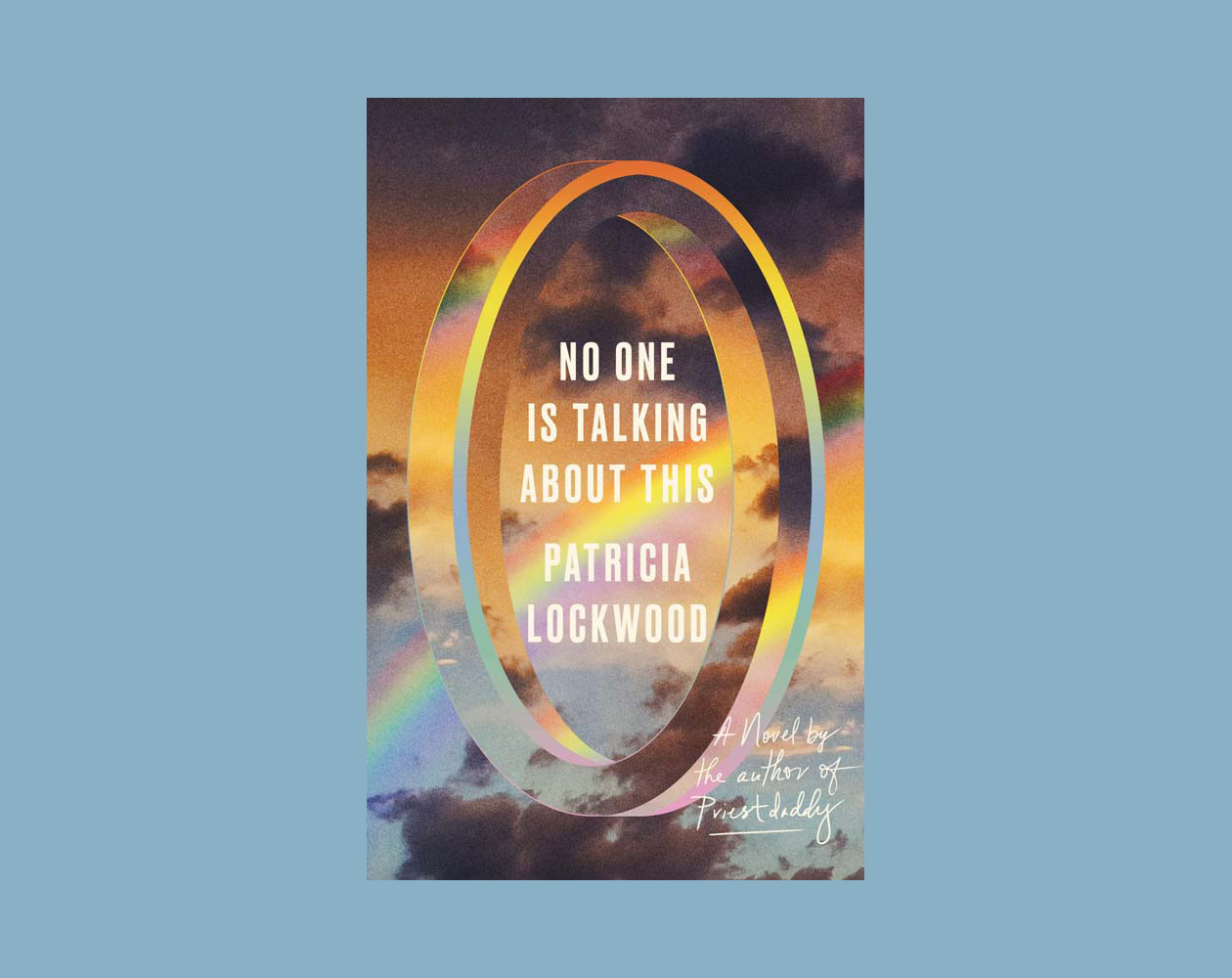

Week Two: No One Is Talking About This

In which we discuss the conclusion of Patricia Lockwood's No One Is Talking About This, in which we became very invested.

Rosecrans Baldwin: Welcome back, campers, to Summer 2021's edition of Camp ToB! Here's the boilerplate on how it works: Each week from now through the end of August, we're going to discuss a novel (selected by you, the readers), at a pace of two books a month. At the end of each month, you will vote for one title as your favorite, and at the end of the summer, the community will pick one of the three favorites to advance to a berth in the 2022 Tournament of Books (ToB).

FYI, the five books we read this summer that don't win the pennant may still qualify for the 2022 ToB's long or short lists.

I'm going to be facilitating the conversations this month, with Meave hosting in July, and Andrew in August. This week, we're talking about the second half of Patricia Lockwood's No One Is Talking About This, and our Activity Leader is California's Corin Balkovek. Hi, Corin!

Corin Balkovek: Hi, Rosecrans! Hi, everyone! My name is Corin and I'm a public services librarian in Humboldt County. I stumbled upon the Tournament of Books a couple of years ago, and since then have used it as a finding guide to books that might have slipped past my radar. This year was the first year where I actually read all of the participating books before the Tournament started, which felt like a big Book Person Special Achievement.

Rosecrans: Massively! So, this week we're talking about the conclusion to No One Is Talking About This, in which the story abruptly changes course after the narrator's mother texts her to say that something's gone wrong: The family has learned that the narrator's sister's unborn child has a debilitating genetic condition. As a result, Lockwood's narrator becomes "a citizen of necessity," and the story gets a lot bigger (and deeper, in my opinion) than its earlier Twitter-esque concerns.

Corin, broadly speaking, as you began the second half of the book, how were you feeling about things?

Corin: I enjoyed the style of the first half of the book because it made me feel like I was part of the inside jokes told by the Cool/Kinda Scary girl. I'm around the same age as Lockwood, and there were quite a few instances of observations that hit home for me (that particular affection you have for the people whose internet diaries you read at the beginning of the millenia, I'M LOOKING AT YOU).

Rosecrans: I mean, which diaries of mine did you find? Mwahaha. So, any specific observations that you highlighted?

Corin: Here's a few that I made note of:

"The theme song of a childhood show where mannequins came to life at night in a department store." I honestly thought this show was just a childhood fever dream, but after reading this I went down an internet rabbit hole and discovered that it was, in fact, real and so horrifying.

"…the whole audience conjured up the image of a man in a white T-shirt grinning over his shoulder…" Awwww, I hope Tom is doing OK.

"Enormous fatberg made of grease, wet wipes, and condoms is terrorizing London's sewers." I honestly think about the fatberg a lot. Like, too often.

But I wondered how universal those feelings would be. Would other generations feel the same buy-in as I did reading it, or would it just be a random internet thing that they skimmed past?

Rosecrans: So many times I found something revelatory or really insightful, I would think, do my parents have any idea what she's talking about?

Corin: Even with the nostalgia for the outdated internet, the first half of the book felt like what it was describing, the somewhat random scroll and skim of the world at large. That's enjoyable in its own way, but it wasn't until the second half of the book when I really began to be invested in what was happening.

Rosecrans: Right. And I have a feeling, based on the discussion last week, that lots of readers feel similarly, but also that lots of readers had a different experience, even the opposite experience. As I said, the second half of the book turns on a significant pivot—the plight of the narrator's sister and her unborn child—that is more real, so to speak, than some of the concerns of the first half. So, the first half didn't have you so hooked?

Corin: I enjoyed the first half of the book. But it was that second half that really grabbed me by the collar and slapped me across the face. Lockwood has a way to take the smallest observational detail, spin it around and work it over, turning it into something that is both her own and relatable and hilarious: the absurdity of search history phrases, complementary mini muffins in honor of a historical tragedy—

Rosecrans: I know!

Corin: That universal experience of smelling Subway bread. But she can make these phrases as lethal as they are droll, weaponizing them to hit you right in the gut. Toward the end of the book there is a phrase that the protagonist remembers seeing in the portal—"I am I because my little dog knows me"—that could easily be another example of the internet interneting something into a joke, but in Lockwood's hands it becomes a powerful moment of sorrow and of saying goodbye. It's internet nonsense turned nerve agent, and I couldn't tear myself away from it.

Rosecrans: "Internet nonsense turned nerve agent" should be a T-shirt, or perhaps the name of Elon Musk's next child.

As the book nears its end, the story deals in bereavement, its anticipation and fulfillment: In a cascade of moving moments, the baby's parents and the narrator say goodbye in different ways, from picking out a casket to choosing a lipstick for the funeral. It even returns to different interactions with "the portal," though in ways that for me (and for the narrator, I think) had greater heft and resonance than any of the tweets or whatever that came before, at least in my opinion. The tone shifts and grows and folds back in on itself and expands further.

All of which reminded me, in a sorta sidebar, that people tweet and post about grief all the time. We share photos of loved ones on Instagram and publicly mourn our relatives on Facebook—I know I've done it and found it truly meaningful. What do you think, how good or bad is the web as a place to grieve?

Corin: I don't know if we can classify the web as being either a "good" or "bad" place to grieve, because grieving is one of those things in life that, despite being something that everyone feels at some point in their life, is impossible to define and takes on different forms for each person. For some people, posting about their loss and pain online is their way of processing their grief, and I'm sure the likes and comments provide a certain amount of comfort. For other people, the thought of sharing their grief on the same platforms where people are sharing flat-Earth conspiracies and funny animal videos is probably blasphemous, and they prefer to keep their mourning offline. Rather than focusing on what is right or wrong, I think we are better served to remember that grief is a motherfucker and we are all doing our best.

Rosecrans: Another sidebar question: Books told in fragments are your favorite thing, your least favorite thing, or something in the middle?

Corin: I think books told in fragments is kind of like improv comedy: When it's done well it's fantastic and feels original and fresh. If it's done poorly, I just want to die.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

A woman who has recently been elevated to prominence for her social media posts travels around the world to meet her adoring fans. She is overwhelmed by navigating the new language and etiquette of what she terms "the portal," where she grapples with an unshakable conviction that a vast chorus of voices is now dictating her thoughts. "Are we in hell?" the people of the portal ask themselves. "Are we all just going to keep doing this until we die?" Suddenly, two texts from her mother pierce the fray: "Something has gone wrong," and "How soon can you get here?" As real life and its stakes collide with the increasingly absurd antics of the portal, the woman confronts a world that seems to contain both an abundance of proof that there is goodness, empathy, and justice in the universe, and a deluge of evidence to the contrary.

Book description excerpted from publisher's summary and edited for length.

Rosecrans: I can't say improv comedy is something I've missed during the pandemic.

Corin: So… middle?

Rosecrans: Let me try a rephrase, especially since you're a librarian. Does a book told in fragments feel particularly of the Twitter era?

Corin: I think so. Even though the fragments aren't said to be specifically from some sort of social media update, they could easily be. Maybe books written in 280-character chunks are the modern version of an epistolary novel? Pamela used letters, Microserfs used diary entries on a computer, Where'd You Go, Bernadette used emails. As more of our collective communication is done in smaller fragments, maybe so will our literature.

Rosecrans: There's a lot to unpack there that we don't have room for. (Commentariat, je t'aime.) How much is this book going to stick with you, do you think?

Corin: I noticed after finishing it, I was more aware of my relationship with the internet and what I was consuming online. If no one is talking about the bigger things of life—grief and family and love—then what are we talking about? And why am I voluntarily making myself witness to these conversations? Only this morning, I found myself clicking to read the comments section on a local news story that I knew was going to be just a smoldering garbage fire and, surprise surprise, it was awful.

Rosecrans: Wait, what was it about?

Corin: It was some article about masking laws or people protesting them. Truly, after over a year of these articles I think everyone knows what the comments section will look like but… I still had to look? I just had to see if people were still being pretty terrible to each other online. Spoiler: They are!

But I also didn't want to miss the awful, I felt some need to see it so then I could say that I saw it, that I am knowledgeable of what is going on out there, which I think is an impulse that was captured pretty well with the narrator's own behavior. I can see myself rereading this book when I need a reminder that just because I can look at it online, doesn't mean I should.

Rosecrans: So, once and for all, can a dog be twins?

Corin: OK, I don't know if it's an occupational hazard as a reference librarian or just my own particular form of neuroticism, but whenever I run across a question like this, I have to start looking for an answer, otherwise I start getting itchy and irritable.

Yes, I am a blast to have at parties.

So, the answer depends on the type of twin you are looking for. Technically, since dogs give birth in litters, all of the puppies of the litter can be considered to be dizygotic (fraternal) siblings. If there is a litter of two puppies, those two puppies are fraternal twins.

Apparently, identical (monozygotic) twins are extremely rare in the animal world. Outside of humans, only the nine-banded armadillo is known to have genetically identical embryos consistently (and, in fact, routinely give birth to identical quadruplets every time, showing once again that nature is just weird, man). There have been a few cases of monozygotic siblings born to cows, horses, and other livestock, but usually they are born as conjoined or two-headed animals and rarely survive into adulthood, and generally bum people out.

That said, there was a confirmed case of identical wolfhound puppies that were born in South Africa in 2016. The vet had to perform a Caesarean section and saw that two puppies were encompassed in a single placenta, a mark of monozygotic siblings. He followed up with genetic testing on the puppies, which showed that they did, in fact, have identical DNA. It was the first identified pair of dog identical twins, and the birth was written up in the journal Reproduction in Domestic Animals. There have probably been other identical twin puppies born over the years, but since dogs aren't in the habit of getting regular sonograms, and 23andMe has yet to develop canine services, they probably happened unnoticed.

BTW, the puppies were named Cullen and Romulus and are extremely fucking cute. If you are a warm-blooded human and not a robot, you probably want to see pictures of them, which you can in this BBC article, that also includes the following unintentionally hilarious sentence: "We are so lucky that this bitch ended up having a C-section."

Rosecrans: I am so, so glad we had a reference librarian as this week's Activity Leader. Corin, thank you! Everyone else, we'll see you in the comments, then back here again next week for the first half of Detransition, Baby. I'm sure we'll have nothing to talk about.

Thank you to our Sustaining Members for making this event possible. Please take a moment to find out why TMN and the ToB depend on your support, and consider becoming a Sustaining Member or making a one-time donation. Remember: Sustaining Members get 50 percent off all ToB merch at the TMN Store, including Camp 2021 designs!

The Camp ToB 2021 Calendar

- June 2: No One Is Talking About This through part one

- June 9: No One Is Talking About This to the end

- June 16: Detransition, Baby through chapter four

- June 23: Detransition, Baby to the end

- June 30: Klara and the Sun through part three

- July 7: VACATION

- July 14: Klara and the Sun to the end

- July 21: Whereabouts through "At the Cash Register"

- July 28: Whereabouts to the end

- Aug. 4: Peaces through chapter eight

- Aug. 11: Peaces to the end

- Aug. 18: Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch through page 137

- Aug. 25: Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch to the end

- Sept. 1: Announce summer champion

You can find all our summer titles at our Camp ToB 2021 Bookshop list.