About a month ago, I had surgery. I am not sick, but the surgery was to reduce my risk of becoming sick in the future: a double mastectomy, a significant procedure for an otherwise healthy 31-year-old woman.

I’d been struggling with whether to do it for nearly two years, ever since I learned I carry the BRCA1 genetic mutation that predisposes me to early-onset reproductive cancers. My sister and I both inherited it from our mother. Typing the percentages of cancer risk for those with the mutation makes me cringe, as much for us women as for the simple, intractable nature of the human genome: The risk of breast cancer is as high as 90 percent, and 50 percent for ovarian. Breast cancer typically appears first. Thus, if you have not already developed cancer and been forced into decisions, as my sister has, doctors often recommend the prophylactic removal of one’s breasts and, eventually, ovaries, where the cancer is far more difficult to detect but whose removal is far more physically and existentially complicated.

I’ve always considered myself physically sturdy, the product of determined Irish, Swedish, and German farming stock. I’ve never sprained an ankle. The only bone I’ve ever broken is the forefinger of my left hand; it eventually healed, crooked but perfectly functional. I am not allergic to anything. Lately, though, I’ve thought about how much sturdier genes are than bodies: Bodies break and fall apart but the genes that comprise them remain steadfast, titanium double helixes. Bodies, it could even be said, break most often under the implacable weight of their genes, and will continue to do so forever, or at least until we truly master how to manipulate the genes, an eventuality that of course inspires ambivalence.

I know I am fortunate to have had the privilege and opportunity to make this decision that could help save my life. I am lucky that, when the pathology reports returned from the lab, the news was that my doctors had gotten to me before the cancer had. That said, this shit—testing positive for the gene, facing the decisions it forces, this surgery, recuperation, and whatever comes next—has been difficult. I choose those words—“difficult” and “shit”—carefully: Difficult is all this is. All the time, worse things happen, things that can’t, eventually and with effort, be scraped off the sole of the boot.

Two weeks gone from Brooklyn and I’m no longer sure what “literary type” means, nor I am sure whether I care, but I do know that I—the person I am—am supposed to love books.

Meanwhile, the months have been dwindling during which I can claim (translation: buy) comprehensive health insurance through my graduate program. I am technically still a student, yet actually just unemployed, so the possibility of getting cancer while uninsured has grown increasingly real and distinct. This is why I went ahead and did it now, while I can bask in the dual luxuries of coverage and time. That said, I’m not bouncing back the way I’d planned on or hoped for when I hoisted myself onto and under the lights of the operating table and stared up at the anesthesiologist’s surgical cap covered in smiley faces. Nearly four weeks out, and I still can’t shave my armpits properly. Pulling a shirt over my head requires a mental pep talk and I can barely lift a gallon of milk from the fridge.

As a result, all I’ve craved are suburban comforts. Chief among these: my dog, a television with decent cable, a car and a place to park it, and gas enough to get me with a short drive to someplace pretty in the country where my dog and I can both take a walk off-leash. These are some of the reasons why I am writing this not from Brooklyn, which has been home for the past four and a half years, but from my parents’ house in Virginia. Here, I migrate between my old bedroom, lined from floor to ceiling with books, and my parents’ library downstairs.

In my old room, the books on the walls contain a sense of accrued—or accruing—personal history. There are the classics from childhood that my mother refuses to relegate to the attic, holding out hope that they will be reread by her grandchildren who we may need to admit might never materialize: Blueberries for Sal, Outside Over There, A Child’s Christmas in Wales. There are also the young adult novels of my own adamant selection (the complete Black Stallion series), the books that recall fleeting high school fascinations (Bloomsbury Recalled, Exiled in Paris), those that smack of college (Literary Theory: An Anthology, The Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp, A Testament of Hope, The Wretched of the Earth), those that remind me how much I used to love poetry (Richard Wilbur, James Wright, Donald Justice, Stanley Kunitz), and then the translations of Polish poetry that remind me of my prolonged romance not just with poetry, but with post-war Polish poetry in particular (Czeslaw Milosz, Adam Zagajewski, Wislawa Szymborska, Zbigniew Herbert).

Charlottesville is an academic town, and my parents are academic types who have moved for decades in academic circles. The shelves of their library are a mini-history of this life. The shelf on the wall opposite where I am sitting right now contains books detailing the cities my father (an architect and urban planner) studied and taught about for years before he retired last May: Paris, London, New York, St. Augustine, Prague, Istanbul, Venice, Florence, Shanghai, Athens. The shelf to my right is filled with books written by my parents’ friends—The Colonial Revival House; The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party; Arguing About Slavery; The King of Babylon Shall Not Come Against You; Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945; The Female Imagination…

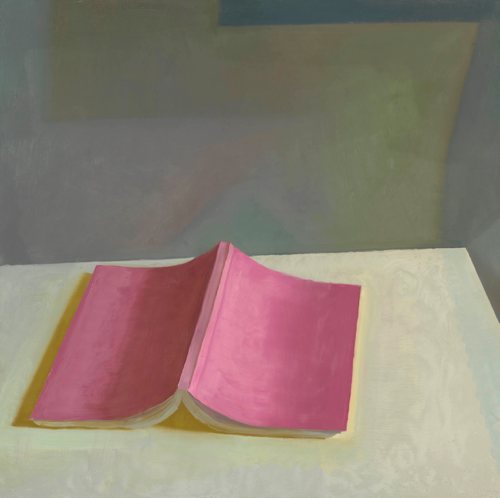

I list all these, but the books are not why I shuffle from one room to the other. I make the trek because the solace I find in the library, ironically, is in the flat-screen with cable that is mounted on the wall between the walls of books and opposite the couch where I sprawl among the pillows; the solace of my bedroom is, simply, my bed. Despite being surrounded on all sides—as if held hostage—by books, the last thing I’ve wanted to do for the past weeks (months, even, if I’m honest) is read. This is not a confession, just a fact: I can’t read. Or read, at least, with any pretense of endurance.

As much as I may want (or have wanted) it to be so, books haven’t been a sufficient comfort or diversion as I prepared to lose my boobs, then lost them, and began trying to adjust to their absence from my body. If I pick a book up, I’ll read a few pages before setting it aside because the end just seems too far away, the time and attention it requires, too exhausting. I don’t have the energy or patience for any of it. In the months before surgery, my attention span was shot through by relentless bullets of anxiety, the salve for which—it soon became clear—was not being left alone with my own head, a pile of paper, and a bunch of words written by some stranger; since the surgery, my attention span seems to have vanished under a haze of painkillers, muscle relaxers, and exhaustion.

Two weeks gone from Brooklyn and I’m no longer sure what “literary type” means, nor am I sure whether I care, but I do know that I—the person I am—am supposed to love books. Books have thus often been what the people who love me and who want to cheer me up in this time of need have been suggesting to me, giving to me, or handing me gift certificates to help me buy. Reread Pride and Prejudice, they say, offering over an elegant new edition. Or, here’s The BFG, or try this new novel by this new wunderkind, or these brilliant essays about war and devastation. But logic does not always hold. Just as the possibility of doing what you love for a job risks turning that love into a chore, doing what you love during a difficult time risks illuminating the shortcomings of that thing you love because it cannot solve all—if any—of your problems.

Those trying to help me be proactive about the BRCA situation are the ones who touch and trouble me most. They tell me to read Masha Gessen’s book about her journey with the gene, Blood Matters: From Inherited Illness to Designer Babies, How the World and I Found Ourselves in the Future of the Gene. I tell them I will, that I plan on it, but the truth is I tried to read the book but couldn’t. It was too much: too much information, too much of another person, too many pages. For each individual and each situation, what one needs to know is different and varies as the days, months, and years pass. There are those things one needs to know in order to make an informed decision and then there is the information that is too much to bear in the moment. This is why, too, when people tell me to read the FORCE (Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered) website, I nod, and say, “I’ve been meaning to do that,” then promptly steer as clear of the site as possible because I know I am not yet prepared for what I am sure is the treacherous black hole of BRCA discussion forums.

It’s not easy or appropriate to tell people who love you and who are trying to help you that what they are doing is not helping, that books are not what you want or need, that what you want and need right now are flowers, letters—notes, even—stupid movies, something that might help you feel pretty, emails that contain funny anecdotes from the outside world. That what you want is quiet company, conversation, to talk about you or him or her or whatever, who cares, that the last thing you want is to be left alone either with your thoughts or with a book chock full of someone else’s thoughts and into which your own encroach all too easily. Minds can become Frankensteins, and you’ve gotten gun-shy of yours and the noises it makes in the night. Of course, I don’t say any of this to those who hand me a book they say is lovely and that they hope I’ll enjoy. Instead, I say, “Thank you. I can’t wait to read it,” because that’s closer to what I hope I’ll mean in the end.

It’s not easy to tell people who love you and who are trying to help you that what they are doing is not helping.

Since I am not married and because my parents are loving and kind, my mother has borne the brunt of my physical and emotional caretaking these past few months as I struggled with decision-making and the eventual decision’s realities. She’s the one who has heard me most often respond to the question, “Do you want me to bring you a book?” with a matter-of-fact, “No, I’d rather watch TV.” Each time I’ve heard myself say this, I’ve watched her try not to judge me out of parental concern. Peruse the Facebook pages of any aspiring writers and you will see that most measure at least portions of their self-worth on what they have read or are reading; I am no different. I am, of course, jealous of those writers out there reading things I should be reading. The longest thing I’ve read in months is the New York Magazine profile of Gabrielle Giffords. Likely the only reason I made it all the way through that was selfish: an attempt to put my own situation in its proper place and perspective.

Instead of reading, I’ve stared at screens—television, computer, iPhone—until the whites of my eyes have gone red. And I’ve watched some very good television while doing so. I recommend The Killing and Party Down; The Good Wife isn’t bad because Josh Charles is dreamy and it’s pretty nice that TCM does not allow commercials to interrupt To Catch a Thief. I will say, too, that I seem to be able to watch and rewatch every episode of Parks and Recreation and not grow exasperated that they aren’t pumping out entire seasons on a daily basis. The business (or anti-business) of Occupy Wall Street unfolded on the news each night like a miniseries with a plot but no characters.

I also watch YouTube clips. These are usually concert videos because this means I’m multitasking: I can stare at a moving picture on a screen while also listening to a favorite song. Songs seem to divert and relax me these days, in ways that books cannot. For months too, I’ve gravitated in particular toward Emmylou Harris (with the Hot Band or Nash Ramblers), circa the late ’70s and early ’80s. I may not be able to read, but I can click through these clips past my bedtime. One of my favorite Emmylou songs is her version of “As Long as I Live” that she sings with Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Jessi Colter, and Roy Acuff, but I cannot recommend either of the YouTube videos with a straight face. Thus, my well-informed, yet predictable, recommendations are her performances from the years around when I was born of “Pancho and Lefty,” “One of These Days,” “Boulder to Birmingham,” “If You Needed Me,” “Hello, Stranger,” and “Leaving Louisiana in the Broad Daylight.” I am partial to the final lines of that last: It’s just an ordinary story about the way things go, ‘round and around, nobody knows, but the highway goes on forever, there ain’t no way to stop the water.

I read a profile of her once in which she talked about the black holes of outer space, not the soul. She told her interviewer the note that emanates from them is a deep and constant B-flat, a key she loves. She added, too, that a man who once played bass for her had synesthesia—meaning that when he played notes, he saw colors—and that when he played a B-flat what he saw was “very, very, very black.”

Clicking through YouTube clips occasionally has led me to scroll through the comment threads below. This is reading material I can manage, and these threads are usually about Emmylou’s physical beauty, a fact which brings me to those things that aren’t books and which also aren’t about how hot Emmylou was when she was my age, but which I can still manage to read.

These are the things—thoughts, words, sentences, paragraphs, pages—I have the stamina to roll my eyeballs over: there are the inevitable Facebook and Twitter feeds, which occasionally lead me to articles I can or cannot finish. There are the pieces of paper I get from the hospital that say in all caps in the upper right-hand corner, “Explanation of Benefits/This Is Not a Bill”; in the box that holds the dress I bought for job interviews and which I shipped to Virginia from a boutique on Lafayette Avenue in Brooklyn, there is a note from the shop girl saying she hopes I feel better soon and good luck; there are orderly lists of when and which medications I have taken; there are job listings that arrive in my inbox from Indeed and Idealist with infuriating regularity each morning and which I peruse before deleting because the jobs are all in New York and New York is no longer where I want to be; there are text messages and emails from friends and there are online shopping descriptions (“The gilded glass creations of Tamara Childs are sold in some of the world’s finest galleries…”). There are get-well cards that arrive via snail mail on old-fashioned paper and addressing me in old-fashioned handwriting from people who assure me I can do this and stroke my sense of vanity for being brave.

There is also the pamphlet my doctor gave me two weeks after surgery and just before I left New York. It’s called “Exercises After Breast Surgery.” It is 13 pages long, with large type, illustrations, and plenty of air between the lines of its paragraphs. It details seven exercises to be repeated five to seven times twice a day until normal flexibility returns to the arm and chest area. If I were to grade my progress, I’d give myself a C: There’s room for improvement.

My doctor tells me each exercise is important, but the last one most of all. It instructs me to stand facing the wall, my toes eight to ten inches away; it then tells me to put my hands on the wall and to use my fingers to climb it, reaching as high as I am able. Each ten to 14 times a day that I do this, as I stand facing that wall, making my fingers walk up, I am reminded of nothing if not the “Itsy Bitsy Spider” and its water spout.

The last of my reading materials these days is the occasional poem. Even these are only ones I’ve read before, which I already know I love, and which I’m probably not reading at all but simply repeating to myself from memory. The way the words to a song are easier to remember if you’re listening to it, a poem is likely easier to repeat if you are looking at it. I can read “Dedication” by Milosz, “Try to Praise the Mutilated World,” by Zagajewski, “The Layers” and “Touch Me” by Kunitz. The first line of “Touch Me” reads, “Summer is late, my heart.” Its last lines read, “Touch me/remind me who I am.”

I have one more imminent surgery. This one I’m not dreading. It will be for reconstruction and will mean the expanders that sit like 20-pound weights just under the skin of my chest will be removed and replaced with implants that, with any luck, will allow me to feel better about how I look in clothes and hopefully even in my skin. That I am able to string a few sentences together is because I’m off the Oxycodone and Hydrocodone, and down to just a couple Diazepam, some Extra-Strength Tylenol, and Advil daily. My mind again remembers the difference between “to” and “too.” The cloud of anxiety that descended before surgery has begun to lift, and relief has begun to register. The incisions have healed into tidy, tough, four-and-a-half-inch scars beneath what were once my breasts. I’m going to agree not to worry about the fate of my ovaries for a few years.

My first week or so down here, I didn’t feel well enough to do even abbreviations of the things I’d come to do: see my family, walk the dog, be outside, talk to an old friend and play with her baby, sit in the grass under the sun with my back against the fence and listen to my sister trot her horse in circles around the riding ring. Over the past few days and counting, though, I’ve felt a bit better, and in the afternoons I have been making a habit of taking the car and my dog out Garth Road where, after a few miles, I turn right onto a gravel road that runs the ridge between the Moormans and Meachums rivers.

I park and get out. I open the door for my dog, who jumps out and is off and running. I pause to admire and envy her athleticism even as she’s getting gray around the muzzle. Because the road is a ridge, the ups and downs of its topography are gentle, which is good for me because uphills present a challenge: It’s not easy to breathe deeply. But it’s getting easier, and I walk slowly. About halfway down the road is what I think must be one of the most beautiful views in the world, where a field backs up to the Blue Ridge Mountains. A green barn sits at the crest of the final rise before the mountains begin, and the way the light plays on the hills beyond the barn in the late afternoon when I’m walking gives me what other people say they find in church. We walk to the end of the fence line, turn around, and walk back.

By then, I am tired. I return to my parents’ house and curl up in my childhood bed, where I continue to eye the bookshelves from a distance. There are three volumes, however, within arm’s reach: A Year at the Races by Jane Smiley, the 33 1/3’s series’ Johnny Cash’s American Recordings by Tony Tost, and The Situation and the Story by Vivian Gornick. These are piled on the wooden desk that serves as my makeshift bedside table and which, 60-odd years ago, belonged to my mother when she was a schoolgirl in Wells, Maine. It’s as if these books are keeping vigil, as if they understand it’s not them, it’s me, and that the four of us are waiting together like family for the moment when I am able to reach over, pick one with purpose or at random, open it and commit to finishing what I have started without stopping to fret about how to make it through.