Recently, while flipping through the channels on my mother’s fancy new big-screen television, I come across Nancy Grace.

Nancy is playing bits of audiotape from Mel Gibson’s phone rant to his ex-girlfriend. I find myself strangely fascinated by Nancy, the former prosecutor-turned-talk show host. I can’t figure out why her guests keep coming back. One minute she’s a humble but proud mother of twin toddlers, deflecting compliments from callers who claim she’s “an angel, sent to earth to help those victims who can’t help themselves”; the next, she’s a loud-mouth, impetuous bully, cutting off her guest lawyers mid-sentence with comments like, “Wah wah! Go home and cry to mommy, why don’t you?”

Nancy is about to lay into Atlanta Defense Attorney Raymond Judichey when my mother walks into the room. Setting a large bowl of popcorn on the coffee table, she makes herself comfortable on the couch adjacent to my recliner.

I’m in town visiting for a few days, long enough so the two of us can catch up, but not so long that I’ll consider legally emancipating myself and she’ll end up cutting me out of her will, leaving everything to my sister. As children, my sister and I would fight over who would get our mother’s “Casablanca Video Membership” card when she died. Even though the business has long since closed, my competitive nature keeps me motivated.

“What are we watching?” she asks.

Tension fills the room. Having lived with the woman for eighteen years, I know how she feels about programs pertaining to violence, profanity and/or sexually explicit material. Generally, if there aren’t contestants screaming “No deal!”, my mother doesn’t want any part of it.

“It’s Nancy Grace,” I tell her. I add the part about Nancy being an advocate for victims’ rights, so my mother doesn’t judge this woman who is now referring to Mr. Judichey as “a bloody idiot.”

Why doesn’t she go back to her room and play Solitaire, or Bejeweled Blitz, or any other online game she plays? Instead she just sits there. The longer she stays silent the more I cringe every time another word is bleeped out. I would change the channel, but that would only make her suspicious. What is it that you don’t want me to see, exactly? Only thing I can really do is act oblivious and wait for the sermon.

“I can’t help it. In fact, sometimes I feel so sorry for your generation that I cry myself to sleep at night.”

“I feel sorry for your generation,” she says.

“Why do you feel sorry for my generation?” I say. “Mel Gibson is your age.”

“You know what I mean.” She grabs a handful of popcorn, dropping the kernels on a tissue placed neatly on her lap. “This is exactly the reason why you and your sister aren’t married.”

I try to keep an open-mind, but what she’s not making sense. “You’re right, mom. The only reason we’re not married is because we’re scared that Mel Gibson will show up during our wedding and start verbally attacking us.”

She tells me not to be smart. I assure her that’s not what I was trying to be. I contemplate adding that I’m worried she may be suffering from early-onset Alzheimer’s Disease. I keep the best interests of her video card in mind, bite my tongue, and reach for the popcorn instead.

Back when videocassette recorders were considered innovative technology, my mother brought home the movie Mommie Dearest. Based on the 1978 novel, the film was based on the life of screen actress Joan Crawford, as told by her adopted daughter Christina—who, along with her brother Christopher, was physically and mentally abused by the Hollywood star.

Every so often, my mother would get up and press the Pause button on the VCR to point out Joan Crawford’s lack of proper parenting skills. “Did you see that?” she’d say, rewinding the tape to where a crazy woman with painted-on eyebrows was yelling at her petrified, cowering daughter. “You girls should be thanking your lucky stars that your Mother isn’t like that.”

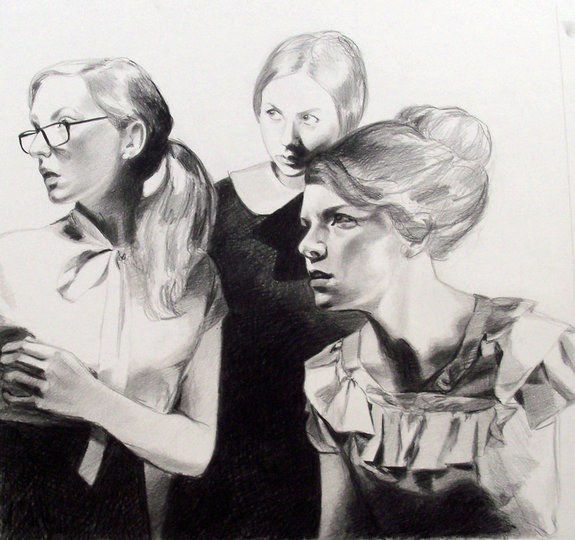

She was trying to prove a point. But rather than feel relieved that she didn’t try to beat me in swimming races, like Joan Crawford did her daughter, or chop off my hair for rifling through her Mary Kay products while searching for a shade of rouge to match my burgundy velour jumpsuit, I spent the entire time we watched the movie fixated on Christina. The way her long eyelashes fluttered when she blinked, and how perectly her little nose would crinkle every time her mom threatened to teach her a lesson. I wanted to be her. Even if it did mean having a hot mess for a mother.

Other neighborhood kids spent their time riding bicycles with straw-covered spokes and handlebar tassels up and down the street, and I’d be sitting cross-legged in front of the television, committing Christina’s mannerisms to heart. “Yes, Mommie Dearest, ah reckon ah am gettin’ too big for mah britches,” I’d say, trying to look adorably somber, wearing my “I Hate Mondays” sweatshirt.

After three minutes of labor, I would flop down on my bed, physically and emotionally spent, wondering why God had sent me to live with such a monster.

Since my parents drew the line at buying me a ruffled pinafore dress and matching bonnet, I had to make do with a Kiss the Cook apron and my mother’s old rubber swimming cap, complete with yellow dandelions picked from the lawn and Scotch-taped to the crown.

“PUH-LEESE MOMMY DEAREST!” I’d say, falling dramatically to my knees and clutching my chest when my cruel tyrant of a mother told me to clean my bedroom. “Ah’ll do whatever yew say! Just don’t make me git the axe!”

Using my sister’s toothbrush, I would violently scrub a two-inch section of my carpet floor with as much intensity as I could muster. Then, after three minutes of labor, I would flop down on my bed, physically and emotionally spent, and thumb through the latest issue of Tiger Beat, wondering why God had sent me to live with such a monster.

After a babysitter told my Dad I’d complained of a headache because “Mommy beat me over the head with a wire hanger,” my Mother confiscated the video and warned me that if I didn’t can the abused-child shtick I’d be grounded until I was old enough to have my own delusional children.

The fact it’s now 20 years later and still these delusional children have yet to materialize, is something that I know weighs heavily on her mind.

“When I was young, they had wholesome family shows like The Waltons and The Brady Bunch and Shirley Temple movies,” she says. “Now every time you turn on the television all you see are celebrity couples fighting and threatening each other. That’s why you and your sister are scared to commit, because you watch these programs and think the same thing will happen to you.”

“Domestic abuse isn’t a by-product of the paparazzi, mom. There was just as much violence going on in the old days as there is now. The only reason you didn’t hear about it back then was because nobody ever said anything. It was all done behind closed doors.”

Sighing, she pulls out a toothpick from her robe pocket and starts dislodging popcorn kernels from her teeth. I know I should leave it there, but I feel like I’m on a roll.

“In fact, it was probably worse in the old days because women were considered the inferior sex. So, even if your husband was a total jerk, it’s not like you could do anything anyway because you’d be ostracized from the community and sent to live in a cave.”

I don’t know if the last part is true, but I remember hearing something about women and caves in high school. Besides, I feel like it really drives my point home.

“Still,” she says, “I feel sorry for your generation.”

“Well, then I feel sorry for your generation.”

“This isn’t a contest, Ruby.”

She calls me Ruby because I’m her gem, she says. I find it ironic I only ever hear it when she’s using her condescending voice.

“I know it’s not,” I say. “I’m just stating a fact. I really do feel sorry for you guys.”

“Well, you shouldn’t.”

“I can’t help it. In fact, sometimes I feel so sorry for your generation that I cry myself to sleep at night.”

I pretend to wipe a tear from my eye, fully aware I’m now being an asshole.

“Change the channel,” she says. “I want to watch Deal or No Deal.”

Defeated, I hand her the remote. I say, “I also feel sorry for your generation because you watch shows like Deal or No Deal.”

Looks like my sister will be getting the video card, after all.