Boots March on Bolotnaya Square

This winter, a burgeoning protest movement laid its cornerstone in a former swamp and up grew hope. Our correspondent talks to protesters, editors, commentators, and Kremlin-watchers in anticipation of this weekend's election and what comes next.

Late last year, my friend Misha bought a new pair of boots. He planned to wear them to an unsanctioned protest in Moscow, so he was most concerned that they be warm and they be light. The forecast for Dec. 10 was for bitter cold with a chance of brute force. “I thought I would have to run,” he told me.

There was a third criterion for the boots—a telling one: They had to be found in Heathrow Airport. Like many of the Muscovites who have joined the demonstrations of the past three months, Misha spends a not-insignificant amount of time outside of Russia. Like many of his cosmopolitan, well-educated peers, Misha used to think seriously about immigration. He ascribed to the general consensus of the middle-class that things in Russia could not get better but could get a hell of a lot worse. That he is a political journalist who has run afoul of the Kremlin in the past did not improve his personal prognosis.

An estimated 60,000 people turned out for the Dec. 10 demonstration in Moscow, the largest anti-government rally since the fall of the Soviet Union. It was followed by larger gatherings in the subsequent weeks, culminating in a massive turnout Dec. 24 at Bolotnaya (“Swamp”) Square on the Moscow River island across from the Kremlin, where at least 150,000 people braved subzero temperatures to demand change.

The police stood by. No one had to run.

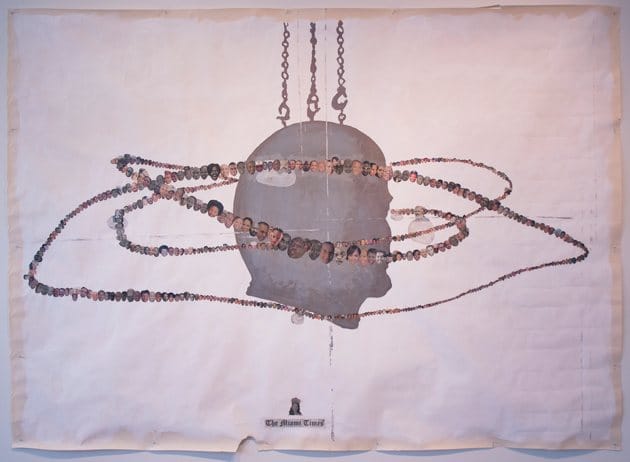

Today, anti-government protest rings the capital, literally. Last Sunday, a human chain formed a White Ring around the Kremlin; the weekend before, it was a vehicular White Circle of Solidarity, with drivers blocking traffic and waving their signature white ribbons. The old Soviet term for demonstration, “meeting,” is used less frequently than the new Russian “flashmob.” Observers and participants characterize the movement as a surprise uprising of the “creative class”—a show of dissent that stands in marked relief from the violence of the 1917 proletarian revolution, the messianic clash that ended Communism in 1991, and the pathos of pensioners ruing the fall of the Soviet Union since then.

On the eve of the most important presidential election in two decades, Misha has no thoughts of leaving Russia: “There is a lot of confidence,” he told me over Skype, bouncing his daughter on his knee. “This is hugely important.”

The Moscow protests, mirrored on a smaller scale in Russia’s largest cities, began as a public condemnation of federal parliamentary elections held on Dec. 4, in which United Russia, the country’s largest political party, lost its majority for the first time since 2007.

Because United Russia is the party clearly identified with and supportive of the policies of former President Vladimir Putin and his successor Dmitry Medvedev, its setback was indicative of a serious turn in public opinion against the current regime.

Anti-Putinism has united disparate factions, from nationalist to environmentalist, and elevated personalities from whistleblower to mystery writer.

Official results gave United Russia 49.6% of the vote, a drop of one-third in its strength in the parliament. But amateur videos of ballot-stuffing, repeat voting, and election worker vote-verification hijinks circulated on YouTube and Russia’s robust blogosphere, suggesting that the party of power had fared even worse than the numbers showed.

Unfair elections have a healthy precedent in Russia, where opposition candidates are regularly handicapped with onerous registration procedures and minimal access to the mass media. So, too, does acceptance of such tactics by an electorate whose passivity and abysmal participation rates are as predictable as vote-rigging. This time, however, the cynicism of the state outdid that of the liberal elite. The outrage was instantaneous. Quickly moving offline, the cry “For Fair Elections” took to the streets. There, it found strength and new demands.

Having dispatched the “systemic opposition” (as the emasculated political alternative to Putin is formally called), the Kremlin now heads into Sunday’s elections facing something much more dangerous—a nascent civil-rights movement.

On the morning of Feb. 1, a giant banner appeared on top of a building directly across from the Kremlin. It showed Vladimir Putin’s vaguely extraterrestrial head with a large X over it, alongside the words: “Putin, get out.” Activists from the political group Solidarity had hung it overnight. It stayed up long enough for the political elites who travel to work in black cars with traffic-busting flashing blue lights on the roof to get a good look. One of the founders of Solidarity, Ilya Yashin, said the banner’s meaning was “obvious.”

“It’s a protest against the political course that Vladimir Putin has executed over the past 12 years to establish a regime of personal power and scorched-earth tactics against any real politics in Russia,” he told Radio RFI. “We consider Vladimir Putin to be the primary obstacle to serious reform…and we call on him to give up power and all governmental responsibilities.”

The fact that Yashin, who was arrested briefly at one of the early December rallies but survived the banner incident without repercussions, needed even to explain the action highlights one of the peculiarities of this protest movement. Anti-Putinism has united disparate factions, from nationalist to environmentalist, and elevated personalities from whistleblower to mystery writer. They all agree on one thing: Vladimir Putin, the once and future president who has controlled the country from his backseat as prime minister for the past four years, will soon be back in the driver’s seat.

Unlike past dissenters, today’s protesters reject the notion that they owe their welfare (be it good or bad) to the state (be it benevolent or corrupt).

Both official and independent polls show that while Putin’s popularity has declined below the 50% needed to win outright on March 4, he will certainly prevail over any of the four candidates from the “systemic opposition” who will face him in the run-off election to follow. The question is not whether Putin will return to the presidency, but when. For a movement that wields “Putin, get out” as a rallying cry, one would expect that this certainty would be something of a buzzkill. Instead, opposition leaders see March 4th as a test for Putin—one that he can only fail, even with an electoral victory.

“It’s a paradox,” explained Lilia Shevtsova, a veteran Kremlin watcher with the Carnegie Endowment and longtime member of the liberal opposition. “If Putin goes to the second round, he gains legitimacy [in the eyes of the voters]. But in the eyes of the system, he will be a lame duck.”

Having never had to balance one against the other, there is a good chance that Putin will gamble against a measure of legitimacy to shore up his authority over the political elite—the state bureaucracy and regime functionaries who have all seen Yashin’s banner and the smaller versions of it flying in Bolotnaya. Already, Kremlin sources are predicting a statistically inconceivable first-round win.

Shevtsova acknowledges that it is tempting to hope that Putin will take that gamble—after all, it was the brazenness of the stolen parliamentary elections that ignited the protests. A first-round theft would just add fuel to the fire. But the fire, she says, is in no danger of dying, whether Putin plays by the rules or not.

“If the priority is to get rid of the autocracy, we need to change the rules of the game,” she said. “Putin in the presidency for the next six years will be understood as a disaster … and that is the best scenario.”

Unchallenged since he came to power in 1999 as a relative unknown KGB official tapped to succeed ailing Boris Yeltsin, Putin has himself relied on the “disaster” scenario to stay in power. He successfully positioned himself as a bulwark against the lawlessness and economic turbulence of the 1990s—when radical reform threw a vulnerable population into a financial and social distress that seemed poor compensation for having a wide range of politicians to choose from.

Putin solidified his popular support with a corrosive social compact: stability and relative affluence in exchange for a politically passive society. He consolidated his political power by curtailing regional elections and the independent press. He ensured control with the same promises to his loyalists: state schools, government salaries, and factory wages are as valuable chips now as they were under the Soviet regime. The system used to be called “one-party rule”; under Putin, it is called “managed democracy.”

Just how closely this system was “managed” became shockingly evident when Putin maneuvered Dmitry Medvedev into the presidency four years ago but continued to rule unchecked, dictating policy and “correcting” his protégé’s false moves. Then, last September, Putin announced that they would swap roles at the end of Medvedev’s tenure. The audacity of this announcement has been described repeatedly as a “humiliation” and “insult.”

A connected, aspirational, smart generation has spent the past 10 years creating communication channels completely independent of the Kremlin and a language beyond Putin’s ken.

Given the weight of the insults inherent in Russia’s centuries-long history of paternalistic government, the argument that its intelligent class finally has simply grown tired of being played for fools is a partial explanation at best. In Russia, being “fed up” is not logically followed by civic consciousness.

“The situation has changed by the emergence of a generation that has never lived behind barbed wire and was never isolated from the outside world,” says Boris Tumanov, a political columnist who predates said generation. Unlike past dissenters, today’s protesters reject the notion that they owe their welfare (be it good or bad) to the state (be it benevolent or corrupt). They have more to lose than their parents ever did—the freedom to travel, buy nice stuff, and berate the government from the confines of their well-furnished kitchens, fashionable cafes, and high-speed chatrooms—but today’s middle-class does not equate personal comfort with a functioning society.

“It no longer suits [us] to live in this fortress of well-being, one step out of which reveals nothing but degradation,” says Ilya Krasilchik, editor of the weekly magazine Afisha, who played a prominent role in organizing the Dec. 24 rally at Bolotnaya.

And so they are championing a most un-Russian concept: social responsibility.

Krasilchik is one of a handful of journalists whose organizational role and online reach in today’s “yuppie vanguard” of opposition has inspired comparison with a latter-day Russian revolutionary intelligentsia. It’s an apt analogy if you look at the youth, privilege, and friendship of the players profiled in the recent New York Magazine article. For most of these “New Decembrists,” Bolotnaya was a first foray into activism and a political debut.

“I said Afisha would become political when there are politics to discuss,” Krasilchik told me. “And that has happened rather suddenly.” This week’s edition features 75 pages on the elections and the opposition—pages once reserved for art galleries, dance parties, and exotic vacation destinations.

But Krasilchik is the first to dispute his motivation as “revolutionary.” He places his job and his family before activism and demurs that “we should not exaggerate our role.” Absent a charismatic, politically adept leader (there are some with each skill, but none with both) and a strategic consensus, the Moscow demonstrators have more in common with discontented Occupiers everywhere than with the hot-headed foes of tyranny executed by the Tsars of yesteryear. Fashionable, affable, and well-off, yes—martyrs for liberty, no.

Still, it would be churlish to write off the contributions of this new faction. Yes, this weekend’s human chain of protest was conceived of by a fellow who this time last year was on a panel entitled “The Hipster—Who Is He?” and yes, the host of the most controversial TV show of the past few weeks is a socialite who has been called “Moscow’s Paris Hilton” —but both represent a connected, aspirational, smart generation that has spent the past 10 years creating communication channels completely independent of the Kremlin and a language beyond Putin’s ken. Those are excellent resources for the opposition. Many see the blogosphere as a source of potential leadership.

“Some of these guys are pretty good managers and organizers; it’s just they didn’t need these qualities outside business before,” notes Ilya Klishin, a blogger whose Facebook page, “We were on Bolotnaya Square and we are coming back,” has more than 22,000 followers. Klishin also disagrees that politics is a recent fashion among hipsters. “It has been a long and conscious process of the last two or three years,” he asserts.

To be sure, civic consciousness does not happen overnight, but only on Facebook does three years qualify as a “long process.” This “creative class” has shown innovation in slogans, ingenuity in subversive acts, and a great deal more humor than any protest Moscow has seen before. But can these new dissenters create a concrete agenda? A working consensus to unify the movement?

Klishin (and so many of the others who “were on Bolotnaya Square and are coming back”) was in grade school when Putin began building his “power vertical.” It remains to be seen whether they have reserves of patience needed to cultivate a true civil society in a country that has struggled to produce one for centuries. With no consensus on how to approach the March 4 election, aside from “no vote for Putin,” it is clear that Klishin is right about one thing: “There is no opposition. There is a zeitgeist.”

“I saw what was happening on Bolotnaya,” said Tumanov, the political commentator, who feels that most foreign observers need a crash course on Russian totalitarianism and liberal thought. “Such naïve slogans—’Putin out!’ ‘Annul the elections!’ These are meaningless demands,” he insisted. Chiding both the “impatience of intellectuals” and the Western media for forecasting a popular uprising that will end the current regime, Tumanov sees the danger of disillusionment around the corner from Bolotnaya.

The last three months of mass mobilization and personal participation have only deepened the cultural gap between middle-class Moscow and the Russia that still has more to lose than gain from upheaval.

“Twenty years ago there was the same naïve faith. That by adopting the word ‘democracy’ we would become free and rich. But the removal of the Soviet regime just left us with a ‘the cat’s away’ kind of holiday and in the end, all of my colleagues who had called me a skeptic were saying the same thing— ‘Russia, after all, is Russia. We can’t hurry this process.’”

Tumanov’s not alone in insisting that Russian society is still largely burdened by a “peasant psychology” that bends to the will of an all-powerful state. Most analysts describe a clear divide between rural, less-educated Russians (dependent on the state for salaries, social services, and news) and the urban Russians who are moving offline and into the streets. The former still outnumber the latter, and the Kremlin is not shy about muzzling attempts to breach the gap. In the past two weeks, at least three media outlets with national reach and objective coverage have come under overt pressure. There were also reports that authorities doubled the price outside Moscow of Afisha’s first-ever political edition, “so the regions won’t know what’s going on,” as one Facebook comment saw it.

But is it possible that it is the Bolotnaya movement—the protesters who can listen in person to the latest speech from the corruption-buster-turned-opposition icon, Alexei Navalny, or go online to find out where to stand to make the human chain complete—is it possible that it is they who don’t know what’s going on?

“We don’t have any way to know how many of us there are,” Krasilchik said when I asked if a Putin defeat at the polls is completely out of the realm of possibility. “We underestimated the low-level support for United Russia [in the parliamentary elections]. So perhaps we are underestimating Putin’s support. It’s possible.”

In other words, the last three months of mass mobilization and personal participation have only deepened the cultural gap between middle-class Moscow and the Russia that still has more to lose than gain from upheaval. The one is literally ignorant of the other.

Leon Aron, a researcher at the American Enterprise Institute, says the question is not whether the rest of the country will join the protests. Russia Two, as he calls Russia outside of Moscow, “is not rebelling against the regime. The real issue is, will it rise up in its defense?”

Today it appears that the most that can be expected from Russia Two is that it will go to the polls and cast a ballot for Putin. But that is no longer sufficient defense for the beleaguered Putin and his comrades. So does Russia Two even matter? Or is it Russia One that’s running the show?

“That Russia is in charge,” says Aron of the protesters, a numerical and political minority, pointing out that all modern revolutions in Russia are launched by “a tiny sliver of urban population.” But Aron, too, wants to qualify the movement: “It’s not a revolution in progress. It’s the beginning of a nationwide civil-rights movement that has potential of changing not just the regime but the Russian political culture.”

In fact, today’s situation appears to suggest that the best chance for changing the regime lies with changing the political culture. The demand for fair elections is giving way to a call for a fair electoral system; the concerns about lack of leadership have receded, replaced with calls for consensus and strategy. The underlying “respect for moral dignity,” says Carnegie’s Shevtsova “is a huge contribution.”

My journalist friend Misha Fishman agrees: “It’s important not that they, (and I mean ‘we’), point to the Kremlin and say, ‘The thieves are there.’ What’s important is that people see each other and see themselves as a community.”

Sentiments like these may ring wildly naïve in a matter of days, should the election results (or more likely, the street response to the results) provoke violence. Some 30,000 volunteers have signed up to be poll monitors on Monday, and it seems fair to say that for things to go well for Putin, their presence must be either blocked or ignored, escalating the distrust that is at the root of the dissent.

Alexei Simonov, a veteran human-rights advocate associated with the Moscow Helsinki Group and the Glasnost Fund, says the presence of “an uncowed, sober opposition” has made “those in charge of Putin’s campaign a bit frightened—they are tensely watching for their future.”

For now, the Kremlin response has been almost comedic. First there were concessions: promises to raise the legal drunk-driving limit and to fly football fans to matches in Poland for free. Then came competition: pro-Putin rallies tens of thousands strong, after which participants approached journalists to ask where they could pick up their payment. This week brought a time-honored ploy: revelations that the security forces uncovered an Ukrainian/Chechen conspiracy to assassinate the president.

“Such things shouldn’t be an obstacle, and they will not be,” said the ostensible target with characteristic bravado.

But no one doubts that Putin may orchestrate something worse than cheap publicity and fake elections. Whether he opts for a crackdown or for a less physical outrage against the growing dissent, the movement will certainly change after the elections. Violence scares participants; but anything less could draw down the numbers out of sheer inertia. Civil-rights movements demand a great deal of patience but also the occasional water cannon on national television.

Early in the protests I asked my friend Andrei, who describes himself as “opposition light,” if he was demonstrating. Of course he was. “But sincerely? Or just for kicks?” I asked him, knowing his deep cynicism, the long periods he has spent out of the country, and his general attitude towards cool things to do.

“Can’t it be both?” he responded.

The surprising momentum of the past three months tells me “yes”—standing on principal has proved to be wildly popular. (Who doesn’t want to be part of “a flashmob that will go down in history?”) But will it still be true next Monday, next month or next March? There was a straw poll on Facebook this week—where is the best spot to hold a March 5 anti-Putin rally? Bolotnaya? Triumfalnaya? Some have commented on the symbolic strength of Triumphal Square; fewer on that of “Swamp” Square. After much negotiation the protesters secured Pushkin Square for the rally. It’s a more central venue than the once-obscure Bolotnaya, and a more traditional demonstration spot. Perhaps there is symbolism in the movement’s emergence from the “Swamp.” Perhaps their next step is to abandon their signature White Ribbon.