All the Gin Joints

The deserts of Morocco are wide and golden. Trust nearly 200 American college students to track down and guzzle whatever alcohol lurks in the sands of the Islamic kingdom.

Early one Sunday morning I drove through the quiet streets of Casablanca with 196 college students that I was leading on a summer voyage with Semester at Sea. I had recently read an article that quoted a line from a recent Pew Global Attitudes Survey: “The image of America has improved markedly in most parts of the world, reflecting global confidence in the United States.” So at that moment I was a hopeful guy—the archetypal innocent abroad—as we drove in 14 minivans on a four-hour ride to Marrakech, the Berber city that long ago gave its name to Morocco.

We arrived in time to go to lunch at a restaurant near Jemaa el-Fna, a tumultuous square swarming with tooth pullers, snake charmers, monkey handlers, and gawking tourists. One student disappeared that afternoon, and given the grisly history of Jemaa el-Fna (where, until the 19th century, as many as 45 criminals were beheaded in a day, their heads pickled and stuck on the city gates), I reasoned it might be wise to find him before he had the opportunity to break any Moroccan laws.

Our rescue parties went off in different directions from the main square, angling into the narrow streets of the old city, drifting past the markets laid out according to the goods they sold—basketry or leather goods, copperware or jewelry, goat skins or stringed instruments. The frantic search ended a few hours later when we discovered our AWOL student enjoying a beer near one of the many souks. He was dressed in a jellaba and gazing with glazed eyes at a sign that said “Timbuktu—50 days by camel.” The students cheered and ran to his side. From the clinking of bottles in their backpacks, I knew that some students had ventured beyond the winding streets to the supermarkets on the main avenues. I was grateful that crimes and beheadings had been averted, but the sound from the backpacks was ominous.

The next morning at seven, we had to comb through hotel rooms to find the four young men who had crawled back from a night of clubbing a few minutes before daybreak. One pale-skinned, studious-looking boy we found sleeping among the suitcases in the back of a van. The other three eventually staggered onto the vans, enough 150-proof alcohol fumes drifting from their pores to make them a genuine biohazard.

Our vans snaked through the stomach-churning switchbacks of the High Atlas Mountains for nine hours as we made our way from Marrakech to Ouarzazte and the Draa Valley. We had distributed enough meclizine to put a small army to sleep for a week, but after a few minutes into those twisting roads I knew some people would suffer mightily for their nighttime pleasures. A bit before sunset, we traveled through the landscape of the movie Babel, traversing the exact place where, in the movie, a stray bullet shatters the bus window and wounds Cate Blanchett. We had come to the brink of the Sahara Desert. Right before we stopped, I heard a sharp crack as some projectile hit the windshield of our bus, and veins spread across the glass in the blistering sun. I was a bit dazed myself from the meclizine and, in that paranoid state, considered the possibility of a bullet, though better judgment would have blamed a rock kicked up in our passing. But what seemed too amateurish a piece of foreshadowing for a creative writing workshop turned out to be an apt warning of what was to come.

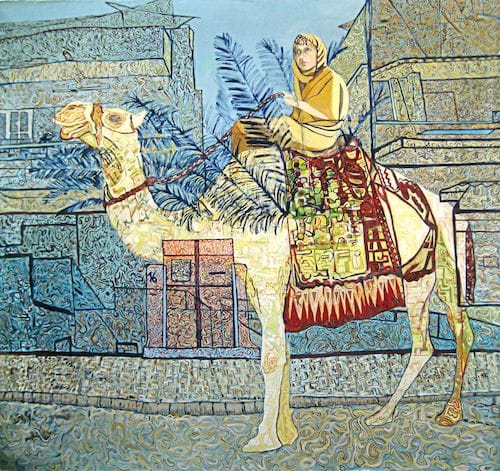

We stood under the date palm trees, a dry wind stirring the still-sizzling air, and we waited for half our company to seat themselves on the 95 camels that were lined up for the trip to the Berber village. One of the drivers (coincidentally, but truly, a man who had played the part of the driver on Cate Blanchett’s bus in Babel and could have doubled for Peter Lorre in Casablanca) talked to me about America and Morocco.

“Morocco’s people love America,” he said, running his chubby fingers across his brown moustache. “The American dream is ours, too. We all pursue happiness, eh?” He nodded toward the Berber man standing a few yards from us. The Berbers were the original inhabitants of Morocco, and their name itself means “free people.” “The Berbers, too,” he said, “they have some of the American spirit.” The Berber had his hood pulled tight around his face, and his eyes burned like distant suns against a dark sky. Whether he was an independent spirit or not, it was hard to visualize him in a house in a trim and geometric American suburb, sipping a Bud Light. He fit here—in the stark and beautiful furnace of the Sahara.

By three a.m., the closest thing to a Bedouin or Berber at our campsite was the one student roaming among the silent tents talking in a slurred squawk on her cell phone.

Half of us trudging through the desert, the other half riding camels, we arrived at the Berber village to discover that the Berbers (even the one who had been standing a few yards away from me earlier) had all gone into the mountains for the summer. So, instead of Berbers, the students got a group of Moroccans with toothy smiles serving booze at a welcome table. The six students who had purchased quarts of single malt scotch and designer vodka at stores in Marrakech didn’t need the extra booze. But, I suppose to be good sports or because they were exhausted from their two-mile trek, they bought drinks anyway.

By three a.m., the closest thing to a Bedouin or Berber at our campsite was the one student roaming among the silent tents talking in a slurred squawk on her cell phone. I never did figure out how she got service amid the nine million square kilometers of sand, but, miraculously, she was holding a loud conversation—on speakerphone—with a friend 3,600 miles to the west in New York City. Around the same time, people started yelling for her to shut up. A few other drunken voices got into the discussion. One of them, I suppose, was named Richard, as I heard his nickname used a dozen times. Perhaps he was a dental student, because there was talk of his looking in her mouth. At first, I lay there, like any sane trip leader, praying that everyone would just pass out and let me go back to my dreams of Berbers in the majestic Atlas Mountains.

But her voice only got closer and louder.

“So, big deal,” she whined to her friend, “I slid down the gangway last week and I was naked from the waist down. Forgot to put on underwear. Is that such a crime? They’re so academic on that ship!”

She sniffled into the cooling desert air. “I don’t know where I am. I feel like a nomad in the Sahara!”

Into the moonlit night I went, explained to her that she wasn’t a nomad and that if she didn’t keep quiet, she wouldn’t be a Semester at Sea student come the next day. She tossed a stray blond strand into the motes of moonlight that framed her hair and gave me the same uncomprehending look that the Berber had earlier, but she went to sleep right there on the ground, under the cold stars and the clear desert sky. At sunrise I awakened to her rooster crow, “Oh, shit, I fell asleep on the ground. Damn!”

She paused to spit. “Dude… the Sahara is sandy!”

In the purpling morning light, I discovered garbage and bottles strewn all over, two tents collapsed, three young men buried under the folds of one of them, two young women unable to find their clothing, and one student with a lump on his head caused by a punch thrown by someone he never saw. As much as I wanted to have faith in the American ideal, in that instant I doubted even the Founding Fathers could have envisioned a document to control the drinking habits of some American college students, the need for more camels per capita in Morocco, or the overabundance of sand in the Sahara.

The bus driver from Babel stood by my side and looked wide-eyed at the devastation magnified through the extra large orbs of his tinted glasses.

“Ah,” he said, in the nasally tones of Peter Lorre explaining a mystery of the universe to Humphrey Bogart. “Animal House, I’ve seen the movie.”