. Nine years ago, I was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, and every day since then I have given myself an injection of a drug called Copaxone, which has a retail price of $60,000 per year. I do not know if the drug is effective, but I’ve felt pretty close to normal for most of the last seven years, so I’m reluctant to stop taking it for fear of what might happen next.

Thanks to our health insurance plan, obtained through my wife’s job, we pay nowhere near the medication’s retail price. But every time I get my 30-day supply in the mail and see the slip of paper with the $5,000 monthly sticker price, I get a sick feeling in my stomach. What if my wife lost her job, and the GOP repealed Obamacare, sending us back to the not-so-long-ago era when health insurance companies could deny coverage to anyone with pre-existing medical conditions? What company would write a policy for anything south of $5,000 a month to a guy who takes a drug that costs that much?

When I travel, I like to seek out natural medicine men and healers, mostly out of curiosity, but also because I harbor a secret hope that there are inexpensive, natural medicines that work just as well—or perhaps better than the criminally expensive stuff our doctors prescribe for us. I’m a natural skeptic, someone who isn’t prone to believing smoking peyote with a guy in a funny suit out in the desert is going to cure me of a serious illness. But I’m also open-minded enough that I’m willing to try different things, perhaps in the hope I can find a backup plan in case my prescription becomes unaffordable.

In the last year, I have consulted a Navajo medicine man in Utah and two witches, or brujos, in Nicaragua. None had cures for MS, but I came away from these encounters at least marginally convinced these medicine men and women had some kind of powers. Perhaps they were only capable of making people feel cured—but that counts for something. I was intrigued, so when I heard there were some legitimate bush doctors in Belize, I resolved to find one. On this day, I was looking for Rico the Medicine Man.

I’m open-minded enough that I’m willing to try different things, perhaps in the hope I can find a backup plan in case my prescription becomes unaffordable.

A woman emerged from the house, and the dogs stopped barking. She called out, “You looking for Rico?”

I couldn’t follow her exchange with Gilbert in Belizean Kriol, but she hopped in the back seat and we motored down the street, apparently in search of Rico.

“This is Rico’s sister, Yolanda,” Gilbert said, introducing us. “She says we were at the wrong house.”

We had been given the wrong address while asking around for medicine men at Belmopan’s central market. It was a drizzly afternoon in December and the road was marred with puddles the size of small swimming pools and potholes bigger than hot tubs. We passed a series of improvised homes on the road; the moody weather lent this impoverished community a sinister, melancholy aura.

We took a left down a rutted, rocky track and parked in front of a pastel-colored home across from a vacant lot where malnourished cows grazed amid assorted trash and tropical shrubbery. The next-door neighbor was doing laundry in a bucket outside and stopped to watch us. Yolanda knocked on the door as we stood back by the car, and a handsome young black man wearing low-slung shorts and no shirt came out to size us up. It was Rico’s son, Yolanda’s nephew.

“My dad’s out on a delivery,” he said. “But I have some stuff here if you need something.”

“He makes deliveries?” I asked.

“Within the area, he does, yeah.”

The young man showed me a big, white sack filled with various roots, herbs, and plants.

“What’s in there?” I asked.

“Balsam bark, galanga, chichimora, cochineal, gumbo limbo bark,” he said, peeking into the sack. “Do you have cancer?”

“Cancer? No, I hope not,” I said.

“Oh,” he said, sounding a bit disappointed. “Because he just brought back some Tallawanda, which is good for cancer.”

I was writing all of this down in my little notebook, asking them to spell the herbs, but no one had a clue. He had nothing for MS, but judged me as a guy who probably couldn’t maintain an erection, and offered me a homemade concoction called Rico’s Cold Out & Stamina at BZ$40 (US$20), which he claimed “cleans up your system” and is good for your sex life, but I told him I’d catch up with Rico another time for a personal consultation.

Before we parted company, Gilbert told me I should seek out a bush doctor based in San Ignacio, in Belize’s western Cayo District, with a delightful name: Harry Guy. Gilbert left me off in San Ignacio, an atmospheric little no-stoplight town on the banks of the murky Macal River, where I enlisted the help of two young employees of the San Ignacio Hotel who were curious enough to accompany me on my quest to find Harry Guy. They had never heard of him, but Gilbert had given me Harry’s telephone number, and a woman we saw walking in his neighborhood pointed us down Orange Street toward his home, a modest ranch-style house with laundry drying on a chain-link fence next to a sign advertising his business: Jungle Remedies.

Stephanie, a Salvadoran woman who worked at the front desk, was interested in finding a natural cure for pain in her knee. Trinity, a pregnant Bronx native of Belizean descent, who had recently moved back to Belize, wasn’t in the market for cures but seemed to relish our field trip as a reprieve from work, albeit under the vague pretext of assisting a guest. Harry invited us into his home office, where we took seats across from his desk, which was filled with plastic bottles of orange and reddish potions on the shelves.

I asked him if he was comfortable with the term “bush doctor,” and he said he was. He continued: “The type of diseases I’ve been curing is like cancer, high blood pressure…um…HIV, hepatitis B and C, and some autoimmune diseases,” he said. “I also give treatments for gallstones and kidney stones and heart disease. Let’s say you have clogged arteries, I could give you treatment to clean the arteries, so you don’t have to do surgery.”

I asked Harry if he’d ever helped someone with MS.

“Um, no. Most of the time when people come here it’s when, you know, their hand is all twisted up,” he said, twirling his hands to emphasize his point. “It makes it impossible to help them. Too late.”

I was disappointed but still curious about what he could offer and whether any of the bottles on the shelves actually worked. When I asked him rather bluntly if his potions were effective, Harry told me that he drinks his own heart medicine and cancer medicine as a preventive measure.

He claims to have cured at least 250 people with full-blown AIDS since he started his business in 1992, and hundreds or perhaps thousands of others suffering from a variety of other ailments.

“I’ve never seen a doctor in my whole life,” he boasted. “I know I’m going to die but I don’t want to die from cancer or heart disease.”

He said he learned his craft from his grandparents, who honed their craft in San Ignacio in the 1950s and ’60s, when there was no access road leading to the capital and there was only one doctor in the area, forcing many to rely on natural medicines.

“When people got sick in those days, everyone relied on plants to get healed,” he said.

I asked him if he counseled cancer patients to use his potion in conjunction with chemotherapy or on its own, and he didn’t hesitate. “You don’t need a doctor,” he said. “My cancer medicine is more effective than chemotherapy, that stuff is poison!”

Guy said he went out into the jungles every Sunday to secure his ingredients. He claims to have cured at least 250 people with full-blown AIDS since he started his business in 1992, and hundreds or perhaps thousands of others suffering from a variety of other ailments.

His treatments aren’t cheap—a bottle of the cancer medication is $50, a month’s supply of the HIV potion is $70, and the high blood pressure and cholesterol bitter is $80 per month—but it’s small change compared to the cost of prescription drugs in the US. He said the ingredients aren’t a secret: The HIV potion, for example, contains bark from a billy webb tree, mimosa herb leaves, and something he called uña de gato. The potions were all red or orange and looked like tomato or carrot juice.

Guy offered us shots of his “Quick Fix,” which he said was good to “rejuvenate the organs.”

“Not that I have this problem, but what do you have for impotency?” I asked.

“The Quick Fix works for that,” he said.

“It will give you an erection?” I asked.

“Yes, it will.”

“It’s like a natural Viagra?”

“No, no. It doesn’t work like Viagra because it’s natural. It doesn’t work instantly. But yes, it really works.”

I drank about an ounce or two of the stuff, which he claims has white anise, galanga, and balsam wood bark, among other things, and concluded it tasted like children’s cough syrup.

It is easy to lose faith in traditional medicine when you spend too much time in depressing hospitals, or trying to find a live person on the phone at your health insurance company who can explain why they aren’t covering this or that.

“So does this stuff really work?” I asked.

“Men come here and ask if I have something because their wife doesn’t want to have sex. I tell them yes, I have it, but I don’t know if it works.”

“Do you give it to your wife?” I asked.

“I don’t need it, no not yet,” he said, laughing. “Well, sometimes we drink it, but not all the time.”

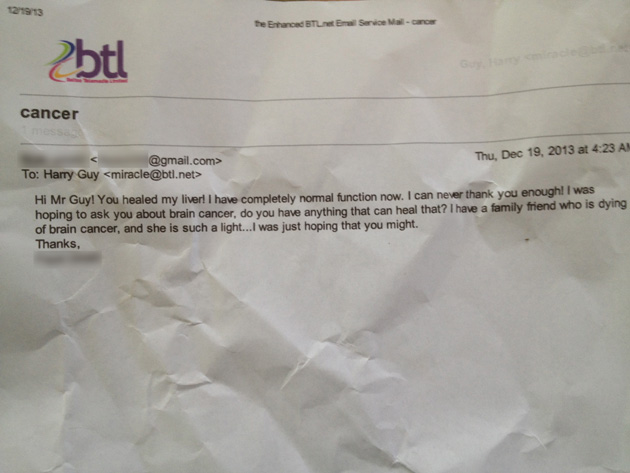

When I asked him how he could be certain his potions worked, he went to fetch testimonial emails from clients, including several from the US. One man, who Harry said was from California, wrote that he had nearly gone broke trying every cancer treatment imaginable. Nothing worked until he began drinking his Jungle Remedy potions, which he claimed gave him a burst of energy.

As I shuffled through the testimonials from Americans who had ventured all the way to this obscure town in Belize in search of cures or who had heard about Harry and ordered one of his potions through the mail (he will ship anywhere, he says), I concluded that they seemed authentic. These were people who had spent much more money and time treating their ailments in traditional medical facilities in the US and then sought out Mr. Guy only after all else had failed.

How had he, working from his humble home in Belize, cured people from a country with a seemingly superior health care system? In a way, it makes no sense. But I think all of us, the healthy and the sick, are looking for authenticity. It is easy to lose faith in traditional medicine when you spend too much time in depressing hospitals, or trying to find a live person on the phone at your health insurance company who can explain why they aren’t covering this or that.

Inside Jungle Remedies, there are no co-pays, no referrals, no injections, no invasive tests or forms to sign. There is just Harry, sitting at his desk, potions stacked neatly on shelves behind him. When he ventures out into the jungle each Sunday, looking for medicinal plants and herbs, he believes in what he’s doing.

I handed Harry the testimonials and asked him if he ever had any unsatisfied customers. He nodded in the affirmative.

“No medicine is ever 100 percent,” he said. “People want guarantees, and I don’t give guarantees.”

I have no idea if Harry’s Jungle Remedies work—except for the Quick Fix, which I can attest did perform as advertised—and, to be honest, I hope I’m never desperate enough that I need to rely on bush medicines from places like Belize to keep my MS at bay. But I do know that if visiting my neurologist in Chicago was as fascinating as talking to Harry, I’d look forward to my appointments. And if my medicine cost $50 a month rather than $5,000, I’d have plenty of money left over to spend on Harry’s Quick Fixes.