There’s a certain brand of movie that I most enjoy. Some people call them “Puzzle Movies.” Others call them “Brain Burners.” Each has, at some point or another, been referred to as “that flick I watched while I was baked out of my mind.”

But the phrase I find myself employing, when casting around for a succinct term for the entire genre, is “Mindfuck Movies.” It’s an expression I picked up from a college roommate of mine, an enormous Star Trek: The Next Generation fan who adored those episodes when the nature of reality itself was called into question, usually after the holodeck went berserk or Q showed up and hornswoggled everyone into thinking they were intergalactic dung beetles (or whatever…I never really followed the show myself).

Mindfuckers aren’t just Dadaism by another name—there has to be some rationale for the mayhem, even if it’s far-fetched (orbiting hallucination-inducing lasers!) or lame (it was all a dream!).

And they are not those movies where the audience (and the characters) think they know what’s happening, only to discover in the final moments some key twist that turns everything on its head. (Bruce Willis was balding the whole time?!) I love those films as well, but that’s not what we’re discussing. In Mindfuck Movies you know that Something Is Going On. It’s just not clear what.

Here are 15 16 of my absolute favorites from this rarefied class of motion pictures. And, really, the phrase “Mindfuck Movies” is too crude for such works of arts. These films are sophisticated. They make love to your mind.

Note: The text of this essay contains no spoilers, but watch the clips at your own peril.

Spellbound (1945)

Many of Hitchcock’s films dabble in the surreal, but how many include a dream sequence designed by Salvador Dalí himself? No, not three. No, not 11 either…dude, rhetorical question. And anyway, the correct answer is one: Spellbound, in which Hitchcock throws just about every brain-twisting plot element into the pot (amnesia, delusions, mental illness, etc.) and lets it simmer for an hour and a half.

The central narrative of Spellbound hews the conventional Hitchcockian template—innocent men on the lam from the law and the beautiful women who love them—but Spellbound heaps on psychoanalytical shenanigans until there’s an enormous question mark after the aforementioned “innocent.”

Note: This movie is in black and white. If the film you are watching is in color and features quirky kids striving to spell the word “smaragdine,” you put the wrong movie in your Netflix queue.

Rashômon (1950)

Face it: The vast majority of knowledge you have squirreled away in your head was put there by an untrustworthy third-party source, probably someone with an agenda to promulgate and an axe to grind. Akira Kurosawa drives this point home in his masterwork Rashômon, in which the events surrounding the rape of a woman and the murder of her husband are recounted by a number of witnesses, including a assailant, the woman, and even the slain man.

But this isn’t CSI: Kyoto, where every additional detail brings the big picture into sharper focus. Instead, the accounts are muddled, contradictory, and self-serving—and that’s before everyone starts changing their stories. Rashômon will force you to rethink everything you know about the movie several times before it’s over, and force you to rethink everything you know period well after it’s over.

La Jetée (1962)

This 28-minute film consists solely of still photographs, voiceover narration, and awesome. I’ve said too much already.

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Stanely Kubrick’s tour de force is grounded on scientific principles so sound that even now, 40 years after its release, it is still routinely cited as the finest “hard science-fiction” film ever made. (“Hard science-fiction” is defined as “stories in which Han Solo does not saunter around the surface of an asteroid wearing only an oxygen mask and a leather jacket”).

Yes, it’s a meticulously crafted and imminently rational three-course meal of a film. For the first two hours, anyhow. And then, in the final 30 minutes, it serves up a steaming bowl of WTF for dessert.

Why is the ending of 2001 so hard to comprehend? Because it doesn’t make a goddamned lick of sense—unless you read the book, that is. And this is by design. Kubrick and author Arthur C. Clarke intended the film and the novel to serve as companion pieces, to be consumed one right after the other.

Here’s another fun fact: The title sequence makes you feel like you can punch through walls!

Solyaris (1972)

Perhaps worried about the widening “Mindblowing Cinematic Science-Fiction Gap,” the Ruskies released this Solyaris four years after 2001 and doubled-down on the hallucinogenic quotient. Based on a novel by legendary sci-fi maven Stanislaw Lem, the plot revolves around a mysterious water-world and the cosmonaut in its orbit, as they attempt to communicate with one another. Think My Dinner With Andre if Andre were a Class-O Planetoid and the dinner consisted solely of psilocybin mushrooms.

Director Andrei Tarkovsky loved making these kinds of movies—his 1979 film Stalkers is equally fantastic, in both the adjectival and superlative sense. And he could also create a meditative, haunting, and beautiful sequence like nobody’s business, as the clip here demonstrates.

Videodrome (1983)

David Cronenberg’s meditation on the perils of media saturation may have seemed dated 10 years ago, but it has renewed relevance in a world so enthralled with the internet that people can utter the word “webinar” with a straight face. James Woods is a seedy lowlife (really playing against type there, I know) looking for the Next Big Thing for his porn cable station. When he stumbles across a pirate transmission of Videodrome, a “show” on which people are routinely tortured and killed, he resolves to discover the source of the broadcast and add the program to his lineup.

It’s fitting that Videodrome and the word “cyberpunk” were introduced in the same year, because the former is steeped in the aesthetic of the latter. It’s a film that skillfully raises not only questions (foremost among them: How did a film this fucked up get greenlighted?) but also your lunch, and watching it is a thoroughly unpleasant experience. Recommended!

The Quiet Earth (1985)

Remember when people worried that the Large Hadron Collider would asplode the planet? Yeah, so this movie is kind of like that. Physicist Zac Hobson wakes up one morning to discover that everyone else vanished from the face of the Earth when the mysterious “Project Flashlight”—on which he was working—was activated. (Coincidentally, the one episode of Project Runway I saw also made me wish all humanity would disappear from the planet, but I digress.)

Bruno Lawrence’s portrayal of a man alone in the world (and slowly going mad) rivals that of Charlton Heston in Omega Man. And there are more plenty more surprises in store for our dear, deranged doctor.

Jacob’s Ladder (1990)

Perhaps as a reaction to the gritty realism of ’80s-era Vietnam movies, director Adrian Lyne kicked off the following decade with this excursion into surrealism. Jacob Singer finds it increasingly difficult to keep his current life as a divorced postal worker disentangled from his memories of serving in the Vietnam War, and eventually everything starts blurring into a huge, incomprehensible mess.

Is he suffering from PTSD? Did he inhale some verboten chemical on the fields of war? Has he started traveling through time, Slaughterhouse-Five style? Or is he just plain nuts? His hairstyle provides compelling evidence toward this last possibility, but you be the judge.

The Game (1997)

Seeing Michael Douglas on a theater marquee is like seeing Chef Boyardee on a can: You know the contents will be cheesy and geared toward an eighth-grade palate. If that’s what you thought after Basic Instinct and Disclosure, you may have skipped The Game. And that’s a shame, because it’s actually an intelligent psychological thriller (or, as I like to call them, “Intellipsythrillogicalers”), and directed by the guy who made Se7en (which you loved) and Fight Club (which you loved).

It also provides an answer to the age-old question of what to get the man who has everything. And that answer, it turns out, is HOLY SHIT TERROR! After being enrolled in The Game, Douglas spends the rest of the movie trying to figure out if the people trying to kill him are just pretending to do so to give him a thrill, or if something has gone wrong and they actually want him dead. Sounds fun, but you can just get me Cranium, thanks.

Abre los ojos (1997)

César has it all: He’s rich, he’s gorgeous, he’s got a great friend, and has begun courting a beautiful woman. But when an automobile collision leaves him disfigured, his life quickly goes to hell in a hand-basket. Things get worse, and worse, and worse—until suddenly everything starts going his way again. It’s as if his dreams are coming true. All of them. Even the nightmares.

The overall premise is executed better in Vanilla Sky, the 2001 remake, but that film manages to come across as soulless despite being an almost shot-for-shot remake of the original. Abre doesn’t hide its secrets as well but feels more authentic, and though every character is flawed, you truly care about their fate.

Note: The following trailer is in Spanish. But you get to look at Penelope Cruz, so quit yer bellyaching.

Cube (1997)

When I missed an episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer back in 2000, a friend of mine loaned me a VHS tape on which he had recorded it. I watched it later that evening, and then spent another 90 minutes glued to my television, transfixed by the movie that followed. I was half convinced that the Buffy had overwritten the first 10 minutes of the film, the part that explained why these seven people were trapped in a giant metal labyrinth.

But, no: That’s just how Cube rolls. If you want answers, feel free to watch Saw instead, which borrows liberally from Cube’s traps-and-puzzles formula and then tacks on an ending to appease the masses. But if you’d rather just spend an hour and a half staring slack-jawed at your screen and wondering what in God’s Green Earth is going on, then Cube is the film for you. My buddy can even loan you the tape.

Dark City (1998)

I’m not going to lie to you—I love The Matrix. But I can’t help but feel Dark City was robbed. Released a year before Keanu and Carrie-Anne had us all wearing sunglasses and tight pleather pants (or maybe that was just me), Dark City treads remarkably similar ground and does so with more aplomb (albeit with a smaller budget). It also taps into that pre-millennium “my life doesn’t feel like real life” ennui that so many other films exploited around the same period.

Among its many other virtues, Dark City is also a masterful blend of a whole host of genres, from fantasy to science fiction to film noir. Indeed, figuring out the kind of film you’re watching—let alone what is happening within it—is half the fun.

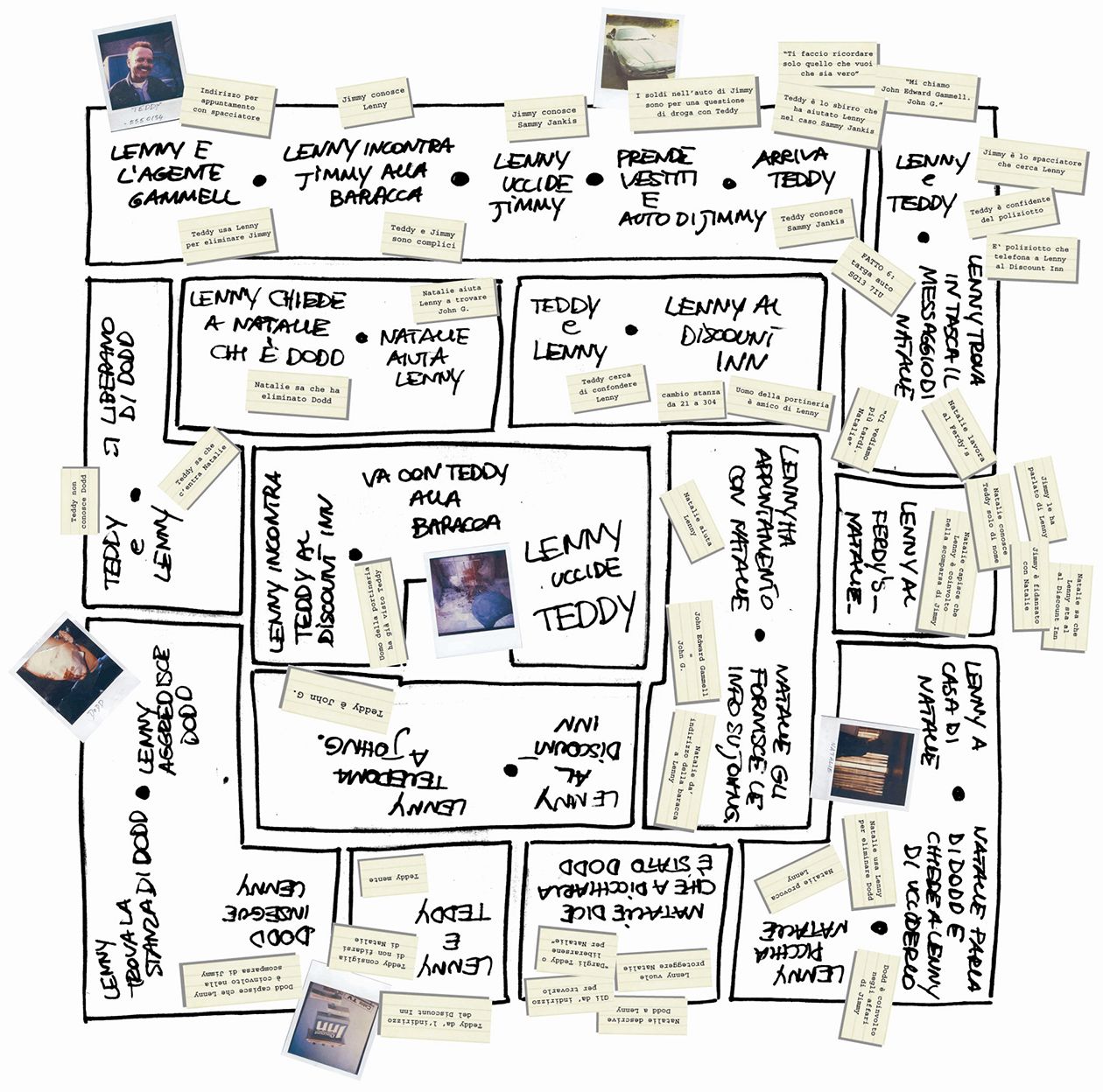

Memento (2000)

As I stood in line to buy my tickets, I noticed a small hand-lettered sign in the box-office window that read, “People arriving five or more minutes late to Memento will not be allowed entrance.” This was at a small art-house cinema—not one to place arbitrary restrictions on its patrons—and it struck me as odd that the limitation applied solely to this one film, so I asked the cashier about it when I reached the front of the line.

“You can’t understand anything about the film if you miss the first five minutes,” she told me with a roll of her eyes. “We’ve had late-comers charge out here after the end and demand that we explain the whole thing to them.”

Writer/director Christopher Nolan’s yarn noir tells the tale of a man with no short-term memory, searching for the man who killed his wife. It’s an intriguing premise made all the more engrossing by the unusual mode of presentation: The story is told backwards, with each scene only as long as the protagonist can hold in his head before he forgets all that came before it.

Confused? Don’t worry, it’ll all make sense when you see it. Unless you miss the first five minutes, apparently.

Mulholland Dr. (2001)

Here are the makings of a fun evening. Step one: Take your parents to see Mulholland Dr. Step 2: Endure the hottest girl-on-girl sex scene in the history of mainstream cinema while sitting a foot and a half from your mom. Step 3: Take your parents out for dinner afterwards, but instead of making chit-chat spend your entire meal staring into the middle-distance while attempting to make sense of the previous two hours.

It’s amazing that this film isn’t a mess. David Lynch originally filmed the story as a pilot of a television series, then re-shot some scenes and cobbled together a feature-length film after the studio executives took a pass. And yet somehow this rejected half-breed wound up as Lynch’s finest work to date. (“Better than Dune!” raves Matthew Baldwin of The Morning News.)

Donnie Darko (2001)

I originally omitted Donnie Darko from this list but then I realized I would get hate mail if I omitted Donnie Darko from this list so I put Donnie Darko on this list.

AND HERE’S A CLIP TOO ARE YOU HAPPY NOW JEEZE!

Primer (2004)

The first 20 minutes of Primer are among the most prosaic ever committed to celluloid: four wanna-be entrepreneurs dicking around in a garage, then sitting around a kitchen table stuffing envelopes. We know they are not working on anything new or exciting because the opening narration tells us as much. We know their previous research has proven fruitless because the characters argue about who’s to blame for their miserable lack of success.

And then they invent…something. The viewer doesn’t know exactly what they’ve invented, primarily because the protagonists themselves don’t know what they’ve invented. In fact, much of the film’s remaining 60 minutes focuses on their efforts to figure out what this thing does and how they can capitalize on it.

If the films in this list were arranged in order of ascending awesomeness rather than chronologically, Primer would still occupy the final slot. Made on a budget of $7,000 (seven! thousand!), Primer is one of the few movies I have ever watched twice in a row—and certainly the only movie I’ve ever watched at 8 a.m. after having watched it twice in a row on the evening prior. It’s like a deep-tissue massage for your brain—afterwards you may hurt like hell, but you’ll also feel strangely invigorated.