The Writing of Art

Protesters are clashing in the street over paintings. What is it, whether in art or literature, that makes one thing better than another?

“A story has two things,” a writing teacher once told me. “The plot—thing one—and the emotional situation the reader cares about—thing two.”

At the time, we were discussing Andrea Barrett’s short story “The Littoral Zone,” which is about two biologists having an affair on a remote research station, and subsequently dismantling their marriages and professions to be together. It’s also—thing two—about making a decision you can’t take back, and the cinder of regret forever smoking in a new relationship. Another way to say it: there’s text and subtext. There’s the plot and the emotional arc.

As a painter, I couldn’t help but reflect on lessons I was hearing in writing classrooms when I returned home to my studio. Walking through museums with my dad when I was young, there were always certain paintings I gravitated toward; my father, also a painter, had taken me to see paintings since I was old enough to carry the coats to the coat check. Two paintings might be nearly identical in composition—say, both landscapes—but there was one that was, to put it bluntly, better.

Why did I love Winslow Homer’s paintings—

so much more than Albert Bierstadt’s?

Why were Rembrandt’s portraits magnetic, but the other Dutch portraits collected on the opposing wall not? Why did I love John Singer Sargent and Swedish painter Anders Zorn, but could ignore a whole gallery of Pre-Raphaelites?

Recently, at dinner, I asked my dad what he thought made a successful painting. It’s a question that the art world has rightfully resisted from answering. Art depends on uprooting definitions of good or bad; painting should be about working through questions, not answering them. My dad was quiet for some time before saying, “A really expensive frame. Gold frame, even better.”

Ha. But I see what he’s saying—the difference between a good and bad portrait is an easy distinction, but hard to define. “I know it because I feel it here,” he later said, pointing to his heart. One of my mentors, Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum, told me in his characteristically enigmatic way something almost identical. We were sitting in his studio south of Oslo, looking through a Leonardo da Vinci book. “I can feel it,” he said of a certain da Vinci painting. “Here,” he said, pointing specifically to his own right foot.

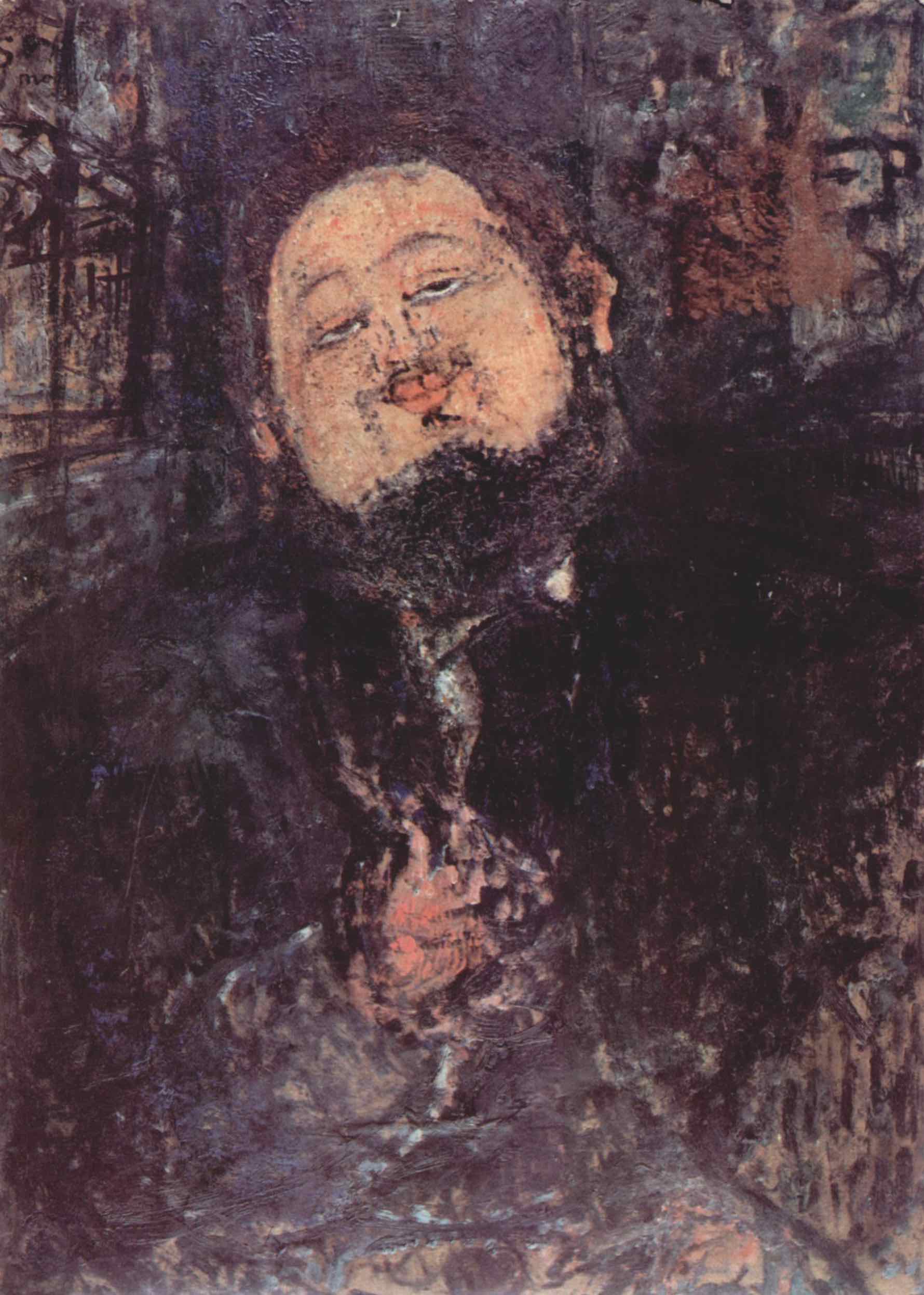

But when I heard the two-parts analysis from my writing teacher, it all finally snapped into shape: paintings[[1]] are also about two things.

First, there’s the content of the painting—call that the plot. Thing one. What’s happening in the painting. Rembrandt is wearing a funny hat and looking at you:

A wave erupts over a rock in Maine:

Ivan the Terrible kills his son:

A woman dances:

Plot. That’s easy. Everything in Representational painting (also called Figurative painting, Realism, or Naturalism) must have a plot, must have a describable event, even if it’s stopped motion. Ishmael goes on a whale hunt; the sun sets.

Part two: A painting must have, like a story or novel, an emotional arc.

If I were to draw a one-to-one comparison between fiction writing and (figurative) painting, the emotional question would seem to be the intentions of the painting: why the painter rendered what he or she did, what emotional question is he or she answering?

It would be the equivalent of Andrea Barrett rendering through linked scenes that smoking cinder of regret, answering the question of what might remain when you dismantle a life for lust. You would ask what Winslow Homer intended to say when he painted a scene of waves. Rembrandt when he painted himself in different hats. Robert Henri when he painted snow-filled city streets:

Cecilia Beaux when she painted her brother-in-law with his cat:

Lucian Freud when he painted naked people sprawled on dirty mattresses, or Van Gogh when he painted fields of poppies:

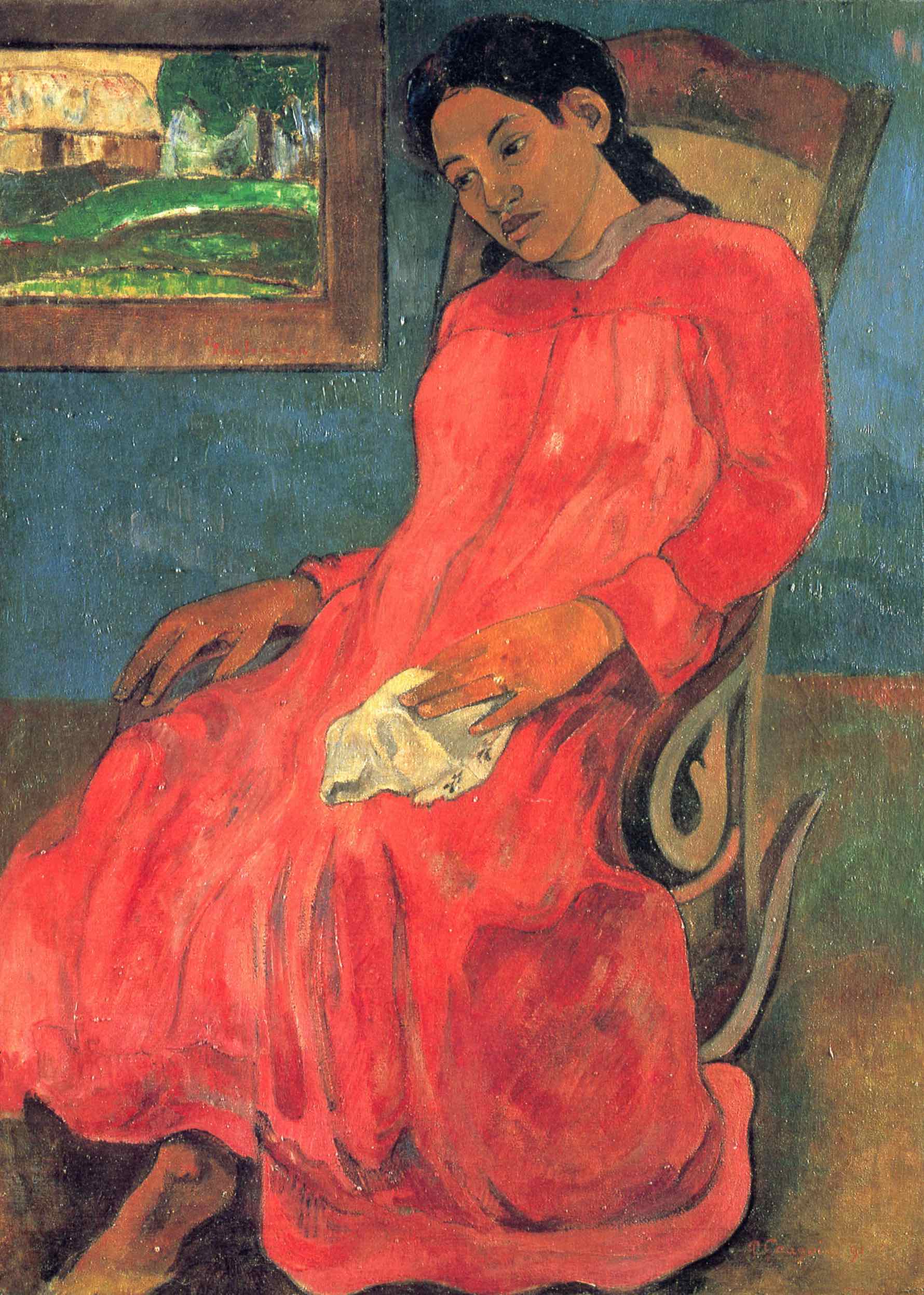

Gauguin when he painted a Tahitian woman:

But the intentions behind a painter’s composition (the plot) are often mundane or undocumented. Landscape painter Albert Bierstadt worked on commission by big railroad companies or westward explorers. John Singer Sargent painted famous socialites. Van Gogh painted what was on his table (sunflowers) or behind the asylum (fields of lavender).

There are also more institutional reasons: For a long time, western oil painting was done in the service of the Church. Full stop. Then, in Velazquez’s case, for instance, in the service of royalty (King Philip IV in his case). Then in the service of rich families who could afford to let their food rot on the table. Then in the service of one’s own aesthetic: I guarantee that contour-obsessed Winslow Homer simply loved how waves feathered up the side of the rocky Maine coastline.

That’s all to say in the centuries before 1900, painters didn’t have to think much about why they painted what they painted—they were either told what to paint, needed to pay rent, or did it in service of Heaven. To ask Titian why he painted religious themes is like asking Roger Federer why he plays tennis, instead of enjoying the sight of his forehand.

The emotional response (part two) is in the handling of paint.[[2]]

You see Lucian Freud’s 1995 painting “Benefits Supervisor Sleeping,” for instance, and your mind reads the light coming into your eyes as naked woman on a couch. But you’re also clearly, undeniably, looking at a nest of brushstrokes, which your mind works at untangling. You think, look at how this painter arranged oily rock and plant material on cotton canvas to mimic flesh. You relish the trickery of it, the duality of it being so evidently heavy paint but so much like a roll of skin. The phenomenon of two things happening at once collapses time. I think this is what makes people addicted to good painting. It feels good to see two things simultaneously—just like a really good denouement in fiction. A character closing a door or missing a train or not saying something she should say can be a depth charge of multiple meanings. The life-altering episode of premature ejaculation in Ian McEwan’s On Chesil Beach is as compactly potent as one of Wayne Thiebaud’s paint-laden cupcakes.

I think people love Rembrandt paintings because they glow. They glow because of the age-ambered oil mediums stuck in the gullies of paint applied with Rembrandt’s characteristically heavy hand to look, from a few steps away, exactly like a reflective bead of light resting on the skin, cast from a nearby candle or window. You notice the brushstrokes while noticing how much those brushstrokes mimic flesh.

I like Old Masters paintings more than tightly rendered new ones produced in Academies to mimic Old Masters simply because of the way the paint has cracked over the centuries. The way those hairline cracks vein over royal faces. Heavy brushwork could be attractive for other reasons: there’s the one-of-kind, inimitableness of it. There’s the joy of witnessing expression rather than exactitude. And there’s the trick that brushy paintings, even from long ago, are always new because the painter’s action—those few seconds it takes for a brush to drag over the canvas—is captured. We see the archeology of the material. But I like to stand close enough to Singer Sargent’s freakishly succinct and precise brushwork—was he an alien robot sent from the future?—to relish the plurality of the paint, not to witness the path his hand took.

Look at these two works by 19th-century American George Inness. Plain, simple landscape—to take genre and color out of the equation. Paintings that would hang together, and that seem as common to museum walls as ever. The earlier one, “The Lackawanna Valley” (1855), isn’t an exciting painting:

Inness has removed the brushwork in favor of recording the landscape as it was. Compare that to this one, a later work, “Sunset on the Passaic” (1891), smothered in burnt orange paint:

We see the paint as light. There are two things happening with that paint. It tells a story. It acts as paint itself.

Artists know that handling of paint is the emotional heart. Entire movements have been launched by that fact.

Impressionism…

Expressionism…

Pointillism…

Fauvism…

A Pointillist has preserved the dotted strokes; an Impressionist the globs that imitate atmosphere. Nobody cares about lily pads, they only care about the way Monet put paint on the canvas to render those lily pads, free of form and distorted by atmosphere.

Some painters in the 19th century take the application of paint as the emotional core of their work so seriously that they switch styles entirely through the years. Look at these two Dennis Miller Bunker paintings:

Abstract Expressionists took the Impressionists’ sensibilities and distilled them into a sort of blinding moonshine. Not only did Pollock and his gang uncover the virtues of paint and expression without form, they uncovered the truth about what makes transcendental representational painting—the way you reveal the making of a painting; the bolder and more lasting the method of application of paint onto the canvas, the greater the emotional response. What happens in a Jackson Pollock painting? Nothing. Lose the plot.

Trying to convey emotion in composition (plot) and not brushwork (emotional question) is misguided. Author Benjamin Percy has a quote that applies to this: “A-list movies are always about a B-list plot; B-list movies are always about an A-list plot.” Nineteenth-century Pre-Raphaelites attempted to engage the viewer’s emotional response in composition, which made the work infamously sentimental instead of emotionally resonant. One of my favorite figure painters today told me that there are still paintings that are taboo. “A deer drinking from a lake at sunset,” he said. “You can’t make that painting.” Sentimental. He’s right: viewers don’t care about the story of a good painting’s composition.

Trying to convey emotion in composition (plot) and not brushwork (emotional question) is misguided.

In Freud’s work, we see naked, sitting people. In Rembrandt’s and Nerdrum’s, potato-faced northern Europeans staring at you. And those painters figured out that, really, we don’t need any more from composition to make an emotional painting. We want a man looking at us, deadpan. We want brushwork. But the brushwork should be integral to the painting, not tacked on (smears or drips for the sake of smears or drips). The work should be approached from the inside out, just like the advice of another writing teacher: “Write from the inside of a narrative.” Or another, “Make the work its best self.”

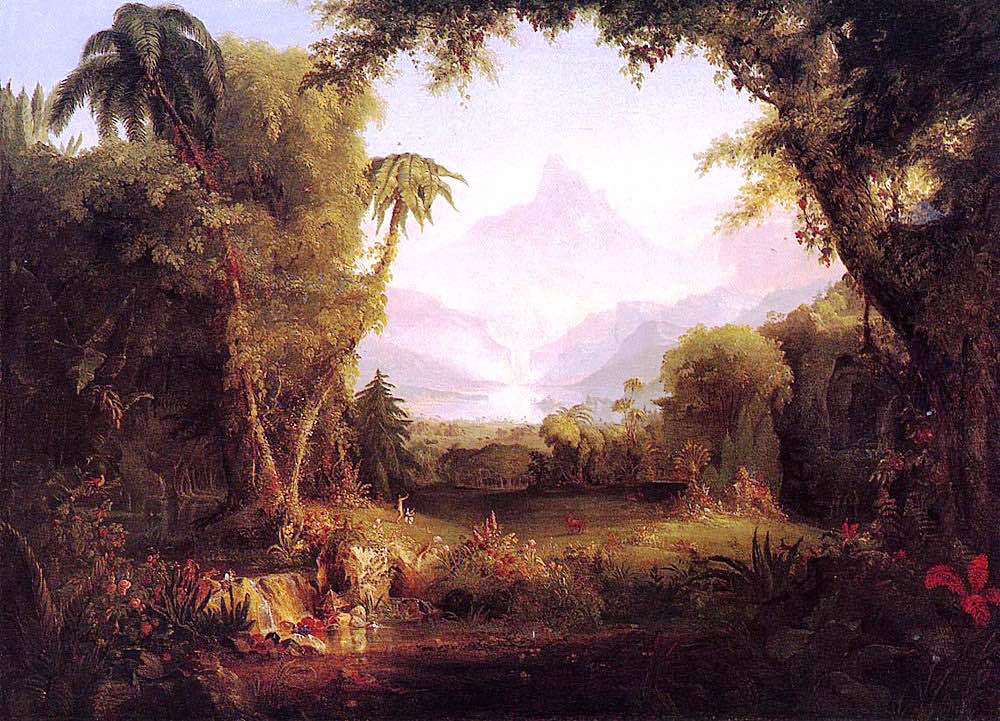

For as long as painting has been around, artists have proposed formulas that make a good work. There’s a rule about framing a landscape with foreground, which makes nearly identical compositions regardless of subject:

Or that objects in a still life should create a triangle:

Or that portraits are best at a three-quarters-turned face:

Or lowering the lights in the background to amp contrast:

But too many successful painters break rules. The only thing that remains is evidence of the artists’ hands by the paint, and the artists’ mind working out brushstrokes that are self-evident and accurate of the thing that paint is representing.

I’ve found this thing-one-and-two lesson (plot in composition, emotion in brushwork) useful as I’ve since walked through galleries and museum. It’s a signpost, not a rule, though, and there are a thousand ways to argue it. It might be Van Gogh’s colors that people love. It might be the flirtations and secret gestures in Renoir’s work that people like. It might be Monet’s horizon-less compositions of lily pads.

But for me, when I don’t love a painting, it is probably lacking thing one or thing two of the fiction lesson. And when I do love a painting, the brushwork and composition are both strong. Though sometimes there’s no way to explain why a painting is good. Sixteenth-century artist Pieter Bruegal and the more recent Andrew Wyeth are some of my favorite painters for no identifiable reasons. I just feel it, here, in my right foot.

[[1]]: None of the following applies when it comes to abstract or abstracted painting. I can’t comment on that tired proclamation of painting being dead, but I will say that figurative painting is, if not expired, certainly in hospice. Abstract painting, meanwhile, is doing cartwheels across the lawn outside. The few institutions and individuals still squeezing the I.V. bag for its last representational drops have insulated themselves behind the walls of Academies—Florence, St. Petersburg’s Repin, and the Imperial Academy of Arts—and the galleries in midtown Manhattan or downtown Naples, Florida. If representational painting is worth doing—debatable—we should plant the signposts that indicate what makes successful representational work. More, we have museums full of the stuff, but many have, I think, lost the vocabulary to describe why we like some but not others. In another essay, I would discuss why I think it’s important to keep representational painting around, which, if you’re in art school or subscribe to Art in America, you might think is something like watchmaking or churning your own butter. At any rate, from now on, for simplicity sake, when I refer to painting, I mean representational painting.

[[2]]: For some time I thought that the handling of paint was the equivalent of prose—the more expressive painter would be the more poetic writer. English painter Jenny Saville would be Anthony Doerr’s recent Pulitzer-winner All the Light We Cannot See, the prose of which is like a jewel-encrusted locomotive chugging ahead for 400 pages. Way out in the last quarter of the book: “I have been feeling very clearheaded lately and what I want to write about today is the sea. It contains so many colors. Silver at dawn, green at noon, dark blue in the evening. Sometimes it looks almost red. Or it will turn the color of old coins. Right now the shadows of clouds are dragging across it, and patches of sunlight are touching down everywhere. White strings of gulls drag over it like beads.”