The Lost Memory of Skin, Russell Banks’s 17th book, was the occasion of our sixth gabfest. Our string of conversations began in the early ‘90s, when we talked around the publication of his bracing and harrowing novel, Affliction. If you are unfamiliar with Banks, Affliction and another of his novels, The Sweet Hereafter, were made into well-admired motion pictures.

In this installment of our never-ending conversation, Banks and I talk about the Kid, the new novel’s protagonist, who is a convicted sex offender; Dolores Driscoll (from The Sweet Hereafter); making movies; Rule of the Bone; the great Nelson Algren; obsessive love; Treasure Island; Rolling Stone’s Matt Taibbi; and Banks’s feelings about the state of the union:

“I’m deeply depressed. And pessimistic. At this point, pretty fearful. Realistically fearful that our next president will be Mitt Romney. And that there will be even more assholes in Congress than there are today. And the corporate interests in America will have an even deeper influence on policy… We’ve become a plutocracy.”

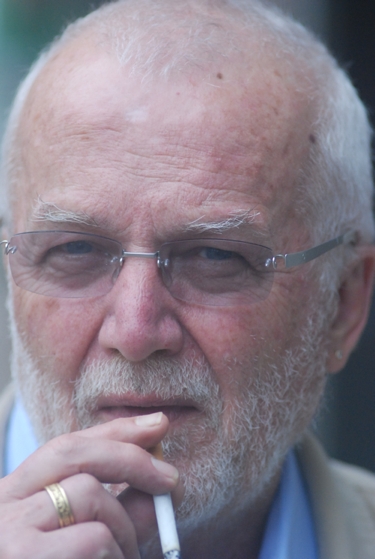

Robert Birnbaum: This is your 17th book.

Russell Banks: So it seems.

Birnbaum: Did you think you’d write so much?

Banks: No, who’d a thunk it? I mean, I started in a couple places being introduced that way at readings—the 17th book or whatever. Jesus, I guess that’s a shelf now (laughs). Someone said you’re not a writer until you have a shelf (laughs).

Birnbaum: Who said that—someone with a shelf (both laugh)?

Banks: Yeah, of course.

Birnbaum: Like saying you’re not a successful writer until you win a Pulitzer—only said by people who have one. Does it get any easier? Is it easy?

Banks: It doesn’t get easier. And I don’t think I want it to get easier. I’ll tell you—the difference from my 20’s, 30’s, and now in my 70’s, some things are different and some things are the same. The things that are the same have to do with not knowing what I am doing. I still don’t know what I am doing. When I sit down and start writing I don’t know any more about what’s happening in the page then I knew when I was in my 20’s. The difference is that I trust that a lot more than when I was in my 20’s—that’s the process. That’s necessary. When I was in my 20’s I was scared of that. And I’m not scared of that. In fact, now I am afraid of knowing too much. And I try to do something every time out that I don’t know. That’s going to push me out beyond what I know. My mentor, an early sponsor in a sense, was Nelson Algren, the novelist.

Birnbaum: I grew up in Chicago. Algren is well known to me.

Banks: He’s like a god out there. He was a heroic figure to me in my 20’s. And in my 30’s too. We stayed pretty close over those years. He used to say, “A writer who knows what he is doing doesn’t know very much. Remember that.”

Birnbaum: Nunnally Johnson said something like that—“only hacks are consistent.” So what do you begin with?

Banks: It varies quite a bit. I probably can’t get rolling until I have a character that I have organized my emotions and affections around. And my sympathies. But like with this book, The Lost Memory of Skin, I know what I started with because I can remember very clearly being drawn into the material. I spend six months a year in Miami Beach and look out over this causeway, the Julia Tuttle Causeway that connects the beach to the mainland. About four years ago articles started appearing in the Miami Herald and other papers about a colony of convicted sex offenders who were living under this causeway. I could see the causeway from my terrace, and these were guys who by law couldn’t live within 500 feet of where there were children—so the unintended consequences of good intentions.

Birnbaum: Sounds Draconian.

Banks: Of course it is. I knew down there, there were psychopathic serial rapists and pedophiles right alongside some poor old drunk who got busted for indecent exposure because he was peeing in a parking lot, or some kid who had sex with his high-school girl friend, who was under 18, and got statutory rape. They were all, post-imprisonment, stuck together and living down there. So that situation kind of opened up first for me. Then I started thinking about the whole larger context—the digitalization of sex, the plethora of and inescapability of pornography on the Internet especially. And how we view sex crimes in general as a culture—how panicked we are over it especially regarding children. So in a way the context arose before any characters did. But I still wasn’t writing about it or thinking I would write about it. I was following my own social political curiosity. But then I began thinking about a kid living down there. It could be a dumb younger cousin or the kid that lives down the block. And I could easily imagine a kid, naïve and isolated and ignorant, who barely got through high school. Illiterate—no skill set. No anything except running his computer and surfing the net for porn sites. And the Kid [the main character of Banks’s novel—ed.] arose out of that. Once I had the Kid then I want to know what the story of the Kid is. Where did he come from? Where’s he going? And then I could begin the novel. That’s not typical. In other cases I have had the character first. Like in Cloudsplitter I had John Brown. I knew I wanted to write a novel about John Brown. The Darling—I had the character of Hanna Musgrave doped out. But I got there by getting involved and interested in chimpanzees. Who would have thought—it’s just whatever door opens up and takes you into a fictional world. It can vary enormously.

Birnbaum: Did you actually go down beneath the causeway?

Banks: Oh yeah. These guys weren’t scared of anyone coming in there. They had been dropped there by the city law enforcement and they were happy to talk to anyone who wanted to talk. Which are not very many people. Most people didn’t even want to think they were there. Journalists—that’s about it. A couple lawyers, human rights activists were down there. There was a lot of special pleading—you know, excusing themselves and blaming others—”I never did anything wrong,” etc. But they all were accessible. I didn’t investigate it the way an investigative journalist would—tape record interviews and go through that process. I was interested in it from a novelist’s point of view. I wanted to know what it smelled like. What’s it like with the sound of trucks and cars and motorcycles rumbling overhead 24 hours a day. You know, the dark, damp light down there, the bay creeping up as the tide rises, going back down—the whole sensual details of the place. The rest of it I could get by research online or in books or whatever—there’s plenty of information on this stuff once you get into it. The legal, psychological, historical, sociological aspects of it—it’s all out there; there are plenty of people who have dedicated their careers to it.

Birnbaum: When we talked about Rule of the Bone—you joked that people would say, “another bummer from Banks.”

Banks: (laughs)

Birnbaum: What could be darker than this subject? Somehow it doesn’t read as darkly as Affliction or A Sweet Hereafter.

Banks: It’s not as claustrophobic.

Birnbaum: It is a most troublesome subject. The Kid was as much a victim as—

Banks: Yeah, in a way he is.

Birnbaum: He wasn’t a predator.

Banks: No—a dumb kid. Sexually confused. Alienated. Lots of things. Not angry. Basically an honest kid. Trying to figure out how to be a good person. Not very well equipped to do that. An abandoned kid, essentially. Benignly neglected. The mother takes credit for provided him with shelter, food, and an iguana. He’s a feral child in a way. You have an awful lot of them out there. Latchkey kids we used to call them. One parent—she’s working all day. Comes home then goes out at night, and she’s still a child herself in some ways. It’s a country that has fewer and fewer adults in it.

Birnbaum: I have often wondered if my parents’ generation was prepared to have children. Now I am thinking that current generations may be less equipped. The affluent parents rely on surrogates, and the ones that aren’t rich have feral kids.

Banks: You’re right. We have an economy now where both parents have to be out there working and don’t have any way to take care of their kids—no childcare that is structured and protective, trained. We have ended up abandoning the children. And it’s normalized. Parents in their 30’s, 15 years ago they were children. In 1998 they were kids. So this social circumstance has really been normalized now. And as you say, those who can afford it, they have nannies, this that and the other.

We have an economy now where both parents have to be out there working and don’t have any way to take care of their kids—no childcare that is structured and protective, trained. We have ended up abandoning the children. And it’s normalized.

Birnbaum: And they are fast-tracking their kids in private schools—

Banks: Exactly.

Birnbaum: And what does that mean to their kids?

Banks: I know—they are just feathers in their parents caps in some ways.

Birnbaum: Fashion accessories.

Banks: The Kid, who was always looked upon as a runt, comes to life with engagement. Everybody who deals with him—a native intelligence is revealed. A survival instinct. A sense of humor.

Birnbaum: I was troubled by his passing up the chance to stay in “paradise” and returning to the colony.

Banks: Well, you know, one of the running themes in the book is the difference between guilt and shame. Early on he doesn’t make a distinction between them. He is guilty because he broke the law and the law won. He knows that, but he has internalized society’s view of him as a convicted sex offender. The guy at the registry whose face pops up when he goes to the library. So he is ashamed of himself. Gradually he learns to make a distinction. Partly through the agency of the professor and telling his story and getting a coherent narrative established for his own life story. In a way he becomes a more existentially controlled person. A man who accepts his fate and achieves though that some sense of control of his destiny. And by the end he has rejected being ashamed. He is not ashamed anymore. But he knows he is guilty. And he knows he has to take his punishment. He goes back there but he really doesn’t know why he is doing it. It’s really an existential choice when he says to Dolores, “You take the dog and the parrot—Einstein and Annie.” He was exercising responsibility toward them. “I’m going back; that’s where I belong,” he tells the writer that. But he’s made that choice. He’s not avoiding his responsibility. I couldn’t let him off the hook. I got to that point in the book, right near the end, I had to make a decision—a very hard one. Either keep him out there in the swamp in a nice little setup—the people there kind of like him, nice people, and he has his dog, his parrot. Or do I say, No, I can’t let him off the hook. He did try to have sex with a 14-year-old girl. And he knew it. He knew what he was doing. We understand why he did that. But we can’t make the fact that he did that go away. I had him absorb that himself. That’s his truth, his bottom-line truth. He doesn’t think he can articulate it at that point and he doesn’t. He just makes a decision. The writer asks why is he doing this—Dolores asks why he is going back. And he answers, “That’s where I belong.” That puts the onus on the city—do the sex offenders really belong there?

Birnbaum: This would be the first indication that he has a sense of future. He is looking toward the end of his parole.

Banks: Yeah.

Birnbaum: Nine years hence he will be 30, and he now sees there is something beyond that. Another life.

Banks: Exactly. That’s that long litany at the end—in nine years I’ll be this that and the other.

Birnbaum: I liked the characters you had over in the preserve by the swamp. Dolores was especially sweet and understanding. Do you know someone like that?

Banks: Yeah. Her name is Dolores Driscoll and she’s in The Sweet Hereafter. She’s the school bus driver.

Birnbaum: Wow.

Banks: I always wondered what happened to her. I felt badly about the way that book ended for her. (Both laugh.) I had to give Dolores a second chance. She’s a real nice person.

Birnbaum: Might you revisit the Kid’s story?

Banks: Down the line? There were only three characters I ever wanted to revisit before. One was Dolores Driscoll, because at the end of The Sweet Hereafter she really ends up in a bad place through no fault of her own. She becomes the scapegoat for the town after the school bus accident. She is ostracized, exiled in the same way the Kid is exiled from his world. I think that connection is strong. And the other two are adolescents—Nicole Burrell in The Sweet Hereafter, in the wheelchair. Because she’s an adolescent. I liked her—she was tough and strong and angry. And I thought, “Boy I’d really like to run into her when she is 30. I’d bet she’d be really interesting and smart and so on.” And the other is Bone himself from Rule of the Bone. I’d love to know what happened to him down the line. To see what kind of man he turns out to be. The last we see him he is sailing off to the Caribbean when he is 15 years old. Those two are adolescents and I can see why I would want to see how they turn out. I just wanted to make it up to Dolores (both laugh). Let her go south for the winter—no more of those Adirondack winters.

Birnbaum: Do you keep all your characters in some kind of accessible place?

Banks: A lot of them do keep floating around in my mind. Unless they die at the end.

Birnbaum: But you haven’t brought someone back before, have you?

Banks: I don’t think I have.

Birnbaum: Why haven’t you—because it seems like old news?

Banks: Partly that. It’s territory where I know how their lives ended or turned out. And they don’t raise questions for me. Dolores did, and Bones and Nicole do for other reasons. The Kid here does. I’d like to revisit the Kid at 30 when he is finally out after having lived down there. I know what happened to the guys down in Florida—the actual community. They moved them out of there and put a chain-link fence around it. Tried to house them for a while in motels with the city paying. And then people at the motels started complaining, even though these were really ratty little motels. So they moved them even further out of the city into a trailer park. So there is still this cluster of convicted sex offenders in the same community. They just moved it so it wasn’t quite as unsightly. But it’s essentially the same situation.

Birnbaum: Is Debra Granik (Winter’s Bone) going to direct Rule of the Bone?

Banks: Oh yeah, she’s exactly the right sensibility. So we are working together. I am executive producing it with her. They are looking at locations now and trying to cast it this fall. Hoping to shoot in the spring. They have raised most of the money.

There are still good movies made. But with difficulty, and you have to set out to make that kind of movie. You can’t go out with any illusions that you are going to go to work with a studio and you are going to make a movie you like or can admire or respect.

Birnbaum: What about Continental Drift?

Banks: We tried. It gets blown up and then collapses and [the producers] back off. It’s just too dark and grim a story. Every time we get close to it they realize that (laughs), they say, “Wait a minute is there any way we can make this about Cubans?” (laughs) “Do we have to make it about Haitians?” And, “Can they all live?”

Birnbaum: Those anecdotes remind me of what is probably apocryphal—MGM wanted to buy the rights to one of Richard Wright’s novels but asked if he could make the protagonist white (both laugh).

Banks: Exactly. We are going to do The Darling with a French-Canadian director named Denis Villeneuve who did a movie last year called Incendies that won a lot of awards. He is really wonderful with Jessica Chastain as Darling. Originally Cate Blanchett was going to do it—actually she is getting a little older for it now. I wrote the screenplay for that.

Birnbaum: So you’re busy?

Banks: Yeah, not retired yet.

Birnbaum: You split your time between north and south.

Banks: I get as close to the borders as I can so in case I have to step across I can get off real fast to Canada or get out real fast to Cuba or wherever.

Birnbaum: Have you been to Cuba lately?

Banks: I went down in 2001 and again in 2003.

Birnbaum: What does this period of time represent for you? Do you compartmentalize—a movie period, a writing period?

Banks: I must in some sense. I kind of have to. But I don’t really in the sense that when I am doing one thing I am not aware of the other. The film work tends to come in spurts. Some very intense work for a few weeks—sort of like binge work. Then it’s over and I don’t think about it; there’s nothing going on for the next five weeks or two months or whatever while other people do their thing. In the meantime, I always have a book going that I am working on but I can pull away from for a couple of weeks and do something intense with a screenplay. It’s a different kind of labor.

Birnbaum: Given the collaborative nature of film, how much do you listen to other people when writing a script?

Banks: It depends on who you know. There are people I really trust on each of these projects. I really trust Debra and her sensibility and her skills. And I really trust the director Villeneuve. Two weeks ago he is up in Montreal, he wanted a meeting with the person who he had worked with on his previous screenplay to go over my screenplay. So I went up there and we sat around all day with this woman who is really good and really smart and loved the book and loves him. And did a day-long critique of the screenplay which resulted in some really big improvements. That came mainly from her. So—you have to do that. But then there are other people. Like studio executives or agents or whatever—they are not interested in making a good movie. They are interested in making money on their money—”I’m putting in 15-20 millions dollars, I want to make sure I’m getting it back.”

Birnbaum: You seem to be one of the few writers of fiction who are not totally turned off by the film business.

Banks: There are still good movies made. But with difficulty, and you have to set out to make that kind of movie. You can’t go out with any illusions that you are going to go to work with a studio and you are going to make a movie you like or can admire or respect. You have to know that if I do this, I have to do it down and dirty and do it with really serious people, and the budget is below a certain figure, and we don’t hire any movie stars whose egos dominate the whole damn production. We don’t drive the budget so high that the studio executive is going to come in and watch every move. The director needs to have final cut—things like that. Well, if you want the director to have final cut then you know the budget has to be below a certain figure—unless the director is Marin Scorsese. And even Scorsese doesn’t have final cut. I watched him at one point, and we’ve worked together on different things over the years. I watched him when he was finishing up Gangs of New York and how the studio executives were all over him—cut this, cut that, too long, yada, yada yada. So even he doesn’t have that.

Birnbaum: What are the film prospects of The Lost Memory of Skin? Can you see that being a movie?

Banks: No. The material is just too dark and too scary. But I was in LA and met with the agents at CAA, and the one agent I trust there and really like and have worked with for a number of years is Jon Levin. He had a really good idea—it should be a David Lynch-like series for HBO. The Kid is scary but not scary. Reassuring, and he is an easier way into this world. You have characters like the Professor and the Shyster and poor old Rabbit—an interesting battery of people. And then you go out into the swamp and do a really David Lynch thing. I said, “Fine, you do it. I don’t want to.”

Birnbaum: The premium cable channels have certainly provided wider possibilities for writers.

Banks: Exactly. There are things you can do on TV that you cannot do on film. And now actors, first-rate actors, are willing to do TV.

Birnbaum: As well as writers, The Wire being an example.

Banks: That the Richard Prices and people like that are writing for. Frankly, I thought that was as good a thing as one could hope for.

Birnbaum: Are there books you have read that you would like to make into a movie?

Banks: Yeah. I would like to make a movie that lies behind this one book. It’s already been done in the past. But I’d like to make a really adult movie out of it—out of Treasure Island.

I am climbing in the Himalayas in April. It’s on the short list of things to do before I die. I am not going up Everest, but I do take a trek and climb once a year.

Birnbaum: Hmm. A novel was just published by Sara Levine, who teaches writing at The Art Institute of Chicago, based on Stevenson’s classic: Treasure Island!!! The protagonist in the book picks up Treasure Island and the book becomes central in her life.

Banks: Really. Well, it’s the book that lies behind this book. I realized I had this kid who was not quite an adult but not a child, who was innocent but not really innocent. And then I had this older man who is physically odd—he has both legs but he is odd. And he is both custodial and protective but also slightly menacing. And I said, Wait a minute, there is something like this, I know I read it when I was a kid. It was Treasure Island. I went back and reread it. What a hell of a book—that’s a beautiful book.

Birnbaum: The movie version was made by Disney, right?

Banks: Yeah.

Birnbaum: So it was really sort of—

Banks: Soft. It was very soft. The novel is much harder than that—much more violent. It’s a tough novel. And the character Long John Silver is menacing, and there are other characters there that are really scary. But it’s so well written, and all this business with the treasure—it’s full of archetypes. It’s an ancient story: searching for buried treasure.

Birnbaum: I could see a studio biting. Just look at the four or five Pirates of the Caribbean. “A pirate movie, let’s do it!” (both laugh) You’re full of ambition.

Banks: (laughs)

Birnbaum: Is there something you want to do that you haven’t done?

Banks: I am climbing in the Himalayas in April. It’s on the short list of things to do before I die. I am not going up Everest, but I do take a trek and climb once a year. I have never done the Himalayas. I really want to do it. There is a great route there they call “The Three Passes.” which gets you up to about 19,000 feet or so, and it’s a long 20 day trek. A magazine got in touch with me [Men’s Journal]—”We want to upgrade a little bit and get some literary writers.” I know they want to become Esquire or whatever and somehow compete in that market. “So we’ll send you anywhere you want to go—do an adventure of some sort.” I said, “OK, this is what I want to do.”

Birnbaum: Men’s Journal published one of my favorite pieces of nonfiction by Jim Harrison about the Mexican-US border back in 2003. It was a surprise to find him in that venue.

Banks: There are a couple of editors over there—it’s owned by Jann Wenner—any expensive decisions they put off to him. They had to do that with me—this is an expensive trip. And they’re sending a photographer along. It’s a big deal. Rolling Stone published some of the best writers of our time, the previous generation as well.

Birnbaum: Simon & Schuster is coming out with a large Hunter Thompson anthology, and Johnny Depp’s Rum Diary is coming out. Matt Taibbi is great.

Banks: He’s very good. He was very good on Goldman Sachs. He was great on the 2010 elections.

Birnbaum: His anthology Griftopia is entertaining and infuriating reading, including the Goldman Sachs piece. I wonder why there is this diminution of these kind of oppositional voices. Who is paying attention?

Banks: Where are you going to publish them now? A lot of those bright guys coming up ended up on the Internet. They are writing blogs and stuff instead of the really serious investigative journalism that Taibbi does. And others do—Chris Hedges and a few other people.

I am 71 years old. I have been madly in love, you know, at least three times. Possibly four. But enough so that I was certifiably insane for a brief period. And I have never really written about it.

Birnbaum: Chris Hedges seems to be getting more and more outraged.

Banks: He’s so angry. He is sputtering on the page (both laugh).

Birnbaum: I started to notice him when he was booed at Rockford College for giving an anti-Iraq war speech. He seems to be getting more shrill, for lack of a better word.

Banks: Strident. I know him and recently saw him at a big book party in New York. He had just come breathlessly up from Occupy Wall Street—of course he was down there (laughs). But he was one of the first national journalists who was covering it, and he was covering it right away. For Huffington Post or someone like that.

Birnbaum: Maybe Truthdig.

Banks: That’s right, and also AlterNet.

Birnbaum: That’s an informative site. Good stuff.

Banks: That’s where in the past a lot of the people who would have been at Rolling Stone or Esquire or Harper’s are. Most of those magazines now are pretty boring.

Birnbaum: True dat. What do I look at these days? I just look at news aggregators. And the Daily Beast where I occasionally contribute. Speaking of which, I wrote on some recent debuts including Frank Bill’s Tales of Southern Indiana. Heard of him?

Banks: No.

Birnbaum: Meth, incest, murder, all sorts of low-life mayhem.

Banks: Sort of like a Donald Ray Pollack kind of world.

Birnbaum: Exactly.

Banks: He’s really good. I like him.

Birnbaum: And the world that Daniel Woodrell writes about. I thought it was an amazing trick that the film of Woodrell’s Winter’s Bone made the Ozarks seem as foreign as Afghanistan.

Banks: Yeah, that’s America—that’s out there. They are doing that in upstate New York where I am. The same kind of clannishness. We had a murder up there two years ago that grew out of making meth and its distribution. Everybody knew it. But nobody would talk about. It was declared a suicide and that was the end of that.

Birnbaum: Did you know a writer who passed on recently—Joe Bageant? His last book was called Rainbow Pie: A Redneck Memoir. Also wrote a book called Deer Hunting with Jesus.

Banks: No.

Birnbaum: He’s dead-on talking about the invisibility of the white underclass in America. Who speaks for those people?

Banks: They remain kind of cartoon figures in the popular imagination.

Birnbaum: That FX series Justified gets into that—Harlan County, Kentucky.

Banks: Maybe I can get it on Netflix.

Birnbaum: So, what’s next? Besides finishing your book tour and your trek?

Banks: Then I am heading down to Miami. I want to hole up. I have a novel I want to write. I hope for it to be—I mean for it to be a short novel, 150 pages.

Birnbaum: Why don’t you call it a novella (both laugh)?

Banks: Yeah, I know. I could call it Fred (laughs).

Birnbaum: I don’t know what a novella is.

Banks: I don’t either.

Birnbaum: Except that Jim Harrison writes them.

Banks: A short novel about obsessive love, the madness of love. I have never written about it. I am 71 years old. I have been madly in love, you know, at least three times. Possibly four. But enough so that I was certifiably insane for a brief period. And I have never really written about it. I am old enough now to have some detachment, some distance on it. If I get madly in love at this age it will just look like a dirty old man, or some kind of weird obsessive dementia. I don’t think it’s going to happen. So I feel like I should try to write about it—should go there.

Birnbaum: To quote Fats Waller, “One never knows, do one?” (both laugh) Want to talk about your feelings about the American political scene?

Banks: That it’s gone to hell in a hand basket? That we have become a plutocracy?

Birnbaum: When I said feelings I was looking more at optimism or pessimism.

They come in with such authority, these guys. And speak with such authority. The assumption is that they know and you don’t. What do you know? You’re just a guy with a law degree who worked as an organizer and a second-tier professor and then a senator; you gave a good speech. You don’t know shit.

Banks: I’m deeply depressed. And pessimistic. At this point, pretty fearful. Realistically fearful that our next president will be Mitt Romney. And that there will be even more assholes in Congress than there are today. And the corporate interests in America will have an even deeper influence on policy—of course they are shaping all our policy, it doesn’t matter what it is. Any reform. You want national health Insurance? It turns into a boondoggle for the pharmaceutical and insurance industries. Reform the tax code? We’ve become a plutocracy. I am very pessimistic about the long run. Small cosmetic fixes here and there are going to occur pragmatically. We will probably not invade a country like Iraq again—at least in my lifetime. But you never know.

Birnbaum: We’ll do it with drones. I was reading Ron Suskind’s Confidence Men and was interested to note that despite President Obama’s good intentions he was overwhelmed by the situation he inherited.

Banks: Yeah.

Birnbaum: And he ended up punking out by hiring guys like Geithner and Summers. The same guys—

Banks: Who put us in the basket. He didn’t punk out in the same sense. He came in there insufficiently skeptical. Naïve is another way to say it. He wasn’t wise in the way of Lyndon Johnson, who knew these were bastards—every one of them. Or even Jack Kennedy. Even he knew what bastards they were—Because his father was one (laughs). He knew they were gangsters in suits. And Nixon knew they were gangsters in suits. Carter didn’t. Carter thought good intentions would do it. I think Clinton knew it too.

Birnbaum: Clinton is a slick guy.

Banks: So he knew they were slick. But Obama came in and didn’t realize it—how really tough these fuckers are.

Birnbaum: He assumed that Larry Summers’ Harvard credentials somehow purified him.

Banks: Exactly. He was impressed by that too. Summers was Secretary of the Treasury in the past. They come in with such authority, these guys. And speak with such authority. The assumption is that they know and you don’t. What do you know? You’re just a guy with a law degree who worked as an organizer and a second-tier professor and then a senator; you gave a good speech. You don’t know shit. Well, I am sure there are days that [Obama] thinks that’s true.

Birnbaum: Watching the Republicans debate—to think of any of those people as a future president is too much to consider. What happened to people who can make a good claim to fitness for public service? People who, while they were filling their pockets, also aspired to do good (both laugh)?

Banks: They live in bubbles. I think they believe their own shit. They really do eat the same stuff that they say. And they internalize it and believe it. And they have flaks around them that tell them it’s true. “You are really doing a wonderful thing. The country needs a businessman.”

Birnbaum: At least Gail Collins will never let the world forget that Romney drove to Canada with his family dog on the roof of his station wagon. (Both laugh).

Banks: She did it again today, I saw.

Birnbaum: Some people would say this is the way it ever was.

Banks: It was never this bad, at least in my lifetime. The power of these financial institutions is so immense, candidates can’t run for office without it. We are going to have a billion-dollar campaign on each side. That’s a two-billion-dollar campaign. When you have to go out and raise that much money, where are you going to go? Who has that much money? Not from 10-dollar contributions.

Stories are what connect us to each other, face-to-face. When you read a novel, whether you hear it on an audio tape or see it on a Kindle, you are seeing the world through the eyes of someone other than yourself. You are inhabiting another human being. It’s a deeply personal encounter.

Birnbaum: Well, at least the campaigns create jobs (both laugh). Posters, buttons, copywriting, catering, hotels. I just read a book about India by Siddhartha Deb (The Beautiful and the Damned: A Portrait of the New India). Want to talk about dysfunction, corruption, and plutocracy—oh my. He described a situation where nearly 200,000 farmers killed themselves because of a reneged-upon government policy. A nation of 700 million impoverished people. What is the big miracle there?

Banks: Yeah, right.

Birnbaum: Deb divides India into high context/low context. The former is out among the real India. The latter is when you live in gated communities emulating American life.

Banks: We have more and more of that in this country also. That is partly the focus of this book. I say don’t forget there are other contexts—there is another world here. And it’s not just some peculiar colony under a bridge. It’s all over the fucking country. We are going to have to face it. Deal with it.

Birnbaum: Does it strike you that the digitalization of our society has sapped it of a huge vein of compassion?

Banks: It’s alienated people from each other. Take away face—to-face communication, contact with people, and you end up living in a kind of cell. An envelope that is only you and your iPhone and your Facebook friends—no give-and-go that human contact requires, where compassion grows. Compassion comes from human contact. It doesn’t come out of statistics or numbers or reports—even journalism. It comes out of human contact. Personal contact. When people started admitting they had gay people in their family, then they could say, “Maybe gay marriage isn’t so scary.” My wife’s family, everybody’s favorite uncle, her mother’s brother—he was with another man all his life, and nobody in the family would ever admit he was gay. He was closeted his entire life. Now when the next generation came out, the family had to recognize that someone in their family whom they loved was gay, they had to look at it differently.

Birnbaum: How did it affect the uncle?

Banks: It kept him depressed most of his life. And thwarted all his relationships with his family, with people he loved. Probably drove him into a kind of sexual ghetto. He lived in San Francisco—a Connecticut Yankee having to go to San Francisco to not be lonely. But to get back to the question, the digitalization of our social encounters does deeply affect our capacity for compassion. I really do think so.

Birnbaum: I would like to think that people who read are keeping alive a certain sense of humanity. But then what about e-readers (laughs)?

Banks: That’s OK. It’s still story. Stories are what connect us to each other, face-to-face. When you read a novel, whether you hear it on an audio tape or see it on a Kindle, you are seeing the world through the eyes of someone other than yourself. You are inhabiting another human being. It’s a deeply personal encounter. It gives meaning to someone else’s subjective experience, a single person’s experience. That’s a different kind of experience than a movie allows. A movie—you don’t interact with it, you just accept it. It takes you over like a very powerful drug. Story is a different thing and there are many delivery systems for story.