Aliens in the Land of Egypt

For Americans, invitations to Israel—with lavish parties, higher education, and United Airlines tote bags—come easy. But if your homeland lies elsewhere, Israel’s welcome is far less loving.

Nothing is guaranteed to make an American abroad reflect on home more than a proper Fourth of July with burgers, ice cream, fireworks, bunting, Shimon Peres, and the Middle Eastern version of the Miller Girls. I moved to Israel over a year ago, hoping to escape the daily slog, and I’ve largely succeeded, displacing post-college ennui with vegetable shopping, grammar exercises, and road trips to Jordan. I’ve also seriously upgraded my social life, replacing a Fourth of July beer on the fire escape with an invite to the U.S. ambassador’s personal party.

I’m not the only person with the bright idea that maybe Israel could provide a better future. That’s Israel’s promise to the world: to be a place where Jews (and half-Jews and quarter-Jews) feeling beaten down by a bad economy, oppressive political system, or stagnant love life can settle and, in short order, have all their problems solved.

The problem is that the offer isn’t too good to be true, and now Israel has a long-simmering problem reaching a boil: the “infiltrators.” Since the mid-2000s, over 50,000 African migrants have crossed from Egypt, through the Sinai desert, to end up in the outskirts of Tel Aviv.

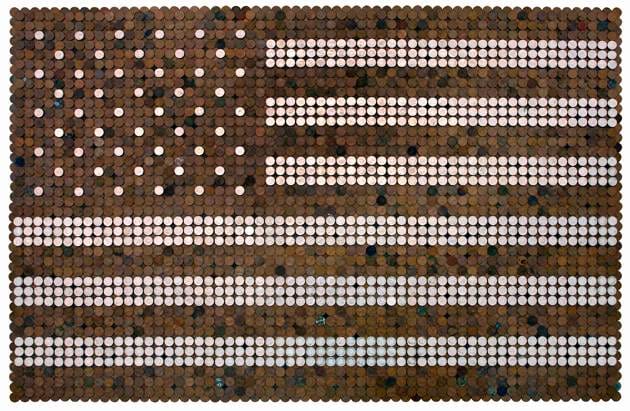

On the Fourth of July we celebrate America as an immigrant melting pot, built on the backs of men and women who said, “Forget you!” to their country of birth. People who showed up in a new place, decided they liked it, and claimed it for their own, largely disregarding pesky things like borders, citizenship, and governmental authority.

The irony of a nation built by refugees deporting planeloads of Sudanese asylum-seekers has not been entirely lost. Leviticus 19:34 makes frequent appearances on newspaper op-ed pages.

Infiltrators—mistanenim. That is the Hebrew term of choice for illegal immigrants. Please don’t think the Israelis don’t know how awful that word choice sounds in English; they do.

Israel’s position in the Middle East used to be defined by fast wars with neighboring states and slow-burning internal conflict with the Palestinians. For the past 10 years, though, things have been quiet. A little bump in the road with Lebanon, with Gaza, a new government here or there, but in general, smooth sailing. At the same time, things have been going to pieces in the Horn of Africa. Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, both Sudans: None of these places are really ringing in the 21st century in style

For years now, there has been a small but steady inflow of African migrants to Israel. Most make their way up to Egypt, then put themselves in the hands of Bedouin smugglers to get across the Sinai. Pretty much the last place you want to find yourself in the world is in the middle of a desert, cashless, waterless, and in the hands of a smuggler. Terrible, terrible things happen in the desert, but enough migrants make it through to Israel to keep the enterprise alive.

I see these migrants all over Tel Aviv. They’re not difficult to spot: young men in dated clothes, sleeping on park benches, chatting in groups on the street, the lucky ones working in the back of a restaurant and the unlucky ones picking up bottles for cash.

The parallel to illegal immigration in the U.S. would hit even the densest Minuteman over the head. Here, too, there’s talk of a big fence to keep out would-be crossers. Politicians use them as a scapegoat for all of society’s ills, claiming they bring with them crime, disease, the obesity epidemic, rising phone bills, and bad reality TV. Many apply for asylum or refugee status, and few get it. College students take up their cause but drop it as soon as exam time comes around.

However, a few weeks ago Israel did what no American administration has ever dared to do: massive deportations. The Israeli government has started flying planeloads of South Sudanese back home. You can practically hear Fox News clapping with trans-Atlantic glee.

Of course, the irony of a nation built by refugees deporting planeloads of Sudanese asylum-seekers has not been entirely lost. Leviticus 19:34 makes frequent appearances on newspaper op-ed pages with its call to “love the alien as yourself, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt.”

And here is where our stories begin to cross. The Jews left Egypt, wandered in the desert for 40 years, knocked down the walls of Jericho, saw their fortunes wax and wane, but have finally arrived. Arrived, that is, at the ambassador’s party, in nice cars, the men in linen shirts, the women in high heels, both chatting about their brother’s new Android app. This party had the country’s best and brightest, meaning predominately Ashkenazi Jews.

It was a fancy party with an old-fashioned receiving line hundreds of people long. There was full TSA security, with metal detectors, wands, and chemical swabs. The party was in the garden and featured Cinnabon, Ben and Jerry’s, Domino’s, and a full-size McDonald’s teleported in straight from a New Jersey food court to Eretz Israel. Carnival Cruise ran the bar, while Jack Daniels and Miller had separate stands each. The guests were an equally diverse bunch: other ambassadors, some company’s head of licensing and branding, a gaggle of female prison guards, a Bank of Israel statistician, and prominent rabbis.

Everything is on offer—higher education, mini-sandwiches, cheap health care, United Airlines tote bags. But make no mistake: Admission is exclusive and by invitation only.

And, of course, there were the VIPs. Netanyahu had broken his leg playing soccer and was on crutches, so he made his appearance through a videotaped message. President Shimon Peres came, though, as did Peter from Peter, Paul and Mary and one Supreme Court Justice. Marisa Tomei was rumored to be there, but the next day neither TMZ nor Perez Hilton had any mention of her presence.

As an American, I was a welcomed guest at this party, just like, as an American, I am a welcomed guest in Israel. Everything is on offer—higher education, mini-sandwiches, cheap health care, United Airlines tote bags. But make no mistake: Admission to both is exclusive and by invitation only.

I made the choice to come to Israel for the most spoiled first-world reasons: to shake up my life, to attend fancy parties, and to be the exotic foreigner.

The infiltrators come for the most basic third-world ones: to save their life, to escape a brutal regime, to attempt to feed their family. It all came together on the Fourth.

I left the party late, not leaving until the cruise-line bartenders had taken off their captain’s hats and started packing up their bottles. As I walked out laughing and joking with friends, a team of cleaners swooped in. African men, short from a childhood of poor nutrition, scarred from a trip across the Sinai, these were the lucky ones who had finagled a work permit or found an employer willing to risk a fine. In they silently marched to pick up the crumpled programs and empty plastic cups. Grateful, like me, for the invitation.