Julie Heffernan’s paintings are guided by the pictures that visit her between sleep and waking. And like the pensive, cautionary nature-boys in her new paintings, Heffernan cobbles together tokens and symbols to create a natural world as beautiful as it is gentle.

Julie Heffernan was born in 1956 and received her MFA from Yale University. She has had numerous one-person exhibitions around the country and has shown internationally. She has received a Lila Acheson Wallace award, New York Foundation for the Arts award, a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Fulbright-Hayes Grant. She is the program head of the BFA in Studio at Montclair State University. Boy, O Boy is currently on view at PPOW Gallery through June 5, 2010. All images © copyright the artist, courtesy PPOW Gallery in New York City, all rights reserved.

How did you decide to use the male figure for the first time in these paintings?

Well, it started out to be a rant about how we have got to change our lives, our culture, our politics, our economy. We have to think of our art as our platform. The landscape and figures are dealing with needs to imagine different possibilities. One is the need to move out, the other is the image of remaking the world. Sprinkled into that were the male figures as a way to say, come on males, you guys are perpetrating a lot of shit. It was a negative view, but as I got deeper into the paintings, especially the figures, I realized they were negative in a way that wasn’t interesting to me. It was a screed as opposed to a revelation.

These paintings don’t seem chastising at all. How did you manage to soften the images?

I was bringing to bear all the imagery that was fed me. It started blunt and angry, and then I was slowly able to bring a world of wisdom to it. My son is leaving home—we’re redefining our world, we’re redefining our culture, and I’m redesigning my family as my son goes to college.

So is this about being instructive to your son or others in some way?

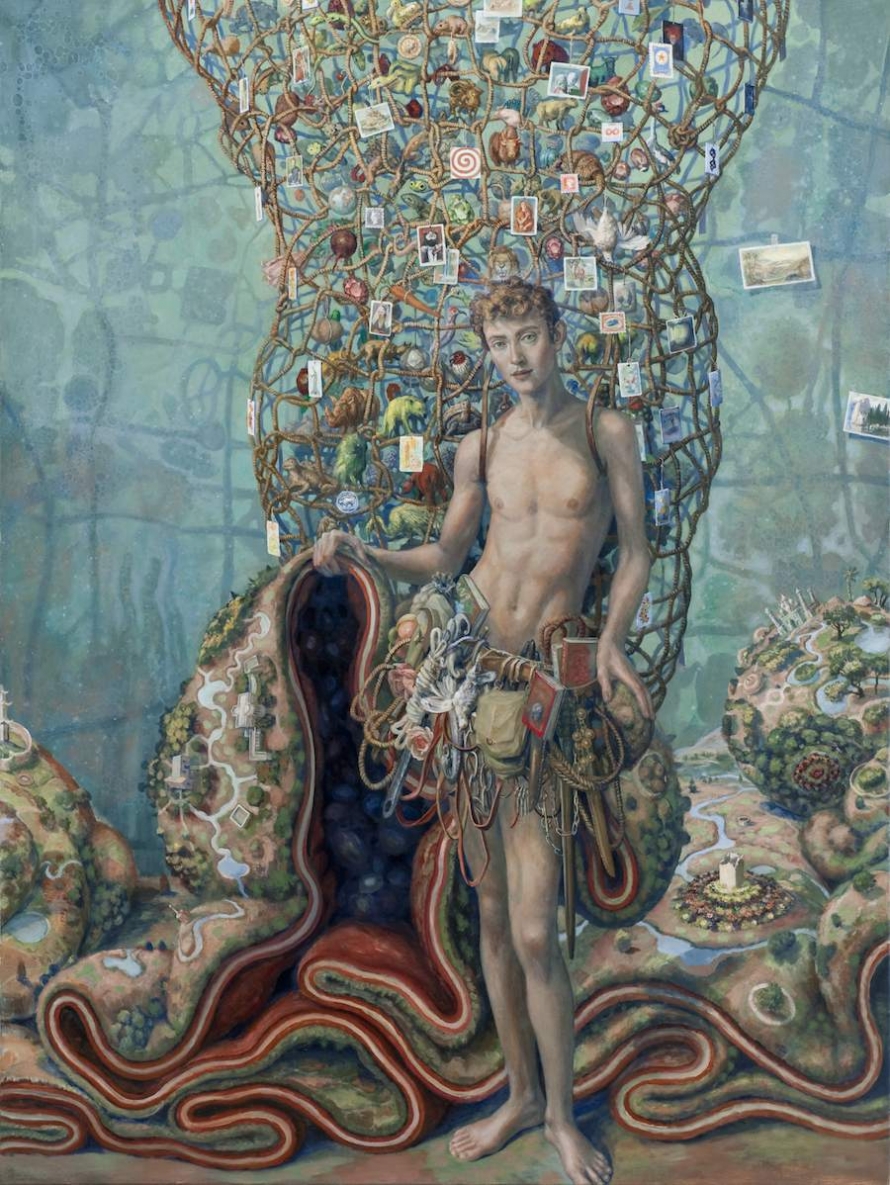

It’s tenderly proffered advice. He won’t listen, but I talk about it as providing a toolkit for him to go off into the world with.

Has the toolkit had any effect within your relationship?

I think so. My kids are two boys and my studio is in my house. They’ll come down, and there was an early point when the kid’s toolkit had grenades. My son Oliver looked kind of aslant at it. I thought, “Ooh, no, I don’t want him to be full of guns and grenades.” It was reading his face that made me realize what the painting was asking for. There was one time when he said, “Oh, I like that,” and I said, “Well, it’s kind of about you.” He had no idea. The boy in the painting sort of looks like him so it was very funny that he was so oblivious.

You talk about speaking to the world and about the world, but do the imagery, tokens, or symbols in your work have personal or psychological relevance?

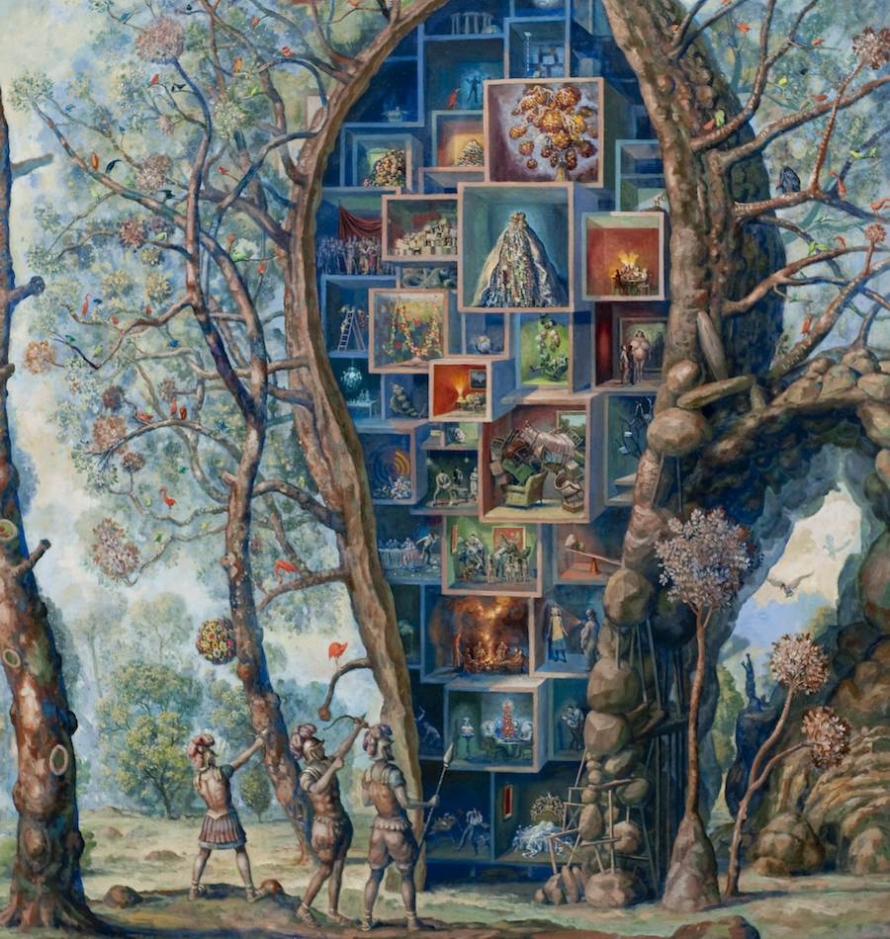

In the painting “Self Portrait Setting Up Camp,” the space itself is meaningful. The story needs to be told not only in the particulars of the subject matter but also in the form of the painting itself. The form of the painting is a spiral. It both whirls you out and wheels you back in. There’s a large space that is integrated by this spiral and within the spiral are all the particulars, the punctuation points. In the outer leg of the spiral is a stream of water, on the stream of water is a little raft made up of sawed-off logs that are in a circle shape. There’s a little fruit stand on it. All of those images brought together create the idea of offering, sacrifice, nurturance—nature in its plucked, offered-up form. The particulars augment each other.

Adjacent to the stream, I can see the mother with her children.

They’re between her legs as though they’re just birthed, and they’re also kind of playing as though they’ve been protected and they’re already on their way. I was thinking about who we need in this world. Paring down the kinds of people we need, I brought it down to: the healers, the dreamers, the buriers, the builders, the fishers, the storytellers.

I read somewhere that you get ideas and inspiration through a process called “image streaming.” How does that work?

It works differently as I develop, but when it started I had been through graduate school and this very intense Fulbright year in Berlin, really painting for 16 or 18 hours a day. Malcolm Gladwell talks about the 10,000 hours, and I think I was hitting my 10,000 hours or something. I started to notice that as I would relax and go into a fade-away state before sleep, I would be dreaming these images from nowhere that wouldn’t relate to anything I had seen in the day or was painting at the time; they would come to me like a movie. Francis Bacon talks about it, a lot of people do. I would just kind of watch this movie and think, “Oh my goodness this is so much more interesting than what I’ve been painting.”

Over the next few years, I changed everything I was doing stylistically so that I could see these images more clearly. That’s why I went toward what some people call the old master image, but what I think of as “Light and Shadow.” Over time the image streaming has given way to an inner sort of mind voice where I don’t necessarily see a particular independent image so clearly as I am being told by the inner voice what to do in the painting.

Your work seems very self-generated but it also reminds me of a lot of art in different mediums—sculpture, film, fashion, or literature. What are some influences outside of painting?

I move to the imagery that feeds me. I’m not so fed by popular imagery in the sense of billboards. I’m not fed by fashion. I’m very much fed by film.

What sort of films influence you?

The first one that comes to mind is Breaking the Waves by Lars von Trier, or Jane Campion’s The Piano. I love the intersection of the madman and the saint. I think of my characters as functioning a little bit in that way. In the case of the women with the animal skirts in my last show at PPOW, they’re the vessel for showing the predatory and the fruitful natures of humankind. She’s the sacrificial victim and also the person who transcends victim-hood. In The Piano, she embodied a female sexuality that was about polymorphous perversity or multiple sources of sensuality—visual tropes that bring to mind the metaphorical nature of sexuality as opposed to being focused on genitalia.

And this contradiction is happening in the “Boy, O Boy” work as well?

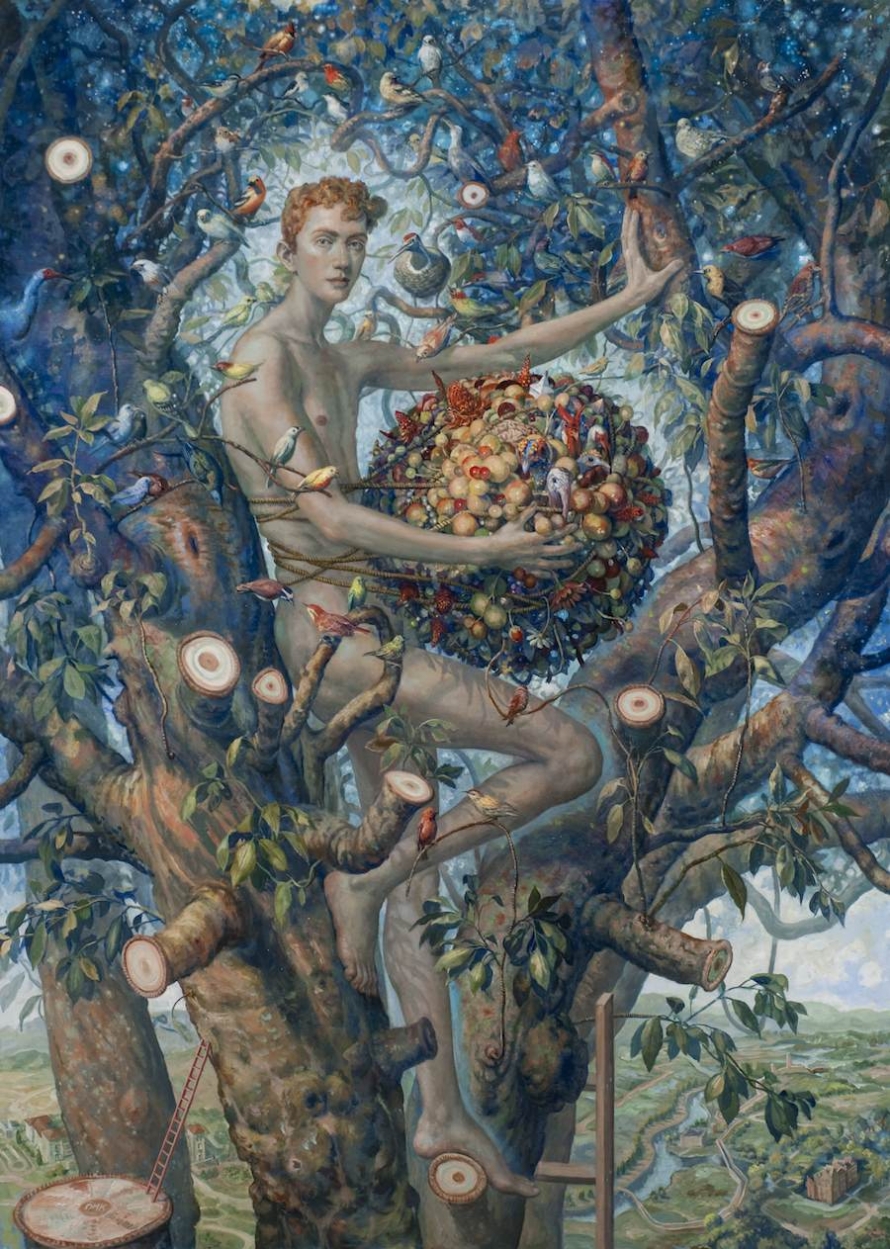

Very much! In the painting “Budding Boy,” the space next to him in the tree was empty for a long time. When he got the big ball of fruit and turkey heads and birds and he became kind of pregnant, it was like—“Oh, oh, oh, this is it! He’s fulfilled the Jungian imperative.” A friend came and saw that painting and was disturbed by the lopped-off branches, but I was thinking he was building his environment. This pregnant belly that is roped to him is a thing he’s built and created.