I do not like picking winners. So you might wonder why I agreed to judge the play-in match for the Tournament of Books—or serve as a judge at all. Any excuse to put off grading 63 student essays sounded nice (and, sure, irresponsible). But then, after I said yes, I learned that all three contenders were dystopian, 300-pagers. I would rather volunteer with a clipboard in Times Square, asking indifferent strangers if they have a minute for the environment, than read 900 pages about the near future. Don’t get me wrong: I care about volunteering for important causes, but lately I’ve been craving straight-up realism and not dystopias eerily approaching our current reality. Do I really need to explain why? (One word, rhymes with “dump.”)

* * *

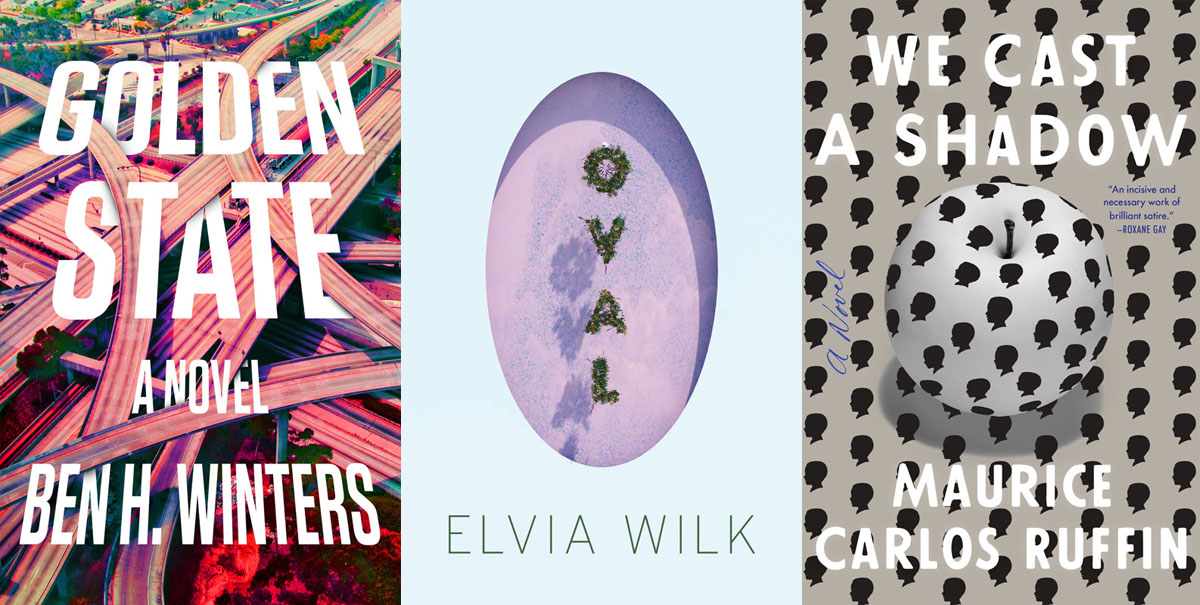

Volunteer work, however, within the hegemony of neoliberalism (stay with me please), is evidence of privatization’s neglect of social programs—at least, that’s what I imagine the two main characters, Anja and Louis, in Elvia Wilk’s Oval would say, given they consider philanthropy a form of money laundering. But Oval is more than an anti-capitalist critique dressed in a fictional narrative that thankfully avoids sounding like it comes from a teenage boy dressed in a Che Guevara shirt. (It critiques parroted critiques of capitalism.) Oval is a near-future dystopian novel exploring love, grief, and the nuanced relationship between empathy and generosity.

Set in Berlin during an affordable housing crisis, it’s told in a close third-person point of view by Anja, a biotech researcher specializing in cartilage architecture, which is not yet a real thing although it (growing cartilage cells to be used as building materials) sounds like it could/will be. Anja’s boyfriend, Louis, is a former artist turned NGO consultant from a working-class family in Indiana. Despite her enormous trust fund, they live in a rent-free, experimental eco-settlement on an artificial mountain engineered by the corporation where she sort of works (corporate relationships seem deliberately hard to figure out). Anja and Louis clearly serve as opposing symbols (rich and poor) of capitalism, but their deepening personal conflicts within themselves and with one another prevent the symbolism from ever seeming reductive or strained.

When we meet Louis, his mother has recently died. His silence about her death bothers Anja, but instead of recognizing that she’s co-opting his grief through her own emotional projections, Anja thinks, “Fuck griefmantra.com and supportcycle.net—there was such a thing as a wrong way to deal with emotions.” Her skepticism causes her to question his behavior, which then leads her to question their relationship—because what does it say about them if he’s not confiding in her? She tries rationalizing his response: “Maybe now he was playing the masculine role because, for once, he thought going through the typical motions might help move him along. Maybe he was so submerged in pain that he could imagine no other recourse for action. But it was also possible that…” And so on. She wants to help, thinks she can help, but her attempts to help aren’t helping.

And this is what the novel gets at on a larger scale with Louis’s character. Around the same time his mother dies, he starts developing Oval, a pill that unlocks (not causes, Louis insists) generosity in its user. Louis believes that capitalism is lodged in the brain but can be temporarily turned off thanks to Oval, which has the capacity to cure income inequality by demonstrating that financial generosity feels amazing. If apolitical creative types with disposable incomes opt for Oval instead of, say, the ecstacy suppositories somebody hands them at a club (you have to read the book), Louis believes it could solve some forms of inequality. How could a Berlin brimming with generous humans not transform into a better place? When Anja challenges his logic, he tells her: “When you start to associate generosity with pleasure, you’ll choose, on your own, to care about the world. Start local, act global.”

I am barely scratching at the complexity of Oval. Just as Louis would like to sneak Oval into Berlin’s club scene, I would like to sneak Oval into every Little Free Library—partly because it’s so good that I want everybody to read it, and partly because I’m interested in how Little Free Library users might critique a Little Free Library after their exposure to Oval. Because you cannot read Oval without then analyzing your every well-meaning action—and then your analysis of your analysis—as it relates to money. What exactly should I do with the hundred bucks that I’m getting for this judgment? Should I donate it to a cause, and if so, which one? And does donating to a cause then relieve our government institutions from doing the work they should be doing? But isn’t it pointless to expect our government institutions—especially under rhymes-with-dump—to enact any sort of meaningful improvements? Though isn’t nihilism what this administration wants from progressives? (I do feel guilty about not wanting to read dystopias because of him.) I suppose this gets at the question behind reading novels such as Oval’s: When does reading a book about empathy translate into tangible change? Or is the reading experience enough?

* * *

Next I turned to Maurice Carlos Ruffin’s We Cast a Shadow. Also set in the near future, it’s told by an unnamed narrator in an unnamed city in the American South. A black employee whose adherence to code-switching keeps him employed at a predominantly white corporate law firm, he repeatedly debases himself among his racist colleagues—all to earn a promotion that will cover a demelanization procedure for his sweet and smart 11-year-old son, Nigel. Nigel is biracial with dark birthmarks that, in the narrator’s mind, expose Nigel’s black heritage and therefore risk his chance at a safe, successful life. The narrator fixates on a birthmark that he believes is darkening and spreading across Nigel’s face: “The birthmark colored from wheat to sienna to umber, the hard hue of my own husk, as if a shard of myself were emerging from him.”

We Cast a Shadow presents a grotesque world that some readers may think implausible, and then the novel shows us why it’s not at all implausible. While demelanization isn’t technically a thing, it seems entirely believable that it could exist given the prevalence of lightening creams sold in our drugstores today. And the fact that the narrator is one of the few black lawyers at his firm also is entirely believable (in 2018, only five percent of US attorneys identified as African American). How does the narrator keep going day to day? Pills. Humor (“I liked my java so black, the police planted evidence on it”). And his desire to give his son a good future. His disappointment in his son, though, is devastating—because on some level, most of us want our parents’ approval. But his acknowledgment that his parental support of demelanization could be viewed as flawed complicates his character just enough—without that self-awareness, I would have lost interest in the plot and in him as a narrator. (It’s hard to maintain a satisfying emotional arc when your main character is so single-mindedly sure that what he’s doing is right.) “I’m perfectly aware of the judgmental thoughts running through your head as you read these words,” he tells us in chapter 16, which details him slathering “super extra strength” lightening cream on Nigel despite Nigel’s protests that it burns. “I have a natural aversion to numbers and statistics, as they can be manipulated by any reactionary with an agenda. But that doesn’t change the objective fact that prospects for African Americans have devolved even since my grandparents’ time.”

His wife, Penny, however, absolutely opposes demelanization, arguing that Nigel should learn to love himself just the way he is; Penny’s whiteness, however, nullifies her opinion, in the narrator’s opinion. While some readers may see her as the voice of reason, the book never shows her talking to Nigel about race in any meaningful way. She also believes that Nigel’s Montessori-like school is a place “where appearances didn’t matter”—even though Nigel, one of six students of color in a school of several hundred, reports being bullied. As a result, the narrator ends up compensating for Penny’s avoidance. A familiar story: The cool parent avoids conflict, casting the other parent as the bad guy.

Like Oval, We Cast a Shadow handles multiple intersecting plot lines by keeping the core focus on love, and it’s the narrator’s relentless love for his son that made me love this novel. It made me feel as much as it made me think.

* * *

As much as I enjoyed Oval and We Cast a Shadow, by the time I reached the third contender, Ben H. Winters’s Golden State, I craved a break from dystopias—which included not reading the news that morning. So I went to the local animal shelter “just to, you know, look,” I told my partner. I give it money every month to curb any impulsive adoptions, but now, there in the cat room, Oval had me thinking about neoliberalism and my monthly SPCA donation and how I’ve felt pressure to increase it after learning that the Baltimore Police Department wants to eliminate its animal abuse unit—even though the unit gets 4,500 calls annually about abused animals. This is all to say: While I tried clearing my brain before cracking open Golden State, I kept thinking about Oval (and yes, I adopted another cat).

Golden State is set in a future state resembling California. Since the rest of the country has been destroyed (presumably) by lies, lies are now punishable by prison or banishment. It’s a perfect premise in this age of “alternative facts” and allegations of “fake news.” Like the best dystopias, Golden State reflects current events and adapts them just enough to terrify us into recognition, and also contains believable characters we can care about (though not necessarily like). Laszlo Ratesic—a grizzled veteran law enforcement officer licensed to speculate when investigating crimes—is a believable character who also seems like a trustworthy narrator. (Speculating to reach the larger truth is a clever reproduction of what Golden State is doing here.) Lies produce a physical reaction in speculators such as Laszlo, and it’s this gut reaction that makes a speculator right for the job: “I felt it way down in my throat, like a clot in a drain.” His brother, Charlie, is considered a heroic speculator who died in the line of duty—and Laszlo, it seems, feels inferior. He’s also feeling bad about his divorce. He’s a loner when we meet him, and the novel leans into this with a familiar storyline: a hardened detective is suddenly assigned an eager new recruit.

Her name is Aysa Paige, and she’s said to possess talents as powerful as Charlie’s. “This girl is my opposite,” Laszlo thinks. “She is short, neat, black, and fully earnest in her countenance. And here I am, this too-big creature, my pale face and my black pinhole, my thin fingers gripping the steering wheel, thick red beard spilling out over the wool of my suit, and my irritation with the world—which is really an irritation with myself—like armor, chain mail rattling across my broad chest.” But he’s flattered that she thinks he’s somebody worth learning from. So he goes along with it.

Laszlo and Aysa’s deepening friendship kept me reading. But I really wish that the emotional backstories—Laszlo’s dissolution of his marriage and his grief for Charlie—had been more thoroughly explored. The conceit is smart and inventive (I haven’t even touched on the “factual” novel within the novel), but the larger plot soon overshadows the human relationships. I wanted fewer clever twists and more character development. Unlike Oval and We Cast a Shadow, Golden State didn’t maintain my interest in the intersecting plot lines—no matter how conceptually interesting. I don’t want to say too much about it, though, because it’s a page-turner that easily could be ruined with spoilers.

* * *

So. I procrastinated on picking a winner by (finally) grading my students’ essays. I then put treats on each copy of Oval and We Cast a Shadow, figuring I’d leave the choice up to my new cat. But that didn’t seem fair. So I asked myself: Which novel made me feel more? And isn’t that the goal of so many writers, regardless of aesthetic: to create emotions? Ultimately, then, I decided on We Cast a Shadow for its range of humor and heartbreak and how it translates arguments—such as there is no whiteness without blackness—into a compelling story rich with sensory description. Oval felt more cerebral, and maybe the third-person narration had something to do with it. But I do keep thinking about Oval.

Thank you to Quail Ridge Books for sponsoring today’s match! Quail Ridge Books is Raleigh, North Carolina’s trusted community bookstore. It’s also the host of the podcast Bookin’ With Jason Jefferies, is the primary sponsor of the North Carolina Book Festival, and is a sponsor of the Hopscotch Music Festival. The store has been a Publishers Weekly Bookseller of the Year, and has been the recipient of both the Haslam Award for Excellence in Bookselling and the Pannell Award for Excellence in Children’s Bookselling.

Upcoming events include David Plouffe on March 7, Therese Anne Fowler on March 10, James McBride on March 17, and Valeria Luiselli on March 19.

Follow Quail Ridge Books on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.

Match Commentary

By Rosecrans Baldwin, Kevin Guilfoile,

John Warner & Andrew Womack

Rosecrans Baldwin: This year marks the Tournament’s 16th year, and 16-year-olds can be pretty assertive communicators, so let’s try this (cue up 16-year-old vocal crackling): WELCOME EVERYBODY TO THE MF-ING TOURNAMENT OF BOOKS OMGGGGGGGGlolllllll 💃💃💃💃💃🌮🌮🌮🌮🌮.

Andrew, do you feel like a 16-year-old? Should we be presenting the Rooster inside a gleaming Snapchat/TikTok cube?

Andrew Womack: [TAKES A DRAG ON A CLOVE CIGARETTE, CONTINUES STARING OUT THE WINDOW AND LISTENING TO THE CURE]

Rosecrans: First of all, shout-out and big ups to our presenting sponsor, Field Notes. They’ve been supporting the Rooster for years, and their notebooks and other products only keep getting better. Do pick up one of their limited-edition 2020 Tournament of Books notebooks, simply because it’s gorgeous! But also because Field Notes is donating all the profits to 826 National, which provides under-resourced students with opportunities to explore their creativity and improve their writing skills.

Andrew: Yes, a huge thank you to Field Notes! And also to all our Sustaining Members. We really can’t say it enough: The Tournament of Books happens because of your support. And not just the Tournament of Books, but also Camp ToB—which will return this summer—and something else we’ll be announcing very, very soon. Please, if you haven’t already, consider becoming a Sustaining Member or making a one-time donation. Now over to you, John and Kevin!

John Warner: Year number 16 of the Tournament of Books. When we started this nonsense we thought we were living through the worst president ever. How young and naive we all were. And here we’ve done everyone the extra favor of kicking off the tourney with a dystopian playoff.

You’re welcome, everyone.

Kevin Guilfoile: Longtime followers of the ToB know that I have a child exactly as old as the Tournament of Books. The boy is driving now, John. The Rooster is all grown up.

While reading We Cast a Shadow (and again while reading Judge Vanasco’s verdict) I kept thinking of the time I lived in Houston when I was in my early 20s. On my second day there, an ad came on the radio for a local night club. They were starting an EDM night (although they probably didn’t call it that in the early ’90s) and the ad went like this:

[Pulsating electronic dance music]

ANNOUNCER: “It’s not a black thing…”

[Pulsating electronic dance music]

ANNOUNCER: “It’s not a gay thing…”

[Pulsating electronic dance music]

ANNOUNCER: “It’s a rave thing…”

People would drop the n-word in all-white rooms more often and more casually than I had ever experienced, and those same people would become dismissive if anyone protested. (Once a guy referred to a Korean person we were working with as a “Chinaman.”) On the way home from work one day, I inadvertently drove my car into the middle of, and thus became a brief participant in, an actual Ku Klux Klan parade, complete with a police escort, white robes (although not that many hoods—they mostly didn’t seem afraid to show their faces), and a giant handmade sign that said, “Thank God for AIDS.”

Were people in Texas more racist than where I had come from? Probably not.

Racism is everywhere, obviously, and I now live in Chicago, which is like the Sistine Chapel of segregation. But there were definitely more outward and shameless expressions of racism down there, and a kind of resignation on the part of most everyone else. We acknowledge that a lot of people who listen to this radio station are giant racist homophobes. That’s OK! Come to our dance party!

John: I’m a northerner who has been south of the Mason-Dixon line since 2002, in South Carolina specifically since 2005, and I find it an ongoing journey to fully understand how race works at a deep level. As tours of historic homes and plantations have sought to be more inclusive of narratives of enslaved people, some of our citizens have complained that such honesty paints their ancestors in a bad light. One of history’s greatest racist monsters looms in bronze over Charleston’s most prominent public square, hundreds of yards from the church where nine people were murdered by a white supremacist terrorist. The statue of John C. Calhoun is on a tall pedestal because when it was lower, it would be routinely vandalized by the city’s black citizens. The racist symbol was placed literally out of reach. The Charleston city council cannot agree on even the most mild corrective criticism on the language describing Calhoun.

Kevin: The examples of racism in We Cast a Shadow might be exaggerated in some cases, but they aren’t all that unfamiliar and, even with its satirical veneer, the humiliation and helplessness in the book feels very real. Its world is one in which there is no real stigma attached to prejudice. People don’t pay a social cost for their bigotry. They can flaunt it. Exploit it. Weaponize it. That is the world our nameless narrator has to navigate. I found it compelling, and also not nearly so absurd as it first seemed.

Shortly after I had finished We Cast a Shadow, but while it was still bumping around pretty good in my head, I was listening to an interview on NPR’s Morning Edition with a woman who was having a difficult time articulating why she was a Trump supporter even though she thought Trump was “stupid” and acknowledged that his policies, like cuts to Medicare and Social Security, hurt her personally. The interviewer, David Greene, pushed her on it gently, and she finally said, “Maybe I’m a racist.” And unlike the dozens and dozens of bewildering and infuriating interviews with Trump supporters I had heard in the previous four years, that one really snapped into focus for me. She didn’t mean that she was voting for Trump with the hope he would promote a bunch of racist policies. She didn’t care about policy, but perhaps she liked Trump because Trump has made it OK for her to say that out loud.

John: I won’t be the first or the last to point out that Trump has revealed what we are as a culture more than he has shaped the culture itself. He even appears to have led this woman to a kind of self-revelation she wouldn’t have recognized previously.

Kevin: A quick word about Golden State. Ben Winters has become one of our best writers of speculative fiction, and this is another strong novel from him. This story set in a society in which lying is outlawed is awfully relevant at a time in which we are bathing in gaslight and official lies from the state. There’s another novel in the bracket that I think was timely in a parallel way. Dexter Palmer’s Mary Toft; or, the Rabbit Queen is a work of historical fiction, but it is, in part, about the ways in which people who should know better can convince themselves to believe—and even evangelize for—a preposterous lie. These are very different novels, but in 2020 I think they would be interesting to read as a pair. I can think of a US senator from your state who ought to give it a try.

John: I’m afraid Lindsey Graham giving a crap about the greater good is a story for a different timeline.

Before parting we should give a shout to Oval, which I don’t think either of us had time to read, but which Judge Vanasco makes sound quite alluring. I’ll be curious to hear from those in the commentariat who gave it a go.

Kevin: With smoke from the starter pistol lingering in the air, John, you and I will be back in the booth on Monday as Micco Caporale will decide between Margaret Atwood’s The Testaments and Suneeta Peres da Costa’s Saudade.

Rooster, take the wheel.

New 2020 Tournament of Books merch is now available at the TMN Store. As a reminder, Sustaining Members receive 50 percent off everything in our store. To find out why we’re asking for your support and how you can become a Sustaining Member, please visit our Membership page. Thank you.

Welcome to the Commentariat

Population: You

To keep our comments section as inclusive as possible for the book-loving public, please follow the guidelines below. We reserve the right to delete inappropriate or abusive comments, such as ad hominem attacks. We ban users who repeatedly post inappropriate comments.

- Criticize ideas, not people. Divisiveness can be a result of debates over things we truly care about; err on the side of being generous. Let’s talk and debate and gnash our book-chewing teeth with love and respect for the Rooster community, judges, authors, commentators, and commenters alike.

- If you’re uninterested in a line of discussion from an individual user, you can privately block them within Disqus to hide their comments (though they’ll still see your posts).

- While it’s not required, you can use the Disqus

tag to hide book details that may spoil the reading experience for others, e.g., “ Dumbledore dies .” - We all feel passionately about fiction, but “you’re an idiot if you loved/hated this book that I hated/loved“ isn't an argument—it’s just rude. Take a breath.