Los Angeles

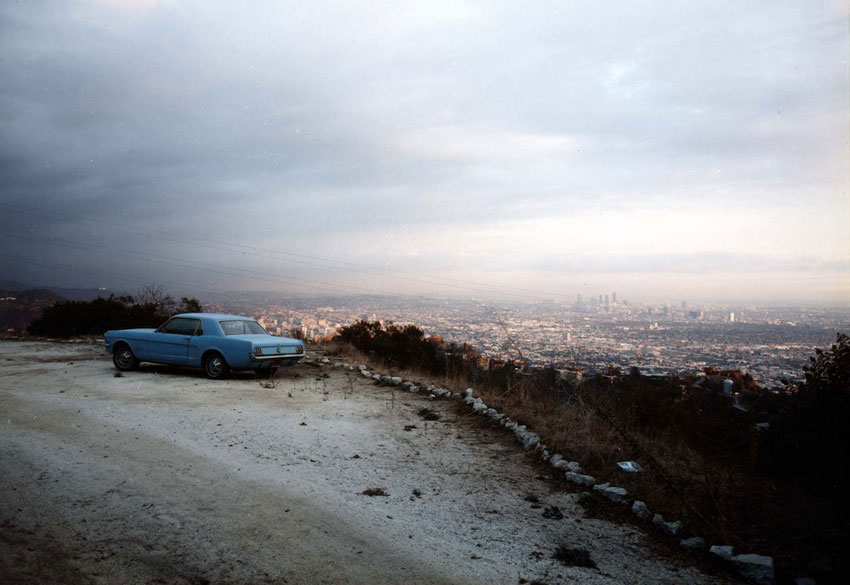

These photos tell the story of Adam Bartos’s move to L.A. in the 1970s, when he arrived expecting Hollywood glitz and glamour and instead discovered the serene and all-American images in this series.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

Your photographs seem patiently and meticulously planned. How do you set up your shots?

The pictures are all “found,” so the only thing I set up is the camera.

How did you decide what to photograph?

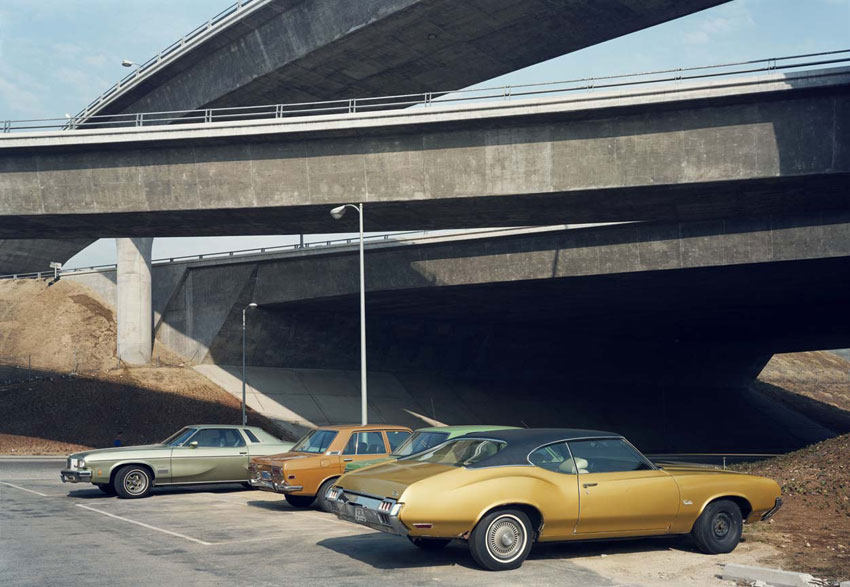

In these L.A. pictures, I was drawn to certain light and colors, spaces, vernacular architecture, and automobiles that, to me, were characteristic of the place in a way that resonated with how I was feeling and the photographic agenda I had. These acted as visual cues. I didn’t want to photograph anything that was particularly noteworthy. But sometimes the elements in a street scene would be arranged in a way that appeared to demarcate a border or a little area that is set aside. Maybe the quality I was responding to could be described as “in-between.” Continue reading ↓

Bartos's show Los Angeles is currently on view at Yossi Milo through January 20. All images appear courtesy of Yossi Milo, and are copyright © Adam Bartos; all rights reserved.

Interview continued

What’s your relationship to the actual sites where you’ve photographed?

I moved to Los Angeles from New York in late 1978 (when I took these photos). I rented an apartment in Ocean Park, a comfortable area between Santa Monica and Venice Beach. Most of my time was spent driving around looking for pictures and trying to acclimate myself. I wasn’t very familiar with the landscape.

What’s unique or exceptional about the spaces you’ve shot in L.A.?

I think they are all fairly typical places except for the two interiors taken in my friend Tom Consilvio’s kitchen and dining room. He was a very exacting person, a photographer and black-and-white printer who worked with Garry Winogrand. I was very fortunate to spend time with Garry as well, driving around, going to the Farmer’s Market, and so on. These friendships were sustaining, as L.A. was overwhelming to a newcomer.

When many people think of L.A., they think of movie stars and freeways. Your photos depict a much more familiar existence. How did you find this more relatable and ordinary Los Angeles?

For obvious reasons, the film industry dominates the received view of L.A. If you live there and aren’t in the film business, it’s not a big part of daily life.

Like everyone who doesn’t live in L.A., I had all sorts of images of it in my mind put there by film and television. In fact, the mythic L.A. was probably closer to me than the real one, and definitely affected my choice of subject matter. I was predisposed to find glamour in the undramatic; what you might see through the car window in a drive-by shot.

How many L.A.’s are there? Is the L.A. in your photos the “real” Los Angeles?

L.A. is a very diverse and huge place. Real estate values and climate permit things to change relatively slowly, and maintain some visual continuity with the past. There are countless real L.A.’s and my photographs document the appearance of a few places that don’t pretend to be something they are not (although, if they did, that would be just as real).

Parenthetically, the authentic Los Angeles encompasses the “New York Streets” sets that can be found on the Universal, Warner Bros., and Paramount lots. These New York streets, when dressed properly, might easily feel more authentically New York than real New York, especially now that our (New York) streets are lined by the very same shop-fronts you find in Pasadena, Beverly Hills, Brentwood, and Paris, France, etc. It’s all real and even authentic, but the distinctions become less meaningful.

You’ve photographed commodities or technologies that are the source of great pride, either national or individual—I’m thinking in particular of your photographs in Kosmos. What are the objects of cultural or national pride in these photographs of Los Angeles?

The Beach Boys’ songs had tremendous allure for me as a child growing up on the East Coast and I was always interested in cars. When I stayed in Ocean Park, I wasn’t far from the epicenter of board culture in Venice. As I mentioned, film noir and 70’s color films also influenced how I saw L.A. In the show, I suppose the objects of pride would be the Mustang and the Camaro.

I was struck by all the cars in these pictures. Why have so many cars and roads ended up in your L.A. photographs?

I was working on the streets with a large-format camera, so that was the landscape. I was engaged with the tradition of street photography, and influenced by all sorts of models, especially 19th-century landscape photography like Watkins and O’Sullivan up to Stephen Shore and William Eggleston’s work, which I admired tremendously.

This work was done in the 1970s, have you shown it before now?

These photographs have never been exhibited until this year. Several years ago I started to look through a lot of my old 5 x 7 work and discovered that I had made things I really liked now, from the period in L.A. I brought a few to my publisher, Pascal Dangin, and we incorporated them into what became the book, Boulevard, from which the shows sprang.

How do you feel about them now?

It’s wonderful to see color pictures that were made almost 30 years ago newly printed and looking as good or better than they ever could. The old cars may add an air of nostalgia, but that’s not at all the point.