The City Is Wilder and Kinder Than You Think

Situationist invades Hoxton... Street poems arouse Londoners... Public discourse colored by disfigured Futura... Robert Montgomery’s street poems have something to say to you.

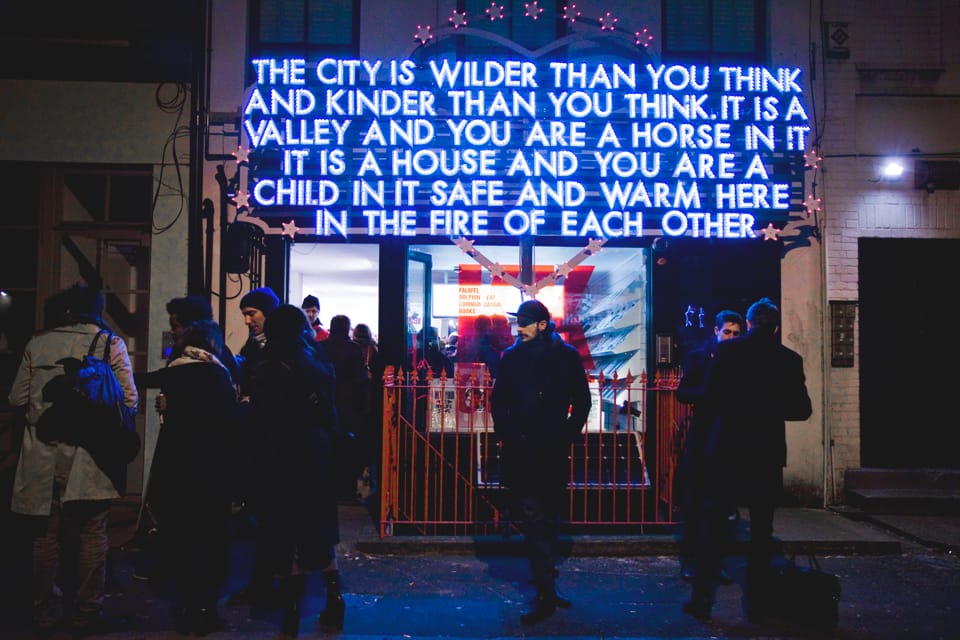

Tucked away in an otherwise dim pocket off London’s Old Street, a short poem hangs from a building’s facade and shines in the night sky. The poem is constructed of wood, solar panels and 12 volt LEDs. It radiates the light it has recycled from the sun. A small crowd stands beneath it, smoking cigarettes and talking in the cold February air. A larger one moves and shifts slowly behind them, in and out of the narrow room inside. People sip wine from glasses and drink beer from brown bottles with red and white labels. Music and poetry paint the walls.

It’s the opening night of artist Robert Montgomery’s gallery show at KK Outlet in Hoxton. And while some of his work hangs right here—inside the narrow room, up on the building and off into the night—his three most significant pieces are hanging under an overpass just a short walk up the street. Like billboards. Only different.

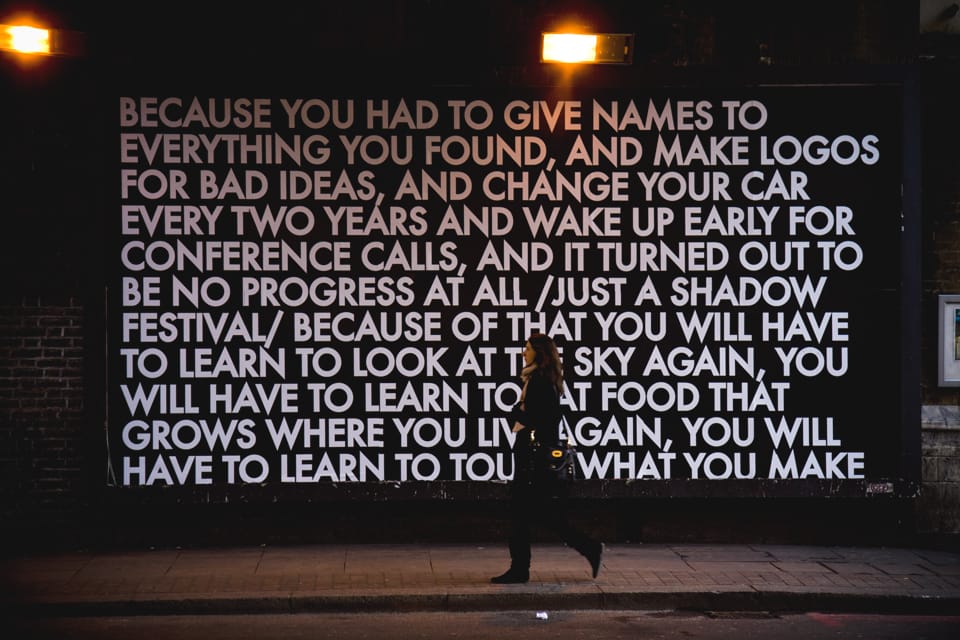

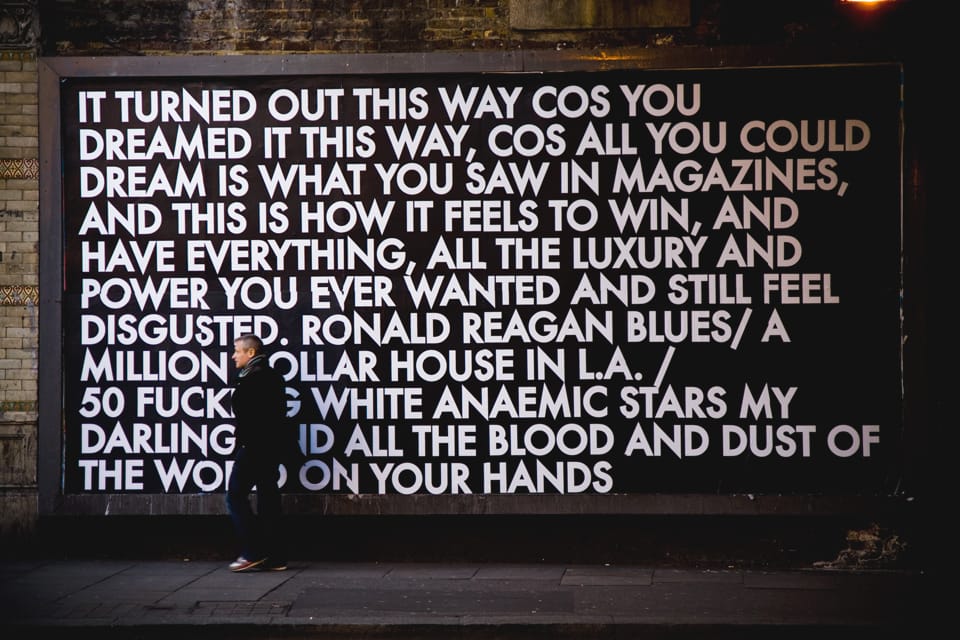

The poems on Old Street are set in capital white letters on a brushed black background, in a sort of mangled Futura; it’s a type treatment that should send his words running and screaming through the streets but somehow does not. Instead, the words lean calmly against the wall and arouse a kind of subtle and unnoticed reflection. People pass by on their way to or from here or there. They do double-takes and slow down. Intrigue wraps their faces. They stop, read, think, and eventually move on, carrying something with them that maybe wasn’t there before. Something that came free, silent and unexpected, set in capital white letters on a brushed black background.

“You will have to learn to look at the sky again, you will have to learn to eat food that grows where you live again, you will have to learn to touch what you make.” Just like that. With no placard to explain. No final punctuation to finish the thought.

“I’m an acolyte of Situationist ideas,” Montgomery says, referring to Situationist International, a group of 20th-century European revolutionaries who used public art installations to capture people’s attention, ask questions, and express ideas. “Their influence on me is far reaching. But the key introductory idea is perhaps Guy Debord’s idea of the spectacle, by which he means loosely the coalition of capitalism and the media.”

Debord, a French social theorist, writer and filmmaker, helped to form the SI in 1957. In his influential book, The Society of the Spectacle, he suggests that the combination of capitalism and the mass media will lead to a society dominated by false images, and that these images will act as a spectacle isolating people from reality. Debord eventually shot himself through the heart in 1994 in a small village in Auvergne, France.

“What Debord and the SI really get into,” Montgomery says, “and what sets them apart from much other post-Marxist thought, is questions of what capitalism does to us on the inside; in the inner sphere of life, to our hearts and minds, almost to our karmic sphere. I think those questions have never been more pertinent, especially in this historical moment when it is inarguably clear that capitalism in its current extreme form is not only immoral, but technically flawed.”

Dominic’s a 33-year-old TV sound programmer. He was on his way to catch a bus when Montgomery’s words caught his eye. “I think they’re fantastic,” he says. “It’s nice to see things like this when you wander about. They have a different effect being out in the street as opposed to housed under a roof in a gallery. They’ll maybe resonate differently with many different people.”

Irene, a 27-year-old doctoral student who lives nearby in Oxford Square, says she doesn’t usually walk this way but is glad that, this time, she did. She likes the poems and hopes they stay up for a while. “I think they’re very much in tune with the area. Especially after the sort of discomfort we felt with the riots and everything this summer. You could tell there was something unexpressed somehow. And I think a lot of people can identify with a lot of the things that are written here. And it’s a good thing that they’re out in the streets, in an artistic and reasoned way, rather than being just another expression for discomfort. I’m happy they’re here.”

It’s this lack of discomfort that has always drawn Montgomery to poetry. “The quiet, reflective, melancholic state,” he says, “that trance-like reflection on the world is the pleasure of it.”

Montgomery’s poems hang near the vacant Old Street Magistrate’s Court, where, until recently, a group of Occupy London protesters had been squatting. “If you look at what Occupy are doing,” he says, “I think we’re finally seeing a positive international forum for positive change to the global financial system. That’s if we listen to them and don’t marginalize their voice.”

Emma is a 42-year-old Occupy camper and writer. She says she thinks it’s important to see artwork like Montgomery’s in the public realm. “Reclaiming public space is vital,” she says. “Art, music, poetry, performance, debate, conversation—these are the things that bring us together, that lead us out of our isolation, that allow us—the 99%—to connect, to share, and eventually, to mobilize. Every attempt to stimulate conversation regarding how we live now and how we could do it better is valuable.”

Emma says asking questions is just the beginning. “Questioning not just the artists and campers but one’s own self, the neighbors, the woman sat beside you on the bus or in the laundrette. Eventually, I hope that these messages will help humans to realize we’re all on the same side and that we can change our world for the better if we act together.”

Montgomery has been given permission to keep his Old Street poems up through the end of his gallery exhibit on Feb. 25. His recycled sunlight poem will eventually move to the site of the decommissioned Tempelhof Airport in Berlin, where it will spend another night, beaming its shared light through the same soft sky.