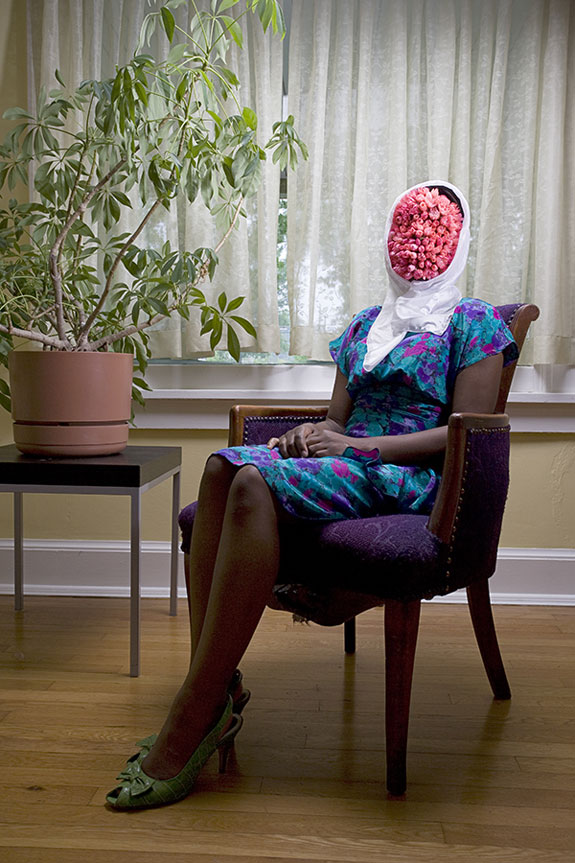

The women and (occasional) men in Alison Brady’s photographs look uncomfortable and provoke our discomfort—exactly what Brady’s going for in her collection “An Uncertain Nature,” currently at Massimo Audiello Gallery in New York (Jan. 8-Feb. 28, 2009). Unconscious emotions and repression come through in her rich-toned scenes of domestic torture, a reminder that the space between safety and dread is smaller than we think.

Born and raised in Cleveland, Alison Brady lives and works in New York City. She is currently represented by Massimo Audiello Gallery. Brady holds an MFA in Photography from The School of Visual Arts (NYC), has shown both nationally and internationally, and her work is featured in private and pubic collections such as the West Collection and Sir Elton John’s Collection. All images © Alison Brady, courtesy Massimo Audiello Gallery.

The shoot itself seems like a performance. How do you set up these shots?

There is an extensive amount of preparation involved in each piece, from the conceptualization to the finest details of set dressing and costuming; even grocery shopping. Looking at the images afterwards I can see them resembling documented performances, but all the particularities involved would probably make watching the process pretty boring.

These works, despite their occasional absurdity or surrealism, seem meticulously arranged. Where do you get inspiration for a particular image?

Some ideas come from my subconscious, or maybe my neuroses, others come from what I notice in day-to-day life. I came across an ad on the subway of a treatment for varicose veins and was struck by the idea of blue veins suddenly appearing on the body—something as intimately close and familiar as one’s legs becoming foreign seems especially resonant, even freighting. This gave me the idea for the image of the woman’s legs coming out from under a carpet. In this image the woman has small balloons stuffed inside her stockings that are intended not as a reference to anything specific but instead as an exploration of the realm between the familiar and the unknown. The unnerved feeling one gets when the familiar turns alien and frightening.

Do you use professional models, or do you have a preexisting relationship with your subjects?

Identity is often effaced in my work, with models representing ambiguity as much or more than anything concrete, so any preexisting relationship with the models is not necessary for the image. The work attempts to play on feelings of instability, and subjects are placed into awkward or bizarre set pieces and coerced into visually compelling poses. Using strangers would seem like an obvious choice, but I have found that it has no effect on the meaning of the image. However, none of the models are “professional.”

Why do you mostly photograph women?

You make work about what you know; being a female artist, my work comes from somewhere personal.

Do the scenes or images represent personal emotions or responses? Or are they more of a critique?

My images allude to the cryptic mental re-scrambling through which our traumatic events resurface, something like a peek into the subject’s psyche. Each staged tableaux intends to prod at obscure discomforts in the viewer—the idea of violation, of trauma, of those lucid moments whose unreality is escalated to a sort of super-reality.

Your face is covered in a sack in your self-portraits. Why shoot self-portraits in this way?

I’ve never seen that image as being a self-portrait. To be honest, the model canceled that day and I used myself out of necessity and from just wanting to create something. I actually don’t make it known that the image you’re referring to is me. I did end up using one of those shoots showing my face for the bio page, but it was more to comment on the use of humor in my work. I did use myself in one of the Spaghetti portraits, though.

The women in your work are literally tied, trapped, bundled, and rolled up in their anxiety and alienation—what is the next step here? How do we progress?

I envision the role of the artist as that of broadly posing questions, rather than providing answers. Answering one’s own questions, in my opinion, often makes for lousy art.