“I am not waiting around to see more light,” says a woman in white linen pants as she walks past me where I am waiting near the front of the line to see James Turrell’s Prado (White) at the Guggenheim. A teenager storms out behind her, then runs back into the room to make sure she has seen everything. She quickly comes back out with her bangled wrists in the air as if to say, “I waited in line for this?” The wait for Prado was more than 45 minutes long.

Bear with me—it’s hard to write about Turrell’s work without reverting to acid trip clichés.

I knew the trick to Prado going in because I’d seen a sister piece at the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh. I knew when you enter the dark, white-walled room of Danaë at the Mattress Factory, you see a glowing rectangle on the far wall. As your eyes adjust, you can’t tell if it’s a TV monitor, a projection, or a painting. You’re expected to stop in the middle of the room and then slowly work your way closer to the rectangle. As you grow more comfortable with the darkness, you suddenly realize that it’s not a physical object, but a hollow space illuminated with a bright violet light. You try to find the exact point where the rectangle stops looking three-dimensional. When you aren’t able to, your mind resets. If it works correctly, you ask yourself: What else is my mind projecting onto reality?

At the Guggenheim, you aren’t allowed to take enough time or get close enough to Prado for your perception to change on its own. Each piece on display is tended by a uniformed guard who observes, and at times, limits your interaction. So instead of letting your mind leap from physical space to light on its own, a guard breaks the illusion by jabbing her hand into the rectangle of light. Instead of having a powerful realization about the limits of your own perception, you feel like M. Night Shyamalan propped the guard there.

I could say that James Turrell once pointed at me and told others to follow my example. But in that crowd of Carnegie Mellon art kids, he may as well have called me milquetoast.

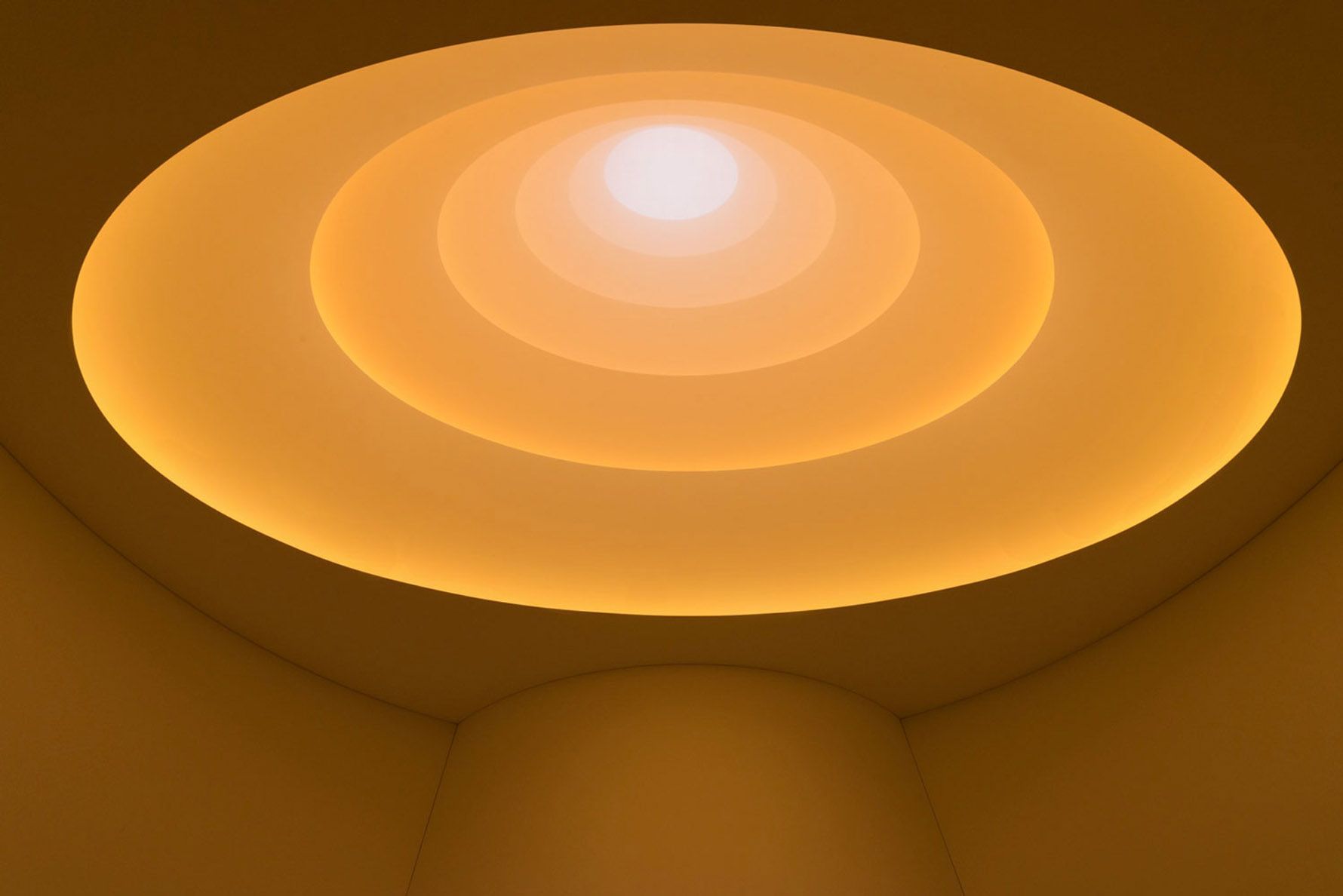

It never occurred to me that there would be a line for Turrell at the Guggenheim. Compared to the line hype about cronuts and the Rain Room exhibit at MOMA, the press about Turrell was muted. But an obligatory New York Times Magazine piece and a flood of Instagrams of the Guggenheim atrium bathed in fluorescents from people who disobeyed the “no pictures” policy, were enough to encourage many people to wait in a 45-minute line.

I have a few theories why people walked out of Prado angry. When someone hears about the Guggenheim exhibit, they hear about the 79-foot tower spectacle of Aten Reign—his largest piece to date—and the rest of the pieces are an aside. Because critics often use violent action words to describe his engineered experiences—exploded, invasive, oppressive, rewired—it could be surprising to find an understated piece. It’s also possible that even with nonsense vocabulary, it’s still hard to write about Turrell and space and light.

Either way, I was used to being alone with Turrell.

The summer after I graduated from college, I had an internship at the Mattress Factory, on Pittsburgh’s North Side. The museum was named, practically, because the building had once been a Stearns & Foster mattress warehouse. The museum once showed Ann Hamilton, John Cage, and Kusama and seemed perfectly out of place in the then-shambles of the North Side. I identified too much with the museum. I had lived in Pittsburgh my whole life and felt like an oddity but believed that the city was better off because of my presence. It was impossible to decide if I loved or loathed the city, but I felt a pull to run away from the place where my grandmother was born and where my father was dying.

With the abysmal post-9/11 job market and a degree in creative writing, it was harder to leave than I imagined. I tried to make something of my summer in between the shifts at Starbucks that helped me make rent. That was the same summer that James Turrell was installing his year-long Into the Light exhibit to mark the museum’s 25th anniversary.

I was too spoiled to fully appreciate how novel it was to toil in the same oxygen as Turrell. I’d been going to the Mattress Factory for years and had taken his permanent installations there for granted. They felt like a natural part of the city’s faded grandeur, like the Heinz factory that no longer made ketchup.

I interned in the development/communications department, primarily working in FileMaker Pro on a “vintage” Mac or writing brochure copy. Sometimes, I got to hang around the lobby when Turrell, looking like Walt Whitman would have looked if Whitman had written poems about the Arizona desert, was giving directions to the exhibition staff. On lucky days, I got to work with the exhibition interns—who whispered hopeless schemes of scoring an invitation to Turrell’s secret Roden Crater project—and cut foam core for exhibit signs. I became pretty handy with an X-Acto knife.

If part of the transcendence of installation art is to interact, how does it change your experience when most of the interaction is in the line and mediated by guards?

Part of my job was to help get press coverage for the exhibit. My boss (Sarah? Susan? Emily?) grumbled constantly about the New York Times. The Times should be paying attention to us. Why aren’t they writing about us? We’re as good as the Whitney. This is James Fucking Turrell.

Sculpture Magazine and the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette covered the show. The Times never called.

As the summer wound down, I didn’t know what I was still doing in Pittsburgh. All of my friends had moved on to cities with actual public transportation, and I was subletting an apartment from a friend of a friend. If I was being slightly honest with myself, I had just read Mysteries of Pittsburgh and I was looking for similar distractions while I was waiting for the job market to get better. If I was being honest with myself, I was playing chicken with an on-again, off-again boyfriend. If I was being really honest with myself, I was scared that I would never understand the marrow of another city.

A few days before the exhibit opened, because nothing else was clean as I was getting ready to go to work, I put on a pair of Starbucks-shift-appropriate wide-leg khakis. Turrell huddled everyone up, dressed in his standard black jeans and black T-shirt, a stark contrast to his white beard. When he spoke, we hushed each other.

In the lobby was the centerpiece of the show, a gray sphere that could’ve been a set piece on 2001: A Space Odyssey, or maybe part of the wreckage of a steel factory. It was part of his perceptual cell series, called the Gasworks. A small pull-out bed, something you might see in a morgue, carried you into the belly of the sphere. It felt like being inside a wormhole. Warm patterns of light consumed your entire field of vision, until someone pulled you out, plopping you back into a world that was significantly less colorful.

I wish everyone who waited in line at the Guggenheim could instead happen upon Prado at the end of a meandering dark hallway.

In the huddle, Turrell explained that the staffers who operated the Gasworks should imagine themselves as technicians administering an MRI. Be clinical. Don’t upstage the art.

“Don’t dress in anything distracting. Nothing with holes. Try to look clean and professional,” he said. He scanned the crowd of thrift T-shirts and Sauconys and eventually pointed at my khakis. “Like her.”

I could say that I was singled out by a genius. I could say that James Turrell once pointed at me and told others to follow my example. But in that crowd of Carnegie Mellon art kids, clean was the worst thing you could be. He may as well have called me milquetoast.

I’m not the girl Turrell saw in those pants. I’m contrarian to a fault. Popular opinion makes me nervous. Which is why I’ve never understood the attraction to a line. Lines make me feel like I am a steer that needs to be, well, steered. Lines remind me that I am waiting for something that everyone else is waiting for. There are people who will wait in line for four hours for a cronut and still recommend the experience, but to me a line connotes that whatever is at the end will never be worth it. Lines bankrupt the ending.

Standing in line at the Guggenheim for Turrell went against my nature. But then again, I knew what I was getting into.

“Red carpet” installations like the one at the Guggenheim are a development department’s dream, and they give an artist like Turrell, who hasn’t had a show in a “big museum” since the ‘80s, well-deserved exposure. It’s something we would have killed for at the Mattress Factory. But it seems like there’s a point at which a line breaks the experience. If part of the transcendence of installation art is to interact, how does it change your experience when most of the interaction is in the line and mediated by the guards? Just in terms of logistics and energy, when does the experience upstage the art?

The Times profile that Sarah/Susan/Emily at the Mattress Factory would’ve killed for had a key quote: “The joke among Turrell’s friends is that, to see his work, you must first become hopelessly lost.”

It’s easy to get lost in the Mattress Factory. The floor plans are rambling—much like the streets of Pittsburgh. The museum can feel like an abandoned funhouse. The second floor, where three permanent Turrell pieces are on display, is dark and hushed. It’s easy to find yourself inside one of his pieces by accident. The piece can start changing your perception before you can even get your bearings or figure how you ended up there.

When I had to go hunt through the funhouse for a staff member working on another floor, it was often like a sprawling game of Marco Polo. After a few Marcos and Polos, I loved finding someone hanging a sign or fiddling with the projector, destroying the cathedral-like atmosphere.

Waiting in line is another way to destroy the cathedral, but while seeing the bones of a piece of art can add another dimension to your perception of it, hype often tells you what you should see, like a guard waving her hand in front of a light.

I wish everyone who waited in line at the Guggenheim could instead happen upon Prado at the end of a meandering dark hallway.

My favorite piece at the Mattress Factory is Catso, Red (though I always remember it as Castro, Red). It also has a sister piece at the Guggenheim, called Afrum I (White). They share the same concept: a shape projected into a corner of a dark room, which the viewer sees both as a light wrapping around a corner and as a floating, touchable box. At the Guggenheim, the temperature of the light is, again, more rigid. The red in Catso/Castro seems caught between its two forms, and more flexible between shifts in perception than the dull white in Afrum.

During my breaks, I would sit on the floor of Catso/Castro and think about all the decisions I was avoiding during the rest of the day. I knew that although the light looked like it was transforming, without my brain, it was just a projector pointed into a corner. I was the one who was shifting.