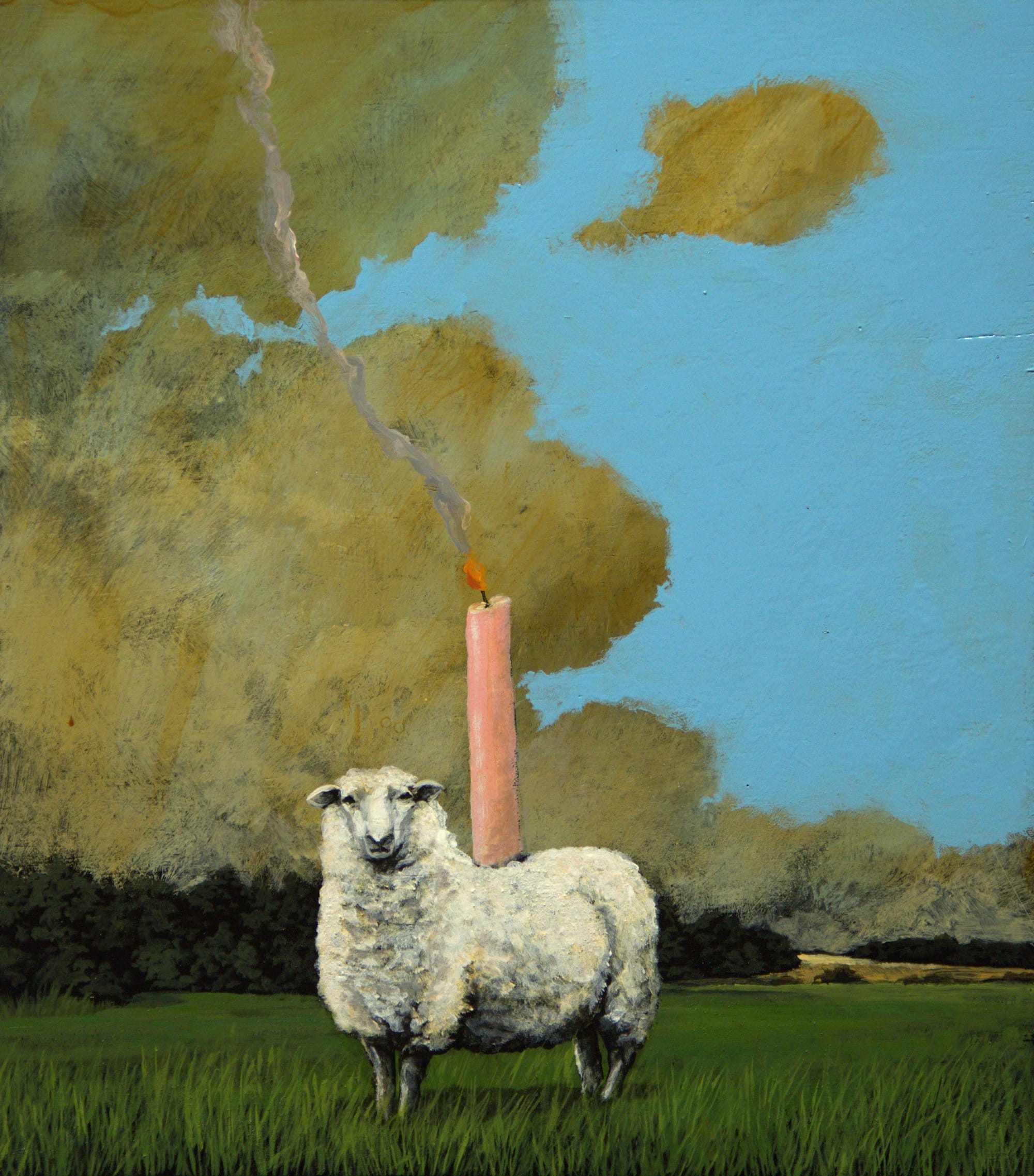

King Lear With Sheep

London traffic, bladder control, and a runaway Cordelia challenge a mostly wool production of Shakespeare’s “King Lear.”

My friend Heather, a director, wants to stage a King Lear in London, and has asked me produce it. She’s been trying to put it on in Massachusetts without much luck as for reasons of hygiene theatre owners are turning her down. The nub of it is that the play stars one man and eight sheep. It is suggested that the US economy depends on beef, and perhaps finds sheep a little threatening.

Lambing season rolls around, to my cost. With it, a stream of Facebook messages from Heather announcing that she has found a warehouse in Lewisham for the performance. These get glummer as I don’t reply, and culminate in “I want a proscenium arch” with a crying emoji, and, as a postscript, the lone word “epidavros.”

I tentatively open her proposal, a 30-page PDF bedecked in 18th-century images of lambs of varying degrees of poignancy. We are, Heather writes, casting one man and eight sheep to question assumptions about the stage, picking up on the thoughts of playwrights such as Beckett. She says it’s an allegorical hate letter, “a deeply nihilistic satire of the theatrical universe.” The sheep are “an oblique comment on the silence at the play’s centre.”

There’s a lot of silence in King Lear it’s true, usually reserved by the sympathetic “sinned against” characters, as well as a lot of mistakes and misspeaking from the more “sinning” ones. Cordelia starts us off, refusing to “heave [her] heart into [her] mouth” by telling her father she loves him, causing Lear to banish her rashly and divide his kingdom between his more eloquent and greedier elder daughters.

The synopsis on page nine explains that the sheep play a Shakespearian cast, and the human actor a harried Director trying to put on a production of King Lear. He is failing because his cast are sheep. But as far as he’s concerned, they performed the play yesterday. Like Lear, he feels betrayed and goes mad, and his typically thespy diatribes become mixed with speeches hijacked from the original play.

No sheep can really be trusted: Even the soft, pharaonic Ryeland cross who outshone the others in rehearsal shits prolifically.

Heather says he favors the most misogynistic and most wounded lines, so I visualize a headstrong, elderly man enlisting the goddess of Nature to convey sterility into a bleating lamb’s womb, as Lear does with Goneril. I’m worried I might find the image galling. But I don’t.

Encouraged, I start to half-agree with some of Heather’s claims. For instance, that Cordelia’s silence in the play amounts to a quite perverse version of integrity: It certainly is awkward when she boasts “My love’s more ponderous than my tongue,” in an early aside to the audience, right before essentially breaking Lear’s heart. I also half-see that by transforming Cordelia into eight sheep we could try and evoke the isolation Lear feels. Cumulatively, I definitely agree with one whole idea, which may be enough for now.

Pushing the other abstractions to the back of my mind, I decide in the meantime to visualize it as a one-man show incorporating a large retinue of hecklers onstage.

Farm animals in the capital must be booked two months in advance: There are always blokes who want to parade through Peckham and tell the story of St Francis of Assisi who will have thought to sign up before you, and London is apparently full of ladies queuing to have donkey parties in their private gardens, preparing to mingle, stroke, and ask agrarian questions.

It can cost up to £500 an hour to rent one sheep, what with transport and licensing. After some pleading, a 20-year-old freelance farmer named Josh makes me the offer of £300 for eight ewes from Surrey Docks Farm, mainly Oxford Downs, of various ages and with different fleece-styles. Josh says that he takes his ewes out everyday in the van on visits to schools, making them comfortable enough with audiences and travel to be suitable for a theatrical tour.

As soon as we have this good option, however, flashier sheep start to come out of the woodwork. Someone’s teenage sister has six devoted bottle-fed lambs. My landlord claims he can get sheep for a fiver if we have a way of transporting them from Wales. My boy’s housemate has the ancient right conferred on him by his school to herd a flock across London Bridge. When I tell my taxi driver what I’m doing with my life, he volunteers that Adam Henson, who reports on rural issues for the BBC show Countryfile, rents out his TV sheep for extra cash.

It’s ludicrous that these sheep are all exposed at once, a scandal that, though of minor importance, reminds me of Operation Yewtree, as though these parodies of innocence had been protected by some social taboo. On top of all this, Heather—it now transpires—has already shot a film with sheep, which required her to drive through grid-less Boston with two unsocialized lambs in the trunk, and she warns me that she will not chance such a journey again. Our nearest alternative is Josh and when I text him he reassures me that his sheep are hardened doyennes of the farm and that it won’t be cruel to put them in fur-lined capes and paper crowns. Finally, a deal is struck.

Trying to research an article that will help fund the show, I come across the history of Surrey Docks Farm. It’s always interesting to read about the successive uses urban space has been put to, or in the case of Surrey Docks (which before WWII was a timber wharf, a receiving station for sufferers of smallpox, and the home of the river fire service), disuse.

In the 1980s, Thatcher’s government set up a corporation to regenerate London’s depressed eight-and-a-half square miles of Dockland, which were once the largest in the world. One thing their new housing projects did was force Greenland Docks city farm to be herded down the waterside to a new farm by Surrey Docks.

Sleep has become the enemy and counting sheep merely strengthens our insomnia.

It was a precarious place to choose for a home, at the time, the water level on that stretch dropping uncontrollably, which given that it was the only body of freshwater in the Docklands was an ecological crisis, not least for the waterfowl nesting along the dock edge. Plus, at one desperate point, the architect in charge hooked pipes up from a disused flood-prone Underground tunnel to a set of granite gargoyles built to spit the excess water out into the depleted dock, thus risking the spread of rat-borne Weill’s disease.

With no other prospects to hand, the goats, sheep, hens, cats, rabbits, cats, donkeys, dogs, geese, and pigs of Greenland Docks nevertheless migrated through the streets of London to Surrey Docks in ceremonial procession, and set up camp there. It’s comforting that our actresses come from a tribe of trouping survivors, though really they don’t, as Oxford Downs are only bred for their meat, known to produce large carcasses from a young age.

Heather and Alasdair Saksena, the talented actor playing our “director,” are already at the farm, where we have eight sheep rehearsing, to be joined onstage by Alasdair and two bottle-fed lambs. Ideally, we’d like three: Cordelia, Goneril, and Regan. But these things should not be hurried, or it seems rather tactless to ask if they can be. Alasdair’s allergies and hay fever make his character seem even more bothered.

The sheep are employed as part of a “mobile farm,” but really they are no better at mobility than Vinny and I, who arrive late, having taken a wrong turn on our Boris bikes off the Jamaica Road. They scamper away from us a few feet, then hover stock still below the neck, like tiny Liam Gallaghers ruminatively chewing the cud on barstools. Their crimped topknotted hair is much more pagan and dynamic than their moderate, largely oblivious temperament warrants, cutting a radical figure in the farmyard and tasseling upward in the warm wind, as if motivated by static electricity.

We imagined catching Cordelia would be easy, but no one has, or will, during that last rehearsal at the farm. Eventually we cast a different sheep in her role. It’s one thing to play a scene as gruesome as the blinding of Gloucester for laughs (“bind fast his corky arms!”) and another to induce a hundred people to snicker uncontrollably at an old man not only unable to summon his child back to life, but unable to even get ahold of her. I’m not keen on the ending being funny.

When Alasdair, as Gloucester, says the word “mutiny,” Edgar-sheep protests his innocence with a harsh bleat.

Then, in these times of cut-throat professionalism, Vinny, who had the job of remembering which sheep is which, quietly sits on the fence now that the sheep are no longer who they were.

In the final scene of the play, the director clasps the junior lead to his breast, convinced that she is dead, lamenting his cruel demands, and begs her to be alive. The only way to ensure such a climax can take place is by type-casting sheep who are more docile because of their age and breed, and even then there’s a high risk Cordelia will wriggle and shit all over Alasdair. That can’t be helped. No sheep can really be trusted: Even the soft, pharaonic Ryeland cross who outshone the others in rehearsal shits prolifically. Neither can we predict whether the ending will be cute or disturbing in performance, but it’s the fact that she’s alive that is important: It makes her an absurd foil to Alasdair’s tragic pronouncements.

Heather pours scorn on Alasdair when he pauses mid dress-rehearsal and starts taking selfies with the sheep on his iPhone and Snapchatting them to all of his “little friends,” but her irritation with the continual distractions that the sheep pose to her (serious) run-through is mitigated by the fact everything is already very askew. She is working nights at the pub and I’m tutoring English as a foreign language to pay for the sheep, spending the rest of our time hanging out at the farm, or at the warehouse. Sleep has become the enemy and counting sheep merely strengthens our insomnia. When I explain the show to my pupil she mutters “Pathetic!” audibly, adding that I have “bitten off more than I can chew.”

We all have our turn with this downtrodden mood, wearing it until someone else needs it more. In the sound rehearsal, Alasdair is surly and affronted to learn that the soundscape for the heath scene will include the canned noises of Hungarian sheep bleating and shaking their bells as he speaks Kent’s warning about “the very wanderers of the dark [being forced to keep] their caves.” Though he is never quite appeased about this, he graciously doesn’t mention it after he witnesses the thorough ruination of Heather’s skirt by Lear, who is massive, unshorn, and has little bladder control.

Mehmet, who is from Cyprus but votes UKIP because he doesn’t approve of the way Europeans drive, instructs me in how to brace scaffolding while driving me and a kino light across London. This is timely because as soon as I get out (and the expression is deceptive, it takes hours) I am set to task doing just that with Pippa, the set designer. Nick rigs the lights up on the top corners of the scaffolding. There’s no off-switch so we’ll have to pull the plug at the mains when the play finishes tomorrow night, or Alasdair and Cordelia-sheep will be latched together forever in the anticipation of applause.

I go to the National the evening before King Lear With Sheep to see Simon Russell Beale as King Lear. Am relieved to find their Cordelia’s integrity unconvincing.

On the morning of the show Alasdair thinks it will do us good to walk for hours to Charing Cross, and I insist on pausing for naps in the garden of each Inns of Court, though I can tell I’m pushing it by Gray’s, where I ask him to sing me lullabies and to identify species of ash tree, theorizing that it’s good for his nerves to be responsible for someone worse off than he is. Then the train down to the warehouse where he at once disappears up a staircase to be alone.

In Britain smoking is banned from public indoor spaces, apart from phone boxes, nursing homes, prisons, and certain rooms in the Palace of Westminster. As everyone is lighting up as they wait around on sofas for the sheep to arrive I wonder if this art collective’s warehouse is actually privately owned. It turns out it is, but people would be smoking anyway if it weren’t. I guiltily recall the ‘no smoking’ signs at the farm and I’m thankful when sheep arrive, mainly because the smell of their shit finally masks out that of our cigarettes and my self-reproach.

Opening night. First to find a seat is Heather’s grandpa, though my father and Alasdair’s parents are also early. The nine sheep (one blessed lamb-sized addition) who are milling around in costume backstage, behind a red theatre curtain, haven’t been fed all day, and we pour grains along the periphery of the low pen we have erected around the stage. This is to encourage them to come through the wings on cue, as soon as Josh opens the gate behind the stage, and it will give them something to do once under the lights.

In truth, I feel a little that we’re wasting their time, especially as time is money, for them more than for any of us. But the seventy seats fill out, and soon so do the sofas and the back. In the front row David Graeber, whose book Debt sparked the Occupy movement, eats a tiny yogurt. I wonder whether our play will be an anarchic hate letter to theatre after all.

The director enters the stage, which is empty except for a single chair, where he sits alone and fidgets, occupying himself with sitting and fidgetting for as long as socially acceptable. He reassures the audience that the cast is on its way, and boasts about their loyalty and professionalism and about the reviews they’ve had together (“‘Apt,’ the Independent”), then with ambitious but uncharismatic gestures moves onto how they “melded” as a group, and checks his watch.

He does so again while insisting he loves his leading lady who looks, according to him, like “a Botticelli painting of Judi Dench.” Much more of this before the sheep are actually due on. King Lear With Sheep may only last 40 minutes but it gives you ample time to assess the ins and outs of every shade of stress, from suppressed, entry-level awkwardness to metaphysical wailing. When Alasdair, as Gloucester, says the word “mutiny,” Edgar-sheep protests his innocence with a harsh bleat, and next to me Heather sinks to the ground. I am glad when “so young and so untender” gets the sadistic laugh it deserves. Alasdair does the blinding of Gloucester (at this point in the show, he plays three parts: the duke, Regan, and Cornwall) and Cordelia gets caught in her cape, at which point Heather, who picked herself up during the heath scene, sinks to the ground again.

It is, at times like this, as though no one had told her there’d be sheep. She appears to have disappeared from the floor by the end, when it’s all gone to plan and I’m brave enough to look down, and I realize that, through her silent torment, Heather must have remembered that one of us ought to arrange a blackout.

In the real Independent the next day, I’m quoted as saying the play is a hate letter to theatre. What I actually said was “Heather just texted me to remind me to say it’s hate letter to theatre, but she’s joking.”

Next, to Jevington, 40 minutes from Brighton on the South Downs, where we will put the play on again with an all-new sheep cast. It seems too much almost: a farmer catching the performance having just become responsible for events at his new pub, and being so moved by Alasdair’s performance that he offers up his sheep. These Suffolk Crosses are the affectionate coastal model, and the director might have to change his tune from “Why aren’t you talking to me” to “Stop headbutting me.” Our farmer’s Georgian barn’s hay bales seat 130, and the décor is nothing like the minimalist, claustrophobic warehouse. We have a three-day run, our costs are covered. Over the baroque sprayed trees curves the proscenium arch that will frame the cast of this tragedy, bleating victoriously.