The Young Women of Tehran

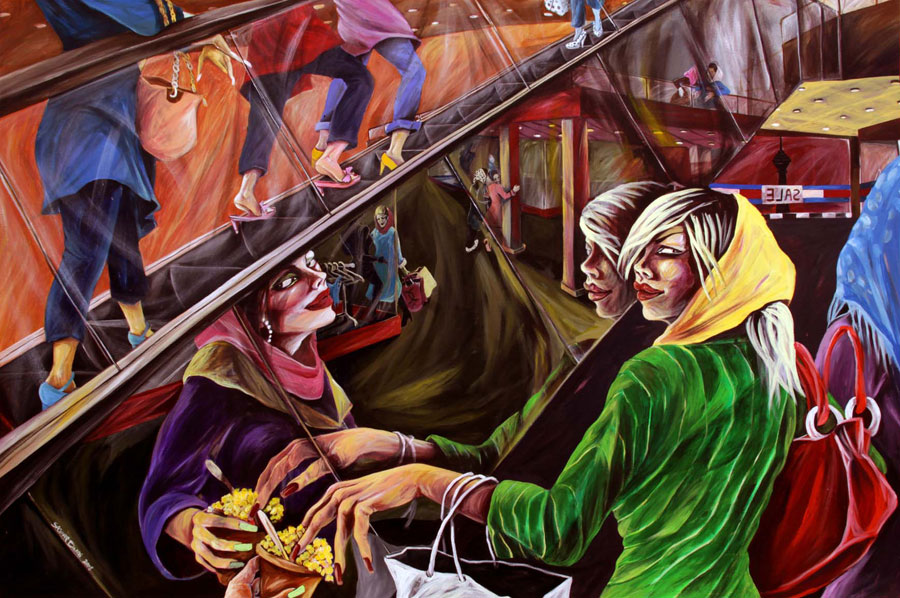

Contradictions abound in Iran's struggle with modernity. The women in Saghar Daeiri’s paintings lurch from their frames to assert their self-expression, taking us into a world of bazaars and malls that existed long before rioters in the streets began Twittering.

Interview by Nozlee Samadzadeh

Why did you decide to paint women shopping?

My main theme is young women in the 1360s, 1370s, and beyond [this corresponds to the 1980s and 1990s in the Gregorian calendar—ed.]. These young women are depicted in the context of and confronted with Tehran as a city that is superficially suspended on the verge of entering a world which is trying to accept various elements of modernity and perhaps behavioral modernity. In Tehran, which in the vernacular of the masses could be called a developing city or a third-world city, this confrontation occurs objectively and palpably in streets, coffee houses, shopping centers, media centers (cyber cafes, bookshops), etc., all of which involve elements and activities that convey some aspect of modernity. Continue reading ↓

All images courtesy and copyright the artist, all rights reserved. Translated from the Farsi by Mansur Samadzadeh.

Interview continued

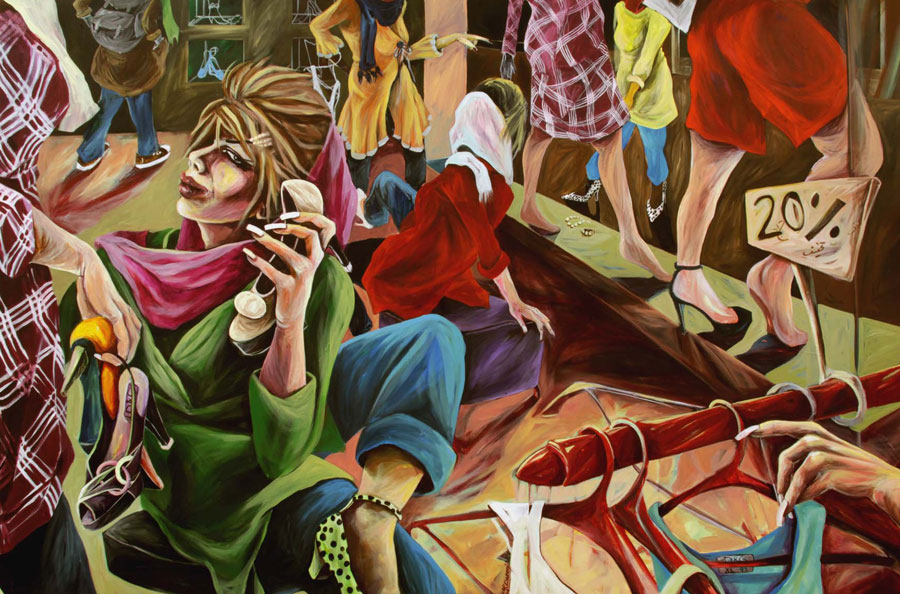

Moreover, I myself am a woman of ‘70s-era [1990s era—ed.] Tehran who still walks around its streets, sometimes stopping at a coffee house for coffee, sometimes going to malls. So the reasons and the principal subjects that have formed my paintings are my crossing paths with the young women of Tehran and the young women’s inclination to project as modern an outlook of themselves as possible, as well as my encounters with the superficial currents of modernity in Tehran, a city that has not yet tasted modernity in its true sense.

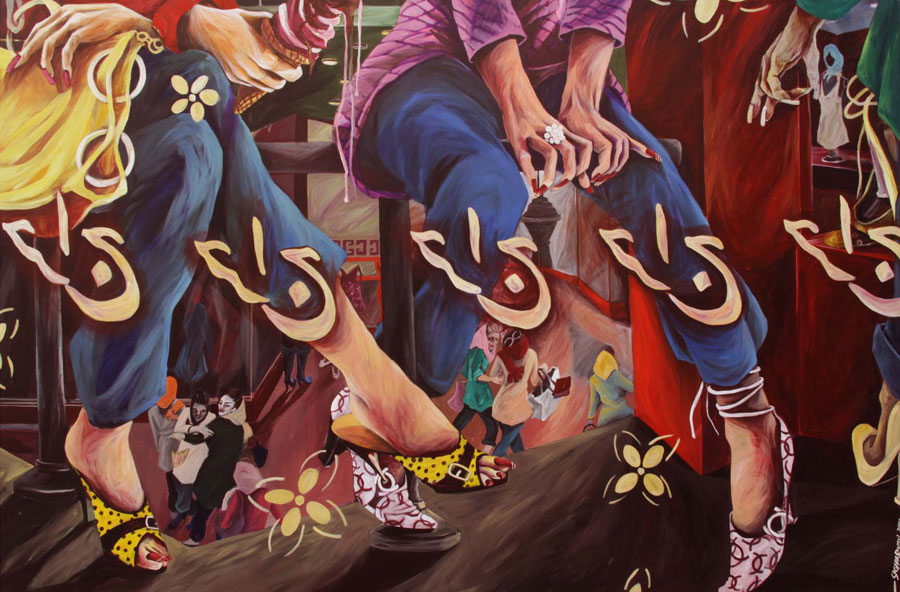

Thus my paintings could be summarized as recounting the external and internal lives of young women in Tehran, and the societal group that those young women have defined for themselves, in the process of whatever constitutes and manifests the identity of their current outward appearance.

These women look almost grotesque, with the emphasis on blond hair, thin eyebrows, plastic surgery band-aids, and jewelry. How does this compare to the women seen in the streets?

What is being expressed in my work is a reflection of a societal factuality (which cannot be inherently factual) that has taken shape about a particular mode of expression and appearance for young women, and has served as a model for a certain criterion of beauty. Therefore, it is an unavoidable objective point that on occasion some aspects of the paintings and figures may appear to a viewer to be exaggerated or caricature-like.

In fact, my paintings are societal critiques that are shaped from the very fabric of the society, and I cannot depict something that is contrary to what actually exists. Here the topic is capturing and expressing a “consensus ideal” for “beauty” among young women in Tehran!

Are these women happy?

What shouldn’t they be happy? Although a specific commonly-adopted standard of beauty may not be acceptable to each and every individual, in the final analysis such standards are adopted with the objective of creating gratification and acquiring the feeling of gratification. This is in spite of the fact that this pleasure is not permanent, and rather that it is inherently temporary. What is important is that this derivation of pleasure is momentary and fleeting because my expression is one of the pedestrian consumer life.

Where are the men in your paintings?

The presence of women in my paintings, in spite of the lack of male physical presence, has so far been a quite suitable setting for triggering thought and imagination about the role of men in society. If you look closely at my paintings, you will notice that men’s presence indeed exists in various elements suggestive of men, at time erotic male indicators that are meaningful in context and composition, and even the typical male-type ogling of the merchandise by the young women themselves. So, in my paintings, the profound presence of men is in fact visible in the different roles played by the women such as their poses and the way they look at each other or size up one another.

How has the aftermath of the elections affected your views on this series?

Unavoidably, my perspective has shifted somewhat. However, in the context of my paintings, there is only a single relevant issue: the specific societal angle that I am investigating, which existed before the recent events, has not lost its importance in light of them, and will continue to exist. The specific consumer class that is the main subject of my work has always existed and is not specific to a one- or two-year duration to undergo change because of a social event. This is a wave that is being critiqued by people like me, a wave that more than any other factor is related to cultural vacuums and a particular worldview about modernity, the impact of fashion, and so on.

Are these women trying to be American, or trying for a sense of distinction in spite of the veil?

First of all, the current societal theme and its widespread imitation are not necessarily related to the U.S., the North Americans, nor to any other specific country. If we set out to investigate the origins of such influences, the European countries, especially the ones generally known as the originators of fashion and the countries whose fashion models are accepted ideals of form and beauty (France, for example) play a much more significant role. Even the developing countries neighboring Iran play a more significant role than North America.

Secondly, I can consider the scarf as just one other fashion-preference product with aesthetic connotations that these individuals are consuming. When young women in Tehran are dressing up, the scarf indeed plays an important coordination and composition role, much like a bracelet, a wristwatch, a pair of pants, or a particular name brand that has become fashionable!

Thirdly, the abundance of attention that the young women lavish on themselves would not exist if this were not a means of self-expression and self-assertion. Young women in Tehran find this natural urge to express themselves this way and to seek gratification in presenting themselves as up-to-date, modern, and as followers of fashion. In fact, they see this as a means of being on a par with and comparable to their counterparts in modern countries.

Does these women’s attention to their outward appearance detract from how seriously their words and thoughts are taken?

Exactly! I have personally experienced this about myself. Not being taken seriously is an unfortunate consequence of the nature of these young women’s behavior and actions in society. The general proclivity to consumerism and the urge to consume rather than to produce, causes one’s social awareness, both internally and especially externally, to deviate and go astray. It has caused the young women in Tehran to appear increasingly unimportant, both inside Iran and also from the foreign perspective, with regards to awareness in all societal aspects and finding themselves entangled in advertisement, gratification. Though it must be mentioned that the situation is not necessarily always as stated.

What do you think one of your typical subjects, were she asked, would say about your paintings?

My work is a reflection of the space around me in the mirror of my imagination. To answer your question, I will relate the experience I had while “Tehran Passages” was on display in a gallery in Tehran. A number of young women reacted to my work, and I can generally classify their reactions into two groups. The first group could intimately relate to my work since, from their point of view, they considered my work and the young ladies in my paintings as quite fashionable, beautiful, and modern. They were interested in purchasing my work and they would even ask me questions about the identity of my subjects and other physical aspects of the paintings. The other group, as a direct consequence of encountering themselves in a visual medium captured in a frame (i.e., the young women in my paintings who looked and dressed much like themselves), would go through a difficult struggle bordering on a paradoxical feeling that would at times exhibit itself as self-loathing!

That is why in response to your previous questions I mentioned that this cultural system, and the current ideals that it promotes, are not inherently profound but rather that they are paradoxical and as yet unspecific and unsettled. Those who are living those ideals are in fact involved in a role-playing game, or perhaps they are involved in a consciously or unknowingly clever game for expressing themselves and asserting their existence. As a result, when something is not inherently profound and is predicated on a mere superficial layer, it cannot be influential and consequential in subsequent actions.