What becomes of resorts planned with big dreams—yachts, country clubs, roads paved and phone poles wired—that never materialize? Forty minutes from Palm Springs, photographer Marshall Sokoloff spent two years roaming the deserted zones of Salton City, tracking the desolation.

To coincide with with this gallery, one of Sokoloff’s images from this series is available as a limited-edition, signed and numbered print as part of Coudal Partners’ ongoing Swap Meat feature. Click here to find out more.

Photographer Marshall Sokoloff lives in Vancouver. He can be reached at tmn at marshallsokoloff dot com. See previous galleries of his work here at TMN. All images courtesy Marshall Sokoloff, all images copyright © Marshall Sokoloff, all rights reserved.

Statement by Marshall Sokoloff: My father had dreams. He was going to be a pilot. He was going to get a small plane and fly us to our dream family cottage on Martha’s Vineyard. My father could do anything. I believed that once.

But, as with David Sedaris’s father in “Our Perfect Summer”, these things are much more easily dreamed than acted upon.

My father’s dream was once mine too. These dreams help to sustain us—keep us moving forward.

And sometimes we actually achieve these dreams—we get that sunny place where the weather is always perfect. Or we build our ideal business that caters to those dreams of getting away from it all.

But these dreams live most of all in our minds—in our hearts and our memories. The actual place is practically secondary… the idea lives on even if the place does not.

In 2006 and 2007, my photography started to embrace a recurring theme of these dreams, those forgotten, lost and spoiled. Although I have photographed this theme throughout North America, the area around Salton Sea, CA has drawn my interest most.

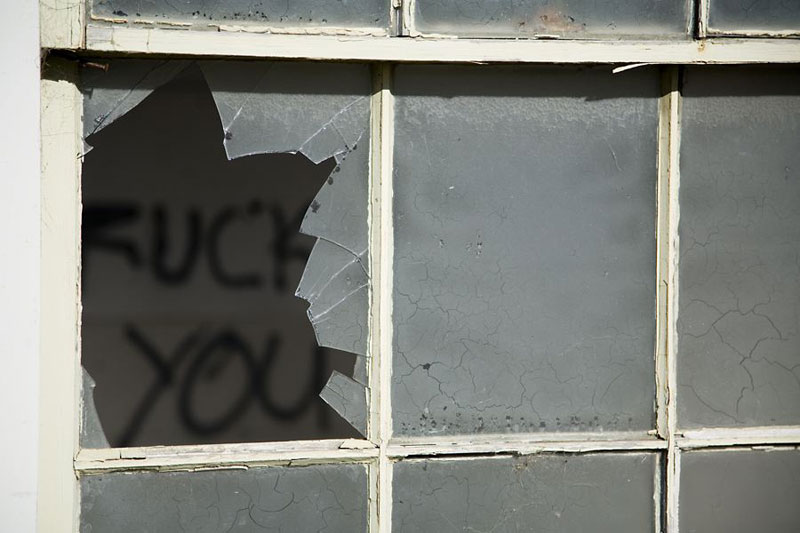

Envisioned in 1958 to be a grand resort town in the desert, Salton City represented the highest hopes for its residents. Time and man-made disaster have shattered those dreams.

There is beauty in these relics, examples of people realizing their desires. They are just ghosts now—again living only in their dreams.

We all have a place in our mind, a place we will go for rest and retreat, a place we dream about.

How did you first learn about the Salton Sea? How much time did you spend there?

I first became aware of the Salton Sea in the early ‘90s when I read an Outside Magazine article about the pollution in California’s Imperial Valley, in great part coming from the Mexican border boomtown of Mexicali. The article also talked about “Slab City,” an ersatz town a couple miles away from the Salton Sea, inhabited by squatters, living—“boondocking”—mostly in rundown RVs on the site of a long-since-decommissioned military facility.

At the time, I had no real interest in photography, but the idea of the area always stuck with me.

The photographs I shot at the Salton represent three separate visits, all early morning. It’s worth noting that on two of those visits the temperatures were over 100 degrees, and one of them was 115 degrees at six a.m. Strolling along the Salton’s shores in those conditions was a special kind of hell.

In all, I was in the vicinity of the Salton—Joshua Tree, Palm Springs, Borrego Springs, El Centro, Niland—for about three weeks.

Wasn’t the area once a successful resort? Does anyone live there now?

I’m not sure how you might define successful. It was certainly planned to be successful. If you look at Salton City, CA on Google maps, start first on map view, and after looking at the incredible quantities of streets built, switch to hybrid view to see the real story.

The developers actually built all of those roads, and wired them all for electricity. For the most part they still exist—the asphalt is cracked and overgrown, but still very much there. These roads lead to desert lots for houses that don’t exist. Here and there you see people presumably squatting on some of these lots, living out of an ancient camper trailer or an old school bus.

There are a number of abandoned homes there, but not as many as you might imagine. There may once have been more, but there’s not much evidence of that. The reality appears to be that there really never were that many—at least not when you consider the infrastructure that was put in place.

There are a number of abandoned RV resorts, all of them right on the shore, and they are the saddest and most forlorn of all. Such high hopes they had for their water vacations—plots facing out over the water, community halls, laundromats, and boat launches. All that remains is the shells of some of the buildings, the concrete RV pads, and the remnants of their AC hook-ups.

Some people do live there now. There are perhaps 200 homes in Salton City, some are spread about across the vast landscape, others are in a couple RV parks that are well looked after. Everybody now seems to live there in spite of the Salton Sea, not because of it. The Salton Sea itself can best be described as a cesspool, with no attraction for any human—hyper-salty, extremely polluted (despite what the deniers say), an acrid and unappealing water mass ringed with the bones of fish and fowl apparently unable to survive the Sea’s effects. Never in my multiple visits in the last two years did I ever see a boat on that water, or even see a local appearing to enjoy its shores.

Oddly, there is also a bit of a housing boom going on now, too. There are a number of newly built houses there, and land seems to be changing hands. One can presume that the land must be cheap, and there are things about the area that are attractive—particularly for people that like space. It’s only about 40 minutes from Palm Springs, and the stunning Anza-Borrego State Park is just to the west. The areas to the north and south are fertile farmland, and the local farm workers need inexpensive housing choices.

On the Eastern shore of the Salton Sea, across from Salton City, is a far more modest town named Bombay Beach. In many ways it is more successful than Salton City in that it is more densely inhabited, albeit a much smaller town. It doesn’t seem to have sprung from as grandiose a plan as Salton City, and still holds many abandoned and nearly abandoned homes. What is distinctive about Bombay Beach is that it had a fairly large RV park on its shore, one that appears to have been caught off-guard by the rise of the Salton Sea after a couple of tropical storms. As the sea’s levels rose, it flooded the dwellings on the shoreline and the RV park. The homes that were there are long gone, but some of the remnants of the RVs remain. Those long-abandoned trailers have been continuously flooded with the rise and fall of the sea levels, and the high salinity of the water has eaten away at what’s left of the trailers, to very dramatic effect. Since the water levels started to rise unpredictably, a dike has been built to protect the rest of the town, and what’s left of the shoreline has been given over to the whims of the Salton Sea.

There are quite a few web sites out there chronicling the history of the place, but nothing that I have seen so far that really describes how the place feels.

You’ve concentrated on decay and erosion before—what draws you personally to sites like these? Are you always alone in these types of settings?

I think that I’m primarily drawn to these places for their untold stories. I feel moved by their histories, which are largely un-chronicled, but can be imagined by seeing the patina of their surfaces.

Many consider my area of focus to be primarily textural abstracts, and while this is one interest, it’s all part of a larger theme of showing the overlooked. I’m particularly moved by the places and processes that manufacture items that we take for granted.

To this end, I’m currently shooting a lot around agricultural and forestry themes.

For the most part, I shoot alone. Occasionally I might stop while traveling [to stay] with a friend, but having someone around invariably makes me feel rushed, and often results in uninteresting shots. Also, for me the action of taking pictures has a very zen-like quality to it—it’s a meditative state when it’s really working, and that happens best for me when I’m on my own. There are instances when having someone else around is a comfort, though—some of my locations are dangerous-feeling places. And now that meth labs have sprung up so much in desolate places, it’s a real concern.

When we had drinks last year, you talked a lot about the air of the place, the spirit that seemed to be like dust on everything. Do you remember that?

The dust was a metaphor, actually. The thing is, that the area feels very untouched by modern society. There are many, many people there that are living on the margins, people who have for whatever reason—monetary, psychological, or individualistic—elected to live in such a forlorn place. It would be easy to say that it’s just a place for societal dropouts, but that would put it in the same league as other desert hideouts like Joshua Tree or Ridgecrest—which it is really nothing like. The Salton Sea is profoundly sad in a way that’s very hard to explain: The Salton Sea is broken dreams.

How did being there affect you?

I think that in spite of what I say above, it was an uplifting and positive experience. It has helped me to get in touch with some of what motivates me as an artist, and has helped me to sort out some reflections on my own childhood.

It has also helped me to formalize some of the photographic themes and statements I want to pursue in the near future.

You’re a fairly transient person, frequently traveling. When you visit someplace you’ve already been, are you aware of what it was like when you were there before?

I am very aware. The curse of photographers is that rarely will you get identical conditions two visits in a row. Many potential shots that I skip with plans to return to later disappear in the interim. Interesting buildings get torn down or fixed up; things get rearranged. Light quality is very hard to predict—I rarely shoot anytime except early morning, but many sites to which I return for that morning light disappoint. Waiting for great light can be a frustrating thing. There are so many different factors that have to align in order for great shots to happen. As a natural-light photographer, it’s easy to see the attraction in studio photography.

I travel back roads a lot, and really follow my nose poking around. Prior to most trips I research the hell out of these areas, looking for possibilities—investigating the primary industries, past and present, looking into economic and environmental factors that may have played on the landscape. Often, I will be convinced that there will be a great shot in a certain place, only to come up emptyhanded and then stumble upon a spectacular composition as I’m driving home.

I’ve actually resisted temptations to revisit places of cherished memories from my childhood. I’ve done this after discovering an interesting phenomenon. After revisiting places from my past, the more recent trip’s memories actually start to replace the memories that I had from my childhood. And since some of those memories are so precious to me, I don’t want to do anything to compromise them. They have really become mere dreams to me—a place and time that exists only in my mind. For this reason, I have never been back to Yosemite as an adult. Hence the title: “Dreamland.”

What are you shooting next?

I always have my gear wherever I’m going, so I never have to regret missing a shot. I could point to many of my best-liked shots that were taken when I was on my way to someplace else, to shoot something else.

So, “next” is whatever comes to me on the way to somewhere else. I’m keeping my eyes open.