Heroes and Villains

Dan Simmons (The Terror) is not only a prolific writer, but his books transverse a multiplicity of genres. His previous opus, The Drood, featured a Charles Dickens charged with defending the reputation of the lost (Arctic) Franklin Expedition from persistent accusations of cannibalism (a story also well handled by Richard Flanagan in Wanting).

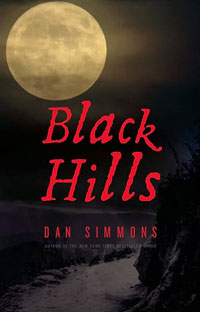

In his newest fictional foray, Black Hills (Little Brown), Simmons creates a Lakota warrior Paha Sapa, which translates as “Black Hills.” The novel’s conceit is that, at the infamous Battle of the Little Big Horn (known until recently in American history books as Custer’s Last Stand), our Sioux protagonist is somehow infected with the soul of the famed Indian murderer, Custer. And if that is not sufficiently unsettling to any reader expecting some variation of Thomas Berger’s riotous historical novel Little Big Man, Paha Sapa is also channeling Crazy Horse and Gutzon Borglum, Mount Rushmore’s sculptor.

Simmons is so accomplished at placing the reader wherever his narrative is set that some of his more improbable gestures are tolerable—a point Barbara Ehrenreich splendidly asserts in her entertaining review of Black Hills:

So what does Simmons need the supernatural for? Couldn’t he be content writing carefully researched historical fiction in beautiful prose? My guess is that he’s using his monsters and ghosts to impress on us that the historical novelist’s business of bringing the dead to life involves a kind of magic.

Ehrenreich also points out:

But for anyone expecting a paean to Native American nobility and spiritual superiority, “Black Hills” holds a surprising twist. Toward the very end, Custer’s ghost, who by this time has had second thoughts about his historical role, points out to Paha Sapa that the Sioux themselves were a “ruthless, relentless invasion machine,” who had beaten back the Arikara, Hidatsa, Mandan, Crows and Pawnee and that the Sioux were, furthermore, ecological vandals: “We could smell your garbage heaps from twenty miles away,” says Custer’s ghost. “The only thing that made you look and seem noble was the fact that you could keep moving, leaving your buffalo-run heaps of rotting carcasses and giant mounds of stinking garbage behind you.”