Kevin: So, John, for the first time in more than three decades, the Pulitzer board refused to give an award for fiction this year.

As a pair of individuals who have been fairly immersed in the celebrated fiction of 2011, how are we supposed to feel about that? Intentional or not, it’s undeniably a statement about something. But reading all the mass-produced hullabaloo over the last few days, it seems like readers are as unable to agree about what it means as the Pulitzer Board was unable to agree about what a good book is.

Let’s deconstruct the process.

A committee made up of three people—Susan Larson, a former newspaper books editor; Maureen Corrigan, NPR book critic; and Michael Cunningham, novelist and owner of actual Pulitzer hardware—were assigned to send nominations to the board. So far, so good. They came up with three books: Denis Johnson’s Train Dreams, Karen Russell’s Swamplandia!, and David Foster Wallace’s The Pale King.

So let’s stop there for a minute. I’ve read Swamplandia! and The Pale King and I enjoyed them both a lot. I haven’t read Train Dreams yet, but I’ve loved everything else I’ve ever read by Johnson. Maureen Corrigan says in The Washington Post that these books were the “unanimous” selection of the three jurors—but it seems unlikely that all three jurors thought these were the three best books of last year. There was some discussion and compromise, right? At the Rooster, we have been going on and on about the arbitrary nature of these things for eight years—three different people on a different nominating committee almost certainly would have generated three completely different novels.

So they pass these books on to a 20 member board. That’s a lot of board to be deciding on the past year’s best work of fiction. Not to keep patting ourselves on the back, but that was kind of the joke that launched the Tournament of Books. I imagine getting a consensus about art among any 20 people is difficult. And I very much doubt the Bronte sisters ever agreed what the best book was in any given year.

Now let’s look at the makeup of the board. Perhaps not surprisingly it is made up of 19 newspaper editors and journalism professors and (OK, perhaps a little surprisingly) 2008 Pulitzer winner Junot Diaz, who sticks out on this list like the Short Circuit robot in a Whit Stillman film.

The winner of the Pulitzer Prize, or any other award, is not the “best novel ever” or even necessarily the “best novel of the year.” Its binding doesn’t cut glass or leave gold skid marks when you drag it across a coffee table.

I think if you take a hard look at this list of people you will realize the significance of the Pulitzer Board refusing to give an award for fiction this year—to the newspaper and academic folks, if not everyone else, the prize for fiction is an afterthought. It’s the undercard.

In fact, there might have been some integrity involved in the decision. Everyone feels bad that David Foster Wallace was insufficiently medaled in his lifetime, but almost nobody thinks The Pale King is his finest work, or even a completed work of fiction. And I can see 20 people having a difficult time reaching a consensus over Swamplandia! and Train Dreams. John, you didn’t really like Swamplandia! either. In fact there was a lot about it that drove you a lot crazy.

But the statement made by refusing to award any of the books forwarded to them by the committee is that no novel published in 2011 is up to the standard set by the Pulitzer Prize in over 60 years of arbitrary award giving. And that’s nonsense.

The winner of the Pulitzer Prize, or any other award, is not the “best novel ever” or even necessarily the “best novel of the year.” Its binding doesn’t cut glass or leave gold skid marks when you drag it across a coffee table. There were no doubt a hundred novels published in 2011 that were “good enough” to win the Pulitzer, and to not pick one, for whatever reason, seems not only arrogant, but ignorant. At some point, after the board’s deliberations seemed to be turning south, somebody should have interrupted and said, Come on people, get serious.

By making the de facto statement that no work of fiction last year deserved their award, they almost seem to want to undermine whatever credibility they have to award it in the first place.

John: I have seen two major awards in person, the Heisman Trophy and the Pulitzer Prize.

The Heisman was in the home of one of my childhood friends and longtime hockey defensive partner, whose father won the award in 1967, being chosen over a certain USC running back named O.J. Simpson who would win the next year. They were not the type of family to make a big deal of such things, and I saw it by accident, during a sleepover when I made a wrong turn for the bathroom, and wound up in a spare room where it rested on a shelf. I didn’t linger because that seemed rude, but it was cool.

The Pulitzer Prize I saw belonged to Robert Olen Butler. It was small, crystal, paperweight-sized, classy-looking. I’m pretty sure it was on a side table in his home, though to be honest it’s been 16-17 years and I don’t have a firm memory of the specifics.

Let me also just note that the report of the three-person jury reading “about 300 novels each over the course of six months” is, of course, ludicrous.

What I do remember is that it meant something, a lot of different somethings actually.

For Bob, it’s meant a lifelong career. Bob won the prize in 1993 for his collection of short stories, A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain, which I read when it came out because he’d come to my undergraduate alma mater for a reading and stunned the audience with the title story, in which a dying man is visited by Ho Chi Minh who is covered in confectioners sugar because it turns out that Ho Chi Minh is a baker. Having heard that story, which felt like a kind of magic in that auditorium, I felt compelled to read the rest of the collection. At the time, Bob had already published six well-reviewed, but not tremendous-selling novels, the kind of mid-list career that used to be pretty common, but is increasingly being squeezed out of existence by the economics of publishing. I think winning the prize essentially meant that he would no longer have to worry about whether or not his next book would get published, though given his dedication to writing, it’s possible that he never worried about this anyway.

I chose McNeese St., where Bob was teaching at the time, for many reasons: the interesting nature of the place (Southwest Louisiana), the quality of the students already in the program, that it was for three years instead of two, the low cost of living, the cheap beer and billiards available at any number of local establishments, and yes, also because of that feeling I got when I heard Bob read “A Good Scent….”

The Pulitzer Prize didn’t really matter to me, but it did matter to other people. Every time someone asked me where I was going to school, and what I would be studying, I could say I was studying with a Pulitzer Prize winning author, and that was the end of that discussion because everyone knew that meant something.

There’s probably a dozen or more other books that you and I aren’t even aware of that could’ve made the grade, kind of like A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain in 1993, or Paul Harding’s Tinkers in 2010, which couldn’t have sold more than 1000 copies before its surprise selection.

Do I quibble with the trio of finalists that the jury put forward? I do. I do quibble, but I would quibble with just about any trio of finalists. While I think Swamplandia! is charming, but deeply flawed, and the inclusion of The Pale King is kind of like the push to get Martin Scorsese his Best Director Oscar for The Departed, it’s Train Dreams that is the sorest thumb. It’s a novella. It was published in almost identical form in The Paris Review in 2003. That doesn’t feel like the best full-length fiction of the year, no matter how good it is.

If there’s blame, it probably belongs with the system of choosing requiring a majority vote of the board. When you have to find a majority from a selection of three, you’re asking for it. I’m surprised the no-award decision doesn’t happen more often. Imagine the Tournament of Books if our Zombie advanced not to a special head-to-head round, but to a three-way competition in the finals. I can only think of one or two years where one of the books would have had a majority.

And before passing it back to you, Kevin, let me also just note that the report that the three-person jury “read about 300 novels each over the course of six months” is, of course, ludicrous. This would require reading almost two books a day, seven days a week, for those entire six months while also being, at least in the case of Maureen Corrigan, a professor of English at Georgetown. Bullshit. No one is capable of this, not if they have jobs, lives, or engage in basic personal hygiene. I’m willing to grant that the jury “considered” or maybe “reviewed” or “sampled” that many books, but “read”? Not a chance.

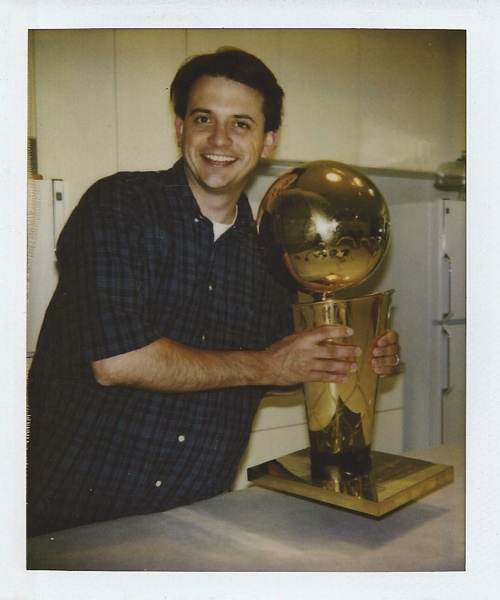

Kevin: I used to collect pictures of me with other people’s trophies. For example, one of me and a Bulls NBA Championship trophy. I don’t know which trophy it is—the Bulls have so many—and how we got it into what appears to be the kitchen of a house I once shared with a Chicago funk band is a memory lost to a pitcher of El Jardin margaritas. I trust it was safely returned.

The Baseball Hall of Fame used to have a thing called the Veterans Committee. It was a panel of old players and executives and sports writers, and they used to get together in a room each year and argue over which old-timers deserved to be in the Hall of Fame. Different individuals would make their case and they would vote and revote, like a jury. Usually they would come out of the process with a name.

Then about 10 years ago they changed the rules so that instead of a committee, the living Hall of Famers would each get a ballot and they would just mail their vote in. No meeting. No arguing. No compromising. And guess what? They never elected anybody.

So to their great credit they tweaked the process again, and that’s the story of how nine-time All-Star Ron Santo was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame about three minutes after he died.

Whatever the reason this happened, I hope the Pulitzer folk realize that the system here is broken. At a startling moment when one of only two novelists on TIME’s list of the 100 Most Influential People in the World is a writer of naughty Twilight fan fiction, we don’t need the Pulitzer saying that nobody writes good books anymore.

Literature needs champions. Be one.

John: The Downtown Athletic Club doesn’t decide to cancel the Heisman when the best they can do is Gino Torretta or Eric Crouch. They don’t call off the BCS Championship if the best teams have one loss. For better or worse, the Pulitzer is literature’s national championship, and it just feels dumb and miserly to deny the pleasure of arguing or cheering or scratching our heads over the choice.

At Bookslut, Jessa Crispin, someone who I rarely disagree with, called the decision “ballsy,” but that pre-supposes that the reason the jurors didn’t chose a winner was because they found the choices wanting.

In 1974, Thomas Pynchon was denied the prize for Gravity’s Rainbow after the voters rejected the jury’s unanimous recommendation. That was ballsy, or to my mind stupid, but it actually made a statement about literature.

The statement this time, I fear, is that they just couldn’t agree when presented with a list, and probably hadn’t read enough fiction from the last year to substitute a title from their own judgment. I guess it’s ballsy to decide you know enough about the state of the year’s fiction that you haven’t read to deny the awarding of the country’s most prestigious prize, but I can think of some better words for it.

Our friend at Book Riot, Jeff O’Neal, said that he likes the pot-stirring quality of the decision, and to wake you and I from our off-season slumber to chit-chat over books is a pretty mean feat, but the takeaway for the average reader (or non-reader) is that nothing was good enough to merit a prize, and I don’t think that takes us anywhere good.