Excerpted from The Blind Photographer: 150 Extraordinary Photographs from Around the World, edited by Julian Rothenstein and Mel Gooding, published by Princeton Architectural Press, 2016.

Visions of the Real: The Desire and Will of the Blind Photographer

Mel Gooding

The eye, it is said, is the window to the soul. But what if blinds have been drawn across that window? In a darkened room, the mind thinks, the imagination constructs and shapes reality, and the spirit animates: Each does so in their characteristic and unpredictable forms, each with their necessary vigour. Thought and feeling are as one. For the blind person, all is in “the mind’s eye”: That is a faculty shared with the sighted when the room is in darkness, or the eyelids closed to the light. The blind Slovenian photographer Evgen Bavcar wrote: “Even a blind person has visual equipment, optical needs, as someone who is longing for light in a dark room. From this desire, I photograph.” To look at photographs taken by the blind is to recognise this desire as one shared by all: In this way, these photographs are a revelation of the world of light, a manifestation of a common longing, a triumph of creative imagination, creations of the mind’s eye rather than the brain’s.

In recent years, photography by blind photographers has become a worldwide phenomenon. This may surprise us. Photography created by those who cannot see may appear paradoxical at first (the very word photography, after all, comes from the Greek, “drawing by light”). But is it necessarily so? We are used to the idea that the loss of one faculty enhances the acuity of those that remain. Looking at the photography of the blind we encounter the paradox that it is sight itself that seems sharpened by blindness. Even the most severely blind person must have a vision of the world, created imaginatively with the help of the other senses, to answer to Bavcar’s “optical needs”, a sense of things in space.

In contrast, the camera itself has no “sense” of things, no “eye” (in spite of the common metaphor), no brain, and no creative mind; it is nothing more than a machine that catches the light of a given moment; it cannot create meaning. But, like everybody else, the blind live in the world of light whether they can “see” it or not: The mind’s eye imaginatively “pictures” the world, senses the relations between things, plucks meaning out of the flux of everyday experience. Memory is likewise a common faculty, however idiosyncratic its individual operations. The camera may thus be seen as a visual aid, so to speak, a technology by means of which the blind photographer may present to others something imagined in the mind visible in the common light. It makes things appear.

Since they cannot see what light refracts into the mind through the lenses of the eyes, or what the camera plate registers on its momentary exposure to the light, the blind must use other information to construct the picture of the world necessary for sustained communication. And of course, blind people (in most cases) are in constant communication with those who are “sighted”. Reality, in fact, is a marvellous collaborative construction: the shared, continuous construing of what we might call the contingency of the actual. What is occurring? What might it mean? This coherence −always necessarily provisional− that we call “the real” is created by the blind and sighted alike. In the light of this shared world, we might well ask: Why has it taken so long for photography to be recognised as a vital medium for this constructive exchange of understanding between the sighted and the blind? Looking at the photographs in this book, it seems such an obvious and inevitable facility of communication!

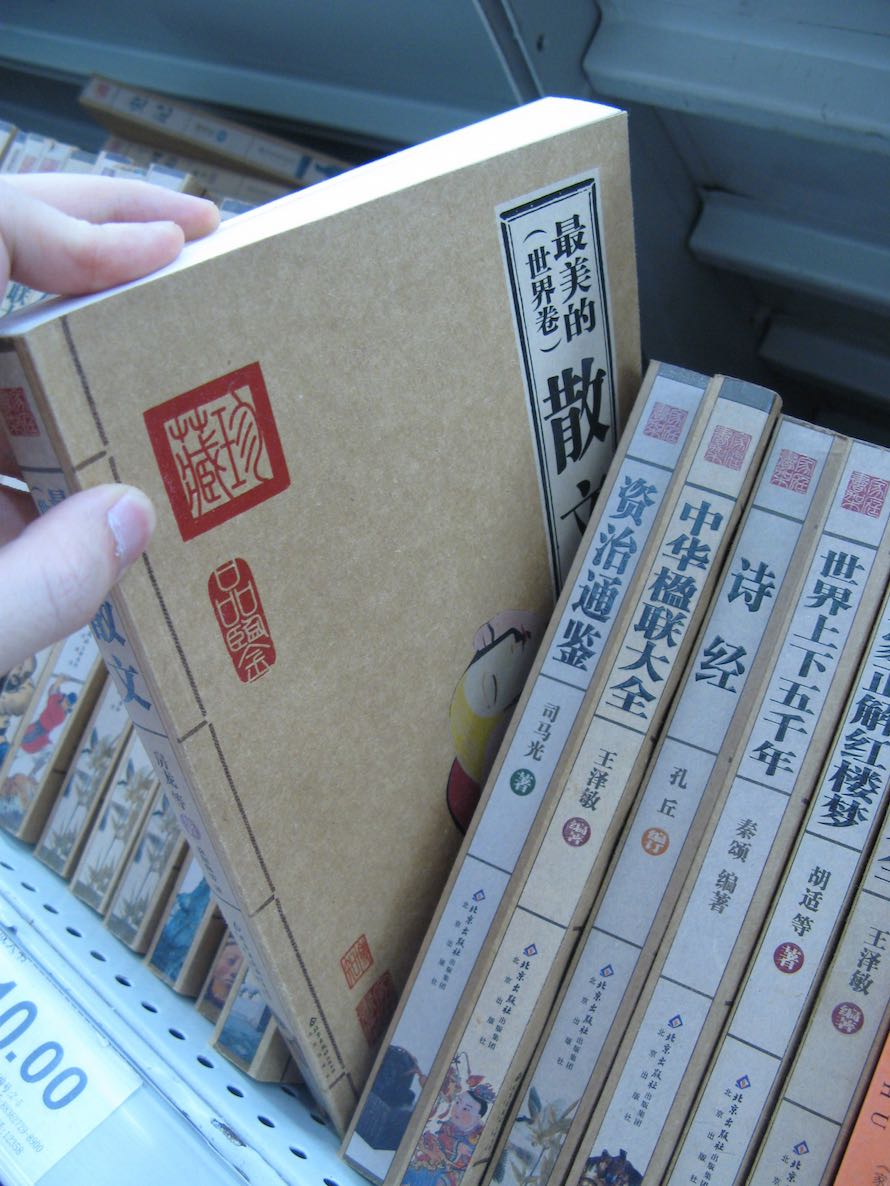

The Blind Photographer offers to a wider public than ever before the extraordinary vibrancy and diversity of the work of blind photographers. It showcases brilliant and moving images from Mexico, India, Europe and China. It discovers many aspects of that shared reality and of its diverse mediations, infinitely different in kind as they must be: In the absence of sight, they have been created out of the imaginative complex of touch, smell, taste and hearing, presenting themselves as images pure and simple to that very faculty of sight. Helen Keller taught us, of course, that even when there is more than one sense absent, a rich world of shared thought and feeling might be brought into being. The mind of such another, its mysterious operations shaped and tempered by feelings we cannot possibly divine, will often surprise us with its unpredictable projections and discoveries. Thus our own mind is expanded, our imagination enhanced.

The book is not a history of photography by blind practitioners. It is, rather, a thrilling presentation of the work made by such photographer-artists. It is an anthology: As the etymology of this word implies, it is a gathering of diverse flowers. It serves to remind us that there is indeed a great diversity in the condition of blindness: The experience of blindness is different for every blind person, just as sight is a function of personal history, experience, temperament, culture and social situation. Some are born blind; some have blindness thrust upon them. Of the latter, some have a residual visual perception of the world, however shadowy or vague; some have light or colour sensations; all have memories of the seen world. The work of blind photographers is as diverse in content and manner as that of their sighted peers.

All blind people must imagine the space they inhabit, and there is no living space devoid of objects. As with the sighted, the blind spend their days and nights negotiating these objects, near and far in their circumambient space, objects that necessarily possess sensible characters of colour, form and scale, qualities of hardness and softness, roughness and smoothness, etc. Among those objects are, of course, the myriad other creatures, human and otherwise, that share this living space. A photograph cannot by definition reproduce what we might call the sense of presence, the affective relation of objects to the living subject, though it may suggest it to the receiving imagination. The camera itself can do nothing more than register light in space and on the surfaces of objects; the space that the sighted share with the blind; the objects with which the blind and sighted alike continuously interact.

These relations with things in the familiar places in which we live create the very texture of our being: They are existential and not abstract, they shape our sense of a life, our life. It may be the case that the blind cannot see these things, but they can, as we see, photograph them with powerful affect; as with the sighted, these things are the very substance of their physical and experiential habitat! Modern psychology has established that our senses are not simply or absolutely separate and autonomous, but that thought, memory and feeling are inextricably linked within the complex of our daily experience of the world. No one sense, in other words, can function in isolation from the others. For all of us, the world is realised out of the interaction between them, and the absence of any one sense in no way changes the principle of this psychological complex of sense and sensibility. Into each encounter with the objects in the continuous space of the world, the blind, like the sighted, take their bodies with them; each with it’s distinct and complex sensorium, each with its concomitant mind and imagination. Every photograph is a record of such a sensational encounter: with people, buildings, walls, fruit, flowers, toys, the street, the kitchen, the living room, the bedroom, the beach, the pool, sunlight, darkness or shadow. Blind photographers take photographs because photographs are there to be taken.