Here She Is…Miss American Idol

Justin! Kelly! Justin!! Kelly!!!! A throng of adoring fans in Burleson, Texas, welcomes Kelly Clarkson and co-star at her hometown stop on their movie tour. Our writer witnesses the mayhem.

The little girl beside me screams to be heard. ‘We love you Kelly! We love you Justin!’ She is vying for the attention of the man with the free passes in front of the Burleson, Texas, movie theater. Her competition is fierce because tonight there are hundreds of other kids just like her, wanting the very same thing. They painted their faces too; they brought homemade signs. So: Does she have what it takes?

The little girl cups her mouth, breathes deep, and tries again. ‘We love you Kelly! We love you Justin!’ Wow, she’s got some pipes. ‘Whoo-hoo!’

Justin and Kelly haven’t arrived yet, but a camera crew from E! Entertainment Television has, and they’re filming this spectacle for Kelly’s celebrity profile. Kelly grew up in Burleson, even worked at the theater we’re packed in front of. The whole area is blanketed with posters for her new film From Justin to Kelly, a musical about two star-crossed lovers on spring break. The movie is implausible and witless, a flimsy Grease rip-off, but none of that matters right now. What matters is that, any second, Kelly Clarkson is coming home.

The man with the free passes walks over to the little girl and hands her two.

‘I got ‘em, I got ‘em!’ she says to her mother, who labors underneath a floppy sign.

‘Y’all can do better than that!’ the radio DJ tells the cheering crowd. ‘This is gonna be on TV!’

The police officers, posted along the perimeter on horseback, yawn.

The perky Burleson cheerleaders stomp on the stage. ‘We say Kelly, you say Clarkson! Kelly!’ [crowd: ‘Clarkson!’] ‘Kelly!’ [crowd: ‘Clarkson!’] ‘We say American, you say Idol!’ And so on and so on until someone’s doing the splits.

The older kids linger around the parking lot, hands stuffed in their pockets. Among them is a young woman in her late teens or early twenties. She is pregnant and just starting to show. ‘I was in the same class as Kelly at Crestview Baptist,’ she says. ‘I’m the reason she started working at Hollywood Theatres in the first place.’

‘How did that happen?’ I ask.

‘Well, Kelly was like, ‘Where do you work?’ And I was like, ‘Hollywood Theatres.’ And she was like, ‘Is it fun?’ And I was like, ‘Yeah, it’s okay.’’ She shrugs—there you have it—and flips her long black hair over to the other side. ‘‘Course I didn’t make the guest list. That’s why I’m trying to win free tickets.’ Her husband, a young guy with a goatee, wraps his arms around her waist and rubs her round belly consolingly. You can tell they are proud to know Kelly—and why not? She has a voice that’s better than the material she performs, and she’s stayed true to her church-going roots. When she appeared on the cover of Us Weekly, looking cute and collegiate, the headline read, ‘I Won’t Starve to Be a Star!’

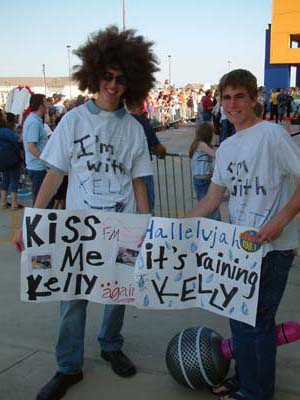

Onstage, in the great tradition of radio contests, two boys make fools of themselves to win free tickets. They sing, tunelessly, ‘It’s raining Kelly! / Hallelujah / It’s raining Kelly! / Hey-ey-ey!’ One of them wears an afro wig. My boyfriend is taking pictures, and every time he catches my eye, he smirks, like, ‘Who are these people?’ He thinks it’s funny, all this hysteria over two hacks he’s never heard of. See, my boyfriend has some kind of superhuman indifference to pop music, television, and teen culture. What I mean is: He doesn’t watch American Idol, which I consider the apotheosis of these things. For me, American Idol is like Kryptonite, weakening my resolve to follow world news, to answer the phone, to do anything but watch American Idol. Which is why I have to limit my viewing. Call it what you will—a guilty indulgence, a willful distraction, a crippling obsession. All I know is that when Clay Aiken sings Journey’s ‘Open Arms,’ I believe.

‘I think I see their limo! Ya’ll yell!’ announces the radio DJ.

Kelly and Justin step from the limo and onto the stage. They smile and wave and blow kisses to the crowd, like the popular kids at the homecoming parade.

‘Can you believe all this?’ the DJ asks Kelly while gesturing grandly to the audience. ‘I mean, did you ever imagine this would be happening?’

‘No,’ says Kelly. ‘Who could have imagined it?’

But who hasn’t imagined it? The fantasy of sudden fame is part of what fuels American Idol. Its celebrity-starved viewers have choreographed their very own stardom, cast their own movies, written acceptance speeches, and savored the crowd screaming their names. But there’s some unspoken agreement that we must treat this as unprecedented—the fans and the cameras and the ceremony—like someone who was in on his own surprise birthday party. And they must tell us, again and again, how great it all is.

‘This is all so great,’ Justin says. ‘We’ve done more things in a year than most people do in a couple of years.’ There was the tour, and then the movie, and then the tour for the movie.

Kelly is nodding. It’s great, it’s great.

The little girl beside me won’t stop screaming. She has won tickets, but now she wants Kelly’s attention. ‘Kelly we love you!’ When I was a kid, Miss America elicited this kind of awe and admiration in a little girl. But these days, beauty pageants aren’t so interesting—not unless they come with a recording contract. ‘Kelly we love you!’ she yells, but nothing. One more time: ‘Kelly we love you!’

Finally, Kelly hears it, looks over, and waves.

Her face lights up. ‘Mom, Kelly just waved at me!’

The mayor of Burleson takes the stage. ‘Kelly, last year we gave you the keys to this city, and let me assure you, we haven’t changed the locks.’ Chuckles all around. Then the radio DJ announces a different ceremony for tonight. Kelly will dip her hands in cement for display at the multiplex—Burleson’s own Celebrity Walk of One.

‘And Kelly,’ the mayor concludes, ‘I hope this is half as special to you as you are to Burleson.’

Somehow, I doubt it.

[ photos by Lindsay Graham ]