Past Time

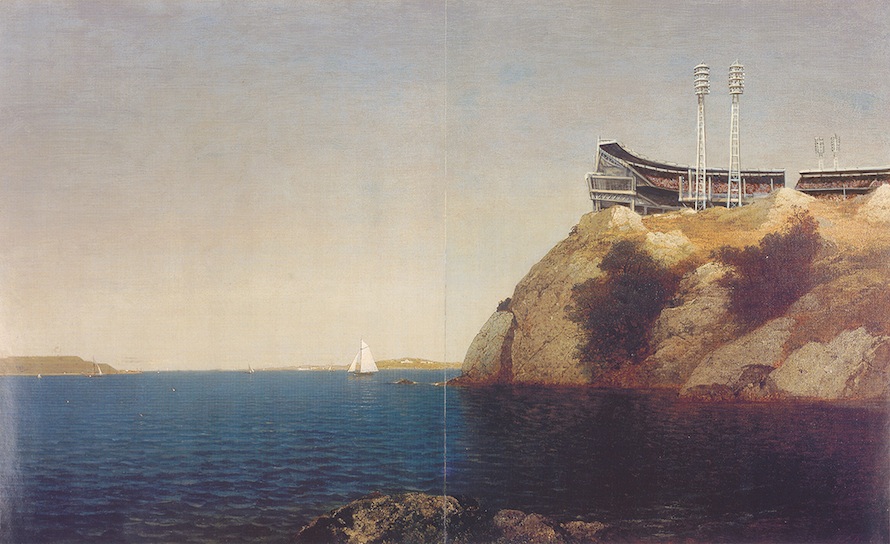

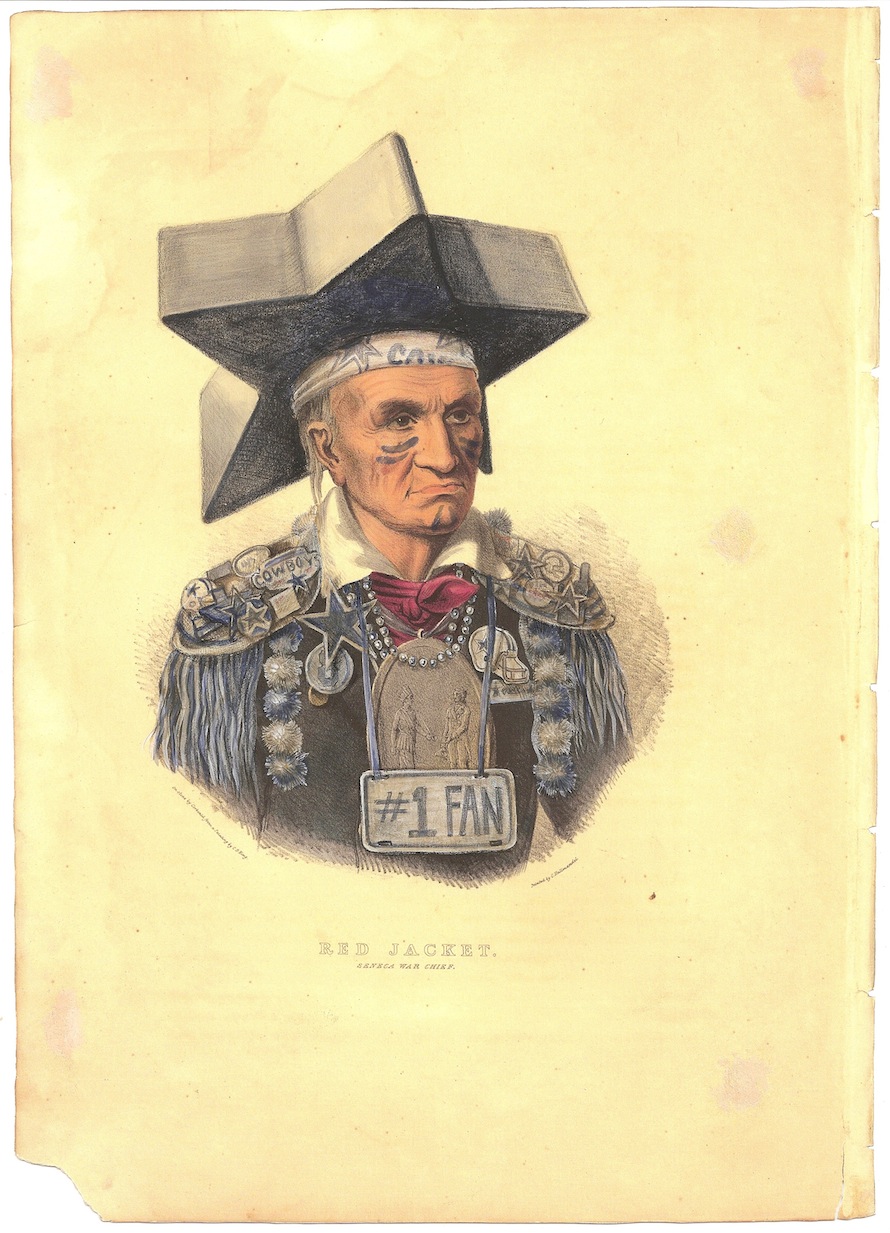

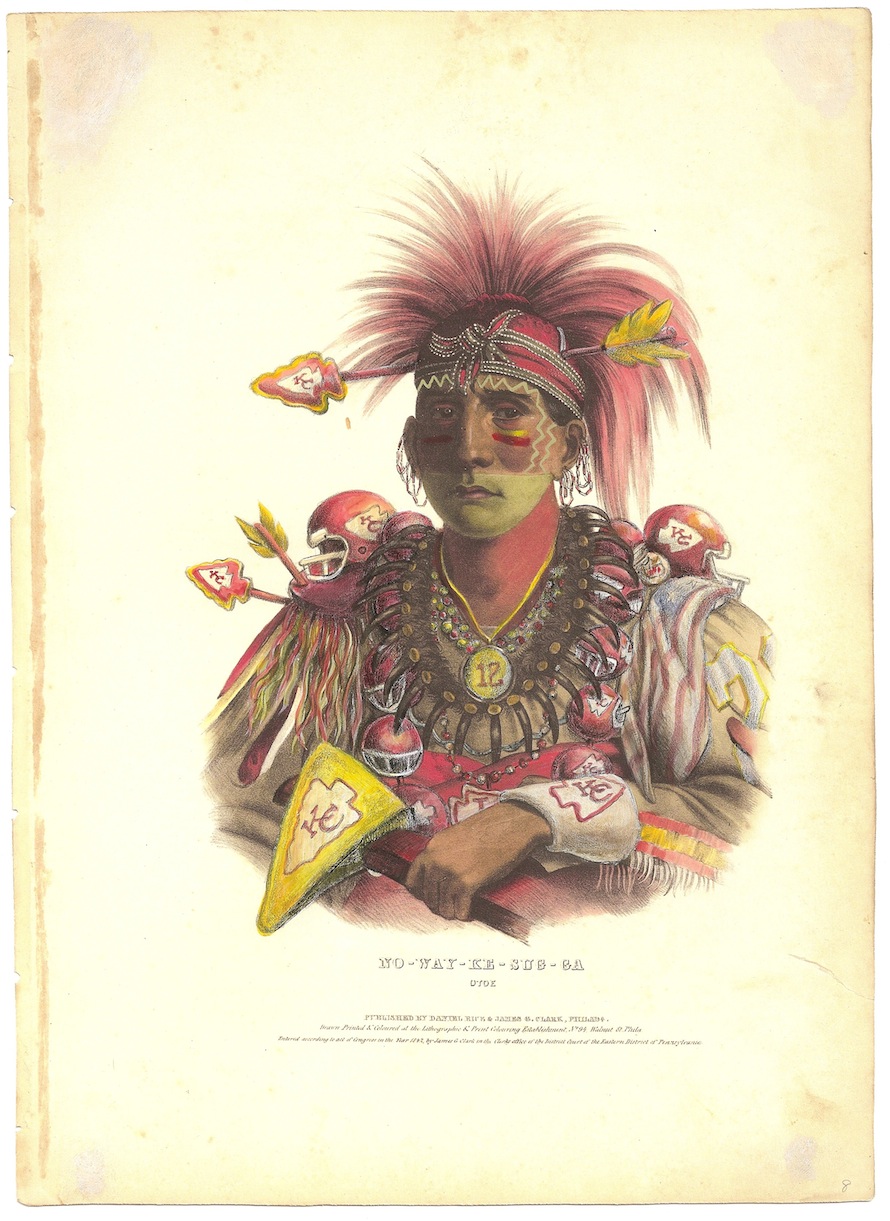

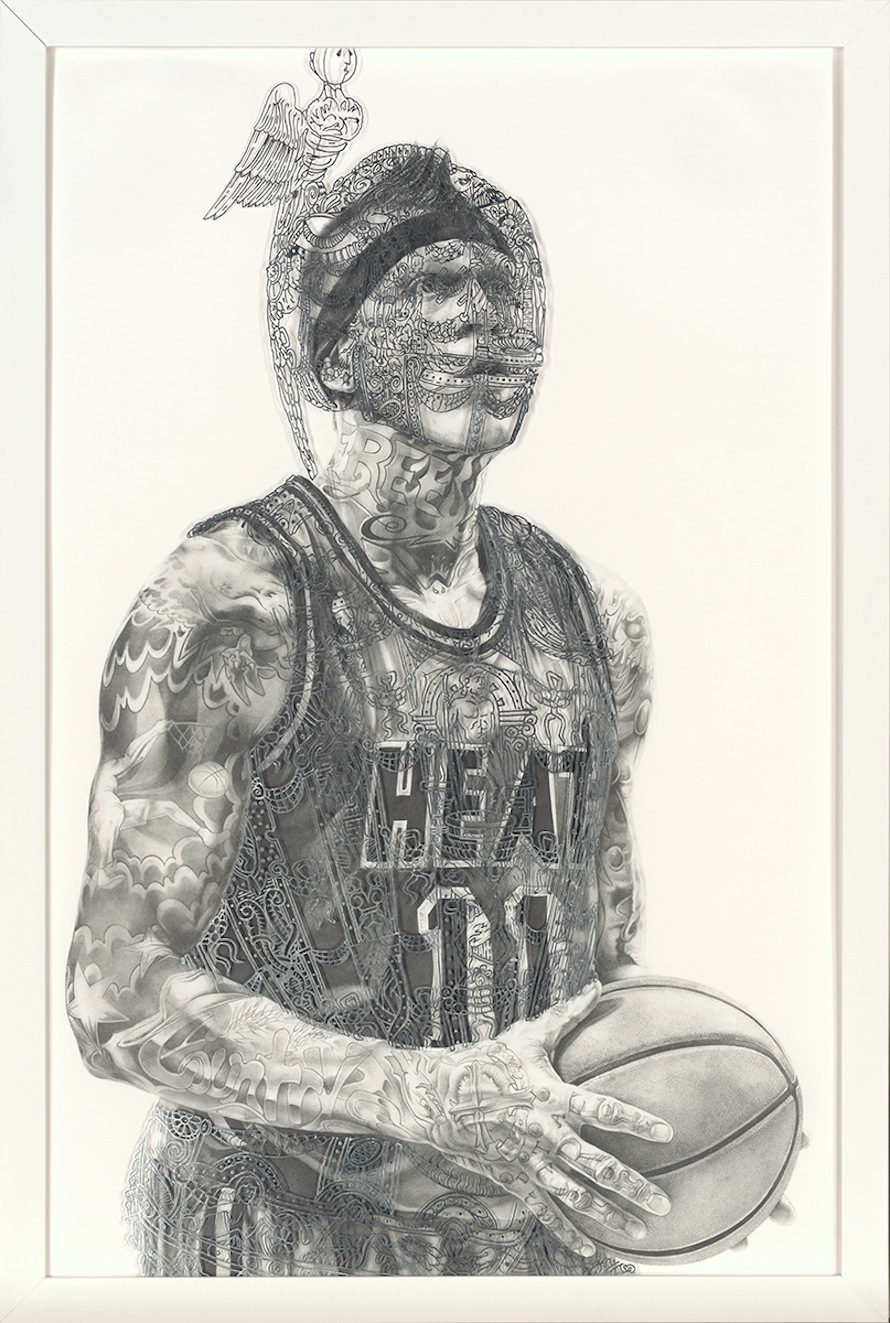

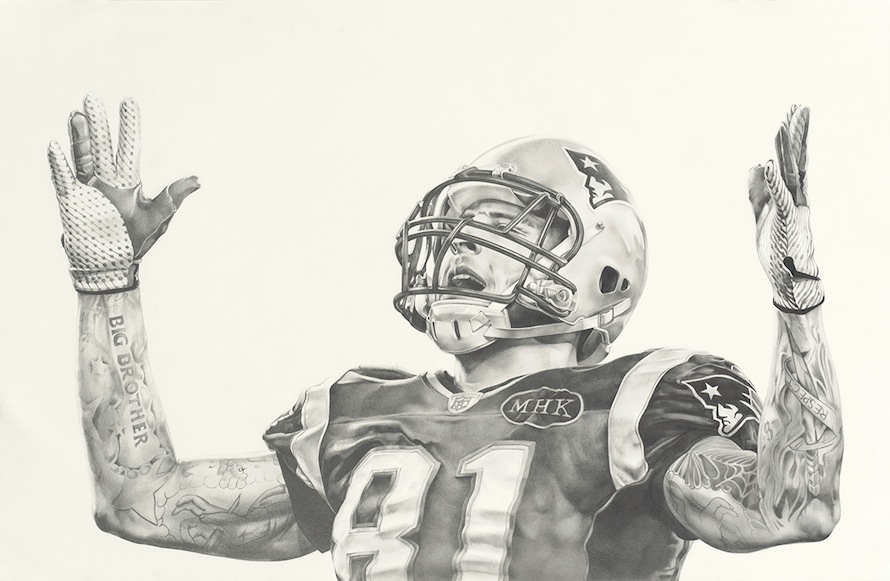

The business and madness of modern sports appear, through subtle augmentation, in classics of American art.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

The Morning News: How did this series begin? Are you a sports fan or athlete yourself?

Geoffry Smalley: Well, it was a slow and very natural development. I’m a huge baseball fan, though a sports fan in general? Not so much. As a kid I used to draw loving pictures of my favorite ball players for hours on end. As I grew older and started to think more critically, I became increasingly aware of the problems of sport—from the hero worship to the crazed fandom to the big business-driven madness. Continue reading ↓

“Past Time” is on view at Packer Schopf Gallery, Chicago, through July 12, 2014. All images used with permission, all rights reserved, copyright © the artist.

Interview continued

This questioning lead me to read books about the meaning of sport, sociological studies of sports fans, and the role of sports in America, which shed incredible light on corollaries between the Industrial Revolution-era development of this country and its three main sports. Really, it’s more about the American ethos than sport specifically. And so it began. While I listened to baseball on the radio.

TMN: Is it possible anymore to separate pro sports from the business of pro sports?

GS: In one sense, no. And in another…yes. If you listen to sports talk radio this dichotomy plays out daily. Right on the surface is the passion, without purpose, which allows people to remain fans. I mean, fan is just short for fanatic. Fans have the capacity to devote incredible amounts of money, emotion, and brain space to their heroes and their parochial loyalties. Fandom allows people to be a part of a group, to identify with comrades in a unified front. But then that passion becomes vitriol when an athlete or team doesn’t live up to the money paid or spent. It’s all intertwined in such a way that there is no line of division. At the same time, the three hours spent watching a game provide the distraction and the clarity people seek to escape their daily reality, and that experience can be pure.

TMN: Who are your heroes in art?

GS: Wow, so many. They change drastically throughout the years, and I look at a lot of people that don’t necessarily directly influence my work like Luc Tuymans, Kerry James Marshall, Wim Delvoye. But I always come back to Oyvind Fahlstrom, Ray Yoshida, and Magritte.

TMN: Who do you struggle to understand?

GS: My dog Chopper.

TMN: How does Chopper see the world?

GS: As food and not food.

TMN: You work as an art conservator. How did that influence your choice of images/styles to alter in this series?

GS: In as big of a way as could be. Working a full-time job and maintaining my studio practice has necessitated shifts in my working methodologies. In my day job, I work mostly with antique imagery. And sometimes I need to replace lost pigment or lost sections of images, a job that requires my hand to be as invisible as possible. That kind of chameleon approach worked its way into my studio as a way to make a seamless transition from work to (art)work. I also started to really think about the era and the art, peeling back layers and forming relationships between, say, Thomas Cole’s manifesto and the rise of baseball in the late 1800s.

TMN: What was the first piece of art you ever sold?

GS: Oddly, this topic just came up. A week ago, a good friend and fellow artist, John Sabraw, posted an image on Facebook of the painting he bought from me in 1995. It was his first art purchase and my first sale. I never knew his motivation then, but he described what he saw in the work, and in me.

His comments about how my confidence inspired him really mean a tremendous amount, especially because, like many artists, my inward self and outward self are sometimes at odds. It was a huge ego boost and validation then, even more so for different and deeper reasons now.

TMN: Are you a Cubs fan?

GS: Yes.

TMN: Why on Earth?

GS: Like a misplaced mole, or a crooked nose, some things are genetic. Thanks a lot, Mom. (Kidding…love you!) Love the underdog in all facets of life.