by Jesse Ball

30% OFF at Powell’s »Matthea Harvey: Comparing Adam by Ariel Schrag and The Bone Clocks by David Mitchell is a bit like putting a rainbow in a gasoline puddle next to a Hubble Telescope image. They’re both beautiful: one firmly grounded in this world; the other, otherworldly. If you’ve read Cloud Atlas, you won’t be surprised that The Bone Clocks is the otherworldly novel. However, from their radically different vantages these are both novels concerned with the endlessly interesting issue of the mind/body divide.

Mitchell has clearly found a form he enjoys, and it involves leapfrogging timelines. He’s a narrative braider, but in The Bone Clocks that braid is often on the verge of unraveling. The conceit he uses is that alongside humans living in human time there are horologists and anchorites. The horologists live somewhat normal lives, but when they die they wake up 49 days later in a new body, in a new time (usually in the body of a child who has just left his or her body), and with their memories intact. The anchorites have to take over human bodies (only the bodies of children with psychic tendencies work, and the host soul dies when the anchorite moves in). There’s a century-long battle going on between these two groups, which allows Mitchell to set the book in 1984, 1991, 2004, 2015, and 2025.

Sounds interesting, right? I’m all for sci-fi (as a rule I say bring on the aliens, time travel, and interplanetary war), but Mitchell makes his first human protagonist, Holly Sykes, such fun that you just want to stay in her head as she delivers gem after perceptual gem:

“There’s a splish of a fish. I see where it was, but not where it is.”

“Okay, so she’s mad as a sack of ferrets.”

“The English Channel’s Biro-blue; the sky’s the blue of snooker chalk.”

“A hawk thing’s a speck in the sky.”

“The wood sounds like never-ending waves, with rooks tumbling about like black socks in a dryer.”

If you ask me, Holly Sykes is an excellent poet. I’d like Mitchell to write a whole collection from her perspective. I feel like I’m already writing the blurb for that book, which is not something I’d usually volunteer to do.

I won’t spoil the ending for you—there’s a giant battle between the horologists and the anchorites, then we end up back in Holly’s body again—but in the latter chapters, my investment in the story waned somewhat. The problem I had with The Bone Clocks may be part of its genius. I found it hard to care much about the horologists, the anchorites, and their battle because I was less attached to Marinus (who was born in 640 AD and has had 36 identities, of whom the reader encounters Yu Leon Marinus, Lucas Marinus, Klara Kosov, Pablo Antay, and Iris Marinus-Fenby) and the other body-hoppers. Perhaps I found Marinus less appealing because he/she necessarily has a broader perspective than the bewildered mere-humans. I would have liked to see Marinus struggling with a craving for a Toblerone in 520 BC, but alas, that was not to be. Marinus states at one point upon waking, “I can’t remember which self I am,” and I felt like chiming in, “I can’t remember who the hell you are either!” Maybe a character map at the back of the book would have helped. Or maybe I got lost because as I was reading The Bone Clocks, my sister’s three-year-old twins were running around the Christmas tree.

On to Ariel Schrag’s Adam. This is her first novel—previously she has published a number of excellent autobiographical graphic novels. The hero in this book is the titular Adam, a teenage boy who has some pretty awful friends who are starting to exclude him from their “couples” activities, and a cool older gay sister, Casey, who has finished her first semester at Columbia. To escape his loser life and improve his chances of getting a girlfriend, Adam goes to live in Bushwick with Casey and her friends for the summer. Adam feels very real in his concerns and perceptions:

The lights from cars ran across his wall, soft sounds in the distance. The objects in his room were distorted, anonymous fuzzy gray blobs that looked alien and out of place. He liked finding the weirdest blob, usually two things melded together, and concentrating on it hard, feeling his brain working as it figured out what it actually was (a desk lamp and an old soccer trophy, a broken PlayStation 2 console and a pile of clothes).

Once the story gets going, Adam finds himself a girlfriend, Gillian; Adam, though, has led her to believe he is a female transitioning to male. I kept wishing that Schrag would switch bodies and tell the story from the point of view of one of the many characters in real confusion about their gender, instead of someone who is pretending to be transgender to get the girl (probably this is because I had just read The Bone Clocks—maybe all reviewers who tend to a certain amount of porosity between real life and fiction should disclose which book they read before the one they are writing about). Still, Schrag paints a lifelike portrait of a group of friends and anchors their exploration of sexual identity in the everyday. Adam’s teenage boy viewpoint can be particularly spot-on when it comes to his sister (talking here about Boy Casey, who is a trans man):

“It’s just, it’s kind of a trans thing, though,” she said. “He’s new to his body, his sexuality. As an emerging trans person, he needs to be free to explore sexual experiences now that he’s not constricted by his assigned gender.”

Casey was doing that thing where she repeats something someone else told her and it sounds totally weird coming out of her mouth.

It’s also pretty great that one of the characters who both the reader and Adam perceive as a cis male for most of the book turns out to be a trans man—but the ensuing conversations and questions aren’t quite as involved as I might have hoped.

I’m choosing to advance The Bone Clocks because I deeply admired its imaginative scope and loony lyric language, but I’m still thinking about how both novels allowed my mind to inhabit other identities and filled me with new questions. When I love/hate/meet someone for the first time, what percentage of that is body and what percentage mind? Would I recognize my husband if his soul landed in the body of an 80-year-old woman? Would my cat’s personality slip easily into a manatee? If I had been born “Matthias” (as my parents thought I would be), would I still be me?

The mind boggles. The body wobbles. Or vice versa.

Kevin: It’s day one, John, and I already feel like I have a month’s worth of things to say about just these two books.

I don’t know that I have ever been more ambivalent about a novel than I am about The Bone Clocks. I love David Mitchell. Cloud Atlas, winner of the first Tournament of Books, is in my fiction Hall of Fame. Mitchell is perhaps better than anyone at merging literary genres with popular ones. His books are so smart and so well written and also great fun. And The Bone Clocks is all that.

[Big breath.]

I think the first four sections of this book are brilliant. Beautifully written and engaging and exciting. Each is a bit of a riff on a literary genre—a coming-of-age story, a posh crime story, a war story, and a delicious combo of your faves: the WMFUN mashed up with literary satire. The sixth chapter is in the environmental, post-apocalyptic tradition.

And then there’s the fifth.

I’m surprised Judge Harvey doesn’t explain how different this chapter is from the others, because it’s central to the experience of reading the book. Basically, the first four chapters read like a realist literary novel. Some nonspecific weird things are happening to the characters, but it’s all in the context of a familiar world. In the fifth section, titled “An Horologist’s Labyrinth,” everything goes absolutely bonkers. It’s not until this point (400 pages into the novel) that the reader understands that underneath this patina of realism is an ongoing, centuries-old battle between supernatural beings.

I am all the way down with that. I think it’s actually kind of a masterstroke to structure the story that way. The problem is, the Horologist chapter isn’t nearly as good as the rest of the book.

Curiously, Mitchell sees this criticism coming, and uses up a Staples’s-worth of black ink cartridges preemptively dismissing it. He makes references to Dan Brown and Jeffrey Archer, and how difficult it is for authors to change genres, and muses about the value of avoiding cliche. In the final chapter, one of the characters even rolls her eyes and points at the improbable deus ex machina that arrives to deliver the denouement and actually calls it a “deus ex machina,” specifically to undermine any pleasure a Times reviewer might feel from describing it as such.

It is almost as if Mitchell had to leave home on a book tour and, facing a deadline on this manuscript, asked Clive Barker to finish it for him. I’m kidding, but it really feels a lot like that. And I say this as someone who enjoys Clive Barker. I say this as someone who has also written a novel about a centuries-old secret war between rival factions that disrupts the lives of ordinary people. But Clive Barker and I aren’t (usually) as good at writing words as David Mitchell. And the words in the Horologist chapter aren’t as good as the words in the rest of this book. By a lot.

It is almost impossible to imagine a character in any other chapter of any David Mitchell book (including this one) shouting “Crush them like ants!” as one of the Doc Ock-like villains does here. It seems almost as improbable, in Mitchell’s hands, that the wonderful Holly Sykes, the one character who appears in every section of this novel, would confront a not especially surprising betrayer with word balloon dialogue like, “They trusted you! They were your friends!”

And then there’s the pages upon pages of exposition, literature’s boner killer. This chapter is loaded with the kind of endless neologism-spiked, telling-instead-of-showing that you expect to find in books next to the airport newsstand cash register.

I suspect Mitchell didn’t want to attempt this conceit halfway. If he was going to do it, he was going to go full-bore fantasy. But I don’t think Mitchell believes that fantasy writing necessarily has to suck. He has at least some affection for his own material.

WTF, John?

John: SMH, Kevin.

Page 516 is when I shut The Bone Clocks, never to return. I had just finished a long stretch of exposition that closes out with one character saying to the other, who has been blathering on about shit I didn’t have any interest in, “If the professor of semantics wouldn’t object … perhaps she’d finish her seminar later?”

Kevin: You hardly made it 10 pages.

John: It felt like a hundred. I didn’t even get to the ant crushing, which is good because I would’ve tried to rend the book in half, which would’ve resulted in some kind of rotator cuff tear, which would’ve made me even more resentful toward David Mitchell. I might’ve even sent him the bill for surgery and rehab.

That degree of anger and upset is due to my extreme fondness for Mitchell’s other work—I think Cloud Atlas would be a favorite for the Rooster Tournament of Champions we’ll just have to do after we have 16 of them. And the Hugo Lamb chapter of this novel might be my favorite crime writing since Patricia Highsmith.

But chapter five was a bridge too far for me and I wasn’t prepared to cross it. I read somewhere that Mitchell means it as a parody, in the same way he’s parodying Martin Amis in chapter four, but even so, even granting Mitchell all the leeway he’s earned and deserves, it stopped me.

Kevin: I don’t buy it. Imagine LeBron James has 70 points through three periods of an NBA game and then decides to brick all his shots in the fourth quarter to make fun of people who can’t play basketball. If a writer as good as Mitchell feels compelled to expose what he sees as a scourge of bad fantasy novels, he doesn’t write another bad one. He writes a good one.

John: Whatever he was trying to do, I ceased to care about what came next. On the other hand, caring about what’s coming next is the chief attribute of Adam, and it’s why I was so thoroughly charmed by the novel. I could pick nits about a lot of things—it’s Schrag’s first novel and it shows sometimes—but my eagerness to chart the path of her protagonist and supporting characters trumped any minor annoyances.

Kevin: I read Adam before I read The Bone Clocks with its Amis parody, but as I was reading Schrag’s book it actually reminded me most of Amis’s first novel The Rachel Papers. There is even a character in the story who is obsessed with an ex-girlfriend named Rachel, and for a while I was convinced that was a tribute.

Judge Harvey says she wishes that the novel, or at least some part of it, could have been told from the POV of an actual transgender person. And I think it’s true—some people might look at this book and say that telling a transgender story from the gaze of a straight, privileged, white male could come off as a bit exploitative. Unfortunately, right now we need characters like Adam to invite readers into a world that might, to some, seem foreign and unsettling. Novels have the power to take us to new places, and a book like Adam, in which the average reader can get a foothold in an unfamiliar world, is a critical step toward eventual acceptance. I’m just glad that it’s also pretty damn good. It’s touching and not just funny, but old-fashioned screwball funny, like Some Like It Hot if Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis were way more committed.

John: Indeed, the novel isn’t just humorous, but comic, which is tough to pull off.

I’m having a hard time articulating a distinction between the books that explains my responses, but here’s an attempt. The Bone Clocks felt like a performance to me, a writer trying to do something, while not entirely knowing what that thing is. I’m not sure Mitchell had a firm target in mind for what the novel wanted to be and achieve. It’s like Mitt Romney running for president.

Adam, while more limited in scope, felt like it knew exactly what it wanted to do. It’s a welcoming novel for readers. Judge Harvey has an interesting choice of words for advancing The Bone Clocks: “admire.”

I see that. Frankly, I’m in awe of Mitchell. But one book lost me. The other held me fast. My vote would’ve gone the other way.

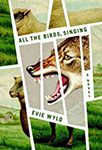

We’re off and running. Tomorrow, another previous competitor, Marlon James, who made it to the semis in 2010, goes up against Evie Wyld’s All the Birds, Singing, our special wildcard selection from one of the many “friend-of-ToB” indie bookstores across America, The Bookstore of Glen Ellyn, Ill.