PAX Primer

Every year, tens of thousands of gamers descend on Seattle to attend a convention that began as a webcomic, and has grown into the epicenter of gaming culture. An account from this year's event, which encompassed nearly every imaginable game genre—and a few never before imagined.

A voice cries out from the middle of the crowd. “Rainbow Road!”

The conference room is filled, attendees shoulder to shoulder in slightly-too-narrow chairs. We are fixated on a large screen at the front of the room, onto which the Race Options menu for Double Dash‼ is being projected.

Someone seconds the motion—“Yeah, Rainbow Road!”—and within moments we’ve begun to chant. “Rain! Bow! Road!! Rain! Bow! Road!!

The referee glances at us briefly, mutters something lost in the din, and returns to his task at hand. He taps buttons on a controller, tethered to the Nintendo.

Behind him sit two teams of two players each, patiently waiting as the official selects engine size and lap count. They, and 16 more, are participants in the 2011 Omegathons.

Six have already been eliminated; this sudden-death race will end the dreams of two more. The 12 survivors will move on to the next stage of this six-round, three-day competition. Each Omeganaut has adopted a nom de guerre, Glitchy or Ainsmar or Saxicide or FluffyBunni.

Double Dash‼, released in 2003 for the Nintendo GameCube, is an installment in the enormously popular Mario Kart series. The original Mario Kart was released in 1992 and has spawned half a dozen sequels, but the core gameplay has changed little in two decades. Players steer go-karts around an assortment of tracks, flying off jumps, collecting powerups, and thwarting opponents with traps and missiles. For many people in this room, the regularity with which Nintendo releases a new Mario Kart title is a constant in their lives, as dependable as the James Bond franchise was for their parents.

The Rainbow Road racetrack, for which the room is currently clamoring, has appeared in every installment of the game. It is simultaneously revered and loathed for its legendary difficulty. Many players hate it, but everyone loves to inflict it on others.

But the ref does not select Rainbow Road, instead letting the CPU choose. The crowd is disappointed but understanding. Random selection of the racetrack is an Omegathon Rule. And gamers, of all people, respect rules.

To the crowd’s dismay, the course coughed out by the Nintendo is as far from Rainbow Road as possible, a drab mud track with a color scheme dominated by brown. Worse, Team One takes a commanding lead almost immediately. Their opponents, Nerdgasm and ArcticXC, look to be goners.

The energy seeps out of the room as the advantage held by the frontrunners becomes ever more insurmountable. Despite the buildup—the four matches that preceded this, the surprise twist of a tie that culminated in a runoff—this final race to determine who will advance to the next round is an anticlimactic snoozer.

With less than a single lap remaining, Team One encounters a string of disasters: They are struck by lightning; they crash into a wall of fire; and then, perhaps disoriented by this cavalcade of misfortune, they barrel off the road while trying to navigate the final bend. A small map in the corner of the screen shows the relative positions of the racers. Team Two is gaining ground rapidly.

Team One swerves back on course, and looks to have the match in the bag. But then: calamity! A turtle shell rockets out of nowhere and collides with their cart, knocking it into the air. Team Two enters from the side of the screen—their first appearance since the starting gun—takes the lead, and blazes over the finish line.

Throughout the room people leap to their feet, thrust their fists in the air, and cheer.

The circuitous route by which I wind up in a conference room on a Friday morning watching strangers play video games begins with a 1998 comic strip.

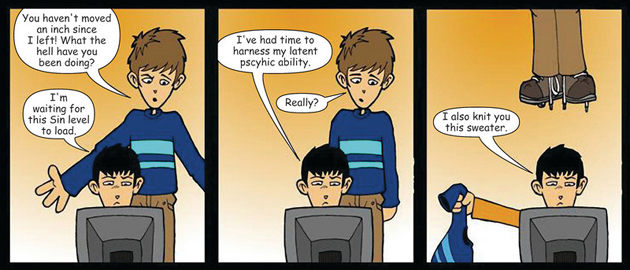

Entitled Penny Arcade and attributed to “Gabriel and Tycho Brahe,” this strip appeared in the thirteenth issue of Loony Games. The comic fit in well with the newsletter’s other content, articles about Quake level mods and the intricacies of procedural texturing.

Loony Games went fallow shortly thereafter, but Penny Arcade continued. By 1999 the creators, writer Jerry Holkins and illustrator Mike Krahulik, were publishing the strip thrice-weekly on penny-arcade.com, and supplementing the comics with blog posts. The posts provided context for the jokes, or elaborated on the positions expressed, or simply allowed Holkins and Krahulik to rant about whatever was stuck in their collective craws.

Even from the start, Penny Arcade was unusually popular. Part of its appeal was the quality of the material: The jokes were funny, the digital art was impressive by 20th-century standards, and the subject matter was perfectly pitched toward an audience of gaming enthusiasts. But Penny Arcade also offered readers something few other webcomics provided: a sense of connection with its creators. In addition to the blog posts in which Holkins and Krahulik speak to the audience directly, the two men also serve as the comic strip’s protagonists in the guise of “Tycho” and “Gabe,” respectively. And though Penny Arcade guys look nothing like their illustrated counterparts, their personalities, opinions, and gaming proclivities are channeled through the characters. So intertwined are the men with their alter egos that, in 1999, Gabe commandeered the strip to propose marriage to Krahulik’s girlfriend.

The Penny Arcade guys quit their day jobs at the turn of the millennium and threw in with an “affiliate marketing network” called eFront. That company evaporated into a miasma of scandal a year later. Unemployed and reluctant to rejoin the workforce, the two decided to double down on webcomics, and asked their readers to support them through donations. They eked out an existence until 2002, when the cavalry arrived in the form of Robert Khoo, a business consultant and fan who approached the pair with a plan for profit and an offer of two months’ free labor. The proposal was accepted, Khoo was hired a few months later, and Penny Arcade transitioned from comic to empire.

Since then the PA team has been involved in a string of adventures, side projects, and debacles. They were sued by a greeting card company for the misappropriation of Strawberry Shortcake. They got into a pissing match with then-lawyer and perpetually-nuts anti-video-game activist Jack Thompson. Several of their strips—a mediation on the nature of Wikipedia, the official rules of engagement for Nerf firearms—transcended their target audience and went viral, garnering links and new readers from across the web.

Along the way they also founded a charity, started a podcast that metastasized into a reality television show, did the writing and the art for a video game series, and wound up in Time magazine’s 2010 listing of “the world’s 100 most influential people.”

They also started an annual gaming convention. It is known as the Penny Arcade Expo, or “PAX” for short.

I had never before attended a PAX, despite living in its host city, Seattle, despite this being its eighth year, despite my status as a self-professed gamer. This, I have come to learn, is nigh unforgivable in my social circle, like a churchgoer who skips the most sacred holiday.

But I am a gamer of the tabletop variety, so PAX would be of little interest to me. So I thought. I began to suspect otherwise when nearly every member of my board game group snapped up three-day PAX passes when they went on sale in April, and expressed incredulity that I would not be joining them.

“I’m just not that interested in video games,” I explained.

“It’s not just video games,” I was told. “They have a library of board games, with, like, every title in existence. People play every night until two in the morning.”

It all sounded very Of Mice and Men (“Tell me about the Parchisi again, George”), but I decided to plunk down the 60 bucks and see for myself.

When the first Penny Arcade Expo debuted in 2004, and was held in a portion of the Meydenbauer Center. Thirty-five hundred people attended. The PAX of two years later not only filled the building but spilled over into nearby venues as well. By 2007, when it moved to its current home in the Washington State Convention and Trade Center, attendance had spiked to nearly 40,000.

Last year, like a stock that keeps appreciating, PAX split. The first PAX East hit the streets of Boston in 2010, and the Seattle original was rechristened PAX Prime.

On Friday, Aug. 26, the first day of the convention, I park my car on Capitol Hill and hike into downtown Seattle, passing the event horizon of PAX well before reaching my destination. Ten blocks away I see people heading toward the epicenter with bright red three-day passes bouncing on lanyards. Five blocks away I see my first novelty T-shirt: an arrow pointing left over the words “I’m With the Flanking Bonus.” The three blocks surrounding the convention center are nothin’ but nerds, save for isolated pockets of citizens uneasily eyeing the zombies and darting into The Cheesecake Factory for refuge.

The group is an impressive cross-section of society, with every age, sex, race, socioeconomic stratus, and BMI score represented. The days of gamer homogeny are long over.

So dense is the mob that the friend I am meeting has to text me detailed instructions on how to locate him, despite the fact that we are standing at the same intersection. He has flown in from Alaska to attend and has a one-day pass, the use of which requires a photo ID, but has left his driver’s license in the car. “I’m going to run back to my car and get it,” he says when we finally find one another. I tell him not to bother. “Just bluff your way in,” I advise, gesturing at the nearby entrance. “Most of these people have been bullied all their life. A little assertiveness will go a long way.”

I’m joking, but am quickly proven wrong on pretty much every count. For starters, the actual PAX checkpoint, beyond which badges are required, is not at the main convention center entrance but a gate four floors up. This is not to say that the three floors below it are PAX-less; quite the opposite. Every inch of the center is filled with games, game shops, game demos, signs adverting gaming room hours, and folks pressing flyers into your hand about other upcoming game conventions. It is as if I have died and gone to heaven, albeit a slightly frustrating heaven that doesn’t enforce the “stand right, walk left” rule on escalators.

Second, my description of the attendees as a bunch of flinching pushovers—a joke I am allowed to make as a member of the oppressed class—is well off the mark. The group is an impressive cross-section of society, with every age, sex, race, socioeconomic stratus, and BMI score represented. The days of gamer homogeny are long over.

Third, and pivotally, it turns out, the folks manning the checkpoints are unaffiliated with PAX. They are seasoned convention center staff, who shrug their shoulders indifferently when asked where to find the Halo Universe Fiction Writing Panel. Thus, after half an hour of crowd-wending, elevator-riding, and ineffectual attempts to text one other via the overloaded cellular network upon getting separated (“I AM AT THE 30 FT ROBOT STATUE”), we finally arrive at the main PAX entrance, only to have my plan of brazenly waltzing in promptly thwarted.

“Yeah, OK,” I tell my friend. “You should go get your ID.”

What does one do at a three-day gaming convention?

If one is me, one begins by getting utterly overwhelmed.

After finally gaining entrance to PAX proper I blunder into the video game exhibition hall, an enormous, dim, and labyrinthine area filled with kiosks for hot and upcoming titles. It evokes intense memories of Command Center, the video game arcade I frequented as a child with $20 in quarters weighing me down like ballast. Even at the peak of the 1980s video arcade craze, Command Center rarely had more than a dozen kids milling about at any one time. This pavilion, on the other hand, has throngs, flowing down the walkways like water in irrigation canals.

I drift with the current, occasionally stepping out of the stream to join a crowd. Here two PAX attendees beat the crap out of one another in the newest edition of Street Fighter, their brawl displayed on a gargantuan and elevated screen. Here a man slashes his arms through space while an animated ninja sword slices airborne fruit.

Over in a corner a designer shows off SpyParty, a two-player activity that could induce salivation in the Stanford Department of Psychology. In the game, one player controls the only human in a room full of AI-governed avatars, while his opponent peers in through a window, observing the crowd through the sight of a sniper rifle and trying to deduce his target from subtle behavioral cues.

By noon, thoroughly overstimulated and having reached the limits of my mild ochlophobia, I stage a strategic retreat: out of the video game exhibition hall, out of the convention center, east four blocks, and into the Six Arms, one of my favorite watering holes. There I put down a pint and peruse the PAX program.

The Penny Arcade Expo, it turns out, offers much more than just sensory overload. Seven theaters hold an array of lectures, discussions, panels, and workshops. Videogamers can see previews of upcoming titles, or play in competitive tournaments. Roleplayers can get advice on running a game, or designing one from scratch. Programmers can learn how to break into the biz, or ignore the biz entirely and release an indie game on a shoestring budget.

And running through the convention, the thread holding this tapestry together, is the Omegathon.

Registration for a PAX includes a checkbox asking if you wish to participate in the Omegathon. Of the tens of thousands of attendees who throw their name in the hat, a random 20 are chosen. Events are drawn from across the gaming spectrum: video games, console games, computer games, board games, card games. Previous Omegathons have included Pong, Jenga, Rock Band, Connect Four, and Skee-ball. Last year’s winner was determined via Toy Claw.

This is the first PAX for Anthony Yvarra. He’s long wanted to attend, but the time and expense of traveling from Portland, Ore., limited his participation to the Penny Arcade forums and living vicarious through PATV. This year, however, he scraped together the funds necessary for a three-day pass. Like everyone else, he checked the Omegathon box; unlike all but 19 others, he was contacted by Krahulik a month ago and told to suit up.

Here, he is known as Nerdgasm.

With the exception of the final round, which remains cloaked in secrecy, the games to be played during the Omegathon are public knowledge. Nerdgasm, alas, had played only one of them, at least at the moment when he first saw the list. Learning of his plight, the PDX PAX Facebook group rallied to his defense and organized a training party. Gamers take care of their own.

Round 2 brings him face to face with Bananagrams, described in the PAX program as “like Scrabble, only not boring and for old people.” Players receive 21 wooden tiles, each bearing a single letter, and simultaneously assemble them into a lattice of words. When a player has used all of his letters he yells, “peel,” whereupon everyone claims two more tiles from the central pool. When the pool is depleted, the first with no tiles left cries, “Bananas!” for the win.

At the signal to begin, a player typically examines his starting tiles and creates the longest word he can see. Today one player opens with “boozed.” Another opts for “lubed.”

Spelling counts. One player is knocked out of the Omegathon based on her use of “wavey.”

When the dust settles, it’s game over for four more Omeganauts. The good news for Nerdgasm is that he easily advances. The bad news is that Bananagrams was the sole game he had played prior to his training session. From here on out, it will be largely unfamiliar territory.

And yet he weathers Round 3 as well, held the following afternoon. Lumines Live!, the frenetic video game that is featured, seems both simpler and more vexing than its forefather Tetris. It is also, as the referee remarks afterward, a ladykiller. The eight advancing Omeganauts are all dudes, Nerdgasm among them.

Nearly all types of games are represented in the Omegathon, though roleplaying games are excluded. But that’s to be expected. After all, how many people want to sit around and watch other people play Dungeons & Dragons?

At the Penny Arcade Expo, the answer is: 3,040.

That’s the seating capacity for the Paramount, a concert hall two blocks from the convention center. On this beautiful Saturday afternoon, a steady stream of PAX attendees march out of the sunshine and into the dark confines of the theater, occupying every available seat.

In their defense (and mine), the “other people” playing Dungeons & Dragons are a laff riot: the Penny Arcade duo, Jerry Holkins and Mike Krahulik; Scott Kurtz, author and illustrator of PvP; and, of course, Wil Wheaton. The descriptions of many, many things at PAX conclude with “of course, Wil Wheaton.”

As with all good adventures, this one begins with a ballad. A spotlight illuminates a corner of the stage and two bards decked in Ren Fair garb use a flute, a guitar, and ye olde tymey doggerel to set the scene:

In ancient times, in a land far off

Full of goblins and mages

And kobolds and kings

Valiant men

Tempt evil’s wroth

For honor and riches and magical rings

This continues for a few more lines, until the tempo doubles and the romance evaporates.

Tonight four men

With some paper and some dice,

Will sit around pretending

That they know how to fight.

And move around some miniatures

And say some made-up words.

While every move is second-guessed

By several thousand nerds—

And I don’t catch the rest because the crowd erupts in laughter. We will remain in that state for the rest of the game.

Rather than conjure a fantasy world filled with monsters and suffused with wonder, this particular Dungeons & Dragons scenario is primarily designed to give the players ample opportunity to crack wise. As they prepare for play, for instance, Holkins says he built his character “specifically to get people out of pools of acid.”

Wheaton, whose Eladrin Avenger fell into a pit of acid during last year’s session, perks up. “Jerry,” he says, “I have an opening for a new best friend.”

“Hm,” Holkins considers. “Where is that opening?”

Later, during a scene in which Kurtz tries and repeatedly fails to climb aboard a skeletal dragon, every conceivable innuendo involving the word “mount” is made. When an errant fireball strikes the ceiling above the adventurers and reveals a secret trove of coins, the Dungeon Master describes the party as experiencing “a golden shower.” This goes on for hours.

The D&D game ends in melee, as most do, with players firing magic missiles and swinging halberds at undead minotaurs.

It’s all in fun, but Wheaton takes it very, very seriously. He picks up his sheaf of papers—character sheet, reference chart, rules summary—and studies them as the combat unfolds. When it is his turn to take an action, he agonizes over his decision for so long that audience members begin to shout suggestions.

As events like PAX consolidate gamers of all stripes into a single location, savvy game makers have learned how to target multiple breeds of gamers with single, hybrid offerings.

Among them is Sid Meier’s Civilization: The Board Game, a tabletop version of the classic computer game that condenses dozens of hours of play into three and combines all four Xs—expansion, exploration, exploitation, and extinction—with the ability to bellow “Suck it, Caesar!” directly into your opponent’s face as you conquer Rome.

“Everyone in this room is waiting for you to do something cool,” the Dungeon Master gently prods. But Wheaton will not be rushed. He pores over his paperwork, trying to find a maneuver or bonus that will give his warrior an edge. It is endearing beyond description.

Wil Wheaton is pretty much the patron saint of PAX. He is not a huge celebrity with a passing interest in games; oh, no. He is something much better: a minor celebrity, a relatable celebrity, for whom games are a passion. He gave the keynote speech in 2007, and has returned to the convention annually.

This year, in addition to his stint as Overanalytical Eladrin Avenger, he gives a one-hour presentation to a packed theater, the title of which, “Wil Wheaton!,” deftly summarizes the content. He tells stories about buying and playing games, stresses the importance of play to a fulfilling life, and fields questions from the crowd. When he apologizes for his state of exhaustion, blaming it on a roleplaying session that began last night and ran until 2:30 this morning, it doesn’t sound like a lame attempt to build rapport with the audience. It sounds like the truth.

Wheaton is both actor and inspiration to those of us at PAX. I was a teenager when Star Trek: The Next Generation debuted in 1987, and remember my excitement when his character was unveiled: Wesley Crusher, the 14-year old acting ensign who not only served alongside the crew of the Enterprise, but routinely saved the ship from disaster using his genius-level IQ.

Unfortunately, Crusher’s introduction to the audience was probably the zenith of his popularity. The character was soon dismissed as a mere Mary Sue, a wish-fulfillment proxy for the target audience member (i.e., me). When Wesley was written out of the show in 1990, most thought it good riddance.

But Wheaton soldiered on. He struggled to find work, dabbled in various careers, got married, raised children. He had moments of elation (he was offered a cameo in the film Star Trek: Nemesis) and moments of disappointment (his scene was eventually excised from the movie). And through it all he made time for gaming. To those who see him speak, or read his blog, Wheaton has become a real-life Mary Sue, an actual person in whom we see ourselves.

Wheaton is emblematic of a major theme in this year’s Expo: the integration of gaming into adult life. Panels entitled “The Truth About Being a Gamer Parent” and “How Gaming Can Keep & Save Your Relationship” provide tips on balancing social life and Half-Life. In the Raven Theater, Lev Grossman (novelist and senior writer for Time magazine) and Evan Narcisse (“professional nerd-for-hire”) lead a discussion on “Raising Kids as Gamers.”

“It actually wound up being pretty intense,” Grossman later says of the panel. “When I was little, games were something my parents were trying to get me away from, so I could learn about ‘real’ culture instead. Now games are part of the culture that I want to pass on to my own kids. We’re the first generation of gamers who are raising gamers, and there’s not a lot of good advice out there about how to do that. It’s something the community is going to have to figure out on our own.”

Another popular panel theme this year is how to break into the gaming business. “How the Hell Do I Get My Foot in the Door?” is the title of one. Another gives advice on tailoring a resume for a game studio. It seems as though PAX is populated with two distinct groups: youth who game all day and are looking for work, and adults who work all day and are looking to game.

As Nerdgasm strolls onto the stage, Jerry Holkins gives him direction. “Stand in front of our shame device!”

That would be an Xbox Kinect, a gaming console that tracks player motion instead of requiring a controller. Microsoft launched it last November, and had sold eight million of them by New Year’s. The Kinect is the fastest-selling consumer electronics device of all time, if Guinness is to be believed.

What could possibly account for the Kinect’s popularity? For one thing, it has a killer app: Dance Central. Featuring songs from the Commodores and Lady Gaga and everyone in between, the game displays an on-screen dancer and challenges players to mimic its motions. A correct move will garner a Flawless! rating and a set number of points, while an ill-timed pelvic thrust will earn laughter from those spectating.

ArcticXC keeps breaking into a smile, exaggerating his dance moves and adding flourishes to many; Nerdgasm looks as intent as a surgeon, keeping his motions as precise as he’s able.

And there are lots of spectators tonight: thousands in the theater itself, still more in a conference room blocks away, to which this portion of the Omegathon is being telecast. We have already watched two Omeganauts suffer the ignominy of performing the Humpty Dance. The second set wagged their fingers in time with Donna Summer’s “Hot Stuff.” At the end of each, one person was declared the winner and the other was sent packing.

Nerdgasm has been paired with his Mario Kart copilot, ArcticXC. They bound to their places before the shame device and raise their right hands, indicating to the Kinect sensor where they stand on stage. They don’t know what song is coming, but, based on previous selections, are doubtlessly braced for the worse.

Truthfully, it’s not that bad: Bobby Brown’s “My Prerogative.” It takes Nerdgasm and ArcticXC a few moments to get into the rhythm, and they flail like marionettes under an inebriated manipulator, but by the chorus they’ve hit their stride. ArcticXC keeps breaking into a smile, exaggerating his dance moves and adding flourishes to many; Nerdgasm looks as intent as a surgeon, keeping his motions as precise as he’s able.

His caution is rewarded. Nerdgasm is ahead on points by the time they reach the freestyle portion of the song, during which players are able to improvise. Finally able to let loose, he first performs a few seconds of the Robot, and then—oh, my God. Is he doing the Macarena?

As Mr. Brown concludes his discourse on free will, Nerdgasm is declared the winner. Congratulated and ushered offstage, the final two Omeganauts enter from the wings.

“Crank it up to maximum shame!” Holkins instructs the Kinect operators.

And they do. It’s “Baby’s Got Back.”

The Omegathon round ends, the shame device is wheeled into the wings, and it is time for the Saturday evening concerts. Paul and Storm take the stage and oh, hey, I recognize these guys. They were the bards from the D&D game. I did not realize that they constituted an actual band.

I appear to be alone in my ignorance, however. The rest of the audience knows the group well, and sing along when the set culminates in a lullaby to someone’s vagina.

There follows Jonathan Coulton, a singer/songwriter popular with this crowd for his funny and erudite discography. His track Mandelbrot Set is about the mathematics of fractals. I’m Your Moon is a ballad sung to Pluto by Charon upon its ouster from the ranks of planets.

Coulton’s biggest hit is an infectious little ditty called “Still Alive,” and everyone here has heard it—even me, which is unusual given its source. It was never in the Billboard Top 40 (or Top 100, or Top 1,000). It wasn’t in a movie. It has yet to be featured in a Mitsubishi commercial, as far as I know.

No, “Still Alive” was the closing song to a video game.

The lovely lass who enticed me into trying the demo of Fortune Street described it as “Mario Party meets Dragon Quest,” neglecting to mention that at least 85 percent of the game’s DNA was filched from Monopoly.

Dragon Age RPG, the paper-and-pen roleplaying game that kept Wil Wheaton up all night, is based on a video game, which also spawned a Facebook app, a web video series, and a few novels. It is like the Genghis Khan of computer games, just dropping progeny everywhere.

Now, if you haven’t kept abreast of game development for the last 20 years, you might conclude that this quote-unquote “song” must be a looping monophonic sequence of bleeps and bloops, perhaps with vocals by a speech synthesizer. In reality, “Stay Alive” is—well actually the speech synthesizer part is dead-on, at least as performed in the game. But Coulton’s rendition this evening sounds suspiciously like the sort of catchy folk/rock song you’d hear on your local indie radio station. If fact, it almost sounds mainstream.

Music is omnipresent at PAX, with shows nightly and a designated “jamspace” in which anyone can rap the Mario Bros. theme. Nearly as ubiquitous as the music is the question of when video game music will be embraced by society as full-fledged genre.

The consensus is: any day now. Witness the bestselling single of 2010, Ke$ha’s “TiK ToK,” which sports a decidedly 8-bit backbeat. Or the recent track “Never Been,” on which Wiz Khalifa raps over the theme from the 1995 Super Nintendo game “Chrono Trigger.” Earlier this year “Baba Yetu,” the title song for Civilization IV, was the first piece of video game music to win a Grammy.

That the line between video game music and regular music is blurring is unsurprising, given the confluence of gaming and mainstream culture in general. Even as the offspring of Wil Wheaton and Lev Grossman (those are two separate sets of offspring, FYI) are raised with gaming as a central part of their lives, gamers have seen their parents adopt “casual” consoles like the Wii and the Kinect. And the gamification of everyday life is the hottest of trends at the moment. Soon you won’t do a goddamned thing unless achievements are awarded thereafter.

Round five of the Omegathon is Portal 2, and will be difficult to understand unless you know how Portal works. Which is awesome, because I love telling people how Portal works.

Portal is a first-person shooter. Sort of. As in most FPS games, you see things through the eyes of the protagonist, a worldview that invariably has the barrel of a gun in the foreground. However, unlike nearly every other game of this genre, the gun in Portal is not lethal—not directly, anyway—because it does not fire projectiles. It fires portals. And you don’t shoot enemies, you shoot walls and floors and ceilings. You shoot walls and floors and ceilings with your portal gun, which makes portals, and then you travel through them, the portals. Are you with me so far?

The upshot of all this that you can place a portal onto the wall next to you, and another on a wall in the distance, and walk through the first to instantly emerge from the second. This is handy when there is, say, a trough of fire bisecting the room.

It also totally messes with your head. The solutions to many of the levels in Portal do not require you to mow down waves of faceless enemies, but rather to put down the controller for a moment and think very hard about how the world would work if you could join any two points in space and then pass from one to the other with no loss of momentum.

Among the many other features of Portal that set it apart from the rest: It is brief, dialogue-intensive, hilarious, and features a fantastic ending credits song (the aforementioned “Still Alive” by Jonathan Coulton).

Today the remaining Omeganauts are playing its sequel. Portal 2 introduced cooperative challenges, in which players work together to navigate a sadistic series of obstacles and rooms. The Omegathon organizers have perverted the spirit of this mode by turning it into a competitive event. The four remaining contestants have been parceled into two teams of two, and each is racing through the same nine levels. The first team to complete a level gets a point; the first to earn four points is the victor.

This round is a great idea on paper, but is confusing as hell as a spectator sport. One of the hallmarks of Portal is that you have to visualize what is going to happen when you do something before you attempt it; watching other people play, and trying to piece together what they just did based on the consequences, is like trying to deduce the history of Egypt from a photograph of a pyramid.

After a while I stop trying to follow the action and simply applaud when a point is awarded. I cheer loudest when Nerdgasm and FluffyBunni win their fourth point—and entry into the Omegathon finals.

It would be inaccurate to call Portal an “indie” game, given that the company behind it is also responsible for the hugely popular Half-Life. But the indie ethos is certainly there: The humor, the brainbursting premise, and the idea that a short game with innovative gameplay ought to be worth as much as, if not more than, an ostensibly long game that involves hours of repetition.

One of my favorites of PAX, Fantasy Strike is a card game recreates the feeling of the Street Fighter arcade game with uncanny accuracy. A buddy and I played it until we got kicked out of the convention center, whereupon I drove home, opened a beer, and played another half hour online.

About the only cross-genre “X: The Y” I fail to see over the weekend is a roleplaying game based on a board game. If you have long dreamed of designing Hi-Ho Cherry-O: The RPG, that niche remains wide open.

If you want an example of a truly independent game, take a gander at Braid, created and funded by a single programmer over the course of three years. Like Portal, the game takes a familiar setting—in this case, the “platform jumper” epitomized by Super Mario Bros.—and introduces a bizarre twist: The protagonist must manipulate time in a variety of ways to solve puzzles that would otherwise be impossible. Portal and Braid are peas in a headache-inducing pod, screwing with your conception of topology and chronology respectively.

Indie games are a hot topic at PAX this year, with a bevy of panels and demos on the subject. The PAX 10, a collection of the most eagerly anticipated video games from small or one-person studios, includes a game in which you can copy environmental elements (e.g., doors) and then paste them into other places where they will become useful (Snapshot), a game in which a protagonist from the second dimension explores the third (Fez), and a game set in non-Euclidian space in which simply figuring out how the universe works is a primary goal (Antichamber). These are games in which the main selling point is not the brand or graphics or length, but the idea—an idea so compelling that someone devoted months or years of their life (and a hefty chunk of their savings) to bring the game to life.

Roleplaying games are undergoing an indie revolution as well, as Fiasco illustrates. While traditional RPGs have a collection of rules that would make Hammurabi proud, a focus on dice-rolling, a single game master who serves as bene-/malevolent dictator, and campaigns that can outlast a presidential administration, Fiasco provides a loose framework in which all players collaborate on creating a narrative similar in theme and duration (two hours) to Blood Simple or Fargo. The game was designed by a single person, and is obtainable at a reasonable price thanks to the convenience of PDFs and print-on-demand technology.

The indie movement is the latest manifestation of the DIY ethic so prized by gamers. Computer gamers write mods—modifications—for their favorite titles, or use editors to create and distribute new levels. Board gamers introduce house rules to tailor a game to their liking. Players of miniatures painstakingly paint their figures. And improvisation is the heart of roleplaying.

More than anything, gamers celebrate community, and that has always entailed not only playing games but creating them.

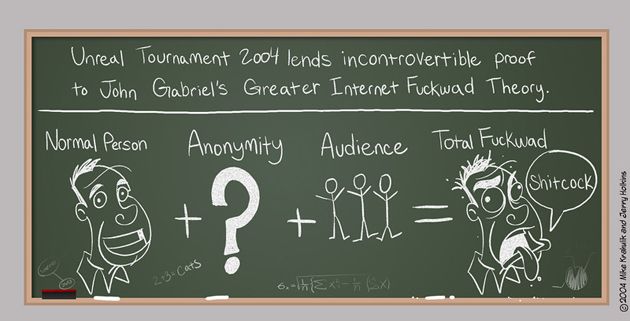

In 2004, Penny Arcade articulated the Greater Internet Fuckwad Theory:

Evidence for this hypothesis is rampant on the web, nowhere more so than on video game forums and the gaming networks to which PlayStations and Xboxes allow access.

Given that, you might therefore expect an event like PAX, a convergence of video game players in a reality of the non-virtual kind, to look something like the Battle of Stirling Bridge, with homophobic slurs taking the place of lances.

But, no. Drop the “anonymity” from equation above and you’re left with the nicest bunch of 70,000 people you are ever likely to encounter. Over the three days of PAX I am welcomed into pickup games. I chat with the people next to me in lines about the rising prominence of deck-building in board games. When I walk into the video game free-play room and confess to having no idea what to try, those around me blurt out their recommendations with an enthusiasm bordering on zeal.

And here’s a fun fact: Over the course of the convention the Cookie Brigade raises $15,000 for Child’s Play, a charity launched by Holkins and Krahulik that supplies children in hospitals with toys and games. They do this by giving away pastries and asking gamers for voluntary donations. The next time you log on to the Call of Duty servers and are immediately shot in the head by a 14-year-old “teammate,” take solace in imagining that he chocolate-chipped in.

Mike Krahulik addresses the two remaining Omeganauts. “We’re going to do something,” he intones, “that we’ve never done before.”

It’s the PAX capstone event, and there’s a bitter irony to the matchup. Nerdgasm stands on the stage of the Paramount Theater this Sunday evening because he was paired with FluffyBunni during Portal 2, the latter’s intimate knowledge of the levels compensating for the former’s brief exposure to the game. Now his erstwhile teammate is all that stands between him and an all-expenses paid trip to Japan for the 2011 Tokyo Game Show.

But this is no time for sentimentally. This is the Omegathon.

“That’s right,” Holkins says, continuing where Krahulik left off. “Each of you must choose one of the fallen Omeganauts to be your spirit animal!”

Nerdgasm does not yet know what he will be playing, so a strategic choice is not possible. He instead pays off his debt to Portland, which trained him in his time of need, and points to Ainsmar, fellow citizen of his hometown.

Krahulik and Holkins ask the audience to predict the final game as Ainsmar sprints onto the stage. She high-fives Nerdgasm with such velocity that it is audible over the shouted-out guesses.

Ping-Pong is suggested and shot down. “That’s a condiment,” Holkins says in response to someone’s speculation.

A moment later, the curtain lifts to reveal two video games. But no one in the audience can make out what’s on the screen, and the identity of the final Omegathon event remains opaque. Until...

♫ Doo doooo. Doo doo doo-doo-doo ... ♪

The crowd goes wild.

“It’s the Legend of Motherfucking Zelda,” says Holkins.

I whoop along with the rest of the crowd, while thinking: This is a terrible idea for an Omegathon event!

The Legend of Zelda is considered by many to be the first roleplaying video game. As such, play consists of wandering around villages, chatting with townsfolk, crossing the globe in search of treasure, and delving deep into dungeons. All of which takes a long, long time. For a moment I wonder how long I will be sitting here, watching Nerdgasm collect coins to buy a helm.

But there are two twists that make this competition workable. First, the players only need to arrive at the first major milestone of the game. Second, each player’s spirit animal is given a sheet of paper, providing step-by-step instructions on how to get there.

The crowd counts backwards from five, and the questing begins. Although Nerdgasm was two years old when The Legend of Zelda was released in 1986, he knows what to do first: Enter the cave, talk to the old man, get the sword. Tips like this are passed down modern generations like advice on childbearing was in the 1800s.

Ainsmar consults the walkthrough, and tells Nerdgasm where to go next. As play continues, the Penny Arcade guys offer tips and commentary. “East and West are two different directions,” Holkins explains to FluffyBunni at one point. “That’s a lot of bats,” Krahulik opines at another crucial juncture.

Four minutes later Nerdgasm defeats a dragon, enters the final chamber, and is declared the winner of the 2011 Omegathon.

And so PAX ends, for another year.

Afterward I meet a dozen friends at the Six Arms, some of whom I’ve known for years, some of whom I met during the event. We talk about what we played over the weekend. We talk about upcoming releases. We talk about flying across the nation to attend PAX East next spring.

We talk about games. And Penny Arcade. And, of course, Wil Wheaton.