Within hours of landing in Piter, as St. Petersburg is affectionately called by its residents, I am seated in the former apartment of Elena Shvarts, the Russian poet who died in March 2010, with her dog, a spoiled and adorable Japanese Chin named Haiku, panting in my lap. It is late August 2011.

Although I never met Shvarts, and had not even read her work until after her death, Kirill Kozyryov, her closest friend in the last years of her life, is cooking me a dinner of fried tomatoes and eggs. He met Lena, as he calls her, years ago when they were neighbors and now lives permanently in the space she once inhabited with the dog she called master of the house. Addled from the long trip, I ask him only a few questions but soon find he will continue to talk on a subject for minutes, even if I interrupt, even if he pauses and seems perhaps to be finished.

In response to my scattered interrogation, he tells me that Lena was religious in the way of “the people,” that she was a good cook and a good friend, that she collected miniature figurines, and that she viewed the fall of the Soviet Union as a tragedy. I write it all down. I have traveled to Russia to apprentice myself to the dead poet: to learn, through Shvarts’s life and work, how to become a poet myself—which doors to shut, whether to get married, attend graduate school, convert to Catholicism, read the late Romantics, none of the above. “She was an imperialist,” he says and laughs. I write that down, too.

Before I leave, he tells me about the fire that destroyed this apartment in 2004: how Lena had just returned from a trip to Europe or America, and was in the tub, jetlagged but awake at around two or three in the morning, when something—a faulty wire? a smoldering cigarette?—sparked a fire in her bedroom. By the time the acrid smell of the smoke reached her and she called the police, it was too late to save much. The flames consumed the $10,000 in prize money Shvarts had recently received for her poetry, in addition to her possessions, her books, her late mother’s furniture.

As a young woman, Shvarts was reckless, wild, and sexy. She matched each poem, exacted from solitude, with a bottle of vodka split among friends. She was not alone in her drunkenness, but once drunk she distinguished herself from the others through outrageous behavior. As she recounts in one of three pithy memoirs, True Events From My Life (2008), she gashed open a friend’s forehead by breaking a bottle of wine over it. This was the worst injury she inflicted on anyone during what she called the “tempestuous period of her life,” although she was also arrested for attacking a man on the street who leered at her and a girlfriend. She could also be self-destructive: Shvarts recounts two separate occasions on which she nearly jumped out of a window. But this was the self she wanted people like me to find, the self she constructed, an accumulation of events built up like scaffolding to support her idea of herself. I wanted more.

For the next four days, I do not speak with anyone but for a short conversation with the young couple from whom I am renting a room. Jetlagged and anonymous in my friendlessness, I sleep until two then wander the city until sunset at 10. I begin to make a mental map of the streets around Shvarts’s apartment, then a physical one. I photograph the local churches, the canals, the dumps, and the pigeons, each time asking, Had she done this, too? Had she also stopped at this street at 4:07pm in a light rain? Walking by her apartment each day, I look searchingly into her shut window as if it were an eye or a mouth. Click. Each click more meaningful. Click click. The accretion of facts, I think. Click click click. No, not facts; the accretion of the details that will give me her, Lena, Lenochka, the person who boasted of writing her poetry in the bathtub, smoked, and lived with her mother for her whole adult life. I needed proof one could be both a poet and a person, a serious writer and a woman wearing perfume.

Before I heard of Elena Shvarts, I had decided, with childish stubbornness, that I would write my undergraduate thesis on a Russian woman poet. Russia had fascinated me since I studied European history in high school; Russian was the mysterious, beautiful language it seemed I would never master; poetry was the literary form that continued to confound me, the girl who read Middlemarch in fifth grade; feminism had found me when, as an eight-year-old, I realized my grandmother would compliment my outfit then turn to my 10-year-old brother for conversation. So when my thesis advisor, an accomplished Slavic scholar, suggested Shvarts—a woman whose poetry was visceral and difficult and barely translated into English—I latched onto her. The college chose to fund a three-week-long research trip to Russia, and I was determined to find the details that would enable me to write the feminist thesis I wanted to write, a thesis about the daily injustices facing a woman poet in the aggressively masculine world of the Soviet literary underground.

Shortly after I began to familiarize myself with Shvarts’s dense, mystical verse, I realized how ill-equipped I was to understand it, much less to translate and analyze it. Shvarts’s imaginative world, from her baroque diction to the literary allusions culled from her eccentric and diverse curriculum as an autodidact, was entirely alien to me. Take, for instance, her most ambitious, most representative work: a cycle of mixed lyric and narrative poems entitled The Works and Days of Lavinia, Nun of the Order of the Circumcision of the Heart (1984), which constitutes a spiritual Bildungsroman tracing the ecumenical quest of Lavinia, a present-day nun and poet, for mystical enlightenment and salvation. Through the persona of Lavinia, Shvarts grapples with the major themes that surface throughout her work: the mind/body division, religious faith, the painful solitude of the artist, and the complexities of female identity. Lavinia’s world is still mysterious to me, but since her quest—that of the poet simultaneously seeking the contradictory aims of belonging and transcendence—seemed not so different from mine, I decided to focus my energy on that text, that persona, that other, fictive self.

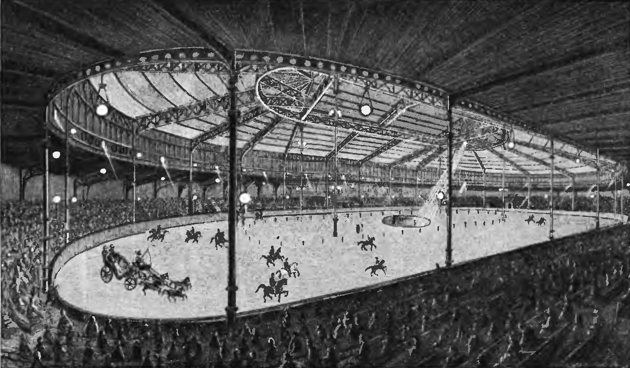

Confined spaces are central to The Works and Days of Lavinia. The cycle’s first poem is entitled “Hippodrome,” the ancient Greek word for “racetrack.” Within the hippodrome’s ovoid structure, there can be no progress or forward movement, only perpetual circling within. Until 1985, Shvarts and her small circle of artist friends met illegally for readings and seminars, behind drawn shades, in their cramped one- to two-roomed apartments. (Each day in St. Petersburg, I walk up and down the same streets, always, always thinking of Shvarts.) What’s more, the hippodrome’s self-contained nature, shape, and inward focus—crowds observe the race from inward-facing benches—correspond to the structure of the convent in which Lavinia resides, in turn correspond to the claustrophobic world of the literary underground in which Shvarts existed, in turn correspond to the structure of the mind. My neurons travel the same triangulated pathway each day: Shvarts—Lavinia—Self. No progress. No forward movement.

After the fifth day of outwardly aimless walking, I set my alarm for 9 a.m., eat breakfast, get dressed like a person who has somewhere to be, and set out for the Anna Akhmatova Museum. The museum, situated in the small communal apartment Shvarts once shared with relatives and strangers, serves as a literary center in the city. I tell an administrator I want to speak with people who knew Elena Shvarts. She frowns at me. Undergraduates get little respect in Russia, so I say it is for my dissertation at Harvard. “I only want to ask them a few questions,” I half-plead. She relents with a frown, and promptly begins making telephone calls on my behalf. “She’s a young girl. She doesn’t know the city. She doesn’t speak Russian well.”

The poet known as Boris Constrictor invites me to his home, where his wife serves us tea and chocolates. Flies swarm the fruit on the table. To all of my eight questions he repeats the same answer, “Everything’s already written down.”

After hanging up the phone for the last time, she looks at me and says, “These people were her friends. You can’t just go talk to them like she meant nothing to them. You need to know about her life. You need to read her poetry.”

She then proceeds to show me Shvarts’s Wikipedia page.

In the week after my visit to the Akhmatova Museum, I meet with six of Shvarts’s friends and peers. No one knows quite what to do with me.

I meet the poet Sergei Stratanovskii at a fluorescent-lit chain store called Teaspoon. He insists on buying me tea and a pastry layered with slightly yellowed cream. When we sit down with our napkins and plastic trays, I take out my notebook and start asking questions I hope are grammatically correct. Eventually, he tells me Shvarts carried herself like a “capricious child,” but that Russia had seen only a few poets as visionary as her. “She was a genius,” he says. “And she knew it.” There is some bitterness in his voice. It occurs to me he might wish a young American student would write about his work. After tea, he sets me up on the library website at a nearby Internet café. I know how to search the catalog at home, so I leave before the allotted time is up. I’m not sure whether he planned on coming back to get me.

I meet the critic/writer/translator Valerii Shubinksii at the upscale chain Coffee House in a mall-like complex near the Alexander Nevsky monastery. We sit at a faux-mahogany table and order espresso. After exchanging pleasantries, he answers my questions as the scholar he is, so I probe further, for the personal, until he describes Shvarts’s first public reading: she wore a long gypsy-style skirt as she read, theatrically as an actor, from Works and Days of Lavinia. He is, I note with a star in my notebook, not the first to point out her beauty and her small frame.

I meet the historian Evgenii Gollerbakh at one of the Teaspoons off of Nevskii Prospekt. We both take our coffee black. He answers my questions with such directness and brevity that I am unsure what to say next. He had been very close to Shvarts at the end of her life, and at the moment he says the word “emptiness” I fear he will break down in tears. At the end of our talk we sit in silence for five minutes as if at a wake. Before we stand up to shake hands and part ways, he gives me 10 pages of type-written text that turns out to be an intimate elegy-in-prose he wrote for himself after her death.

The poet known as Boris Constrictor invites me to his home, where his wife serves us tea and chocolates. Flies swarm the fruit on the table. To all of my eight questions he repeats the same answer, “Everything’s already written down.” Before I leave, he gives me two of his books and asks me to donate them to my college library. “It is a dream of mine to have my books in every library.” I keep my promise to do so.

Yes, I have had friends like her, I think, and there is a reason we are not friends anymore.

I meet Tatyana Martynova, the mother of Shvarts’s close friend, the German-Russian writer Olga Martynova, in her neat, silent apartment located in a large, Soviet-era complex of identical concrete buildings on the outer edges of the city. She serves me tea and chocolate (eat, eat!) while I sit on the pull-out sofa on which the displaced Shvarts slept after the apartment fire in 2004. “None of her girlfriends would take her in,” she tells me. “So I did.” Before I leave, she sits me down at her computer to read an essay her daughter Olga wrote about the weeks she spent with Shvarts on a fellowship in Rome. Tatyana hovers behind me for the 20 minutes it takes me to read the whole piece. I am comforted by her account of their friendship: not all poets, I think, green and ignorant as I am, need be loners.

Shortly after, I meet the poet and professor Arkadii Dragomoshchenko at the center of another industrial housing complex. Books line the walls, crowd the floor space in tall stacks, cover the living room furniture. After clearing a chair of books and motioning for me to sit, Arkadii serves me instant coffee. In response to my question about Shvarts’s identity as a specifically female poet, he observes that, although she liked to refer to herself as an androgyne, “her sex appeal was so overwhelming when she read, that everyone simply gaped. No one even knew what exactly she said.”

When I tell him that I am interested in writing about the body in her work, he refers me to Deleuze. I scribble a phonetic interpretation of the name in my notebook. I’ve never heard of the philosopher, and though I won’t end up using Deleuze, Arkadii’s words about Shvarts’s sexual allure will end up in the final draft of my thesis as an example of “inadvertent gendered criticism.” Perhaps.

Half-way through my three-week trip, I’ve replaced walking with reading: her poetry, her memoirs, her interviews. Her poems I break down and sort into columns of nouns, adjectives, verbs; then further into active/passive, feminine/masculine, archaic/contemporary, etc. Her memoirs I parse for connections to poetry and oblique references to gender that will support the thesis I’ve set out to write. Her interviews I read and re-read with the hope I’ll find something new on the page. I am so immersed in the life of her mind that I like to imagine the boundary between “her” and “I” has begun to blur. She is my mentor and role model held, safely, at a distance from which I can continue to idealize her extremes: her genius, beauty, and smallness.

By this time my work has found its rhythm, so I am starting to feel quite smug and self-satisfied. Though Shvarts still stands in my mind on a pedestal hewn with the word POET—not PERSON, not WOMAN, not SOMEONE I COULD HAVE MET AT A COCKTAIL PARTY—I’m generally pleased with my progress, pinpointing moments of what could be interpreted as feminist frustration and locating it, transmuted, in her poetry.

That is my state of mind one rainy day, when, sitting sidewise on a boxy, uncomfortable armchair and reading her memoirs, it occurs to me that I know people like Lena. And: I do not like them. She was, I think, with slow disbelief, while idly fingering the broad green leaf of a dusty houseplant, a spoiled, privileged child. Yes, wickedly smart, wildly precocious, doted on by teachers. But also capricious, prone to sudden outbursts, egotistical, and self-assured to the point of arrogance. What’s more, the interviews have left me with the distinct impression that she had not been not skilled at retaining friends.

Yes, I have had friends like her, I think, and there is a reason we are not friends anymore.

I put down the book and pace the living room, speaking aloud to myself.

Could I be wrong? Yes but I know I am right. How do you know? I don’t know, I can’t know, and yet—You’re self-assured to the point of arrogance? Yes, but—Why? Well, I was precocious, always doted on by teachers. Oh were you? Yes, though not—What made you that way? I was privileged, perhaps slightly spoiled. Yet you’re good-tempered? Well— Well? Well, no. I’m irritable, overly sensitive, not swift enough to apologize. Almost there. I am not so different than her. And? She was human.

Early one sunless, chilly afternoon, I head to the Volkovskoye Memorial Cemetery, where Lena is buried. The cemetery is located at the last station of a half-finished metro line in one of those industrial no-man’s lands that surround Russian cities, and probably comprises the entirety of some Siberian ones. There is no map of the sprawling cemetery. I do not search for her stone. Instead I walk into the small onion-domed church, pay five rubles to light a candle before a dimly lit icon of a female saint, and introduce myself in a kind of prayer.

I’m sorry, I say. Then: Ignore me. I don’t know what I’m doing. I don’t speak Russian well. But your writing has the most incredible energy. It won’t disappear.

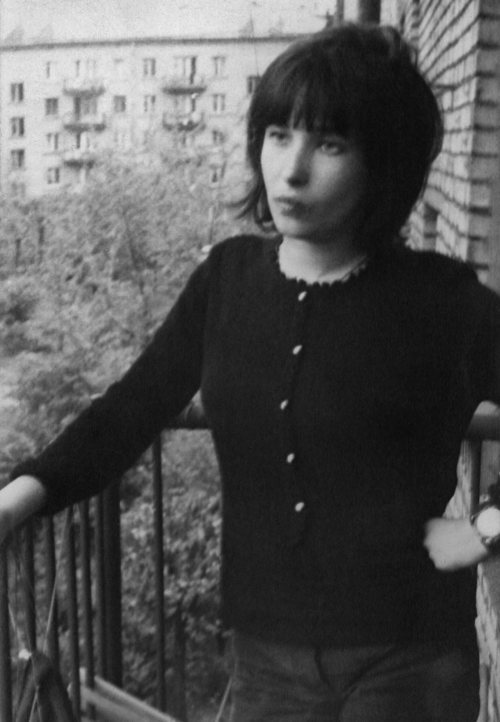

Shvarts was notoriously and obstinately camera-shy so photographs of the poet are few and far between. However, on the first night I arrived Shvarts’s friend Kirill showed me a brief video, which he managed to shoot from afar without attracting her attention, two or three years before her death, at 62.

Exterior shot. Winter landscape. Day. Shvarts walks across a flat, ice-white field followed by her little dog. Her own small figure is so heavily bundled that it appears almost childlike, although she is nearly 60. Without warning, she interrupts her stride to turn away from the wind and fall backwards into snow. For a long minute, she remains supine, letting her dog clamber onto her stomach. When she sits up, she is smiling.