Growing up, photographer Kendall Messick only knew his neighbor, Gordon Brinckle, as the projectionist at the local movie theater. When they met again in 2001, Messick learned that Brinckle had been working at another theater, The Shalimar—a fully operational tribute to cinema’s great movie palaces constructed entirely in his basement, with even a working organ.

Messick’s new book The Projectionist (Princeton Architectural Press), and his documentary and traveling museum exhibit of the same name, find a lively human spirit in Brinckle’s obsessions, bringing to light the work of an artist on the scale of Henry Darger, and one who worked with a giant heart.

Messick’s documentaries have been featured in various film festivals and have been widely broadcast on PBS. His photographs reside in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Smithsonian Institution. All photos copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

Give us an idea of what it was like the first time you walked into Gordon’s basement theater as an adult.

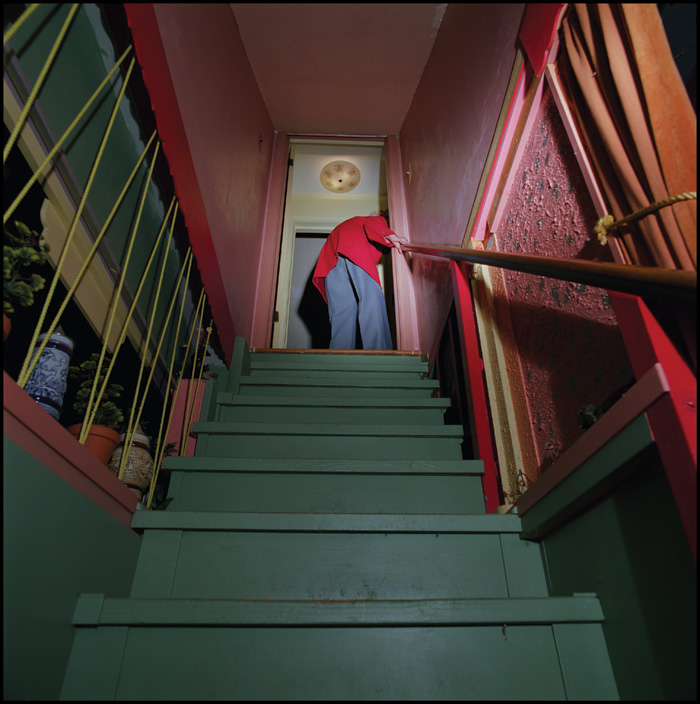

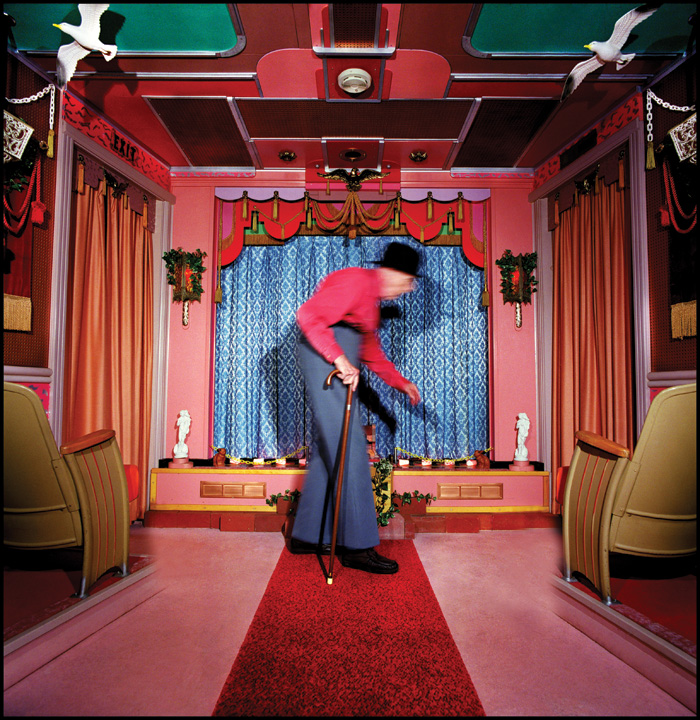

I was unprepared for the experience of seeing the Shalimar Theatre during my first visit as an adult. My childhood recollection had consisted of little more than a vague impression of a stage, theater seats, and a projection room. However, the reality of Gordon’s “theatre of renown,” as he lovingly called it, was beyond anything I could have imagined.

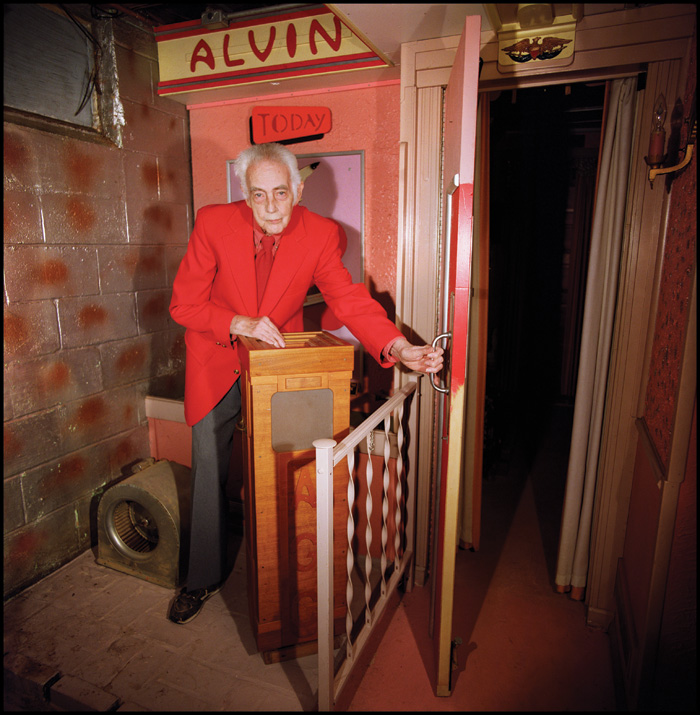

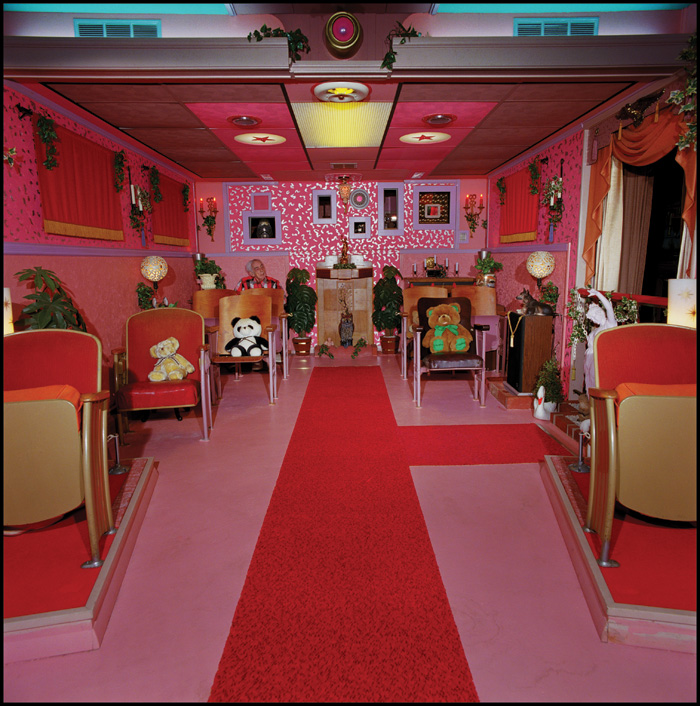

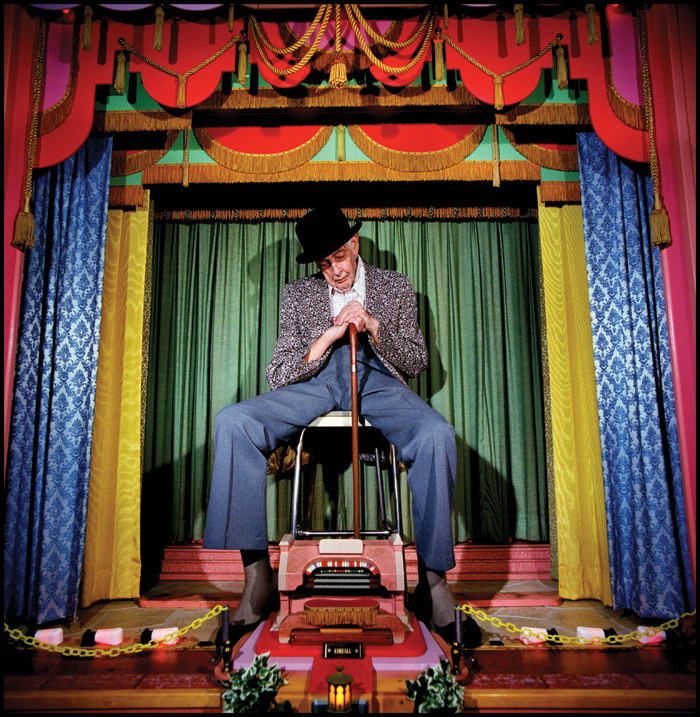

His movie palace in the basement was a complete environment, containing all of the elements one would expect in an actual movie theater—a marquee, box office, auditorium, stage, screen, organ, and a projection booth complete with projectors. Everywhere I looked, there were intricate details in the design and decoration that spoke to Gordon’s passion and obsession. His quirky choice of color and design as well as his unexpected combination of styles ranging from art deco to mid-century modern suggested an imaginative, artistic vision that was clearly original.

I distinctly remember feeling that day that I had been transported into another world—a world that was fanciful, imaginative, and surprisingly womb-like. In the tradition of the movie palaces of the past, Gordon had decorated the auditorium for Christmas prior to my initial visit. This added layer of ornament took his opulent theater to new heights, leaving me with questions about the quiet man that was behind such a creation.

How frequently did Gordon show movies at the Shalimar?

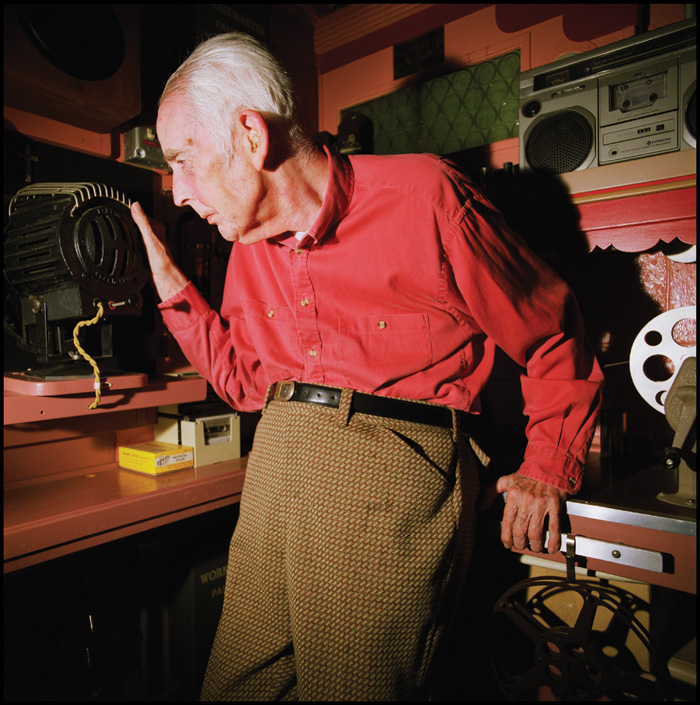

Gordon rarely screened movies in the Shalimar, despite the fact that his basement theater was “fully operational,” having been outfitted with a working projector, movie theater screen, extensive sound equipment and myriad special effects lights. When I asked him on several occasions why he had not screened more films in his theater, his answers were vague at best. This confirms my belief that while for Gordon it was critical that movies could be projected in his theater, it was never a desire to project that prompted his creation. In his writings about the Shalimar, he expressed his desire to preserve the experience of the movie palace through the Shalimar. For him, it was a memorial and a museum. It should also be noted that his night job as the local projectionist at the Everett Theatre for 33 years fulfilled his desire to project movies.

Before the book and documentary, was the Shalimar known around town? How was Gordon perceived by his neighbors?

The Shalimar’s existence was not widely known around town. I don’t believe this was the result of any conscious attempt of Gordon to keep the theater a secret. Instead I attribute it to his quiet, introverted demeanor. In the opening line of The Projectionist documentary, Gordon states, “I’ve been a loner my whole life. It wasn’t that I didn’t get along with people, it’s just that I was too busy fooling around with movie equipment at home.” I believe that this aspect of his personality made it difficult for neighbors to get to know who Gordon truly was as a person. During early interviews that I conducted with him, he shared that during the late ’40s, ’50s, and ’60s, as he worked as the projectionist at the Everett Theatre, he was commonly known around town as the “movie man.” He admitted that many people around town never remembered his name so the moniker stuck.

The documentary film was completed in 2003 and I organized a premier screening of the film in the Everett. Many of the townspeople attended the screening, and Gordon and his wife Dot were able to see him on the big screen for the first time. This was a magical moment for them since he was acknowledged by many of the locals. As I listened to the reactions of the townspeople that evening, it was confirmed just how few people knew of the Shalimar’s existence; many of his former neighbors shared that through the film they felt as if they knew him for the first time.

The portraits taken in the basement seem more intimate than the ones shot during everyday life. As you worked together, how did the relationship evolve? Did the performer in Gordon, the one that seemed to come out in the basement, exist upstairs?

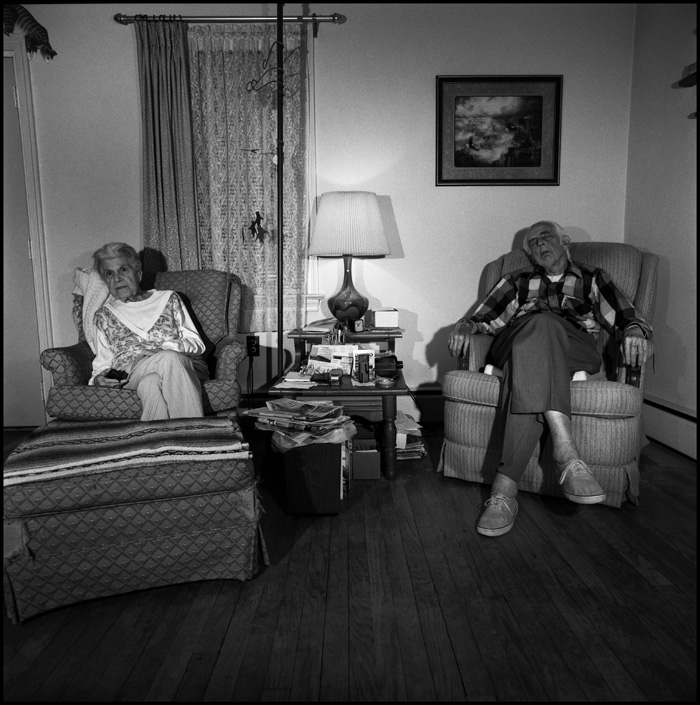

I began working on The Projectionist in 2001 and continued through Dot and Gordon’s deaths, which occurred in late 2007. The fact that I grew up across the street from the Brinckle’s would suggest that we developed a close relationship from the time I was young. To the contrary, the close relationship with both Gordon and Dot began in 2001 when I began working on the project. That said, the Brinckles were extremely private, and I am certain that it was their sense of who I was having watched me grow up that made the project possible in the first place.

Not surprisingly, Gordon and I became extremely close as the project progressed. We spent many, many hours working together one-on-one documenting and making photographs of him and the Shalimar, and this intensified the relationship significantly. The process of making such portraits with a person of advanced age requires more work and patience than the casual viewer would realize. The physical constraints alone add layers of complexity to the effort required to construct each image. This long term collaboration with Gordon coupled with the our mutual realization that we had so many things in common as fellow artists are at the heart of the intimacy that came to define our friendship.

While most of Gordon’s life was quietly spent behind the window of the projection booth, it became apparent to me that he harbored a desire to perform. This aspect of his personality comes through clearly in the color photographs that I made of him in the Shalimar; however, it is not so obvious in the upstairs images of his daily life. I attribute this to the fact that he was always at his most comfortable in the world that he had created. The Shalimar was the one place where he visibly came alive and his imagination thrived, allowing his oft-hidden desire to perform to come through.

What did Gordon’s wife Dot think of the theater?

Dot supported Gordon’s obsession with his movie palace in the basement from the time they were married. She was the breadwinner in the household, lending financial support to his endeavor, and she also helped him when he needed an extra pair of hands as he worked on The Shalimar over the years. In her final years, she was clearly proud of what Gordon had accomplished and happy that his work was going to live on and be appreciated.

How do you see Gordon as an artist? Do you see connections with outside artists, people like Henry Darger?

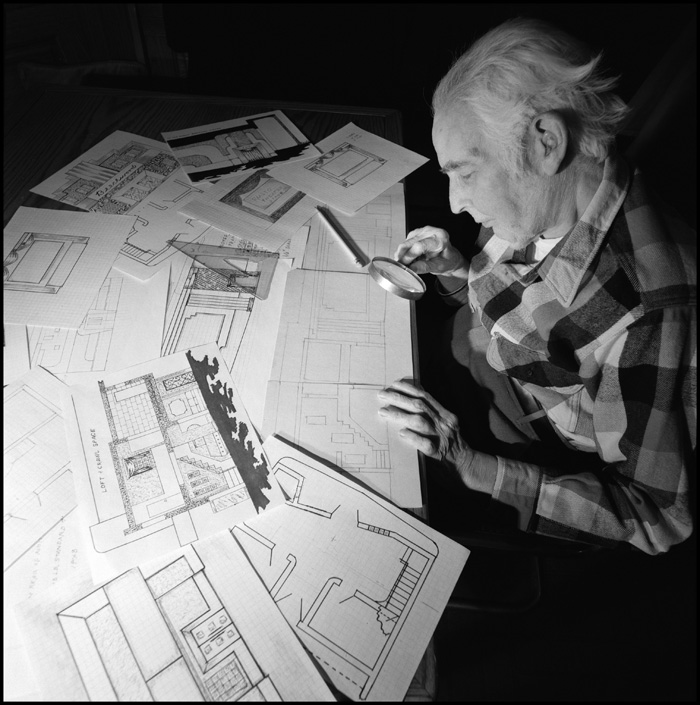

I definitively believe Gordon was an artist. His lifelong dedication to drawing, designing, and building movie theaters belies an obsessive vision and focus characteristic of some of the greatest artists of our time. Furthermore, his creative approach was holistic, including the design of theater tickets, stationary, and usher uniforms.

An early detail highlighted to me the fact that Gordon was an artist. As I looked over early photographs of the first theater construction that he had built in his parent’s basement in the ’30s, I discovered that he was not content to simply build and decorate the theater. Instead, he would constantly change, enhance, and evolve his environments over time. I believe that his lengthy process of working and reworking his theaters can be likened to the creative process followed by many successful artists working in a range of mediums.

There are a number of obvious parallels between Gordon and outsider artists such as Henry Darger. In the case of Gordon and Darger, they both worked in relative seclusion throughout their respective lives creating artwork that was unconventional, obsessive, and singular. Additionally, neither had any formal training of note, and both were working clearly outside the mainstream art world. It’s my belief in the importance of Gordon’s body of work that compelled me to not only document but also preserve his legacy for future generations.

Where is the Shalimar now?

Gordon’s nagging concern in his final years was the fate of his movie palace. He was convinced that it would end up in the trash when the house was ultimately sold. This fear led me to contract with a museum fabrication and display company in Delaware to save The Shalimar one year prior to his death. This involved creating architectural plans for the theater, disassembling it piece by piece, and rebuilding it exactly as it had existed in the basement in a modular way. To date, the entire front half of the theater, including the walls, ceiling panels, proscenium, stage, screen, and loge area have been reconstructed and crated as part of a traveling exhibition. My documentary of Gordon is the featured attraction and is screened in the theater within the exhibition. The remaining elements of the theater (e.g., the box office, organ alcove, back walls) have been inventoried and crated with the intention that once additional financing is available the entire theater can be reconstructed.

Currently, the reconstructed Shalimar is crated in a climate-controlled storage facility—ready to be transported to the next museum exhibition of The Projectionist!