“The water came so fast.” That’s what you always hear, but I never understood what it meant until I watched the East River climb the walls of my apartment building. It’s not fast like a crashing wave or a bursting dam. You’re not dry and then wet. It’s not sudden so much as it’s suddenly lake-like where it had never been that way before. The transformation is so fundamental that you think it’d need days, or at least hours, but it doesn’t. In just minutes, there’s water where there was ground, and then water where there was wall, and then water at the windows and still more water. Water floating cars and billboard-size construction fences, swirling and cold and strong where you walk your dog, where you eat breakfast, where you work. The water’s real speed is its power to remake the familiar as hostile, uninhabitable, or even lethal regardless of planning, preparation, and every other effort. Its real speed is its inevitability.

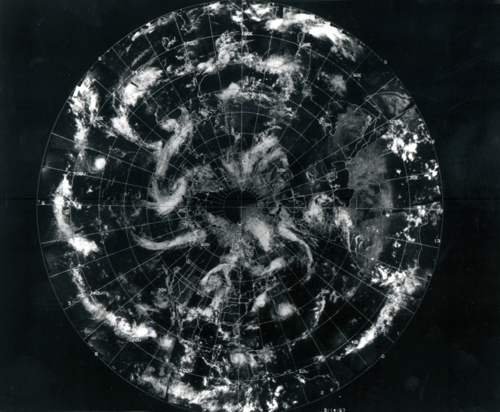

Eight days before Hurricane Sandy made landfall five miles south of Atlantic City, NJ, I started following it. Over the course of a week, I watched it grow from a low-pressure area known as 99L to Tropical Depression 18 to a full-fledged hurricane with high-speed winds spread across more than 1,100 miles.

I watched it move up the coast and inch along my computer screen and steadily increase the odds that it would make a damaging hit on New York City. I read about it at websites like Weather Underground and AccuWeather. I checked the updates as they came in from the National Weather Service. Words like “unprecedented” and “Frankenstorm” started appearing in the staid prose of meteorology. Days before Sandy hit, it was already “historic,” and I was completely obsessed, which meant a trip to the library.

According to Kristine C. Harper’s Weather by the Numbers: The Genesis of Modern Meteorology, the science of weather forecasting was born on Jan. 9, 1946, at a little after 10:30 a.m. in a conference room in Washington, DC. The head of the U.S. Weather Bureau and a handful of military meteorologists were meeting with Vladimir Zworykin and John von Neumann, two of the most celebrated inventors of the era.

Zworykin, an engineer at RCA who pioneered television technologies, was convinced that he could use von Neumann’s planned digital computer to solve the complex equations involved in meteorological modeling. Up until that point, scientists had understood weather patterns and had enough information to make fairly accurate forecasts but lacked the computing power to calculate results fast enough. At best, they could determine yesterday’s weather today. Zworykin was convinced that von Neumann’s computer could change that. He was convinced that new technologies would allow them to glimpse tomorrow’s weather today, to look into the future and plan for it and prepare and even change what was about to happen.

During the Second World War, the Allied forces used fire to cook fog and frost off runways so airplanes could land more easily. By the mid-1940s, American farmers were looking into cloud seeding with silver iodide, basically the same method used successfully around the world to this day.

On the Saturday before Sandy arrived in New York, I started to stock up: water, bread, peanut butter, dried fruit, nuts, ramen noodles, mac and cheese, cured sausage, crackers, beer, whiskey, seltzer water. On Sunday, I prepped. I brought up the stuff I had stored in the basement. I bought batteries and dog food and puppy pads just in case I couldn’t take Buster and Wolfi out to pee. On Monday, I walked around the neighborhood. I went down to the river. I took pictures. I checked and rechecked the forecast and watched graphics of the storm slowly bringing this wave-shaped icon closer. I drank beer. I worried. I waited with millions of others for something terrible to happen.

The U.S. Weather Bureau immediately saw the potential of Zworykin and von Neumann’s proposal, but few outside of the field believed that forecasting the weather was worth all the time and money it’d take to develop a reliable system. Controlling the weather, however, had obvious benefits that appealed to military leaders, policy makers, and others who were ready and willing to fund expensive research. And so before von Neumann’s machine was finished, and before Zworykin could make it work, scientists interested in getting funding for their meteorological research were packaging weather forecasting with weather modification. The immediate step after building a computer to predict the weather became controlling the weather for strategic purposes.

There were precedents for this line of thought. In the 1930s, British scientists began experiments to break up clouds with salt particles. During the Second World War, the Allied forces used fire to cook fog and frost off runways so that airplanes could land more easily. By the mid-1940s, American farmers were looking into cloud seeding with silver iodide, basically the same method used successfully around the world to this day.

The pioneers and backers of meteorology foresaw something far grander, though. Typhoons, droughts, and other violent weather events might become a weapon, or maybe a thing of the past. Disastrous storms, they believed, would soon be a relic of a less advanced era. One scientist even told a New York Times reporter that “the new discovery of atomic energy might provide a means of diverting, by its explosive force, a hurricane before it could strike a populated place.”

As Sandy drew closer to the East Coast, almost everyone brought up Irene, the hurricane that hit 14 months earlier. Despite a menacing forecast, mandatory evacuations, and a full-scale shutdown of the transit system, that storm merely swelled New York’s waterways and inconvenienced a lot of people. They weren’t quick to forget the seemingly unwarranted hype, though. Not fast to forgive the mayor who cried wolf. Of course, Irene did real damage elsewhere. In the Catskills and the Adirondacks and the Green Mountains, heavy rains overwhelmed streams and rivers and the water hit 100-year flood levels. You can still see sediment marks 15 feet high in places. Plenty of bridges are gone, plenty of homes too. In all, 56 people died. But few of us remember the storms that miss us. That’s a meteorological maxim.

Sure, yes, prediction allows for a certain level of preparation. It can save lives and infrastructure, but it couldn’t have stopped the storm.

Seven years ago, my friend Aaron Naparstek wrote an article for the New York Press about the city’s hurricane preparedness. It doesn’t mention anything about nuking deadly storms, but it talks a lot about planning for them and recounts some of the city’s biggest weather disasters. As I waited for Sandy to strike, I reread it, which was a terrible idea. First, he brings up the Long Island Express of 1938, the fastest-moving hurricane ever recorded, which destroyed some 57,000 homes. And then, there’s the storm in 1821 that pushed water levels at the Bowery up 13 feet in an hour, flooding the tip of Manhattan all the way to Canal Street. Most haunting is the story of Hog Island or, as he put it, “New York City’s version of Atlantis,” a small, sandy spit of land off the Rockaway peninsula that was a vacation destination until a medium-sized hurricane erased it from the map in 1893. When a college field trip uncovered some of it remains a century later, it took the class’s professor, a “forensic hurricanologist” based in New York City, nearly two years to identify what he’d found.

As I watched the photos of rising waters and scanned the cascade of Weather Service updates and last-minute calls for evacuations, I wondered how different the whole experience would have been without the forecast. What would we have done without all the information that Zworykin and von Neumann spawned since Hog Island disappeared? Sure, yes, prediction allows for a certain level of preparation. It can save lives and infrastructure, but it couldn’t have stopped the storm. I’d known all about Sandy for a week, but it was still coming, churning, pushing down on the ocean, displacing a sea’s worth of water. I always knew my obsessing wouldn’t change a thing, but still I obsessed. I checked and tweeted and blogged and took pictures as the water came up and the wind howled, not because I needed to know new things to prepare, but because I needed to know more than I did. To take part in this thing that was so powerful. To acquire knowledge about the storm as a way of gaining control of it. That’s how it’s supposed to work, right? That if I understand something and know it’s coming, I can do something about it? Or at least someone can?

Let’s be clear: Weather manipulation is real. You can read about it in the journal Nature, and you can sign up online for a license to do it in Texas. Tens of millions of acres of agricultural land in the United States benefit from cloud seeding every year. In China, the Beijing Weather Modification Office employs more than 37,000 people. A few of their self-reported accomplishments include a 12.5 percent increase in rainfall in 2004, snow on New Year’s Day in 1997, and a storm-free 2008 Olympic Games. Weather has also been used in combat: During the Vietnam War, the U.S. seeded clouds above the Ho Chi Minh trail, increasing rainfall by nearly one-third and ushering in the passage of a United Nations ban on “hostile use of environmental modification techniques.”

These efforts have also been turned to stopping hurricanes. Lots and lots of very smart people have done some serious research, though none of it has amounted to much. The problem, ultimately, is that hurricanes are very big and very powerful. The real issue with dropping a nuclear bomb on a hurricane, for example, isn’t the environmental consequence, but the bomb’s relative strength. It’s nowhere near enough—a ping-pong ball hurled at an elephant. Still, scientists, charmed by the same logic that helped make Zworykin and von Neumann’s research a reality, have tried. In the mid-1960s, the U.S. invested millions in Project Stormfury, which aimed to seed hurricanes and thereby weaken their momentum. In the 1990s, amateur hurricane-fighting proposals suggested carving out massive icebergs from the Arctic and towing them to the U.S. coast, to cool the water in front of a storm and slow its rotation. In 2008, scientists experimented with the idea that smoke injected into the lower levels of a cyclone might disrupt its movement, and most recently, in 2009, Bill Gates and his foundation sought five patents that essentially amounted to pumping very cold water from the bottom of the ocean to the surface, in another attempt to lower the ocean temperature and slow storm winds. All of those ideas failed.

Weather forecasts are this little piece of the future. They’re fate printed each day in the back of the newspaper and tickered across the bottom of the TV. Isn’t it immediately obvious why we want to alter what’s coming? Isn’t it also the most absurd thing you’ve ever heard?

I moved from the couch to a chair by the window. The East River had started to pool in the intersection below my apartment. The view was just like it always is, but the roads and sidewalks were replaced by glistening water that smelled like salt from the ocean and oil from furnaces in basements and cars parked on the flooded streets and even from decades ago when Greenpoint housed refineries. For all of my days of reading and preparing and vivid imagining, it was different from what I’d expected. The water was higher, sure. And smellier, definitely, but the scene was calmer. In the build-up, I’d thought the storm would arrive with a wild crush, with wind and driving rain. Sights and sounds that’d send me running. Something out of Twister, maybe, where a cow comes flying through the air. What came was almost the opposite. Quiet and powerful and slow and dark. One of those nearly inaudible pipe organ rumbles, those low notes that don’t make a sound but shake the church for divine effect.

There are a lot of very immediate reasons to disrupt a hurricane—death, destruction, billions of dollars in disaster recovery—but I think there’s another one that’s more primordial, and it’s connected to our tangled history of predicting the weather and trying to change it: Weather forecasts are this little piece of the future. They’re fate printed each day in the back of the newspaper and tickered across the bottom of the TV. Isn’t it immediately obvious why we want to alter what’s coming? Isn’t it also the most absurd thing you’ve ever heard?

Forecasting is this brain-achingly impressive scientific achievement— actually predicting what’s going to happen with a near-term accuracy of around 90 percent—and also, simultaneously, a monument to our impotence. Sure, we can plan and cope and nudge clouds to rain for the sake of war and farming, but the huge weather events—the life-changing ones, the ones that really matter, the one that was outside of my apartment a few weeks ago destroying homes and killing people—those are coming no matter what.

I got off easy. Even by the standards of my street, I was lucky. My family and friends are safe. My home is still here. All across the region, less fortunate people are still digging out, struggling, cleaning, and looking toward a better future, because that’s what we do. All of us are already looking forward, figuring out how to prepare and prevent damage from the next one. Just days after the storm there was talk of levees and storm barriers and giant balloons to inflate inside tunnels. All those things might be coming. Another storm certainly is. We know that much. And when we know it’s really coming—when we can watch it move on the screen, when there’s a forecast, a name, tweets—by then it’ll be too late to do much of anything except get out of the way before the water comes. That’s as true today as it was a hundred years ago, which doesn’t seem like it’s what people mean when they say, “The water came so fast,” but I’m pretty sure it is.