An Unthinkably Modern Miracle

In today’s health care system, medicine often comes with a strange, Faustian bargain—including a plan for almost everything except the price.

A brief anatomy lesson before we begin. Your urethra is a small tube that (if you’re a guy) runs nine inches from the base of your bladder to the tip of your penis. It snakes down through your prostate gland and between a gap in your pelvic floor, similar to a plumbing pipe. Like tear ducts or sinuses, it is one of the million structural subsystems in the body that you could easily spend your whole life ignoring.

That is, unless something goes wrong.

For example, a plug of scar tissue forms inside your urethra over the course of two decades. You’ve never noticed because there’s nothing to notice; it presents no obvious symptoms. No blood, no pain. Just an imperceptibly small decrease in urine flow year after year. But then sometime after your 30th birthday, you start to realize: you’re peeing a lot. And the more you have to go, the less comes out. Truthfully, you’ve been straining to pee for a while now. Which you figure is just part of getting older. No big deal, but probably worth a call to the doctor next week. Or the week after. Or after you get back from that long weekend. Or, you know, whenever.

The story starts with a routine physical at the beginning of 2013. I see my family doctor, a wry and efficient Brazilian woman, a few times a year whenever I need antibiotics or want to hear that I’m STD-free. For nearly a decade she has presided over my tetanus boosters, my strep tests, my lingering headaches—the small, uninteresting stuff that I assume is a family doctor’s bread and butter.

My current list of ailments seemed typically unexceptional. My knee hurt when I jogged. I wasn’t sleeping great. I had a stye in my left eyelid but it was mostly gone. I almost didn’t mention that I was peeing more than usual, and then only added it as an afterthought. But my doctor took note.

“How much?” she asked.

I explained that I was making jokes on dates about my novelty-sized bladder.

“Well you’re young for a prostate problem. You might want to see a urologist when you get the chance.”

Broadly speaking, I’m a healthy person. I kickbox, I don’t drink much, and I only have a cigarette once in a while. I was never subject to childhood inhalers or Ritalin or even a hospital visit. My blood pressure is great, my eyesight is okay, and I seldom get cavities. So like a dodo bird, ignorant of predators, I saw no cause for concern.

Shortly after my physical I booked an appointment with a urologist I found on the internet. He was a cue ball–bald man in his early 50s who asked me a battery of diagnostic questions and then instructed me to pee into a funnel-like machine that measured my “voiding” velocity. With a sound like an old printer, the device spat out a graph of my bodily function reduced to numbers, which my new urologist spent several minutes examining. He nodded as though a suspicion had been confirmed.

He told me to make an appointment with his secretary for a cystoscopy. When I asked what that meant, he wrote a prescription for Valium.

“It’s linear where it should be bell-shaped,” he said. “Also your flow rate is very low. Like you’re peeing through a washer.”

Then he told me to make an appointment with his secretary for a cystoscopy. When I asked what that meant, he wrote a prescription for Valium.

Similar to a colonoscopy, a cystoscopy is a test that involves inserting a plastic camera scope into the penis and then extending it the full length of the urethra, all the way into the bladder. It differs notably from a colonoscopy in that it’s done while fully conscious. And so, two weeks later, I found myself lying naked on a padded table in my new urologist’s exam room while a stern Jamaican nurse swabbed my crotch with disinfectant. Providing only a cursory “this will sting,” she inserted a plastic syringe into the tip of my penis and shot it full of anesthetic.

“Don’t worry,” my urologist said, hooking up a two-foot-long scope to a TV monitor. “It’s really not that bad.”

To his credit, the experience of having a tube pushed into my penis wasn’t as painful as expected. Painful, for sure, but more invasive. On the monitor I could see a fleshy pink tunnel crawling past like something from a high school science class video.

“That’s my insides!” I proclaimed, my voice a much higher pitch than I’d intended.

There was another surge of pressure and then the pushing stopped. The tunnel had reached a dead end.

“There’s the problem,” he said. “See that?” The tube came out, the science video in fast-rewind. The nurse gave me a stack of paper towels with which to mop up the Betadine antiseptic that had turned my midsection orange-brown.

Back in his office, my urologist explained that he had discovered something called a bulbar urethral stricture: a blockage of scar tissue—like a kink in a garden hose—that made it difficult for me to pee and sufficiently empty my bladder. The cause could have been anything. A fall on a bicycle when I was young, a congenital disorder, or simply bad luck. The condition wasn’t life-threatening, but it would eventually over-strain the bladder and lead to issues including incomplete emptying, urgency, and potentially incontinence if untreated.

“So what happens now?” I asked, trembling.

“The next step is performed under anesthesia,” he said.

To require medical treatment in the 21st century is to enter into a system that has never been truly functional. The mechanics of who provides and who pays for medicine in this country have been under debate since at least the late 1800s, fundamentally inseparable from the larger question of our government’s basic responsibility to its citizens. So unlike, say, sewers or interstate highways, the shape of our medical system has been informed far more by ideological stalemate than by consensus. It’s a fight we revisit every few decades (Franklin Roosevelt and the American Medical Association in the ‘30s, Lyndon Johnson and Medicare in the ‘60s, Hillary Clinton and the Gingrich Republicans in the ‘90s) without ever really concluding. Though its most recent incarnation—President Barack Obama and a bill called the Affordable Care Act—has provoked its own particular mania, it is essentially the same debate, re-tooled for the Internet era.

But if our thinking about the who and how of American medicine hasn’t changed much in a century, the system itself most certainly has. Catalyzed by money, technology, and a growing population, it has mushroomed to such size and complexity as to be almost incomprehensible to the person entering into it. According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, U.S. medical expenditures will account for about 20 percent of our gross domestic product by 2020. That’s about four times what we currently spend on defense, or social security. Add to it the fact that, according to Health Affairs magazine, as many as 31 million people may remain uninsured even after full deployment of the Affordable Care Act—roughly one out of every 10 people. And then there are the labyrinthine financial calculations that dictate which procedures are covered by insurance and what pharmaceuticals make it to market and how many channels a hospital TV should display. Furthermore, we can add medical devices, research grants, colonoscopies as expensive as cars, drug reps paying for golf junkets, and so on. Like poverty or climate change, medicine in this country has grown well beyond our abilities to fully understand it, much less manage it.

To the patient being told he needs surgery, this presents a strange, Faustian bargain. Medicine, by virtue of its ascendency, has become so advanced as to treat almost anything. But if and how it treats you is another matter entirely.

The preeminent authority on urethral strictures is a surgeon who practices at one of New York’s most prestigious East Side hospitals. Like all urological professionals I’ve ever visited, which are not many, he had a straightforward manner that made it easy to don a paper gown and discuss my genitals. His handshake was firm, his bright silk tie knotted wide at the neck. His short examination confirmed my initial diagnosis: I had no prostate problems, no hernia, no testicular cancer, and a bulbar stricture in the span of my urethra just behind my scrotum.

The surgeon’s recommendation was for something called a urethroplasty. This was a procedure that would remove the scarred section of my urethra and reconnect the two undamaged ends. It would be a same-day surgery, three hours under general anesthesia. Following that, I’d have an indwelling catheter and leg-bag for a couple of weeks. “Which sucks,” he explained matter-of-factly, “but there’s no way around it.

“The first thing we’ll need to do is size the stricture,” he continued. A rubber tube would be inserted four inches into my penis and pumped with contrast dye. Then my pubic region would be X-rayed at a low dose. “If the stricture’s less than a centimeter, we can do an end-to-end reattachment. If it’s bigger or more complex, we’ll need to reconstruct it with a skin graft from the inside of your cheek.”

You wake up sometime later, but you wake without your body. Just an upward view of a room and a nurse, like through the eye of a pinhole camera.

Listening to someone discuss the cutting and sectioning of my urethra produced a sensation of extreme lightheadedness. Try as I might to focus on the details of the diagnosis, I kept floating away.

“What are the risks?” I asked.

“The chance of erectile dysfunction is very low,” the surgeon said. “If you want a full accounting of risks—and I’m not saying you should worry about this because it only happens in cases where the urethra is improperly mobilized—then it’s possible to experience a certain amount of penile shortening.”

“How much?” I asked.

“Up to half an inch.”

To the lightheaded sensation this added a fringe of whiteness around the edges of my vision. It felt like a waking dream, a guys-only nightmare.

But the surgeon seemed pleased with the size of the stricture and its positioning for end-to-end surgical access. So I scheduled the procedure.

Certain preparations for surgery are easier than others. It was simple enough to exercise the same yuppie logic I might apply to a vacation. I bought three pairs of sweatpants, roomy enough for a catheter bag. I constructed a Netflix queue hundreds of hours deep. I ordered a week’s worth of fancy cheese from FreshDirect. I felt like an idiot for trying to soothe my fears with shopping, but I did it anyway.

But as I got closer to the surgery date, I realized I’d neglected the most basic of preparations: learning the cost of the procedure. This wasn’t exactly an emergency appendectomy; I was choosing to have this done. Beyond cheese and sweatpants, I was purchasing the surgery itself.

Despite multiple calls to multiple medical offices, no one would give me a clear accounting of the price. The offices I spoke to—the doctor, the hospital, the anesthesiologist—all told me the same thing. We can’t quote a final price because we have to negotiate with your insurance company. And the insurance company’s story was similar. We set contractual rates with healthcare providers but we have no idea what they’ll ultimately bill us. This, it seemed, was how this system worked—less like an actual transaction and more like a bureaucratic turf war. No one knew anything. No one would even discuss a pre-estimate until a few days before the surgery: a non-committal $3,000-4,000 based on “coverage determinations to be made at a later date.” If I wanted my urethra fixed, I was going to have to cross my fingers and hope for the best.

Two months earlier, Time magazine had published a landmark exposé by the journalist Steven Brill entitled Bitter Pill: Why Medical Bills are Killing Us. The longest single article by a single author ever printed in Time, it contained an endless catalog of medical pricing horrors, from families driven bankrupt by routine treatments to gauze pads that cost $77 a box. In one anecdote, a patient is charged for the straps that hold him to the operating table. The article concluded, chillingly but also somewhat pedantically, that healthcare costs in the U.S. are astronomically high in large part because hospitals simply set their prices arbitrarily—with no regulation or recourse. Of patients, Brill says: “They have no choice of the drugs that they have to buy or the lab tests or CT scans that they have to get, and would not know what to do if they did….They are powerless buyers in a sellers’ market.”

Which, of course, was as true in my case as any other. My surgeon was only one man. He operated at only one hospital. The details of the operation, beyond the broad outlines, were largely unknown to me. But part of being powerless is just that: You don’t realize because you’d never think to change it.

Here’s what happens when you have urethral surgery. You arrive at the hospital in a tracksuit with your mom and your best friend in tow. They give you hugs. An administrator swipes your credit card for an “estimated payment” of $3,200 and change. Then you change into a gown and hairnet, and sit in a small room while various people ask you to verify your name and date of birth. You sign consent forms. The surgeon and his assistant come to tell you that everything’s going to go great. Your mom and friend are permitted one last hug and squeeze of the hand. Finally you’re escorted down the hall, around the corner, and through a door into a very bright room in which a team of people are moving purposefully. You lie on a large metal bed and are promptly covered with blankets. The IV goes in. Suddenly you’re floating. Someone puts a clear plastic mask over your mouth and tells you to take 10 deep breaths. Your skin prickles all over.

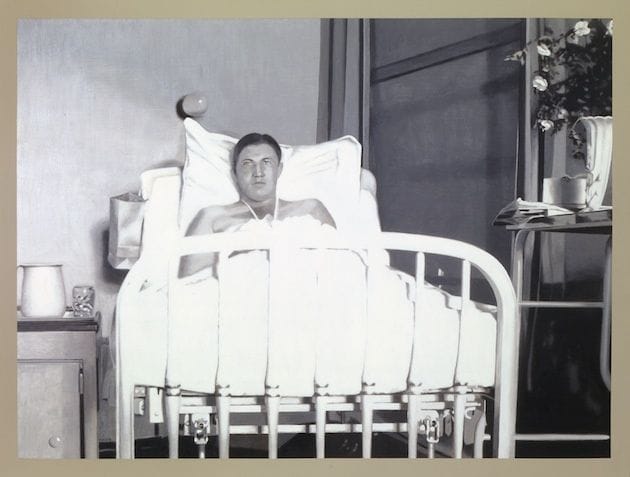

You wake up sometime later, but you wake without your body. Just an upward view of a room and a nurse, like through the eye of a pinhole camera. You drift in and out. A machine next to you beeps every so often and the nurse tells you to remember to breathe. Your mom and friend show up. They touch your forehead. The surgeon appears. He says that the procedure was a success. He also says that you’ve lost a bit of blood and therefore should stay overnight. You nod, you agree, you go back to sleep.

According to the doctor’s report I later obtained, an incision was made from my scrotum to my rectum, through something called the bulbospongiosus muscle, which is responsible for erection, ejaculation, and general feelings of pleasure during orgasm. My urethra was extracted from my corpora cavernosum—an erectile-tissue canal in the penis—and the offending portion removed via “bisection and spatulation.” The two remaining ends were then sutured back together around an 18-gauge catheter. Various pieces and layers were stitched and bonded and closed, my catheter port attached to a drainage tube, and I was done.

During the procedure, however, the surgical team encountered more scar tissue around the urethra than expected. A “dense fibrotic reaction” complicated the incision process and caused me to lose about a liter of blood, which put me just on the cusp of needing a transfusion. The report explained that my bleeding was “ultimately controlled,” but my blood pressure upon arriving in recovery was 88 over 50, typical of someone suffering from extreme dehydration or anaphylactic shock.

I spent two days in the hospital on a morphine drip. My first morning, I passed out trying to get from my bed into a chair. When a nurse came to rouse me for a walk, I could barely go 20 feet. It was as if someone had repeatedly bashed the region between my legs with a steel pipe. Upon discharge, I had trouble standing long enough to dress myself. A friend met me at my apartment and, along with my mother, helped me up four flights of stairs. It took 10 minutes. Sitting required the use of an inflatable rubber donut (it would be six weeks before I could sit on hard surfaces again), and my mobility was further restricted by the catheter rig—an orange tube that extended from my penis to a harness-and-bag system Velcro-ed to my right thigh. I bled through my track pants and later the sheets on my bed. I also couldn’t move my bowels for 96 hours. This was partially the fault of the morphine and Percocet, which both caused brutal constipation, but also because I was simply scared to look. When I finally did, I discovered that my scrotum had swollen to the size of a grapefruit, turned the dark brown of a bruise.

In total I spent four weeks homebound. Friends came by with food, movies, flowers. They took me for small walks around the neighborhood, keeping a hand on my shoulder while I shuffled along. Each night I swabbed my catheter with sterile pads. Every morning I strapped a bag to my leg and plugged myself in. The surgeon and his staff meanwhile monitored my recovery closely. To determine whether my urethra had healed, he filled my bladder with contrast dye, removed my catheter, and then X-rayed for leaks in the repaired tissue. Twice he frowned, apologized, and told me that it wasn’t quite time. But on my third attempt, exactly one month from the date of the surgery, I was pronounced fit for catheter-removal and a return to regular life.

I arrived back at my apartment in a euphoric state. Lights seemed brighter, the weather Arcadian. I threw all my tubes and bags and pads in the garbage. Then for the first time in 20 years I peed like a normal human being. When the stream came out stronger and clearer than at any other time in my life, I felt like I was witness to an unthinkably modern miracle. A basic function of my body had been deliberately and permanently improved by another person’s hand.

It has become popular in business books and magazine articles to refer to Americans as “consumers” of healthcare. What is less often acknowledged is just how extensively our healthcare system has become a consumer of us.

And this is where I dearly wish the story ended. But, of course, it didn’t.

For starters, there was the paperwork. I had naïvely expected some kind of invoice. Instead I got a steady flow of envelopes to my mailbox—small bills for various intubations, X-rays, lab tests and diagnostics, $90 here and $200 there. These were accompanied by an equal number of statements from my insurance company, explaining in obtuse administrative terms why I was receiving the bills. By the time the catheter came out for good, I’d accumulated enough paperwork to fill a shoebox.

Then there was the recovery itself: a gradual and despairing backslide from that first morning of freedom. Although I’d returned to activities like sitting and peeing and even a little jogging, my scrotum was completely numb on one side. Also, I couldn’t maintain an erection for more than a couple of minutes. The muscles and nerves tasked with pumping blood and feeling pleasure were evidently still away on a trauma vacation.

When I called the surgeon to discuss my concerns, he was somewhat more circumspect than he’d first been.

“About 40 to 50 percent of patients who undergo a stage-one reconstructive procedure of this type report transient erectile dysfunction. It’s very rare for that to be permanent. The things you’re experiencing typically get much better within three to six months after surgery.”

“So, like, I shouldn’t worry until October?” I asked.

“What you’re describing sounds completely normal within the course of recovery. I have almost no doubt that you’ll be back to normal by the fall.”

Which was reassuring to hear. I felt that both he and the hospital had taken good care of me. The surgery—as he pointed out—was a success in terms of outcome. It seemed more important to focus on putting my life in order. Getting back to work, back in shape. And I was starting to make progress until the surgeon’s bill, anesthesiologist’s bill, and hospital bill all arrived on the same day.

Thanks to those extra hours in the recovery room and two extra days in the hospital, the total charge to my insurance had been $45,000. Of which I was responsible for $10,000—the sum total of my personal savings from the past two years. And I was to please render payment within 30 days.

Much of the recent debate over healthcare reform has been cast in terms of personal finance. Politicians on both sides of the aisle have cited a 2009 American Journal of Medicine article claiming that more than half of all personal bankruptcies are the result of large medical bills. But while that particular statistic sounds compelling, it actually downplays the full scope of issue. Politifact, a political fact-checking website, crunched the data and determined that during the term of the Journal’s study, the total number of declared medical bankruptcies was only about 500,000. For context, that’s somewhere above gun deaths but below traffic accidents. More recent stats, from a price-comparison startup called NerdWallet, suggest that 10 million Americans with year-round health insurance face the broader and more troubling onus of “medical bills they are unable to pay.” Which is a bit more than double the amount of foreclosures completed during the financial crisis.

If the problem was purely one of financial malfeasance, then it might be easier to rectify. But the reason for crushing medical bills is also, on some level, the reason for aggressive caps on yearly insurance coverage, the reason we have lots of cholesterol-reducing statins but no new antibiotics, and the reason we get more lab tests than we strictly need. All these things are a byproduct of a pay-for-service system that is driven first and foremost by the profit motive. Which, to be fair, is not really news. We live in a for-profit country after all. And a profit-driven medical system is why we have some of the best hospitals in the world, along with cutting-edge procedures for cancer and heart surgery and joint replacement and a whole bunch of other amazing things.

But here again is the Faustian bargain. Medical profit and personal health are certainly related, but by no means are they mutually assured.

It has become popular in business books and magazine articles to refer to Americans as “consumers” of healthcare—in the sense that we increasingly treat care like any other product purchase: researching it online and comparison-shopping until we find the treatment or the insurance plan or the doctor that is best for us. What is less often acknowledged is just how extensively our healthcare system has become a consumer of us. It is as efficient at relieving us of our money as we are at requiring that it do so.

A cursory internet search revealed a world of theories and testimonials on how to negotiate medical bills, but all of the articles and listicles and forums effectively boiled down to two distinct approaches. The first and most obvious was to simply claim I couldn’t pay. So long as I could credibly explain the nature of my hardship, chances were good that the hospital would offer me a discount. The second approach was more aggressive and involved obtaining copies of the hospital’s billing forms. I would have more leverage if I could find a billing mistake or could pick at one of the more extreme charges. Just be warned, one website cautioned, hospitals won’t be very friendly about this.

I opted for the former strategy, dialing the 800 number on my bill. This connected me with a pleasant-sounding woman in what I realized was not a hospital office but a call center. Before I could say anything, she politely reiterated the active balance on my account.

“I’d like to discuss my options,” I said. “This surgery resulted in complications that prevented me from working for six weeks, and that’s been very difficult financially.”

“We’d be happy to help, Mr. Fischer. What we can offer you is an installment plan.”

“That’s great,” I said, trying to smile through the phone. “But I hoped we might be able to talk about a discount for prompt payment.”

“I’m sorry, I’m not authorized to offer that,” she said.

“Not a problem. Could I speak to your supervisor about the matter?”

“He’s not available, sir,” she said.

I asked her when he might be and she suggested I call back next week. So I did. And although I reached a different operator, I had the exact same conversation. This time I also asked for an itemized list of charges, which was a buzz-term I’d picked up from the medical negotiation how-tos.

Sometimes a trapdoor in my mind will open while I’m in a meeting or out to dinner and there I am again—doubled over in pain, clutching my bookcase while my abdomen twists in bladder spasms.

“That should be what’s on your bill,” the second operator said.

“My bill only has category charges. I’m trying to get an itemized breakdown of what those are for.”

The operator said he’d send one out. What reached me several days later was an identical copy of my bill.

Additional research produced mention of a form called the UB-04. Evidently, this document was used by hospitals as the central manifest for billing my insurance provider. Get the UB-04 form—said the patients’ rights message boards—and you’ll get the true dollar amounts associated with your treatment.

A call to the hospital’s medical records department redirected me to their billing office. After a few minutes of hold music, an operator informed me in no uncertain terms that UB-04 forms were not given to patients.

“For insurance only,” she said, and hustled me off the line.

My insurance company said that they didn’t have access to it either, but that the hospital should give it to me.

Technically speaking, the UB-04 form is part of something called the HIPAA Designated Records Set. HIPAA (the Healthcare Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) is an enormous piece of Clinton-era legislation that has a lot to do with patient privacy. You sign a HIPAA disclosure every time you visit a new doctor, allowing them to legally share your medical records with your insurer. But the “P” in the acronym also has more specific consumer-protection benefits. It legally establishes patients’ rights to access any document used to make decisions about their treatment, billing, or insurance payments.

Armed with this information, I again called the billing department. I reached another operator. When she told me that the UB-04 form was off-limits, I hit her with the HIPAA statue and code.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” she said, audibly annoyed. “Can you fax me whatever you’re reading from?”

“I’m legally entitled to this form,” I said. “This is my right as a patient. May I speak to your supervisor?” By this point I was keeping a record of every phone call, every response, everyone’s name.

“He’s on special assignment and not available,” the woman said.

“Can I have your name?”

She offered her first name as Ariel, but wouldn’t give a last name.

“Can I have your supervisor’s name and contact information, then?”

Ariel asked me to hold while she transferred me to someone who could better assist with my request. It took me a moment to realize that the transfer was actually just her hanging up.

To the extent that we are currently having a national conversation about medical care, it is mostly about President Obama’s Affordable Care Act and whether that piece of legislation will be ultimately deemed a failure. The President has promised that it won’t, and will probably spend the remainder of his second term attempting to prove so. And with good reason. Conservative opposition has already shut down the government in an effort to defund the law. Many Republican-governed states have refused to set up insurance exchanges or expand their Medicaid coverage. Various pieces of the law have been altered, delayed, or revised, simply based on its unnecessarily disastrous launch.

But for all the sloganeering—death panels and socialism and Obamacare—that will mark the early 2010s as indelibly as O.J. Simpson and Monica Lewinsky marked the 1990s, the Affordable Care Act simply isn’t that revolutionary. It is basically a stew of incentives and regulations meant to incrementally decrease costs and increase standards. It seeks to turn health insurance companies into something more like public utilities, and applies the same “race to the top” logic of performance-based (rather than pay-per-service) evaluation used in school systems to hospitals. Even its most controversial provision, fining individuals who don’t carry a policy, is not all that different than car or homeowner’s insurance. In other words, the Affordable Care Act is a partial fix, not a fundamental redefinition. Like most of President Obama’s other policy initiatives, it works to adjust rather than re-invent.

If the ACA ultimately survives its opposition and its own fumbles, it will likely come to resemble HIPAA—another wrinkle in an already-byzantine system, solving some problems while creating others. Perhaps if the law had been in effect earlier this year, my hospital bill would have been lower, or my insurer would’ve covered more of that 10 grand. Right now it’s hard to say. The present indicators of its success are distressingly small-bore: the number of users healthcare.gov can support without crashing, the number of enrollees since they fixed the thing, the vague economic speculation that maybe, just maybe, the average price of a hospital visit is beginning to dip.

If you really want to know what the future of healthcare looks like, then a better indicator might be the fact that it is projected to create nearly 33 percent of all new jobs by 2022—effectively replacing manufacturing as a pillar of the American economy. Healthcare, like food or oil, is a recession-proof business with a built-in market as large as the population of the country. The more we can cure, the bigger it gets. No law or series of laws can change the fact that every single person will at some point get sick. That cough will turn out to be more than a cough, that pain more than a pain. Eventually, by choice or by crisis, we will all become its customers.

At the time of writing, my scrotum is still numb and I still owe the hospital $3,000. Erectionwise, I’m mostly getting it up but I’ve still got a ways to go. I’ve also acquired a slight leftward curve. On the plus side, I’m peeing like a champ.

After the lady at the hospital hung up on me, I called my state Attorney General’s office. Then I spoke to a private healthcare advocacy company. I complained to the hospital’s compliance hotline. I tried the financial aid officer who promised to call me back and didn’t. Every service I reached out to proved little more than a set dressing on a soundstage—real enough at a glance but only as solid as required to protect the interests it served. Ultimately I gave up. Or rather, I paid $10,000 to spare myself from an endless bureaucratic fistfight—a not-insubstantial privilege to even have the option.

Sometimes I wake up in the middle of the night, sweating out a panic and wondering what the odds are of falling into the small percentage of urethroplasties that re-scar after a few months. Sometimes a trapdoor in my mind will open while I’m in a meeting or out to dinner and there I am again—doubled over in pain, clutching my bookcase while my abdomen twists in bladder spasms; waking up in the wet spot of my own blood; knowing with perfect clarity that my body will never be a safe place again. My hands start shaking, my head fills with noise, I drift off mid-sentence.

But all I can do with those feelings is put them away. Focus on the “successful outcome” and move on. Not everyone gets to do that. Given the almost limitless number of ways my life could have been up-ended, I am incredibly lucky.

I mean, at least until the next thing goes wrong.