The Case of the Hungry Stranger

A man is always more complicated than his paper trail—especially when he’s your father, who walked out one day.

The policeman, having just kicked open the back door, missed it. So did the EMTs and the out-of-sorts neighbor lady, her eyes all fear and water. Instead, it took Mom and Sara, with damp washcloths over their mouths, to finally notice it the next day—just sitting there on the table by the recliner in my dad’s house: a standard-sized manila envelope marked in Dad’s sloppy cursive:

Death.

Inside the envelope was a typed letter dated almost exactly a year earlier.

“Dear Bridget, Brendan, and Sara,” it begins.

“This is my latest update on my funeral plans should I decide one day to depart this land of milk and honey […] I have prepaid my funeral expenses. Halligan/McCabe’s will handle it all: a mild wake and an even milder funeral or memorial service whenever you want them—all nonreligious. I don’t care what you do in this regard, but try to make those attending show some degree of remorse over my passing, even if you need to pistol whip them. Also, try to make it a festive occasion, although those gathered will probably think that anyway! If I have any money lying around to finance it, make it a party.”

I try to imagine my mom standing there reading this, Dad now reduced to a terrible spot on the carpet. She pulls a Marlboro Light 100 from her purse—of this much I’m certain—and after shakily clicking the lighter, fills her lungs with smoke.

“A marker has been placed at St. Patrick’s Cemetery near my family’s marker stones. That too is prepaid. (The first time I visited the cemetery after my marker’s inclusion, a large white bird dropping lay precisely in the middle of it, a reminder, I suppose, of what lies ahead for me.) There may be some very minor expenses attached to the wake/funeral, perhaps tips or something, but most everything has been covered. Make sure the fellow who laid the stone also places a death date on it. His business in on West Locust, near the Happy Joe’s store. There may be a charge for carving the death date on it, but it shouldn’t be very much.”

Long drag.

That man, Mom says. Always so obsessed with money.

Exhale.

The letter goes on to provide information about his will, his living will, potential debts, and a few minor assets. He calls our attention to two bank accounts, a safety deposit box, and his cell phone carrier. “House keys,” he notes, “are in containers along with everything else on the kitchen counter to the right of the sink. I generally keep a reasonably up-to-date list of phone numbers on top of the refrigerator, and inside my car’s glove compartment. I also have them stored in my computer under ‘Documents/Personal Data/Addresses.’ They are also stored on my cell phone.”

“There may be something more I should add,” he concludes, “but I can’t think what it would be. Just don’t cheer too much until I’m decently out of the way.

“Love, Dad.”

Mom turns to Sara. She says, What are we going to do about that door? And then, holding her cigarette close, she says it again.

Once Bridget and I arrived home to Davenport, the full heat of August bearing down, we conducted an inventory of the condominium—black Hefty garbage bags in hand and Vicks VapoRub smeared under our nostrils. It revealed the following: a beige couch; a twin bed; several side tables, including the one on which the manila folder was found; three bar stools; a small, round, plastic kitchen table and two white plastic chairs; a complete set of golf clubs, circa 1980s, minus a two-wood and a five-iron; a black-and-white Life magazine poster of Martin Luther King Jr., unframed and tacked to the south living-room wall; a cupboard above the dishwasher devoted to plastic drinking cups of various colors and designs, including several green Notre Dame cups, a black-and-gold Iowa Hawkeyes cup, and a circle-C Chicago Cubs cup; a takeout menu for Happy Joe’s pizza attached to the refrigerator by an Iowa State Education Association magnet; a pool cue in faux leather case; a class ring, with inset emerald, Saint Ambrose College, 1962; a gold wedding band; a rented CPAP machine for sleep apnea, with mask; an anti-war picket sign propped up in the west window facing both the street outside and, across the street, an empty lot notorious for being the site of drug deals and shootings; 25 to 30 historical novels, Nero Wolfe books, a coffee table collection of Civil War maps, and a biography of Jackie Robinson; a laminated reproduction Poblacht na hÉireann broadside Scotch-taped to the bedroom wall; a shoebox full of cracked and dirty compact discs, including the Chad Mitchell Trio, the Limeliters, the Kingston Trio, the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem, and the original motion picture soundtrack for 1776; a black duffle bag stuffed with a dozen or more new National Education Association “Peace and Justice Caucus” T-shirts; a dusty 19-inch color television (minus remote control), VCR, and, on a wobbly bookshelf adjacent, a number of video cassettes, including a box set of the full 21-hour miniseries Centennial (1978), adapted from the thousand-odd-page James Michener novel of the same name and starring Richard Chamberlain, Robert Conrad, and the former University of Iowa defensive tackle Alex Karras as Dad’s favorite character, the stolid, humorless, self-righteous, and dependable German Hans Brumbaugh; an album of snapshots and newspaper clippings; several plastic bottles of up-to-date prescription medications, including Dilantin and blood-thinners; a tin containing a few old pennies, a large souvenir coin commemorating the centennial of Delmar, Iowa (1871–1971), and what appears to be a genuine FDR campaign button; a 10-year-old Dell personal computer and ink-jet printer; and, attached to the PC, a thumb drive with the following folders: “Brendan in Korea”; “CF Martin Award,” containing notes for an acceptance speech he gave a few months earlier upon receiving the state union’s highest honor; “Libel Laws”; “Personal Data”; “Photos”; “Political Thoughts”; “Scott County Democrats”; “Seeing Red,” a paper he recently had written about the McCarthy era; “Song Lyrics, American”; “Song Lyrics, Irish”; “Union”; “Wolfe History”; and “Yenta.” This last folder was empty.

In the “Personal Data” folder is a subfolder, “Jokes,” and a Microsoft Word document titled “Four Great Religious Truths”:

1. Muslims do not recognize Jews as God’s Chosen People.

2. Jews do not recognize Jesus as the Messiah.

3. Protestants do not recognize the Pope as the leader of the Christian world.

4. Baptists do not recognize each other at the liquor store.

Another subfolder in “Personal Data” is titled, again, “Yenta,” and inside this one are six Word documents labeled “Novel Café,” one through six. Each contains a list of women’s names, accompanied by short descriptions. “Novel Café #1,” for instance, features 11 names, all printed in a blue Comic Sans font.

6. Marilyn from Davenport. Works at some place between the Kahl Building and Mac’s for nine months, then goes to Arizona and lives in a trailer for three. She’s very good looking and has a bubbly personality. […]

9. Nancy is from East Moline. She is retired from Deere, has no children, is athletic, takes dance lessons. Looks good to me.

10. Karen is from DeWitt. She has been a widow for 2 1/2 years. She has traveled to Germany and Alaska. She is bubbly, outgoing, and I’d like to date her.

Yenta, I later discover, is the Yiddish word for gossip and matchmaker.

Early one morning during the third week of August, in 1993, Mom woke up to find my dad gone from the house, his clothes drawers emptied and a few paperbacks taken from the shelves down in the basement. And on the kitchen table was a scribbled note that contained only his new phone number and the address of an apartment a mile or two away. My parents had been married for 29 years.

Now, nearly two decades later, Mom was sitting at that same kitchen table when I overheard her on the phone with her Congregational minister.

I don’t know, she said. The kids were young.

[…]

No, we never talked about it. Of course not. When he stopped going, then we all did. That was it.

[…]

I don’t know why I didn’t. I—

[…]

Oh, Katherine. You have to understand.

[…]

I know, I know. But you have to understand. He loved God. As a young man, he really did. His family was like mine, traditional Catholics. He used to tell me that we would raise our children in Christ. It’s like he was a different person then. He wanted to adopt because it was Christ-like. Can you believe it? That’s what he said then. Now … I don’t know. I just worry. I worry that he hasn’t gone to a good place.

On his thumb drive I find a Word document called “Reminiscences.” It’s a six-page essay that begins, “My first 17 years were spent on my mother’s farm outside of Delmar, Iowa. Despite the loneliness and sense of isolation I often felt, my experiences there were somewhat enjoyable.” He goes on to mention, without elaboration, that his own father died when he was an infant, after which he describes waking before school to do chores in cold that all but froze the milk inside the family’s Holsteins and Guernseys. He recalls, also without elaboration, “being partially run over by a small building” when he was in high school and, a few years before that, nearly being crushed to death under the right front wheel of a hayrack being pulled along by his neighbor Ray Schmidt’s old F-20 tractor. Then there was the time when he was four—this was 1945, Dad writes, when all available rubber had been donated to the military—and he was riding his steel-wheeled bicycle through the newly planted fields on the morning after a thunderstorm. When he reached out to lift a fallen power line, 120 volts pulsed through his body.

I screamed and screamed until my mother and sisters heard me. Mary Kay, then about fifteen or sixteen, ran to the basement fuse box to turn off the electricity. I have since accused her of taking a cigarette break because it seemed to take forever before I was finally able to release my hand. The damage was considerable. It caused lifelong scars between my thumb and first finger and between my last two fingers. More importantly, it caused neurological damage and gave me epilepsy, something I’ll always have.

“My mother always insisted that I had a guardian angel standing over me,” he writes, “perhaps inattentive for a moment or two, but ultimately saving me from serious harm.”

The neighbor lady first noticed the newspapers piling up on the front porch, then by chance she heard the faint, tinny sound of a television. It was late for him, she told me, and while fumbling for her front-door key—she was returning home, she said, from a night out with her husband—she stopped to listen and then to wonder.

After walking across the grass to Dad’s front window (the same one with the anti-war sign), she raised herself on her tiptoes and peeked through the curtains.

Nowadays I notice, with an editor’s satisfaction, how Dad cared enough to underline (and punctuate correctly) et al.

It was August and he had been there in his recliner, in front of the television, for perhaps as many as four days. As it turns out, the central air-conditioning unit had malfunctioned, which accelerated the decomposition process so that rising gases inside Dad’s abdomen eventually forced his liquefying organs out through the nose and mouth. Or at least that’s how the coroner explained it to me when I inquired about all the blood and effluvium. In a practiced monotone, he said the cause of death was some kind of heart-related event.

I respect people’s privacy, Dad’s neighbor assured me. We were standing in the shade in front of Dad’s condominium. Her freckled arms were crossed as her eyes unconsciously tracked the two young men in blue knit shirts who were hauling garbage bags from the condo and tossing them into the back of a blue truck parked on the street.

Suddenly she pulled from her pocket Dad’s driver’s license, handing it to me. Someone found it in the neighborhood, she said. Your father had his briefcase open on his lap when he died, and all the cards were taken out of his wallet and, you know, neatly stacked up. It was the weirdest thing. It was like he was looking for something and then … he got struck by lightning or something!

She paused. I didn’t say anything.

Anyway, we figure he took a walk—he was always regular about his walks—and, you know, just dropped it somehow.

The DOT mugshot betrayed just enough of a smile that I could see a shimmer of the silver cap on his front tooth—evidence of yet another childhood accident.

I thanked Dad’s neighbor, hoping she might leave, but instead she continued to stand guard, her arms crossed again.

You know, I had an extra set of keys if they would have just asked, she said, referring to the police.

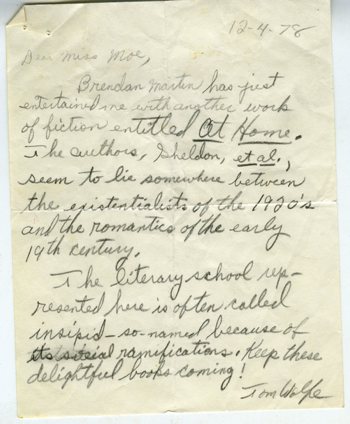

My dad was a prolific and often brilliant writer of letters. His epistolary talent was evident to me even when I was in first grade. I was learning to read then, of course, and my stern, Weeble Wobble-shaped teacher would send me home with a book. My job was to read it aloud and return to school the next day armed with a note attesting to the fact. On December 4, 1978, my dad (who is blessed with a literary name) scribbled the following in pencil:

12-4-78

Dear Miss Moe,

Brendan Martin has just entertained me with another work of fiction entitled At Home. The authors, Sheldon, et al., seem to lie somewhere between the existentialists of the 1920’s and the romantics of the early 19th century.

The literary school represented here is often called insipid—so-named because of its social ramifications. Keep these delightful books coming!

Tom Wolfe

Of course, I could hardly detect any inventiveness in my dad’s note-writing then. But I was able pick up on the flickering looks of surprise and mild disapproval on Miss Moe’s face. Nowadays I notice, with an editor’s satisfaction, how Dad cared enough to underline (and punctuate correctly) et al. Subsequent notes, however, betray a weariness bordering on cynicism.

November 29, 1978

Dear Miss Moe,

My only begotten son, Brendan Martin Wolfe, has just finished reading a breathtaking adventure story involving a boy named Tom (who appears to be wearing eye shadow), his sisters Betty and Susan (who are “sugar and spice and everything nice”), a disgusting canine predator named Flip, a properly supportive mother who wears fluffy dresses, and a masculine father who can fix anything and is actually addressed by his own children as “Father”! (This particular father is often addressed by his youngest child by the very respectful name “Knucklehead.”) All of the above continually wear strangely fixed grins throughout this tale, a fact which leads one to question their intelligence and mental stability. Other delightful characters in this work include Airplane, Pony, Apple, Bunny, and Toys. Not since the writer’s own “Dick and Jane” days has he read anything as exciting yet thoughtful as Odille Ousley’s My Little Red Story Book. One doubts one could survive such excitement again.

Yours in literary wonder,

Tom Wolfe

Three months later, all optimism is gone.

February 7, 1979

Dear Miss Moe,

What precisely do you have against me? I am merely a mild-mannered teacher working in a large metropolitan building. My goal in life is to survive. I hurt no one; yet, my only begotten son, Brendan Martin Wolfe, accosted me immediately upon my arrival home this day and began to yelp the contents of two sterling works, The Case of the Hungry Stranger and Last One In Is a Rotten Egg—the latter being the lad’s autobiography. In self-defense, I’ve had to turn to the grape, and now you’ll have that too on your conscience. You are doing society great harm. Nevertheless, I still remain,

A loving and sensitive parent,

Tom Wolfe

The underlined a, by the way, was a subtle jab against a teacher who stubbornly misspelled my name with an o. Thanks, Dad.

I read the above description of those notes to Miss Moe at Dad’s memorial service, tearlessly and to peals of laughter, in front of a crowd that numbered in the hundreds and consisted mostly of public-school teachers. Remarkably, his own third-grade teacher made an appearance—Dad had just attended her 90th birthday party—while a relative drove all the way down from Ontario. In the receiving line, a man openly wept as he drew nearer to me. All afternoon my cousins had been slipping me glasses of Jamesons, and I threw one back now, concentrating on the lovely way it snaked down my throat. The man looked to be a few years older than me, his graying hair worn heavy metal-band long, his face lined and roughly bearded, his arms inked. With a start I recognized him as Mr. H, my eighth-grade history teacher and one of Dad’s former students. Back when I was in junior high school he had been crew-cut and khaki’d, angrily pounding on the lectern until it cracked. More than once he had hurled chalk at some kid in the back of the room.

I penned a column extolling the virtues of the school newspaper’s adviser. I wrote that he had been the most influential person in my life—after which Dad and I didn’t speak much.

A kid who may have been me.

Your dad saved me, Mr. H sobbed, putting his hand on my shoulder. He picked me up when I was in a bad way. Got me involved in the union, mentored me, gave me some direction. I owe him so much.

I caught one of my cousins’ eyes and, with an appropriate amount of discretion, received another dose of Jamesons. Later Mom grabbed me by the arm and whispered how odd it was, this memorial service.

It’s for them, she said, motioning to the teachers, a boisterous but also insular group. Like firefighters or police officers, they come out for one of their own, offering quick respects to the family before getting back to their tales of classrooms, administrators, union conferences. Among the teachers was my dad’s longtime—in his words—“lady friend,” a warm and maternal presence who, I’m sure, had her own struggles fitting in that day. Mom may have been thinking about her, too, when she said, We knew a different man.

And it’s true. The dad I knew was distant, conflicted, angry, smart, impatient, unforgiving, competitive. He was a man of letters, of words—that’s how we fought. In the ninth grade I wrote an account of the Civil War battle of Shiloh in the style of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about Gettysburg, The Killer Angels. Dad saw it not as pastiche but plagiarism; he saw me not as a budding creative writer who needed to be encouraged, or as a son who yearned to be supported, but as a student who ought to be punished. He advised my teacher to fail me on the paper, and she did.

In high school I edited the student newspaper and wrote a column about standardized tests, suggesting—although this is probably too gentle a word—that our educational system treated us like so many cattle led to the slaughter … or something. I don’t remember the argument so much as I remember that after the local daily newspaper reprinted it on its editorial page. Dad commissioned a scathing rebuttal, which was written by the president of the teachers’ union and printed in the same space.

Some time later I penned a column extolling the virtues of the school newspaper’s adviser. I wrote that he had been the most influential person in my life—after which Dad and I didn’t speak much. In fact, it took him four years to respond and when he finally did so, it was by letter.

I have that letter, and several others, tucked away in a drawer. Pulling it out, I see that it’s typed and dated three-and-a-half months before he left home. “That writing was, I suspect, a catharsis for you,” Dad ventures, “revealing as it did some very deep emotions.”

You mentioned in your writing that your mother was never aware of your senior year “attitude.” Let me assure you that I was very much aware of it! Oh boy, was I aware! Your senior year was the worst year of my life. The only other time that even approached it was Bridget’s last year. (On more than one occasion, I told Sara that I would absolutely kill her if she put me through another year as you two had done. Thankfully, she never did.) Never had I felt so alone, so defeated, so disappointed, so betrayed. Just reading your paper threw me into a 24-hour funk, bringing back memories I have been trying vey hard to suppress.

Although the letter is 20 years old now, I remember this paragraph pretty well because of how it took all of my rage and resentment and just boomeranged it back at me. But it also has stuck with me for the way it provokes the writing teacher in me to pull out a red pen and start marking up the margins:

Tell me more. Why was your son’s senior year the worst year of your life?

What made you feel so alone, so defeated, and so disappointed?

How, specifically, did he betray you?

Consider providing an example of a bad memory your son’s writing brought back.

Under the circumstances, these questions seem awful and condescending—but they are sincere. I really don’t know the answers to them, or, put another way, I suspect that Dad’s answers would have been substantially different from mine. Whatever the case, had I been more generous, I would have better remembered the next paragraph:

I admire you for writing about it and for dealing frankly with some powerful emotions and painful memories. I wish that you and I could be closer—the way we once were, but it’s so hard for me. I’m no good at conversation, and I tend to be so very inhibited at the wrong times.

With four years between the initial exchange, there was no need to rush into further communication on the matter. So we never spoke of it again.

My younger sister Sara’s senior year in high school had, indeed, gone relatively smoothly, and at the time Dad wrote this letter, she was a freshman in college on a full-ride athletic scholarship. A few weeks later, though, she arrived home pregnant and engaged to be married. Dad kicked her out of the house. At first, he refused to participate in the wedding. He finally relented, and the ceremony went off in lovely fashion, although Sara later told me it was strange to her, the way she and her new husband—Sara was adopted, he the product of a mixed marriage—were the only two African Americans in a church full of white people.

I might have wondered then what an odd and atomized family we were, how the electricity that held us tight was beginning to fail, but in those days I thought only about my girlfriend and Guinness.

Then, eight days after the wedding, I received another letter.

“Dear Bridget, Brendan, Sara,” it begins. (A tiny thing, I know, but that missing “and” hints at how nervous Dad must have been at the keyboard that day.)

“Dickens referred to the best of times and the worst of times. Although I wasn’t ready for it at the time, seeing an incredibly beautiful Sara walk down the aisle may prove to have been the best of times. Now I must tell you of the worst.”

He goes on to explain that he and Mom had separated, that this had long been their intention once we were all grown, that this was “easily the most crushing experience” of his life, and that he felt “totally alone.”

There were many causes for our split, but I’m not going to tell you any of them. They are strictly between your mother and me. None of the common causes apply. There was never any physical or verbal abuse, and neither of us has ever played around. Please do not presume to judge or even to reasonably understand the causes of our problems. They go back a long ways, and there is no way you could properly understand them.

He’s gone crazy, Mom told me.

It’s a fucking form letter! Bridget said.

Sara, as is her wont, was forgiving and philosophical. For my part, in addition to succumbing to my predictably thirsty rage, I found myself provoked by the mystery of it all. I was at a loss to understand Dad, and here he was telling me that not only was such a thing impossible, I had better not even try.

Where Dad turned to A Tale of Two Cities, I thought of Edgar Allan Poe’s so-called tales of ratiocination. In stories like “The Purloined Letter,” the protagonist behaves like a proto-Sherlock Holmes, first considering the evidence and then, through observation and hyper-rationality, ascertaining that the truth—in this case a letter—is right in front of his nose. That’s what I thought I could do with Dad—I thought I could figure him out, which is why, at the beginning of my senior year in college, I began to write. I methodically bagged and labeled each part of his and my family’s story, making whatever connections I could and plugging the holes that remained with an elevated sort of self-pity. By the end of the year I had composed a long and clever essay titled, perhaps unsurprisingly, “Letters.” It imagined that insight could be found in illuminated manuscripts such as the Book of Kells, a Latin transcription of the Gospels created by Irish monks more than 1200 years ago. Faced with the abyss of white space in the margins, these scribes of yore began to paint, and soon they were tangling up whole pages in an elaborate, almost suffocating medieval graffiti, labyrinthine curlicues, and complex knot work that caught the eye and then ruthlessly trapped it. My dad and I were like that, I concluded: always trapping one another with words, for years exchanging these letters only, in the end, to circle back to what we didn’t know or wouldn’t reveal. We were the opposite of “illuminated,” and although I realize I’m mixing metaphors here, I longed to be one of Poe’s ratiocinators. I wanted an opportunity to unravel those carefully wrought designs, to straighten them all out, and to finally arrive at some fixed conclusion.

I wanted, in other words, to communicate.

I mailed the essay to Dad but received no response.

Another Word document on his thumb drive: an 11-page essay, titled “Reflections of an Iowa Farm Boy,” that begins by withholding:

In Frank McCourt’s introduction to his wonderful book, Angela’s Ashes, he wrote that nothing could be worse than a miserable Irish Catholic childhood and that a happy childhood was hardly worth discussing. My Irish Catholic childhood was sometimes happy and sometimes sad, but unlike McCourt, I’ll mention only the happy times since I have no desire to tell any part of the world about my private miseries. I’ll leave that to McCourt.

And to me.

Meanwhile, a snapshot from Dad’s photo album reminds me of another passage from that same essay, “Reflections of an Iowa Farm Boy.”

“What I remember most about farm life,” he writes, “was an aching feeling of loneliness. I seldom had anyone to play with, so I learned to use my imagination. Towards dusk of a summer evening, I would ride my bike out to a hay field and climb onto a haystack that had not yet been taken into the barn. There, I would sniff the sweet aroma of freshly mown hay, then stare across the fields into the sky, watching planes go by and imagining life far away. My imagination would soar, and I would yearn for exciting things and places totally unknown to me at that time. Dreams became my constant companion and friend, and still are these many years later. As long as I live, I’ll associate freshly mown hay with those dreams and yearnings, and I won’t know whether to be happy or sad.”

I last saw Dad about three weeks before he died. After attending a national teachers’ union conference in D.C., he and his “lady friend” stopped first in northern Virginia to have dinner with Bridget and then in Charlottesville to visit my wife, Molly, and me. For reasons I don’t fully understand, he and Bridget had been estranged for the last year—he and I, on the other hand, had negotiated an uneasy peace long before—and his meeting with her had left him shaken and upset.

The four of us went out for pizza, and after a few beers I asked him if he had ever met Bridget’s biological mother. (Bridget, like Sara, is adopted.) He said he hadn’t but that he’d always been curious about her.

They kept us all away from each other at the hospital, Dad said, leaning forward on the table. Normally he was terrible at conversation, unable to engage in the simplest small talk, fidgeting, his eyes always wandering. On this night, though, he was red-faced and alert. He sensed from the way Molly and I awkwardly pressed the question and then just as awkwardly retreated from it that we were hiding something.

It’s none of my business, Dad said.

Bridget knows who her real mom is, I blurted out. And then I told him about an email I had received five years earlier from a woman who believed herself to be Bridget’s half-sister. She explained how Bridget’s pregnant, teenaged mother—their mother—had been hidden away in an Iowa hospital for months, forced to wear a wedding ring and to lie about a husband in Vietnam. The man who had arranged this cruel and peculiarly Irish Catholic form of exile was a Father Martin—the same priest, as it happens, for whom I was named.

“Brendan Maaaartin!” Dad liked to say whenever I phoned, rolling his “r” in a poor imitation of an Irish brogue. This time, however, he repeated the name without any relish. An entire lifetime of priests and knuckle-cracking nuns (his aunt, for instance, Sister DePaul, seated in her habit in the foreground of the photograph above) seemed to fill up his eyes.

Back at our house we logged on to Facebook and showed him pictures of Bridget’s biological mother. The similarities between the two were uncanny, from their posture to the fact that they are both nurses. But Bridget had chosen so far not to introduce herself; she and her half-sister had decided the shock might be too great—for all of them, I suppose.

Father Martin set the whole thing up, Dad explained. He considered us to be good Catholics—we were good Catholics—and it helped that I was Irish. Or at least of Irish ancestry.

He paused for effect.

It was my only redeeming quality.

So you didn’t use an agency? Molly asked.

No, no, no, Dad said. Holy Mother the Church. She handled everything.

Molly must have followed up with a question about God—I don’t remember exactly, just that the conversation lingered on religion through another bottle of wine. We discussed the Hebrew Bible, Dad’s refusal to accept the idea of a personal god (always the good social studies teacher, he cited Thomas Jefferson), my own constitutional aversion to churches and synagogues, and Molly’s college reading of Buber’s Ich und Du.

It was a wonderful conversation and like none I had ever had with Dad. During my freshman year in college, he had responded to a letter of mine he described, mischievously, as “patently political.” “You are wading knee-deep in the intellectual whirlpool which exists in any great university,” he wrote, “but you are superbly suited for it. I just pray that you don’t become the supreme smart-ass that I became sometime during my freshman or sophomore year …” He went on to caution me from becoming too ideological, advice I don’t remember receiving but have always followed. What he didn’t do was respond to what I’d actually written. I had always thought that the “intellectual whirlpool” might be a means for Dad and me to connect, but it never quite happened.

At some point I asked Dad why we stopped going to Mass when I was a kid. It happened before I could be confirmed, and I always assumed that some lightning-like moment of theological epiphany had turned him away from Holy Mother the Church, at least in all things save football. As I would soon overhear, his decision so worried my mom, even these many years later, that she despaired of his soul. But, as Dad explained, it wasn’t theology at all that kept him home on Sunday mornings; it was Father Martin. The tyrannical old priest, who had fussily arranged Bridget’s adoption into a family that (ironically) would not tolerate something as sacrilegious as teen pregnancy, had been appalled by my parents’ later adoption, with agency assistance, of an African American child.

(For the record, I am the lone product of my father’s seed. “Never again,” my mother is reported to have said after my birth. “I immediately got fixed,” Dad told me over beers.)

I don’t recall what Father Martin did or said. Whatever it was, it threatened the legitimacy of our family. We were no longer good Irish Catholics, and as a gesture of rebellion, Dad embraced that. I eventually followed his lead without even knowing why. No matter how much it bothers my mom—whose oldest sister was a nun, who also abandoned the church, but who has always held tightly onto God—I refuse to find a congregation. In nomine patris, I find no comfort in it.

About a week later, Dad was back home in Iowa and out listening to Irish music when he texted me: “Am looking right at BC [Bridget Colleen]’s birth mother!! Irish duo performing. Life way way too weird!!”

“Amen to that,” I responded, not sure how to express just how far-fetched the situation seemed to be. I have no reason to doubt it was true, though, especially because of our shared Irish-Catholic heritage. Our whole lives had been lived in the same small city as Bridget’s biological mother and her half-sister; they had shadowed us, like dreams. If only we had known that all along they had been sitting right there, across the bar.

Now we did know, but what should we do?

Dad yearned to approach the woman, he wrote, to announce himself and assert their connection—but I advised against it. Better to let it be, I said, and that’s what he did. However stunned by the coincidence, he let it be. But I’m left to wonder what he was feeling in that moment, or, more precisely, whether he had experienced the same kinds of feelings looking at old photographs of his own father, whether this was how it felt for Bridget to see herself on a stranger’s Facebook page, and whether that was similar to the way in which I carry my dad around with me—the wandering eyes, the sarcasm, the loneliness.

A few nights later, in conversation with my wife, Dad sent one last text: “Goodnight, lovely Molly.”

It was the last time either of us heard from him.

Just as his death letter had instructed, we drove Dad back home to Delmar. I had been there, and to the cemetery on the outskirts of town, dozens of times, but never without Dad sitting next to me, fidgeting and pointing out the turns. We sped north on Highway 61. The way the landscape opens up out there, it’s like the white on an empty page. You can see for miles in every direction—long, low waves of brown-topped corn, the occasional copse of trees—and still feel disoriented. There’s nowhere for your eyes to anchor.

Somehow I managed to get us to Delmar without incident, but I had assumed that from there it would be no problem to find Saint Patrick’s Cemetery. Instead, I turned us around in circles, unable to identify the correct country road. When my cell phone rang, I pulled over at the Catholic church. It was Dad’s “lady friend.” She and some other teachers had arrived at the cemetery a few minutes earlier but were now insisting that it wasn’t the correct place. He took me there not long ago, she said, and showed me his stone. I know this isn’t it.

A few nights later, in conversation with my wife, Dad sent one last text: “Goodnight, lovely Molly.”

I got directions to where she and her comrades had parked and told her to stay put. After I hung up, though, I could barely control my anger. This is my fucking place, not hers, I said, and the obscenity-laced rant that followed ought to have been directed at Dad, not her; certainly not at Molly, Mom, Bridget, and Sara, who patiently dialed me down and maneuvered me back into the rental car. This ground was ours, I wanted to say, not yours. This was the ground on which I could meet my dad—where you can sniff the sweet aroma of freshly mown hay and let your eyes fall across the fields and into the sky.

Where you yearn for things you can’t have and you don’t know whether to be happy or sad.

Dad told Molly all the time he loved me. But I wanted to receive that love in the way that others did. The sobbing Mr. H, for instance, his troubles having been soothed, his life having been saved. Absent that, this is what Dad and I had—Delmar, corn, and a prepaid stone with a large white bird-dropping lying precisely in the middle of it. However selfish and unkind it may have been, I didn’t want his “lady friend” or anyone else to have it, too.

Once I found the cemetery, the same one she had sworn was wrong, I walked directly to his gravesite. Having claimed that small victory, I let go of the day’s anger. In the distance and under an oak, I noticed an old man sitting in a blue Chevy pickup. He climbed out, retrieved a spade from the truck bed, and ambled in my direction, spitting a line of tobacco juice.

All set? he asked, motioning first to my family and then to the freshly dug posthole into which we would drop the bag of ashes.

Think so, I said. The man looked skeptical.

You ain’t got a priest or nothin’? he said, then spit, as if to indicate it didn’t matter either way to him.