Burying the Present

Thirty years ago, two friends created a vision of the future—a space opera put to tape—and buried it in a time capsule. Listening again today, it turns out we remember the past as it never quite was.

In the spring of my final year in elementary school, my teacher, Mr. Cheatham, announced that our class was going to make a time capsule. Our task was to gather relics that represented our lives as 12-year-olds, pack those items into a brown plastic pipe, bury it in the ground, and dig it up six years later, when we were high school seniors. Our goal was to document reality, as we knew it in 1983, so that we could say something interesting to our future selves.

One of the more problematic of Mr. Cheatham’s time-capsule assignments was to think ahead to the future and write about what life might look like in 1989. To me, life in 1989 didn’t seem all that interesting, since it promised only a variation of what I was already doing: attending a public school in Wichita, Kan. Befuddled by the lack of compelling possibilities, my friend Eric and I lobbied the teacher to let us imagine life in a more distant and exciting epoch. Using the most cutting-edge media technology we knew—the audiocassette recorder—we aimed to portray our vision of the future in the form of a radio drama: Eric would provide the voice-over, I would improvise a piano score; we would both collaborate on the script. Eventually Mr. Cheatham was won over, and when our class’s time capsule went into the ground, it included a three-minute tape recording of our visionary magnum opus, which we entitled “1999: A Space Adventure.”

Six years later a handful of my classmates returned to our old elementary school, where we dug up our 1983 relics and brought them into a classroom for inspection. Time and moisture had taken a toll on some items, but we enjoyed leafing through old photos, newspaper articles, and homework assignments, marveling at how much we had changed in six years. As it turned out, one of the least-compelling items in the time capsule was the cassette tape of “1999: A Space Adventure.” Whereas the other items (drawings, essays, old bubblegum wrappers) carried a clear connection to our lives as 12-year-olds, our faux radio drama about the wonders of 1999 proved to be a static-plagued, scarcely comprehensible tale of alien spaceships and laser battles. Eric and I listened to it once, chuckling with embarrassment, before moving to other, more relevant time-capsule relics.

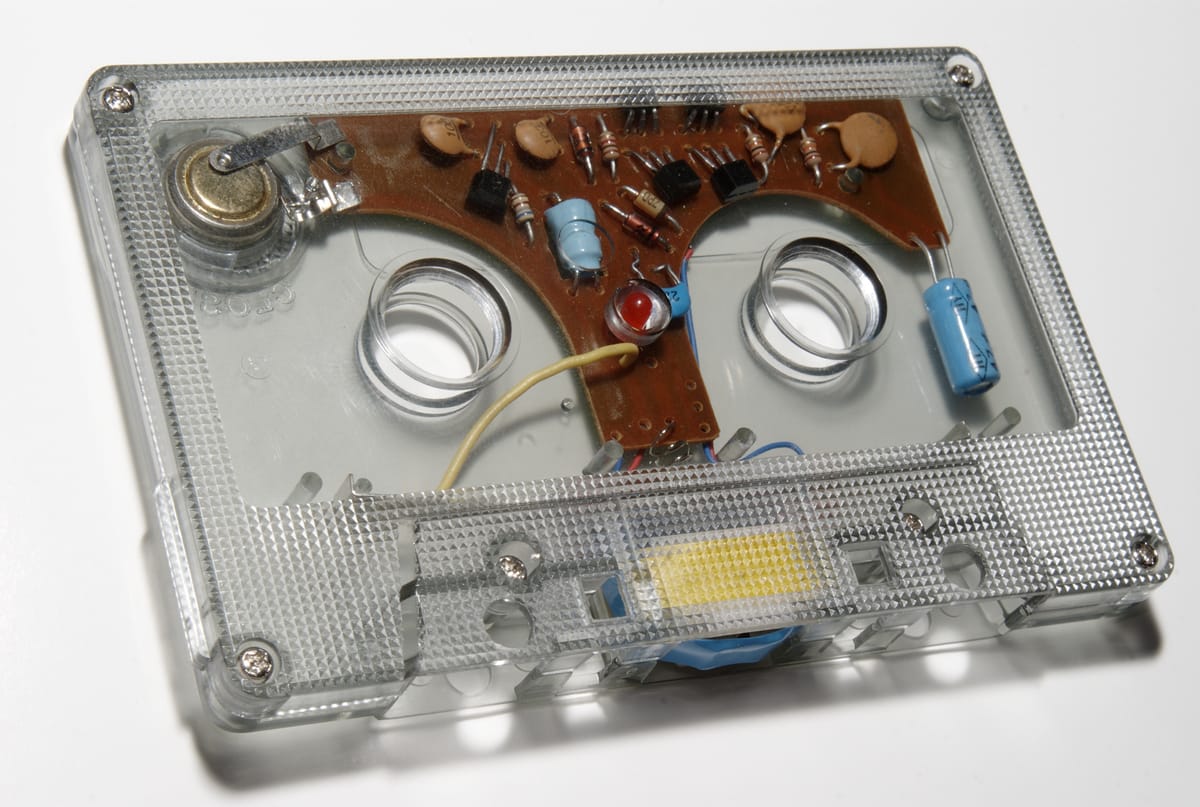

As the actual year 1999 passed by, the audiocassette—its intricate system of gears and belts and iron-oxide-coated tape—began to look strange and fanciful.

I couldn’t bear to throw out the tape, so I took it home and stashed it in a cardboard box alongside other items from my youth. For years afterwards I would occasionally see it while searching for elementary-era trinkets or drawings or football cards. In time, I became intrigued with the old tape less for its content than for what it represented as a physical artifact of another era. As the actual year 1999 passed by and popular media technology became more exclusively digital, the tangible workings of the audiocassette—its intricate little system of gears and belts and iron-oxide-coated tape—began to look strange and fanciful, as if it were a hypothetical steampunk invention instead of an everyday 1980s technology.

Earlier this year I digitized all my old audio and videotapes in the hope of preserving them for posterity. As I listened to “1999: A Space Adventure” for the first time since 1989, I realized it was so warped from six years under the soil (and 24 years in storage) that it would be impossible to appreciate as a digital file unless it were accompanied by visuals. Since my nephews are good at drawing—and since they’re roughly the same age I was when I recorded the radio drama—I recruited them to help me with the task. Once we had deciphered the plot (men from a spaceship called the Superprize crash-land on a planet called Degoba and get into a laser fight with aliens known as Waurons), my nephews got busy drawing.

The more my nephews drew, the more I became enthralled at the way creative possibilities for preadolescents had transformed in 30 years. In 1983, when Eric and I recorded “1999: A Space Adventure,” a DIY cassette felt like a sophisticated technological endeavor, but our actual creation—a pretend radio drama, recorded in real-time, with piano-driven sound effects—was a throwback to the pre-TV days of the 1930s and ’40s. By comparison, my nephews’ illustrations approximated what they were seeing online and on TV in 2013. Utilizing the drawing and animation apps on their iPad, they transformed my semi-coherent 1983 sci-fi drama into a quirky and engaging animated cartoon. What in 1983 would have required a professionally equipped animation studio was accomplished by a couple of north-central-Kansas farm kids in a week’s worth of spare time.

When I expressed my astonishment, my nephews shrugged. To them, the things they could do with their iPad—watch movies, shoot videos, mix music, animate cartoons, Skype their cousins in Hong Kong—felt normal.

Just over 100 years ago, in the spring of 1913, a 42-year-old journalist named Frank Parker Stockbridge wrote a Popular Mechanics article expressing wonder at the extent to which technologies had transformed since he’d been born. “Never have the creative forces of mankind moved so fast as in the lifetime of us who are now on earth,” he gushed. “Never before have there been so many people in the world eager to know what the world is doing, and how it is doing it.” Detailing the devices that had “come into existence in the lifetime of men who are still young”—electric lights, motion pictures, automobiles, airplanes, bicycles, telephones, phonographs, typewriters, fountain pens, alarm clocks—Stockbridge noted how the young people of his age possessed “new perceptions of the destiny of mankind, new inspiration to great thoughts, and a new conception of this big world of ours.”

When I first discovered Stockbridge’s article in the Popular Mechanics online archives last year, I found its language relatable. Swap out the technological specifics, and you could almost end up with an article that applied to the current day. Since the 100th anniversary of 1913 was just a year away (and since any bit of historical ephemera automatically becomes newsworthy once it hits a round-number anniversary) I filed the article away, thinking it might eventually be fodder for an essay of my own.

By the spring of 2013, however, my experience with my nephews and the time-capsule cassette tape had changed the way Stockbridge’s article resonated. Whereas I’d initially related to his upbeat cataloguing of recent inventions, now I began to notice the ways the he’d tried to put everything into perspective. At one point in the article he mentioned his childhood memory of an elderly aunt who, a couple generations earlier, had once walked three miles to borrow fire from a neighbor, since matches hadn’t yet been invented. “It was a real shock to me,” Stockbridge wrote. “So far as I knew, matches had always existed. I could not conceive of a universe without matches, any more than the youngster of today can imagine a world without telephones, electric lights or automobiles. Youth seldom realizes that the commonplaces of today were the wonders of yesterday.”

In mentioning the mindset of youth, Stockbridge was really reflecting on the situational nostalgia that emerges when one encounters middle age. When, in the manner of a time capsule, we aim to ascribe relevance to the relics of the not-too-distant past, we often wind up interpreting both past and present in a way that underscores how difficult it is to truly understand either.

In the 2002 book Time Capsules: A Cultural History, scholar William E. Jarvis points out that popular American interest in creating time capsules peaked in the middle of the 20th century, and was already in decline by the 1980s. Jarvis adds that the arbitrary items contained in most time capsules rarely provide historical information that isn’t better represented by artifacts that have been collected and archived in an ongoing manner. By the early 21st century, the phrase “time capsule” had effectively come to represent a hypothetical, a la carte phenomenon: not a physical object to be exhumed so much as a metaphorical examination of personal and cultural objects specific to a time and place.

This notion was the organizing principle behind one of this year’s more intriguing art exhibitions, The New Museum’s “NYC 1993,” which was billed as “a time capsule, an experiment in collective memory that attempts to capture a specific moment at the intersection of art, pop culture, and politics.” Showcasing both famous and obscure art that had been made or shown in New York City in 1993, the exhibit aimed to give the viewer a sense for what it was like to encounter the city’s artistic landscape 20 years earlier. The show was conceived in part to trace the evolution of art’s interplay with social issues like gay rights, health care, and gun control, but—two decades on—the form of its various installations proved as telling as their content.

Publicizing one’s most banal private thoughts in this way apparently qualified as conceptual art 20 years ago.

Indeed, amid the better-known installations (like Charles Ray’s creepy “Family Romance” and Janine Antoni’s whimsical “Lick and Lather”), I found myself attracted to artworks that felt as if they had intuited some shabby, proto-technological vision of the future. Sean Landers’s “[sic],” for example, was an unedited, stream-of-consciousness diary of the artist’s thoughts and fantasies in “every ugly detail,” scrawled on 454 sheets of yellow notebook paper. Publicizing one’s most banal private thoughts in this way apparently qualified as conceptual art 20 years ago; viewed in 2013, it felt as familiar as any baroque collection of ramblings from the blogosphere. Similarly, Karen Kilimnik’s “Heathers” (which obsessively plays and pauses the author’s favorite scenes from the eponymous 1988 Wynona Ryder movie) looked like a premonition of how we’ve come to experience movies in the age of streaming video, and Lutz Bacher’s “My Penis” (which loops a clip of William Kennedy Smith talking about the titular organ at his 1991 rape trial) played out like any number of satirical YouTube remixes of current-events reportage.

At the fifth-floor entrance to the exhibit, New Museum curators had set up 12 TV sets—one for each month of the year—to create a video timeline that blended screen-text and archival footage to recount global events from each day of 1993. Major headline moments like the World Trade Center bombing and the Oslo Peace Accords were represented, but I got the strongest mnemonic jolt from the more tangential, pop-culture-slanted historical references. When one of the TV screens briefly alluded to the debut of Nirvana’s In Utero album, for example, I recalled anticipating its release that year, but I also remembered the fickle sense of regret I’d harbored at not having discovered Nirvana earlier. I was a music-obsessed Oregon college student at the time, and as much as I loved going to shows by Portland-scene bands like Pond and Crackerbash and Drunk at Abi’s, I felt like I’d missed out on a more seminal sense of zeitgeist that had existed in Seattle in, say, 1988.

By embracing that attitude, of course, I wasn’t fully aware of what was taking place in Portland in 1993. Of the many local musicians I chatted up after shows at a Burnside Street storefront called the X-Ray Café, one was a skinny, tired-eyed singer-guitarist who played in a band named Heatmiser. By the time this soft-spoken young musician drove a steak knife into his chest in Los Angeles 10 years later, he had gone on to become one of the most iconic and revered singer-songwriters of his generation. Nowadays, when I talk about my experience of Pacific Northwest zeitgeist, I don’t talk about my regret at having missed out on the rise of Nirvana; instead, I recall a moment I had no way of understanding at the time: I recall having met Elliott Smith before he was famous.

If time capsules have something to teach us, it may well come in the way they show us how bad we are at making sense of the present. This is, in a sense, an anthropological problem. As ethnologist Claude Levi-Strauss admitted when he visited the tribal cultures of Brazil 75 years ago, any attempt to document a moment is never separate from the received assumptions and expectations that surround that moment. “While I complain of being able to glimpse no more than the shadow of the past, I may be insensitive to reality as it is taking shape at this very moment,” he wrote in his book Tristes Tropiques. “A few hundred years hence, in this same place, another traveler, as despairing as myself, will mourn the disappearance of what I might have seen, but failed to see.”

When, in 1913, Frank Parker Stockbridge was celebrating the ways technology was creating “new perceptions of the destiny of mankind,” he had no way of knowing that mankind’s destiny was just months away from start of the modern era’s most horrific war. From the narrative vantage point of 2013, one can imagine his Popular Mechanics-endorsed optimism sliding into despair as new military technologies had an outsized role in killing and maiming 37 million World War I combatants and civilians. To assume this, however, would be to misapprehend Stockbridge’s conviction that technology was a force that created opportunities and solved problems. In 1920, just one year after the Treaty of Versailles, Stockbridge came out with an upbeat book entitled Yankee Ingenuity in the War, which outlined the “striking and inspiring examples of the technical achievements of America that went so far toward the winning of the Great War,” including a “wonderful” new apparatus designed to drop poison gas from the air.

As my nephews were quick to point out, the story’s key plot points had been stolen wholesale from the original Star Wars.

As for the person I was when I buried “1999: A Space Adventure” into the Kansas soil in 1983, my nephews provided me with some insights when they began the task of making video animations of the old tape recording. The starship Superprize, they recognized, was a playful allusion to the starship Enterprise of Star Trek fame, and the planet “Degoba” was an obvious rip-off of Dagobah, the swampy planet where Yoda lives in The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi. (To my credit, I was able to figure out that “1999: A Space Adventure” had been cribbed from 2001: A Space Odyssey.) Eric and I had included some of our own cheeky narrative flourishes (like a starship commander who enjoys reading comic books), but for the most part our tale was boiler-plated from well-known science-fiction franchises. As my nephews were quick to point out, the story’s key plot points—a starship laser battle, space pods crashing onto a desert planet, the theft of secret battle plans—had been stolen wholesale from the original Star Wars.

Intriguingly, the first installment of the original Star Wars trilogy debuted in 1977, when Eric and I were kindergarteners. By the time we’d begun creating our space opera as sixth-graders, the debut of Return of the Jedi was less than a month away. Amid the flurry of pre-release promotion and merchandizing for the film, Eric and I were no doubt experiencing sentimental longing for a movie that had first captured our imaginations half-a-lifetime earlier, mixed in with anticipation for its epic finale. In creating a make-believe radio drama about the future, we were probably less interested in the year 1999 than we were in the day, a few weeks hence, when Return of the Jedi would hit movie screens. For all its failings as a space-age vision of the future, “1999: A Space Adventure” had inadvertently captured a glimpse into the concurrent blend of nostalgia and expectation that characterized the moment in which it was created: It conveyed, in its own, semi-coherent way, a sense for what it felt like to be 12 years old in May of 1983.

Ultimately, the attendant charm and conceit of any time capsule is its promise of a conversation between past and future, since this is a theatricalized version of what we’re already doing on a daily basis. Any given technological moment is a story that has been assembled from other stories; when, at some later point, we dig it up and try to listen, it’s hard to know if there’s a difference between understanding what we’ve heard and cobbling together another story to take its place.